Foreign-Language Comedy Production in the Third Reich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

Collisions with Hegel in Bertolt Brecht's Early Materialism DISSERTATIO

“Und das Geistige, das sehen Sie, das ist nichts.” Collisions with Hegel in Bertolt Brecht’s Early Materialism DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jesse C. Wood, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Germanic Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2012 Committee Members: John Davidson, Advisor Bernd Fischer Bernhard Malkmus Copyright by Jesse C. Wood 2012 Abstract Bertolt Brecht began an intense engagement with Marxism in 1928 that would permanently shape his own thought and creative production. Brecht himself maintained that important aspects resonating with Marxist theory had been central, if unwittingly so, to his earlier, pre-1928 works. A careful analysis of his early plays, poetry, prose, essays, and journal entries indeed reveals a unique form of materialism that entails essential components of the dialectical materialism he would later develop through his understanding of Marx; it also invites a similar retroactive application of other ideas that Brecht would only encounter in later readings, namely those of the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Initially a direct result of and component of his discovery of Marx, Brecht’s study of Hegel would last throughout the rest of his career, and the influence of Hegel has been explicitly traced in a number Brecht’s post-1928 works. While scholars have discovered proto-Marxist traces in his early work, the possibilities of the young Brecht’s affinities with the idealist philosopher have not been explored. Although ultimately an opposition between the idealist Hegel and the young Bürgerschreck Brecht is to be expected, one finds a surprising number of instances where the two men share an unlikely commonality of imagery. -

Foreign-Language Comedy Production in the Third Reich

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Theatre and Film Theatre and Film, Johnny Carson School of Spring 2001 Foreign-Language Comedy Production in the Third Reich William Grange University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/theatrefacpub Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Grange, William, "Foreign-Language Comedy Production in the Third Reich" (2001). Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Theatre and Film. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/theatrefacpub/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theatre and Film, Johnny Carson School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Theatre and Film by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Metamorphoses: A Journal of Literary Translation, vol. 9, no.1 (Spring 2001), pp. 179-196. FOREIGN-LANGUAGE COMEDY PRODUCTION IN THE THIRD REICH The two most frequently performed non-German comic ' on German-language stages from 1933 to 1944 were Carlo Goldoni (1 707-1793) and Oscar Wilde (1 854-1900), whose plays served the purposes of cultural transmission both by the theatre establishment and the political regime in power at the time. Goethe had seen Goldoni productions in Venice during his "Italian Journeys" between 1786 and 1788, and he reported that never in his life had he heard such "laughter and bellowing at a theatre."' It remajns unclear whether he meant laughing and bellowing on the part of audiences or the actors, but since his other remarks on the experience were fairly charitable, Goldoni's status rose a~cordingly.~Goethe himseIf enjoyed the exalted status of cultural arbiter with unimpeachable judgement, so Goldoni remained a solid fixture in German theatre reper- toires throughout the Third Reich. -

![Chapter 3 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3751/chapter-3-pdf-963751.webp)

Chapter 3 [PDF]

Chapter 3 Was There a Crisis of Opera?: The Kroll Opera's First Season, 1927-28 Beethoven's "Fidelio" inaugurated the Kroll Opera's first season on November 19, 1927. This was an appropriate choice for an institution which claimed to represent a new version of German culture - the product of Bildung in a republican context. This chapter will discuss the reception of this production in the context of the 1927-28 season. While most accounts of the Kroll Opera point to outraged reactions to the production's unusual aesthetics, I will argue that the problems the opera faced during its first season had less to do with aesthetics than with repertory choice. In the case of "Fidelio" itself, other factors were responsible for the controversy over the production, which was a deliberately pessimistic reading of the opera. I will go on to discuss the notion of a "crisis of opera", a prominent issue in the musical press during the mid-1920s. The Kroll had been created in order to renew German opera, but was the state of opera unhealthy in the first place? I argue that the "crisis" discussion was more optimistic than it has generally been portrayed by scholars. The amount of attention generated by the Kroll is evidence that opera was flourishing in Weimar Germany, and indeed was a crucial ingredient of civic culture, highly important to the project of reviving the ideals of the Bildungsbürgertum. 83 84 "Fidelio" in the Context of Republican Culture Why was "Fidelio" a representative German opera, particularly for the republic? This work has not always been viewed as political in nature. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Inhaltsverzeichnis Hinweis 9 Das Theater der Republik 11 Weimar und der Expressionismus 11 Die Väter und die Söhne 12 Die Zerstörung des Dramas 14 Die neuen Schauspieler 16 Die Provinz regt sich 18 Los von Berlin - Los von Reinhardt 20 Berlin und Wien 22 Zersetzter Expressionismus 24 Die große Veränderung 25 Brecht und Piscator 27 Wirklichkeit! Wirklichkeit! 30 Hitler an der Rampe 33 Der große Rest *35 Wieviel wert ist die Kritik? 37 Alte und neue Grundsätze 38 Selbstverständnis und Auseinandersetzungen 41 Die Macht und die Güte 44 *9*7 47 Rene Schickele, Hans im Schnakenloch 48 rb., Frankfurter Zeitung 48 Alfred Kerr, Der Tag, Berlin 50 Siegfried Jacobsohn, Die Schaubühne, Berlin 52 Georg Kaiser, Die Bürger von Calais 53 Kasimir Edschmid, Neue Zürcher Zeitung 54 Heinrich Simon, Frankfurter Zeitung 55 Alfred Polgar, Vossische Zeitung, Berlin 56 Georg Kaiser, Von Morgens bis Mitternachts 57 Richard Elchinger, Münchner Neueste Nachrichten 58 Richard Braungart, Münchener Zeitung 60 P. S., Frankfurter Zeitung 61 Richard Specht, Berliner Börsen-Courier 62 Oskar Kokoschka, Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen - Hiob - Der bren nende Dornbusch 63 Robert Breuer, Die Schaubühne, Berlin 64 Bernhard Diebold, Frankfurter Zeitung 66 Alfred Kerr, Der Tag, Berlin 69 Gerhart Hauptmann, Winterballade .. 72 Siegfried Jacobsohn, Die Schaubühne, Berlin 73 Julius Hart, Der Tag, Berlin 75 Emil Faktor, Berliner Börsen-Courier 77 1248 http://d-nb.info/207309981 Georg Kaiser, Die Koralle 79 Bernhard Diebold, Frankfurter Zeitung 79 Kasimir Edschmid, Vossische Zeitung, Berlin, und Neue Zürcher Zei tung 82 Emil Faktor, Berliner Börsen-Courier 83 Alfred Kerr, Der Tag, Berlin 84 Hanns Johst, Der Einsame, ein Menschenuntergang 86 Artur Kutscher, Berliner Tageblatt . -

Cultural Convergence the Dublin Gate Theatre, 1928–1960

Cultural Convergence The Dublin Gate Theatre, 1928–1960 Edited by Ondřej Pilný · Ruud van den Beuken · Ian R. Walsh Cultural Convergence “This well-organised volume makes a notable contribution to our understanding of Irish theatre studies and Irish modernist studies more broadly. The essays are written by a diverse range of leading scholars who outline the outstanding cultural importance of the Dublin Gate Theatre, both in terms of its national significance and in terms of its function as a hub of international engagement.” —Professor James Moran, University of Nottingham, UK “The consistently outstanding contributions to this illuminating and cohesive collection demonstrate that, for Gate Theatre founders Hilton Edwards and Micheál mac Liammóir and their collaborators, the limits of the imagination lay well beyond Ireland’s borders. Individually and collectively, the contribu- tors to this volume unravel the intricate connections, both personal and artistic, linking the theatre’s directors, designers, and practitioners to Britain, Europe, and beyond; they examine the development and staging of domestic plays written in either English or Irish; and they trace across national boundaries the complex textual and production history of foreign dramas performed in translation. In addition to examining a broad spectrum of intercultural and transnational influ- ences and perspectives, these frequently groundbreaking essays also reveal the extent to which the early Gate Theatre was a cosmopolitan, progressive, and inclusive space that recognized and valued women’s voices and queer forms of expression.” —Professor José Lanters, University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, USA “Cultural Convergence is a book for which we have been waiting, not just in Irish theatre history, but in Irish cultural studies more widely. -

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism By

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Anton Kaes, Chair Professor Martin Jay Professor Linda Williams Fall 2015 Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism © 2015 by Nicholas Walter Baer Abstract Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Anton Kaes, Chair This dissertation intervenes in the extensive literature within Cinema and Media Studies on the relationship between film and history. Challenging apparatus theory of the 1970s, which had presumed a basic uniformity and historical continuity in cinematic style and spectatorship, the ‘historical turn’ of recent decades has prompted greater attention to transformations in technology and modes of sensory perception and experience. In my view, while film scholarship has subsequently emphasized the historicity of moving images, from their conditions of production to their contexts of reception, it has all too often left the very concept of history underexamined and insufficiently historicized. In my project, I propose a more reflexive model of historiography—one that acknowledges shifts in conceptions of time and history—as well as an approach to studying film in conjunction with historical-philosophical concerns. My project stages this intervention through a close examination of the ‘crisis of historicism,’ which was widely diagnosed by German-speaking intellectuals in the interwar period. -

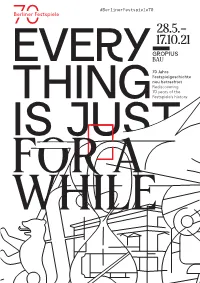

Everything Is Just for a While

#BerlinerFestspiele70 Berliner Festspiele70 28.5.– 17.10.21 GROPIUS BAU EVERY-70 Jahre Festspielgeschichte neu betrachtet Rediscovering 70 years of the THING Festspiele's history IS JUST FOR A WHILE Inhaltsverzeichnis / Table of contents INHALTS- VERZEICHNIS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Vorwort Preface 12 Eine Geschichte der Berliner Festspiele A History of the Berliner Festspiele 40 Videoinstallationen Video installations 54 Filme Films 88 Impressum Imprint Everything Is Just for a While EVERYTHING IS JUST FOR A WHILE 70 Jahre Festspielgeschichte neu betrachtet Rediscovering 70 years of the Festspiele's history Vorwort / Preface Labor und Experiment, Seismograf des Zeitgeist, Ausstellungsort und Debattierklub, Radical Art und Workshops für Jugendliche, Feuer werk und Sport, wochenlang afrikanische Kunst, Städteplanung A laboratory and an experiment, und Autor*innenförderung, Wissen a seismograph of the zeitgeist, an schaftskolleg und Festumzug mit exhibition space and a debating Wasserkorso und immer wieder society, radical art and workshops for Plattform der internationalen Kunst young people, fireworks and sporting szene – all das waren die Berliner events, weeks of African art, urban Festspiele in den vergangenen 70 planning and new writing, an Institute Jahren. Im Geburtstagsjahr zeigt of Advanced Studies and a celebra „Everything Is Just for a While” tory waterborne procession, a recur einen Zusammenschnitt aus rent platform for the international bis lang kaum bekannten Be wegt art scene – over the last 70 years the bildern, ein Spiegelkabinett der Berliner Festspiele have been all of Erin ner ungen. Die Videoinstalla these things. In their birthday year, tionen werden von einer Infowand “Everything Is Just for a While” pre gerahmt, die die Identität und die s ents a compilation of previously Geschichte der Berliner Festspiele littleknown film footage, a hall veranschaulichen. -

Filmklassiker Bel Ami (1939)

Filmklassiker Bel Ami (1939)...........................................................................................................................2 Der blaue Engel (1930)...............................................................................................................2 Ein blonder Traum (1932)...........................................................................................................3 Bomben auf Monte Carlo (1931).................................................................................................4 Die Brücke (1960) ......................................................................................................................4 Des Teufels General (1955) ........................................................................................................5 Das doppelte Lottchen (1950) .....................................................................................................6 3 Männer im Schnee (1956) ........................................................................................................6 Die Drei von der Tankstelle (1956) .............................................................................................7 Emil und die Detektive (1931) ....................................................................................................8 Die Feuerzangenbowle (1944).....................................................................................................8 Frauenarzt Dr. Prätorius (1950)...................................................................................................9 -

Documentary Theatre, the Avant-Garde, and the Politics of Form

“THE DESTINY OF WORDS”: DOCUMENTARY THEATRE, THE AVANT-GARDE, AND THE POLITICS OF FORM TIMOTHY YOUKER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Timothy Earl Youker All rights reserved ABSTRACT “The Destiny of Words”: Documentary Theatre, the Avant-Garde, and the Politics of Form Timothy Youker This dissertation reads examples of early and contemporary documentary theatre in order to show that, while documentary theatre is often presumed to be an essentially realist practice, its history, methods, and conceptual underpinnings are closely tied to the historical and contemporary avant-garde theatre. The dissertation begins by examining the works of the Viennese satirist and performer Karl Kraus and the German stage director Erwin Piscator in the 1920s. The second half moves on to contemporary artists Handspring Puppet Company, Ping Chong, and Charles L. Mee. Ultimately, in illustrating the documentary theatre’s close relationship with avant-gardism, this dissertation supports a broadened perspective on what documentary theatre can be and do and reframes discussion of the practice’s political efficacy by focusing on how documentaries enact ideological critiques through form and seek to reeducate the senses of audiences through pedagogies of reception. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS iii INTRODUCTION: Documents, Documentaries, and the Avant-Garde 1 Prologue: Some History 2 Some Definitions: Document—Documentary—Avant-Garde -

Tallafuss Diss Letzte Fassung Teil 1

University of Groningen Gerhart Hauptmann ist bei uns zu Hause Tallafuss, Petra IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2008 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Tallafuss, P. (2008). Gerhart Hauptmann ist bei uns zu Hause: zur Rezeption der sozialkritischen Dramen Gerhart Hauptmanns in der DDR. [s.n.]. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 06-10-2021 RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN „Gerhart Hauptmann ist bei uns zu Hause“ – Zur Rezeption der sozialkritischen Dramen Gerhart Hauptmanns in der DDR Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Letteren aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. -

Bertolt Brecht - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Bertolt Brecht - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Bertolt Brecht(10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956) Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht; was a German poet, playwright, and theatre director. An influential theatre practitioner of the 20th century, Brecht made equally significant contributions to dramaturgy and theatrical production, the latter particularly through the seismic impact of the tours undertaken by the Berliner Ensemble — the post-war theatre company operated by Brecht and his wife, long-time collaborator and actress Helene Weigel. <b>Life and Career</b> Bavaria (1898–1924) Bertolt Brecht was born in Augsburg, Bavaria, (about 50 miles (80 km) north- west of Munich) to a conventionally-devout Protestant mother and a Catholic father (who had been persuaded to have a Protestant wedding). His father worked for a paper mill, becoming its managing director in 1914. Thanks to his mother's influence, Brecht knew the Bible, a familiarity that would impact on his writing throughout his life. From her, too, came the "dangerous image of the self-denying woman" that recurs in his drama. Brecht's home life was comfortably middle class, despite what his occasional attempt to claim peasant origins implied. At school in Augsburg he met Caspar Neher, with whom he formed a lifelong creative partnership, Neher designing many of the sets for Brecht's dramas and helping to forge the distinctive visual iconography of their epic theatre. When he was 16, the First World War broke out. Initially enthusiastic, Brecht soon changed his mind on seeing his classmates "swallowed by the army".