Directors Fortnight Cannes 2000 Winner Best Feature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dsrp Equateur 2

1 République Démocratique du Congo PROVINCE DE L’EQUATEUR PAIX – JUSTICE – TRAVAIL 2 « Juin 2006 » TABLE DES MATIERES Liste des tableaux INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................6 CONTEXTE ET JUSTIFICATION........................................................................................6 CHAP. I : CONTEXTE ET PROCESSUS DE L’ELABORATION DU DSRP PROVINCIAL...............................................................................................................8 1.1. CONTEXTE POLITIQUE ET ECONOMIQUE .............................................................8 1.2 PROCESSUS DE L’ELABORATION DU DSRP..................................................8 VOLONTE POLITIQUE DU GOUVERNEMENT ET DE L’EXECUTIF PROVINCIAL ....................8 1.3 MISE EN PLACE DU COMITE PROVINCIAL DE LUTTE CONTRE LA PAUVRETE .........9 1.4 ELABORATION DE LA MONOGRAPHIE PROVINCIALE .......................................... 10 1.5 CONSULTATIONS PARTICIPATIVES SUR LA PAUVRETE AUPRES DES COMMUNAUTES DE BASE ..................................................................................................................... 10 1.6 ENQUETE SUR LA PERCEPTION DE LA PAUVRETE............................................... 11 1.7 ENQUETE SUR LES CONDITIONS DE VIE DES MENAGES, L’EMPLOI ET LE SECTEUR INFORMEL .................................................................................................................. 11 1.8 REDACTION ET VALIDATION DU DSRP PROVINCIAL ....................................... -

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons Or Profiteers?

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons or Profiteers? By Jo-Ansie van Wyk Occasional Paper Series: Volume 2, Number 1, 2007 The Occasional Paper Series is published by The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). ACCORD is a non-governmental, non-aligned conflict resolution organisation based in Durban, South Africa. ACCORD is constituted as an education trust. Views expressed in this Occasional Paper are not necessarily those of ACCORD. While every attempt is made to ensure that the information published here is accurate, no responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage that may arise out of the reliance of any person upon any of the information this Occassional Paper contains. Copyright © ACCORD 2007 All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISSN 1608-3954 Unsolicited manuscripts may be submitted to: The Editor, Occasional Paper Series, c/o ACCORD, Private Bag X018, Umhlanga Rocks 4320, Durban, South Africa or email: [email protected] Manuscripts should be about 10 000 words in length. All references must be included. Abstract It is easy to experience a sense of déjà vu when analysing political lead- ership in Africa. The perception is that African leaders rule failed states that have acquired tags such as “corruptocracies”, “chaosocracies” or “terrorocracies”. Perspectives on political leadership in Africa vary from the “criminalisation” of the state to political leadership as “dispensing patrimony”, the “recycling” of elites and the use of state power and resources to consolidate political and economic power. -

The Political Role of the Ethnic Factor Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Political Role of the Ethnic Factor around Elections in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Hubert Kabungulu Ngoy-Kangoy Abstract This paper analyses the role of the ethnic factor in political choices in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and its impact on democratisa- tion and the implementation of the practice of good governance. This is done by focusing especially on the presidential and legislative elections of 1960 and 2006. The Congolese electorate is known for its ambiguous and paradoxical behaviour. At all times, ethnicity seems to play a determining role in the * Hubert Kabungulu Ngoy-Kangoy is a research fellow at the Centre for Management of Peace, Defence and Security at the University of Kinshasa, where he is a Ph.D. candidate in Conflict Resolution. The key areas of his research are good governance, human security and conflict prevention and resolution in the SADC and Great Lakes regions. He has written a number of articles and publications, including La transition démocratique au Zaïre (1995), L’insécurité à Kinshasa (2004), a joint work, The Many Faces of Human Security (2005), Parties and Political Transition in the Democratic Republic of Congo (2006), originally in French. He has been a researcher-consultant at the United Nations Information Centre in Kinshasa, the Centre for Defence Studies at the University of Zimbabwe, the Institute of Security Studies, Pretoria, the Electoral Institute of Southern Africa, the Southern African Institute of International Affairs and the Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria. The article was translated from French by Dr Marcellin Vidjennagni Zounmenou. 219 Hubert Kabungulu Ngoy-Kangoy choice of leaders and so the politicians, entrusted with leadership, keep on exploiting the same ethnicity for money. -

Questions Concerning the Situation in the Republic of the Congo (Leopoldville)

QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE SITUATION IN THE CONGO (LEOPOLDVILLE) 57 QUESTIONS RELATING TO Guatemala, Haiti, Iran, Japan, Laos, Mexico, FUTURE OF NETHERLANDS Nigeria, Panama, Somalia, Togo, Turkey, Upper NEW GUINEA (WEST IRIAN) Volta, Uruguay, Venezuela. A/4915. Letter of 7 October 1961 from Permanent Liberia did not participate in the voting. Representative of Netherlands circulating memo- A/L.371. Cameroun, Central African Republic, Chad, randum of Netherlands delegation on future and Congo (Brazzaville), Dahomey, Gabon, Ivory development of Netherlands New Guinea. Coast, Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, A/4944. Note verbale of 27 October 1961 from Per- Togo, Upper Volta: amendment to 9-power draft manent Mission of Indonesia circulating statement resolution, A/L.367/Rev.1. made on 24 October 1961 by Foreign Minister of A/L.368. Cameroun, Central African Republic, Chad, Indonesia. Congo (Brazzaville), Dahomey, Gabon, Ivory A/4954. Letter of 2 November 1961 from Permanent Coast, Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Representative of Netherlands transmitting memo- Togo, Upper Volta: draft resolution. Text, as randum on status and future of Netherlands New amended by vote on preamble, was not adopted Guinea. by Assembly, having failed to obtain required two- A/L.354 and Rev.1, Rev.1/Corr.1. Netherlands: draft thirds majority vote on 27 November, meeting resolution. 1066. The vote, by roll-call was 53 to 41, with A/4959. Statement of financial implications of Nether- 9 abstentions, as follows: lands draft resolution, A/L.354. In favour: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, A/L.367 and Add.1-4; A/L.367/Rev.1. Bolivia, Congo Brazil, Cameroun, Canada, Central African Re- (Leopoldville), Guinea, India, Liberia, Mali, public, Chad, Chile, China, Colombia, Congo Nepal, Syria, United Arab Republic: draft reso- (Brazzaville), Costa Rica, Dahomey, Denmark, lution and revision. -

Unrevised Transcript of Evidence Taken Before the Select Committee On

Unrevised transcript of evidence taken before The Select Committee on Economic Affairs Inquiry on THE ECONOMIC IMPACT AND EFFECTIVENESS OF DEVELOPMENT AID Evidence Session No. 12. Heard in Public. Questions 399 - 459 TUESDAY 29 NOVEMBER 2011 3.40 pm Witnesses: Ms Michela Wrong USE OF THE TRANSCRIPT 1. This is an uncorrected transcript of evidence taken in public and webcast on www.parliamentlive.tv. 2. Any public use of, or reference to, the contents should make clear that neither Members nor witnesses have had the opportunity to correct the record. If in doubt as to the propriety of using the transcript, please contact the Clerk of the Committee. 3. Members and witnesses are asked to send corrections to the Clerk of the Committee within 7 days of receipt. 1 Members present Lord MacGregor of Pulham Market (Chairman) Lord Best Lord Forsyth of Drumlean Lord Hollick Lord Lawson of Blaby Lord Lipsey Lord Moonie Lord Shipley Lord Smith of Clifton Lord Tugendhat ________________ Examination of Witness Ms Michela Wrong, Author of It’s Our Turn to Eat Q399 The Chairman: Welcome to the Economic Affairs Committee. This is the 12th public hearing of our inquiry into the impact and effectiveness of development aid, and I have to say as a matter of form that copies are available of Members’ entries in the Register of Interests. Welcome back to the Committee, Ms Wrong, and I would very much like to thank you for your written submission to us which was very eloquent, very well expressed and extremely interesting. Michela Wrong: Thank you. -

Loyalist Monitoring, and the Sorcery Masonic Lodge∗

Chapter 4 of Inside Autocracy Expanding the Governing Coalition: \Unite and Rule", Loyalist Monitoring, and the Sorcery Masonic Lodge∗ Brett L. Cartery November 4, 2012 Abstract Scholars have long believed autocrats \divide and rule" their elite; divided elites, the argu- ment goes, are unable to conspire against the autocrat. Yet historical evidence suggests some autocrats do precisely the opposite. This chapter's theoretical model argues an autocrat may create a compulsory elite social club if his inner circle is sufficiently large. Frequent interaction between the inner circle and less trustworthy elite enables the loyalists to learn about { and thus prevent { nascent conspiracies. By reducing the probability of coups d'´etat from less trustwor- thy elites, \unite and rule" monitoring enable the autocrat to expand his governing coalition. Sassou Nguesso's compulsory elite social club takes the form of a Freemasonry lodge, created just before he seized power in 1997. After providing statistical evidence that high level appoint- ment is the best predictor of lodge membership, the chapter employs a matching estimator to establish that lodge membership causes elites to engage in less anti-regime behavior. ∗This research was made possible by grants from the National Science Foundation, United States Institute of Peace, Social Science Research Council, Smith Richardson Foundation, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, and Institute for Quantitative Social Science. Thanks to Robert Bates, John Clark, Wonbin Kang, Steve Levitsky, James Robinson, and Yuri Zhukov for helpful comments and encouragement, as well as seminar participants at Harvard University and University of Wisconsin-Madison. My greatest debts are to several Congolese friends, who made this research possible and must remain anonymous. -

Cyrano De Bergerac

7 November to 16 December 2018 www.frenchfilmfestival.org.uk A TOUCH OF STYLE Nestled in the heart of Edinburgh and only two minutes from Princes Street, the ibis Styles St Andrew Square is an ideal base to tease tales from this mysterious city. Whether you're here to have a date with History, browse some Burns or have an intimate affair with a single malt, this hotel could not be better placed to fulfil your dreams. Not only that but breakfast and WIFI are included. The bedrooms are all uniquely designed and individual. 19 ST ANDREW SQUARE, EDINBURGH EH2 1AU TEL (+44) 131 292 0200 I FAX (+44) 131 292 0210 GENERAL INFORMATION [email protected] welcome BIENVENUE and welcome to the 26th Documentary selection features INDEX Edition of the French Film Festival UK five strong contenders – take your which every November and December partners for The Grand Ball; find out FILMS AT A GLANCE 5 –9 brings you the best of Francophone about the secrets of a master chef in cinema from France, Belgium, The Quest of Alain Ducasse; raise a PANORAMA HORIZONS 10 – 23 Switzerland, Quebec and French- glass to Wine Calling; join student speaking African territories. nurses for Nicolas Philbert’s Each DISCOVERY HORIZONS 24 – 28 For the first time this year the and Every Moment and uncover the DOCUMENTARY 29 – 31 Festival has established informal links daily life of a Parisian film school in The Graduation. with the Festival International du Film CROSSING BORDERS 33 / 34 Francophone in Namur in Belgium, Classics embrace master film-maker with whom we share titles and ideals. -

Programme Festival Cinémas D

2 Le 8ème FestivalEDITO entrecroise innovations, découvertes, et fidélité aux artistes déjà rencontrés, présente 15 longs métrages, environ 20 films courts,originaires de onze pays d’Afrique et des Caraïbes, avec un focus sur le Maroc (7 cinéastes). La fidélité aux fondateurs du cinéma d’Afrique c’est d’abord un hommage à des amis disparus : Sotigui Kouyaté, l’immense comédien, le conteur magique, Samba Félix Ndiaye, le documentariste si sensible et incisif, parti il y a juste un an, auquel nous associons un autre ami sénégalais, Mahama Johnson Traoré. Parmi les réalisateurs programmés, neuf l’avaient déjà été: Mahamat Saleh Haroun dont le film couronné à Cannes, sera la sixième oeuvre présentée à Apt, Raoul Peck, qui nous fait l’honneur, comme Faouzi Bensaïdi, d’une leçon de cinéma, Daoud Aoulad Syad, Brahim Fritah, Mohamed Zran, Dani Kouyaté, Malek Bensmaïl… Ce Festival sera aussi marqué par la découverte de nouveaux talents. Onze cinéastes présentent ici l’un de leurs premiers films, la plupart n’ayant pas encore réalisé un long métrage, Munir Abbar, El Mehdi Azzam, Nadia Chouieb, Alassane Diago, Dalila Ennadre, Dieudo Hamadi, Amal Kateb, Sani Magori, Lionel Meta, Othman Naciri, Zelalem Waldemariam… D’autres initiatives illustrent cette démarche : la soirée de la Fondation Blachère autour de Breeze Yoko et de vidéastes sud africains, la présentation de 11 films (de 2’) du projet Footsak, la présidence du jury par une toute jeune cinéaste sénégalaise, Angèle Diabang, le débat sur l’émergence d’une nouvelle génération de cinéastes et sa formation… Cette multiplicité de films couvre des sujets essentiels : le racisme, de la Vénus noire de Abdellatif Kechiche au regard colonial (avec des films d’archives d’il y a un siècle), les indépendances, l’émigration, la mondialisation… Et puis, tout naturellement, la vie, avec ses aventures, ses rencontres, ses tristesses, ses joies, ses imaginaires, l’énergie que chacun y trouve, est notre sujet à tous. -

Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba PDF Book

DEATH IN THE CONGO: MURDERING PATRICE LUMUMBA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Emmanuel Gerard | 252 pages | 10 Feb 2015 | HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9780674725270 | English | Cambridge, Mass, United States Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba PDF Book Gordon rated it it was ok Jun 13, This feud paved the way for the takeover by Congolese army chief Colonel Mobutu Sese Seko, who placed Patrice Lumumba under house arrest, guarded by his troops and the United Nations troops. I organised it. Wilson Omali Yeshitela. During an address by Ambassador Stevenson before the Security Council, a demonstration led by American blacks began in the visitors gallery. The Assassination of Lumumba illustrated ed. Sort order. This failed when Lumumba flatly refused the position of prime minister in a Kasa-Vubu government. It is suspected to have planned an assassination as disclosed by a source in the book, Death in the Congo , written by Emmanuel Gerard and published in If you wish to know more about the life story, legacy, or even philosophies of Lumumba, we suggest you engage in further reading as that will be beyond the scope of this article. As a result of strong pressure from delegates upset by Lumumba's trial, he was released and allowed to attend the Brussels conference. Paulrus rated it really liked it Jun 15, Time magazine characterized his speech as a 'venomous attack'. He was the leader of the largest political party in the country [Mouvement National Congolais], but one that never controlled more than twenty-five percent of the electorate on its own. As Madeleine G. -

Reporting on the Independence of the Belgian Congo: Mwissa Camus, the Dean of Congolese Journalists

African Journalism Studies ISSN: 2374-3670 (Print) 2374-3689 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/recq21 Reporting on the Independence of the Belgian Congo: Mwissa Camus, the Dean of Congolese Journalists Marie Fierens To cite this article: Marie Fierens (2016) Reporting on the Independence of the Belgian Congo: Mwissa Camus, the Dean of Congolese Journalists, African Journalism Studies, 37:1, 81-99, DOI: 10.1080/23743670.2015.1084584 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2015.1084584 Published online: 09 Mar 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=recq21 Download by: [Archives & Bibliothèques de l'ULB] Date: 10 March 2016, At: 00:16 REPORTING ON THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE BELGIAN CONGO: MWISSA CAMUS, THE DEAN OF CONGOLESE JOURNALISTS Marie Fierens Centre de recherche en sciences de l'information et de la communication (ReSIC) Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) [email protected] ABSTRACT Many individuals were involved in the Belgian Congo’s attainment of independence. Born in 1931, Mwissa Camus, the dean of Congolese journalists, is one of them. Even though he was opposed to this idea and struggled to maintain his status as member of a certain ‘elite’, his career sheds light on the advancement of his country towards independence in June 1960. By following his professional career in the years preceding independence, we can see how his development illuminates the emergence of journalism in the Congo, the social position of Congolese journalists, and the ambivalence of their position towards the emancipation process. -

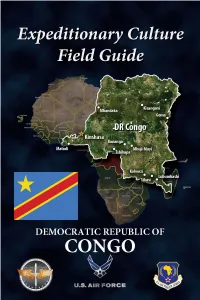

ECFG-DRC-2020R.Pdf

ECFG About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally t complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The he fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. Democratic Republicof The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), focusing on unique cultural features of the DRC’s society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN © Siegfried Modola). the For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact Congo AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

Front Matter.P65

Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files CONGO 1960–January 1963 INTERNAL AFFAIRS Decimal Numbers 755A, 770G, 855A, 870G, 955A, and 970G and FOREIGN AFFAIRS Decimal Numbers 655A, 670G, 611.55A, and 611.70G Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide Compiled by Martin Schipper A UPA Collection from 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Congo, 1960–January 1963 [microform] : internal affairs and foreign affairs / [project coordinator, Robert E. Lester]. microfilm reels ; 35 mm. Accompanied by a printed guide, compiled by Martin Schipper, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Congo, 1960–January 1963. “The documents reproduced in this publication are among the records of the U.S. Department of State in the custody of the National Archives of the United States.” ISBN 1-55655-809-0 1. Congo (Democratic Republic)—History—Civil War, 1960–1965—Sources. 2. Congo (Democratic Republic)—Politics and government—1960–1997—Sources. 3. Congo (Democratic Republic)—Foreign relations—1960–1997—Sources. 4. United States. Dept. of State—Archives. I. Title: Confidential US State Department central files. Congo, 1960–January 1963. II. Lester, Robert. III. Schipper, Martin Paul. IV. United States. Dept. of State. V. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. VI. University Publications of America (Firm) VII. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Congo, 1960–January 1963. DT658.22 967.5103’1—dc21 2001045336 CIP The documents reproduced in this publication are among the records of the U.S.