Loyalist Monitoring, and the Sorcery Masonic Lodge∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directors Fortnight Cannes 2000 Winner Best Feature

DIRECTORS WINNER FORTNIGHT BEST FEATURE CANNES PAN-AFRICAN FILM 2000 FESTIVAL L.A. A FILM BY RAOUL PECK A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE JACQUES BIDOU presents A FILM BY RAOUL PECK Patrice Lumumba Eriq Ebouaney Joseph Mobutu Alex Descas Maurice Mpolo Théophile Moussa Sowié Joseph Kasa Vubu Maka Kotto Godefroid Munungo Dieudonné Kabongo Moïse Tshombe Pascal Nzonzi Walter J. Ganshof Van der Meersch André Debaar Joseph Okito Cheik Doukouré Thomas Kanza Oumar Diop Makena Pauline Lumumba Mariam Kaba General Emile Janssens Rudi Delhem Director Raoul Peck Screenplay Raoul Peck Pascal Bonitzer Music Jean-Claude Petit Executive Producer Jacques Bidou Production Manager Patrick Meunier Marianne Dumoulin Director of Photography Bernard Lutic 1st Assistant Director Jacques Cluzard Casting Sylvie Brocheré Artistic Director Denis Renault Art DIrector André Fonsny Costumes Charlotte David Editor Jacques Comets Sound Mixer Jean-Pierre Laforce Filmed in Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Belgium A French/Belgian/Haitian/German co-production, 2000 In French with English subtitles 35mm • Color • Dolby Stereo SRD • 1:1.85 • 3144 meters Running time: 115 mins A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE 247 CENTRE ST • 2ND FL • NEW YORK • NY 10013 www.zeitgeistfilm.com • [email protected] (212) 274-1989 • FAX (212) 274-1644 At the Berlin Conference of 1885, Europe divided up the African continent. The Congo became the personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium. On June 30, 1960, a young self-taught nationalist, Patrice Lumumba, became, at age 36, the first head of government of the new independent state. He would last two months in office. This is a true story. SYNOPSIS LUMUMBA is a gripping political thriller which tells the story of the legendary African leader Patrice Emery Lumumba. -

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons Or Profiteers?

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons or Profiteers? By Jo-Ansie van Wyk Occasional Paper Series: Volume 2, Number 1, 2007 The Occasional Paper Series is published by The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). ACCORD is a non-governmental, non-aligned conflict resolution organisation based in Durban, South Africa. ACCORD is constituted as an education trust. Views expressed in this Occasional Paper are not necessarily those of ACCORD. While every attempt is made to ensure that the information published here is accurate, no responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage that may arise out of the reliance of any person upon any of the information this Occassional Paper contains. Copyright © ACCORD 2007 All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISSN 1608-3954 Unsolicited manuscripts may be submitted to: The Editor, Occasional Paper Series, c/o ACCORD, Private Bag X018, Umhlanga Rocks 4320, Durban, South Africa or email: [email protected] Manuscripts should be about 10 000 words in length. All references must be included. Abstract It is easy to experience a sense of déjà vu when analysing political lead- ership in Africa. The perception is that African leaders rule failed states that have acquired tags such as “corruptocracies”, “chaosocracies” or “terrorocracies”. Perspectives on political leadership in Africa vary from the “criminalisation” of the state to political leadership as “dispensing patrimony”, the “recycling” of elites and the use of state power and resources to consolidate political and economic power. -

Kitona Operations: Rwanda's Gamble to Capture Kinshasa and The

Courtesy of Author Courtesy of Author of Courtesy Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers during 1998 Congo war and insurgency Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers guard refugees streaming toward collection point near Rwerere during Rwanda insurgency, 1998 The Kitona Operation RWANDA’S GAMBLE TO CAPTURE KINSHASA AND THE MIsrEADING OF An “ALLY” By JAMES STEJSKAL One who is not acquainted with the designs of his neighbors should not enter into alliances with them. —SUN TZU James Stejskal is a Consultant on International Political and Security Affairs and a Military Historian. He was present at the U.S. Embassy in Kigali, Rwanda, from 1997 to 2000, and witnessed the events of the Second Congo War. He is a retired Foreign Service Officer (Political Officer) and retired from the U.S. Army as a Special Forces Warrant Officer in 1996. He is currently working as a Consulting Historian for the Namib Battlefield Heritage Project. ndupress.ndu.edu issue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 / JFQ 99 RECALL | The Kitona Operation n early August 1998, a white Boeing remain hurdles that must be confronted by Uganda, DRC in 1998 remained a safe haven 727 commercial airliner touched down U.S. planners and decisionmakers when for rebels who represented a threat to their unannounced and without warning considering military operations in today’s respective nations. Angola had shared this at the Kitona military airbase in Africa. Rwanda’s foray into DRC in 1998 also concern in 1996, and its dominant security I illustrates the consequences of a failure to imperative remained an ongoing civil war the southwestern Bas Congo region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

New Nations in Africa

3 New Nations in Africa MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES REVOLUTION After World War II, Today, many of those • Negritude • Ahmed Ben African leaders threw off independent countries are movement Bella colonial rule and created engaged in building political •Kwame •Mobutu independent countries. and economic stability. Nkrumah Sese Seko • Jomo Kenyatta SETTING THE STAGE Throughout the first half of the 20th century, Africa resembled little more than a European outpost. As you recall, the nations of Europe had marched in during the late 1800s and colonized much of the conti- nent. Like the diverse groups living in Asia, however, the many different peoples of Africa were unwilling to return to colonial domination after World War II. And so, in the decades following the great global conflict, they, too, won their inde- pendence from foreign rule and went to work building new nations. TAKING NOTES Achieving Independence Clarifying Use a chart to list an idea, an event, or a The African push for independence actually began in the decades before World War leader important to that II. French-speaking Africans and West Indians began to express their growing sense country’s history. of black consciousness and pride in traditional Africa. They formed the Negritude movement, a movement to celebrate African culture, heritage, and values. When World War II erupted, African soldiers fought alongside Europeans to Ghana “defend freedom.” This experience made them unwilling to accept colonial dom- Kenya ination when they returned home. The war had changed the thinking of Zaire Europeans too. Many began to question the cost, as well as the morality, of main- taining colonies abroad. -

"Where Elephants Fight the Grass Is Trampled"

Jason Stearns. Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa. New York: PublicAffairs, 2012. 417 pp. $16.99, paper, ISBN 978-1-61039-107-8. Reviewed by Matthew G. Stanard Published on H-Empire (June, 2012) Commissioned by Charles V. Reed (Elizabeth City State University) For many who grew up during the Cold War, the African National Congress on a path toward the competition between capitalism and commu‐ one-party dominance. Japanese economic growth nism seemed to determine the unfolding of histo‐ was followed by a crash and the so-called lost ry. Then 1989 happened, and communism col‐ decade. India and Pakistan both tested nuclear lapsed spectacularly. Francis Fukuyama famously weapons. Multiple terrorist strikes in and outside proclaimed the end of history, that is, the end of the United States presaged the 2001 attacks. ideological competition and the triumph of West‐ Considering all this, it is unsurprising that ern liberal democracy.[1] Of course history did anyone who lived through the 1990s had trouble not end, ideological battles continued, and the keeping track of the multitude of developments decade that followed witnessed a dizzying array also unfolding in Rwanda and Zaire (later rebap‐ of complex developments. Saddam Hussein’s Iraq tized the Democratic Republic of the Congo). A invaded Kuwait and was expelled. Mengistu Haile century earlier, during the 1890s, news about Mariam’s regime collapsed in Ethiopia and Eritrea atrocities in the Congo were hard to come by and gained its independence, which led to an extraor‐ it took dedicated efforts by individuals like E. -

Africa's Soft Power : Philosophies, Political Values, Foreign Policies and Cultural Exports / Oluwaseun Tella

“This seven-chapter book is a powerful testimonial to consummate African scholarship. Its analysis is rigorous, insightful, lucid and authoritative, providing fresh perspectives on selected uniquely African philosophies, and the potential ities, deployment and limitations of soft power in Africa’s international relations. The author rigorously Africanises the concept, broadening its analytic scope from its biased Western methodology, thus brilliantly fulfilling that great African pro verb made famous by the inimitable Chinua Achebe: ‘that until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter’. This is truly an intellectual tour de force.” W. Alade Fawole, Professor of International Relations, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. “This book addresses an important tool in the arsenal of foreign policy from an African perspective. African states have significant soft power capacities, although soft power is not always appreciated as a lever of influence, or fully integrated into countries’ foreign policy strategies. Tella takes Nye’s original concept and Africanises it, discussing Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa via their respective philosophies of Pharaonism, Harambee, Omolúwàbí and Ubuntu. This study is a critical contribution to the literature on African foreign policies and how to use soft power to greater effect in building African agency on the global stage.” Elizabeth Sidiropoulos, Chief Executive, South African Institute of International Affairs, Johannesburg, South Africa. “Soft power is seldom associated with African states, given decades bedevilled by coup d’états, brazen dictatorships and misrule. This ground-breaking book is certainly a tour de force in conceptualising soft power in the African context. -

Patrice Émery Lumumba

Swarthmore College Works French & Francophone Studies Faculty Works French & Francophone Studies 2008 Patrice Émery Lumumba Carina Yervasi Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-french Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Carina Yervasi. (2008). "Patrice Émery Lumumba". A Historical Companion To Postcolonial Literatures: Continental Europe And Its Empires. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-french/46 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in French & Francophone Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Patrice Émery Lumumba 37 Patrice Émery Lumumba Patrice Émery Lumumba (1925–61), a Congolese leader of the nationalist independence movement against Belgian colonialism and co-founder of the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC) in 1958, was the first Prime Minister of what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo from June 1960 until September 1960, when he was removed from office by a confluence of forces under the direction of President Joseph Kasavubu, Colonel Joseph Désiré Mobutu, and Belgian and American officials. Lumumba was born in Onalua in the Katako-Kombe district of Sankuru in the Kasai province of the Belgian Congo and educated by Protestant missionaries. He was registered as an évolué and worked as a postal clerk and as a charismatic salesman, an image made famous first in Aimé Césaire’s play Une Saison au Congo (1967) and then in Raoul Peck’s biographical film Lumumba (2000). He became active in the independence movements in the mid-1950s and began a career as a journalist and writer, editing a Congolese postal workers’ newspaper L’Écho, and writing for La Voix du Congolais, La Croix du Congo and the Belgium-based, L’Afrique et le Monde. -

List of Dictators Number Name Country Student's Name

List of Dictators Number Name Country Student’s Name 1 Adolf Hitler Germany 2 Josef Stalin USSR 3 Benito Mussolini Italy 4 Mao Zedong China 5 Ho Chi Minh North Vietnam 6 Francisco Franco Spain 7 Muhammad Reza Pahlavi Iran 8 Vladimir Lenin USSR 9 Saddam Hussein Iraq/ Iraq 10 Kim Il Sung North Korea 11 Josip Broz Tito Yugoslavia 12 Deng Xiaoping China 13 Augusto Pinochet Chile 14 Muammar Gaddafi Libya 15 Kim Jong Il North Korea 16 Park Chung Hee South Korea 17 Enver Hoxha Albania 18 Ferdinand Marcos Philippines 19 Fidel Castro Cuba 20 Janos Kadar Hungary 21 Haile Selassie Ethiopia 22 Pol Pot Cambodia 23 Antonio de Oliveira Salazar Portugal 24 Fulgencio Batista Cuba 25 Juan Peron Argentina 26 Francois Duvalier Haiti 27 Charles Taylor Liberia 28 Anwar Sadat Egypt 29 Omar al-Bashir Sudan 30 Meles Zenawi Ethiopia 31 José Efraín Ríos Montt Guatemala 32 Alfredo Stroessner Paraguay 33 Erich Honecker GDR 34 Maumoon Gayoom Maldives 35 Nikita Khruschev USSR 36 Idi Amin Dada Uganda 37 Ruhollah Khomeini Iran 38 Mobutu Sese Seko Zaire 39 Francisco Macias Nguema Equatorial Guinea 40 Klement Gottwald Czechoslovakia 41 Alecksander Lukashenko Belarus 42 Saparmarut Niyazov Turkmenistan Teodoro Obiang Nguema 43 Equatorial Guinea Mbasogo 44 Hugo Chavez Venezuela 45 Tsar Nicholas Romanov II Russia 46 Hissène Habré Chad 47 Havez al-Assad Syria 48 Mengistu Haile Mariam Ethiopia 49 Slobodan Milosevic Yugoslavia 50 Manuel Noriega Panama 51 Robert Mugabé Zimbabwe 52 Islom Karimov Uzbekistan 53 Pervez Musharraf Pakistan 54 Etienne Gnassingbé Eyadéma Togo 55 Todor Zhivkov Bulgaria 56 Isaias Afewerki Eritrea Central African 57 Jean-Bédel Bokassa Republic 58 Józef Klemens Piłsudski Poland 59 Ali Abdullah Saleh Yemen 60 Samuel Kanyon Doe Liberia 61 Levon Ter-Petrosyan Armenia 62 Than Shwe Myanmar 63 Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq Pakistan 64 King Mswati III Swaziland 65 Sani Abacha Nigeria 66 Yong Shikai China 67 Wojciech Jaruzelski Poland . -

1 the Congo Crisis, 1960-1961

The Congo Crisis, 1960-1961: A Critical Oral History Conference Organized by: The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars’ Cold War International History Project and Africa Program Sponsored by: The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars September 23-24, 2004 Opening of Conference – September 23, 2004 CHRISTIAN OSTERMANN: Ladies and gentlemen I think we’ll get started even though we’re still expecting a few colleagues who haven’t arrived yet, but I think we should get started because we have quite an agenda for this meeting. Welcome all of you to the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars; my name is Christian Ostermann. I direct one of the programs here at the Woodrow Wilson Center, the Cold War International History Project. The Center is the United States’ official memorial to President Woodrow Wilson and it celebrates, commemorates Woodrow Wilson through a living memorial, that is, we bring scholars from around the world, about 150 each year to the Wilson center to do research and to write. In addition to hosting fellowship programs, the Center hosts 450 meetings each year on a broad array of topics related to international affairs. One of these meetings is taking place today, and it is a very special meeting, as I will explain in a few moments. This meeting is co-sponsored by the Center’s Cold War International History project and 1 the Center’s Africa Program, directed by former Congressman Howard Wolpe. He’s in Burundi as we speak here, but some of his staff will be joining us during the course of the day. -

Modern African Leaders

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 446 012 SO 032 175 AUTHOR Harris, Laurie Lanzen, Ed.; Abbey, CherieD., Ed. TITLE Biography Today: Profiles of People ofInterest to Young Readers. World Leaders Series: Modern AfricanLeaders. Volume 2. ISBN ISBN-0-7808-0015-X PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 223p. AVAILABLE FROM Omnigraphics, Inc., 615 Griswold, Detroit,MI 48226; Tel: 800-234-1340; Web site: http: / /www.omnigraphics.com /. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020)-- Reference Materials - General (130) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS African History; Biographies; DevelopingNations; Foreign Countries; *Individual Characteristics;Information Sources; Intermediate Grades; *Leaders; Readability;Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *Africans; *Biodata ABSTRACT This book provides biographical profilesof 16 leaders of modern Africa of interest to readersages 9 and above and was created to appeal to young readers in a format theycan enjoy reading and easily understand. Biographies were prepared afterextensive research, and this volume contains a name index, a general index, a place of birth index, anda birthday index. Each entry providesat least one picture of the individual profiled, and bold-faced rubrics lead thereader to information on birth, youth, early memories, education, firstjobs, marriage and family,career highlights, memorable experiences, hobbies,and honors and awards. All of the entries end with a list of highly accessiblesources designed to lead the student to further reading on the individual.African leaders featured in the book are: Mohammed Farah Aidid (Obituary)(1930?-1996); Idi Amin (1925?-); Hastings Kamuzu Banda (1898?-); HaileSelassie (1892-1975); Hassan II (1929-); Kenneth Kaunda (1924-); JomoKenyatta (1891?-1978); Winnie Mandela (1934-); Mobutu Sese Seko (1930-); RobertMugabe (1924-); Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972); Julius Kambarage Nyerere (1922-);Anwar Sadat (1918-1981); Jonas Savimbi (1934-); Leopold Sedar Senghor(1906-); and William V. -

Democratic Republic of Congo

APRIL 2016 Democratic Republic of Congo: A Review of 20 years of war Jordi Calvo Rufanges and Josep Maria Royo Aspa Escola de Cultura de Pau / Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO: A REVIEW OF 20 YEARS OF WAR April 2016 D.L.: B-16799-2010 ISSN: 2013-8032 Authors: Jordi Calvo Rufanges and Josep Maria Royo Aspa Support researchers: Elena Fernández Sandiumenge, Laura Marco Gamundi, Eira Massip Planas, María Villellas Ariño Project funded by the Agència Catalana de Cooperació al Desenvolupament INDEX 04 Executive summary 05 1. Introduction 06 2. Roots of the DRC conflict 09 3. Armed actors in the east of the DRC 15 4. Impacts of armamentism 19 5. Military spending 20 6. The political economy of the war 23 7. Current political and social situation 25 8. Gender dimension of the conflict 27 9. Conclusions 29 BIBLIOGRAPHY 34 ANNEX 34 Table 1: Exports of defense equipment from the EU to DRC (2001-2012) 35 Table 2: Arms sales identified in RDC (1995-2013) 36 Table 3: Transfer of small arms and light weapons from the EU to RDC (1995-2013) 37 Table 4: Transfers of small arms and light weapons to DRC (rest of the world) (2004-2013) 38 Table 5: Transfers of significant weapons in RDC and neighboring countries 39 Table 6: Internal arms deviations in the DRC conflict 40 Table 7. Identification of arms sources found in the conflict in DRC 41 Table 8: Exports of small arms and light weapons to Burundi (1995-2013) 42 Table 9: Exports of small arms and light weapons to Rwanda (1995 - 2013) LIST OF TABLES, GRAPHS AND MAPS 06 Map 2.1. -

Challenges of Nation Building in Africa and the Middle East Note the Uneasy Coexistence of the Modern World and the Traditional World in Africa

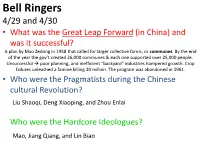

Bell Ringers 4/29 and 4/30 • What was the Great Leap Forward (in China) and was it successful? A plan by Mao Zedong in 1958 that called for larger collective farms, or communes. By the end of the year the gov’t created 26,000 communes & each one supported over 25,000 people. Unsuccessful poor planning, and inefficient “backyard” industries hampered growth. Crop failures unleashed a famine killing 20 million. The program was abandoned in 1961. • Who were the Pragmatists during the Chinese cultural Revolution? Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping, and Zhou Enlai Who were the Hardcore Ideologues? Mao, Jiang Qiang, and Lin Biao Ch. 17 Notes • Brinkmanship – A willingness to go to the brink, or edge, of war. *1953 – Eisenhower becomes U.S. President *He appoints John Foster Dulles as secretary of state. *Dulles says if the U.S.S.R. or its supporters attacked the U.S. or their interests, then the U.S. would retaliate immediately! • Détente – a policy of reducing Cold War tensions that was adopted by the U.S. during Richard Nixon’s presidency. This grew out of the philosophy known as realpolitik (realistic politics) aka. Dealing with other nations in a practical/flexible manner. • Francis Gary Powers & the U-2 incident (1960) *Soviets shot down a U-2 plane (CIA high altitude spy flight plane) over Soviet territory. Powers was captured and spent 19 months in prison. This event brings mistrust between the U.S. and Soviets. • Jospi Broz “Marshal” Tito & Yugoslavia Marshal= highest rank of Yugoslav People’s Army & only person to receive it.