Copyright by Christelle Georgette Le Faucheur 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

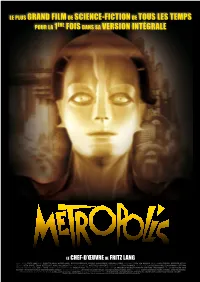

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

The Plays in Translation

The Plays in Translation Almost all the Hauptmann plays discussed in this book exist in more or less acceptable English translations, though some are more easily available than others. Most of his plays up to 1925 are contained in Ludwig Lewisohn's 'authorized edition' of the Dramatic Works, in translations by different hands: its nine volumes appeared between 1912 and 1929 (New York: B.W. Huebsch; and London: M. Secker). Some of the translations in the Dramatic Works had been published separately beforehand or have been reprinted since: examples are Mary Morison's fine renderings of Lonely Lives (1898) and The Weavers (1899), and Charles Henry Meltzer's dated attempts at Hannele (1908) and The Sunken Bell (1899). More recent collections are Five Plays, translated by Theodore H. Lustig with an introduction by John Gassner (New York: Bantam, 1961), which includes The Beaver Coat, Drayman Henschel, Hannele, Rose Bernd and The Weavers; and Gerhart Hauptmann: Three Plays, translated by Horst Frenz and Miles Waggoner (New York: Ungar, 1951, 1980), which contains 150 The Plays in Translation renderings into not very idiomatic English of The Weavers, Hannele and The Beaver Coat. Recent translations are Peter Bauland's Be/ore Daybreak (Chapel HilI: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), which tends to 'improve' on the original, and Frank Marcus's The Weavers (London: Methuen, 1980, 1983), a straightforward rendering with little or no attempt to convey the linguistic range of the original. Wedekind's Spring Awakening can be read in two lively modem translations, one made by Tom Osbom for the Royal Court Theatre in 1963 (London: Calder and Boyars, 1969, 1977), the other by Edward Bond (London: Methuen, 1980). -

Goebbels' Ufa: „Filmschaffen“ Und Ökonomie Elitenbildung Und Unterhaltungsproduktion

Symposium Linientreu und populär. Das Ufa-Imperium 1933 bis 1945 11. und 12. Mai, Filmreihe 11. bis 14. Mai 2017 Symposium Linientreu und populär. Das Ufa-Imperium 1933 bis 1945 Ablauf, Abstracts, Kurzbiografien, Filmreihe Do, 11.05., 13:00 Akkreditierung der Symposiumsteilnehmer*innen Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen im Filmhaus am Potsdamer Platz, Potsdamer Straße 2, 10785 Berlin, Veranstaltungsraum, 4. OG 14:00 Begrüßung: Rainer Rother (Künstlerischer Direktor, Deutsche Kinemathek), Wolf Bauer (Co-CEO UFA GmbH), Ernst Szebedits (Vorstand Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau- Stiftung) 14:30 Block 1 | 100 Jahre Ufa: Rückblicke und Ausblicke Die Ufa im Nationalsozialismus – Die ersten Jahre | Rainer Rother 15:00 Alfred Hugenberg: Wegbereiter der Ufa unterm Hakenkreuz? | Friedemann Beyer 15:30 Zwischen Tradition und Moderne. Zum NS-Kulturfilm 1933–1945 | Kay Hoffmann 16:00 Über die Popularität der Ufa-Filme, 1933–1945. Präsentation von Forschungs- ergebnissen des DFG-Projektes „Begeisterte Zuschauer: Über die Filmpräferenzen der Deutschen im Dritten Reich“ | Joseph Garncarz 16:30 Kaffeepause 17:00 Im Gespräch: Mediale Vermittlung von Zeitgeschichte. Zum Umgang mit brisanten historischen Stoffen | Teilnehmer: Nico Hofmann, Thomas Weber, Moderation: Klaudia Wick 18:00 Zwangsarbeit bei der Ufa | Almuth Püschel 18:30 Die Erinnerungen Piet Reijnens – ein niederländischer Zwangsarbeiter bei der Ufa | Jens Westemeier Ende ca. 19:00 Fr. 12.05., 9:30 Block 2 | Goebbels' Ufa: „Filmschaffen“ und Ökonomie Elitenbildung und Unterhaltungsproduktion. Ufa-Lehrschau und Deutsche Filmakademie als geistiger Ausdruck der Filmstadt Babelsberg im Nationalsozialismus | Rolf Aurich 10:00 Das große Scheitern: Die Ufa als Wirtschaftsunternehmen | Alfred Reckendrees 10:30 Mythos „Filmstadt Babelsberg“. Zur Baugeschichte der legendären Ufa-Filmfabrik | Brigitte Jacob, Wolfgang Schäche 11:15 Kaffeepause 11:45 Der merkwürdige Monsieur Raoul. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessingiiUM-I the World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812304 Comrades, friends and companions: Utopian projections and social action in German literature for young people, 1926-1934 Springman, Luke, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Springman, Luke. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 COMRADES, FRIENDS AND COMPANIONS: UTOPIAN PROJECTIONS AND SOCIAL ACTION IN GERMAN LITERATURE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE 1926-1934 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Luke Springman, B.A., M.A. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Lange Nacht Der Museen JUNGE WILDE & ALTE MEISTER

31 AUG 13 | 18—2 UHR Lange Nacht der Museen JUNGE WILDE & ALTE MEISTER Museumsinformation Berlin (030) 24 74 98 88 www.lange-nacht-der- M u s e e n . d e präsentiert von OLD MASTERS & YOUNG REBELS Age has occupied man since the beginning of time Cranach’s »Fountain of Youth«. Many other loca- – even if now, with Europe facing an ageing popula- tions display different expression of youth culture tion and youth unemployment, it is more relevant or young artist’s protests: Mail Art in the Akademie than ever. As far back as antiquity we find unsparing der Künste, street art in the Kreuzberg Museum, depictions of old age alongside ideal figures of breakdance in the Deutsches Historisches Museum young athletes. Painters and sculptors in every and graffiti at Lustgarten. epoch have tackled this theme, demonstrating their The new additions to the Long Night programme – virtuosity in the characterisation of the stages of the Skateboard Museum, the Generation 13 muse- life. In history, each new generation has attempted um and the Ramones Museum, dedicated to the to reform society; on a smaller scale, the conflict New York punk band – especially convey the atti- between young and old has always shaped the fami- tude of a generation. There has also been a genera- ly unit – no differently amongst the ruling classes tion change in our team: Wolf Kühnelt, who came up than the common people. with the idea of the Long Night of Museums and The participating museums have creatively picked who kept it vibrant over many years, has passed on up the Long Night theme – in exhibitions, guided the management of the project.We all want to thank tours, films, talks and music. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Inhaltsverzeichnis Hinweis 9 Das Theater der Republik 11 Weimar und der Expressionismus 11 Die Väter und die Söhne 12 Die Zerstörung des Dramas 14 Die neuen Schauspieler 16 Die Provinz regt sich 18 Los von Berlin - Los von Reinhardt 20 Berlin und Wien 22 Zersetzter Expressionismus 24 Die große Veränderung 25 Brecht und Piscator 27 Wirklichkeit! Wirklichkeit! 30 Hitler an der Rampe 33 Der große Rest *35 Wieviel wert ist die Kritik? 37 Alte und neue Grundsätze 38 Selbstverständnis und Auseinandersetzungen 41 Die Macht und die Güte 44 *9*7 47 Rene Schickele, Hans im Schnakenloch 48 rb., Frankfurter Zeitung 48 Alfred Kerr, Der Tag, Berlin 50 Siegfried Jacobsohn, Die Schaubühne, Berlin 52 Georg Kaiser, Die Bürger von Calais 53 Kasimir Edschmid, Neue Zürcher Zeitung 54 Heinrich Simon, Frankfurter Zeitung 55 Alfred Polgar, Vossische Zeitung, Berlin 56 Georg Kaiser, Von Morgens bis Mitternachts 57 Richard Elchinger, Münchner Neueste Nachrichten 58 Richard Braungart, Münchener Zeitung 60 P. S., Frankfurter Zeitung 61 Richard Specht, Berliner Börsen-Courier 62 Oskar Kokoschka, Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen - Hiob - Der bren nende Dornbusch 63 Robert Breuer, Die Schaubühne, Berlin 64 Bernhard Diebold, Frankfurter Zeitung 66 Alfred Kerr, Der Tag, Berlin 69 Gerhart Hauptmann, Winterballade .. 72 Siegfried Jacobsohn, Die Schaubühne, Berlin 73 Julius Hart, Der Tag, Berlin 75 Emil Faktor, Berliner Börsen-Courier 77 1248 http://d-nb.info/207309981 Georg Kaiser, Die Koralle 79 Bernhard Diebold, Frankfurter Zeitung 79 Kasimir Edschmid, Vossische Zeitung, Berlin, und Neue Zürcher Zei tung 82 Emil Faktor, Berliner Börsen-Courier 83 Alfred Kerr, Der Tag, Berlin 84 Hanns Johst, Der Einsame, ein Menschenuntergang 86 Artur Kutscher, Berliner Tageblatt . -

Der Auftakt 1920-1938

Der Auftakt 1920-1938 The Prague music journal Der Auftakt [The upbeat. AUF. Subtitle: “Musikblätter für die tschechoslowakische Republik;” from volume seven, issue two “Moderne Musikblätter”]1 appeared from December 1920 to April 1938.2 According to Felix Adler (1876-1928), music critic for the Prague journal Bohemia and editor of the first eight issues of AUF,3 the journal was formed out of the Musiklehrerzeitung [Journal for music teachers] (1913-16, organ of the Deutscher Musikpädagogischer Verband [German association for music pedagogy] in Prague) and was to be a general music journal with a modern outlook and with a concern for the interests of music pedagogues.4 Under its next editor, Erich Steinhard, AUF soon developed into one of the leading German-language modern music journals of the time and became the center of Czech-German musical collaboration in the Czechoslovakian Republic between the wars.5 Adolf Weißmann, eminent music critic from Berlin, writes: “Among the journals that avoid all distortions of perspective, the Auftakt stands at the front. It has gained international importance through the weight of its varied contributions and the clarity of mind of its main editor.”6 The journal stopped publication without prior announcement in the middle of volume eighteen, likely a result of the growing influence of Nazi Germany.7 AUF was published at first by Johann Hoffmanns Witwe, Prague, then, starting with the third volume in 1923, by the Auftaktverlag, a direct venture of the Musikpädagogischer Verband.8 The journal was introduced as a bimonthly publication, but except for the first volume appearing in twenty issues from December 1920 to the end of 1921, all volumes contain twelve monthly issues, many of them combined into double issues.9 The issues are undated, but a line with the date for the “Redaktionsschluss” [copy deadline], separating the edited content from the 1 Subtitles as given on the first paginated page of every issue.