The Plays in Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Artxsr, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* NOTE TO USERS Page(s) missing in number only; text follows. Page(s) were microfilmed as received. 131,172 This reproduction is the best copy available UMI FRANK WEDEKIND’S FANTASY WORLD: A THEATER OF SEXUALITY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Bv Stephanie E. -

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples Mittelalter (1150- Wolfram von Eschenbach Epik Parzival (1200/1210) 1450) Gottfried von Straßburg Tristan (ca. 1210) Hartmann von Aue Der arme Heinrich (ca. 1195) Johannes von Tepl Der Ackermann aus Böhmen (ca. 1400) Walther von der Vogelweide Lieder, Oskar von Wolkenstein Minnelyrik, Spruchdichtung Gedichte Renaissance Martin Luther Prosa Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen (1530) (1400-1600) Von der Freyheit eynis Christen Menschen (1521) Historia von D. Johann Fausten (1587) Das Volksbuch vom Eulenspiegel (1515) Der ewige Jude (1602) Sebastian Brant Das Narrenschiff (1494) Barock (1600- H.J.C. von Grimmelshausen Prosa Der abenteuerliche Simplizissimus Teutsch (1669) 1720) Schelmenroman Martin Opitz Lyrik Andreas Gryphius Paul Fleming Sonett Christian v. Hofmannswaldau Paul Gerhard Aufklärung (1720- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Prosa Fabeln 1785) Christian Fürchtegott Gellert Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Drama Nathan der Weise (1779) Bürgerliches Emilia Galotti (1772) Trauerspiel Miss Sara Samson (1755) Lustspiel Minna von Barnhelm oder das Soldatenglück (1767) 2 Sturm und Drang Johann Wolfgang Goethe Prosa Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (1774) (1767-1785) Johann Gottfried Herder Von deutscher Art und Kunst (selections; 1773) Karl Philipp Moritz Anton Reiser (selections; 1785-90) Sophie von Laroche Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim (1771/72) Johann Wolfgang Goethe Drama Götz von Berlichingen (1773) Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz Der Hofmeister oder die Vorteile der Privaterziehung (1774) -

Carl Und Gerhart Hauptmann – Jahrbuch

Carl und Gerhart Hauptmann – Jahrbuch Bd. VII 2013 Carl und Gerhart Hauptmann - Jahrbuch Redaktion Prof. Dr. Krzysztof A. Kuczyński Katedra Badań Niemcoznawczych \ Lehrstuhl für Deutschlandstudien Uniwersytet Łódzki \ Universität Lodz ul. Narutowicza 59 a, PL 90- 131 Łódź Tel.\Fax. 0048 -42 – 66 55 401 E-Mail: [email protected] Herausgeber der Reihe „Carl und Gerhart Hauptmann – Jahrbuch“ Prof. Dr. Krzysztof A. Kuczyński Herausgeber des Bandes VII, 2013 Prof. Dr. Grażyna Barbara Szewczyk Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Marek Hałub Uniwersytet Wrocławski \ Universität Wrocław Wissenschaftlicher Beirat: Prof. Dr. Mirosława Czarnecka, Universität Wrocław Prof. Dr. Marek Hałub, Universität Wrocław Prof. Dr. Peter Sprengel, FU Berlin Prof. Dr. Anna Stroka, Universität Wrocław Prof. Dr. Grażyna Szewczyk, Universität Katowice ISSN 2084-2511 Vertrieb des Carl und Gerhart Hauptmann-Jahrbuchs Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa we Włocławku / Staatliche Fachhochschule Włocławek Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWSZ we Włocławku Wissenschaftlicher Verlag der Staatlichen Fachhochschule in Włocławek PL 87-800 Włocławek, ul. 3 Maja 17 Fax: 0048 54 321 43 52 E-Mail: [email protected] * Für unverlangt eingesandte Materialien wird keine Haftung übernommen Skład, druk i oprawa Partner Poligrafia Białystok, ul. Zwycięstwa 10; tel. 85 653-78-04; [email protected] Lehrstuhl für Deutschlandstudien der Universität Łódź Gerhart-Hauptmann-Museum Erkner Carl und Gerhart Hauptmann – Jahrbuch Bd. VII Wissenschaftlicher Verlag der Staatlichen Fachhochschule in Włocławek -

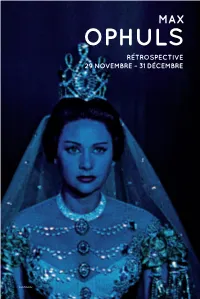

Max-Ophuls.Pdf

MAX OPHULS RÉTROSPECTIVE 29 NOVEMBRE – 31 DÉCEMBRE Lola Montès Divine GRAND STYLE Né en Allemagne, auteur de plusieurs mélodrames stylés en Allemagne, en Italie et en France dans les années 1930 (Liebelei, La signora di tutti, De Mayerling à Sarajevo), Max Ophuls tourne ensuite aux États-Unis des films qui tranchent par leur secrète inspiration « mitteleuropa » avec la tradition hollywoodienne (Lettre d’une inconnue). Il rentre en France et signe coup sur coup La Ronde, Le Plaisir, Madame de… et Lola Montès. Max Ophuls concevait le cinéma comme un art du spectacle. Un art de l’espace et du mouvement, susceptible de s’allier à la littérature et de s’inspirer des arts plastiques, mais un art qu’il pratiquait aussi comme un art du temps, apparen- té en cela à la musique, car il était de ceux – les artistes selon Nietzsche – qui sentent « comme un contenu, comme « la chose elle-même », ce que les non- artistes appellent la forme. » Né Max Oppenheimer en 1902, il est d’abord acteur, puis passe à la mise en scène de théâtre, avant de réaliser ses premiers films entre 1930 et 1932, l’année où, après l’incendie du Reichstag, il quitte l’Allemagne pour la France. Naturalisé fran- çais, il doit de nouveau s’exiler après la défaite de 1940, travaille quelques années aux États-Unis puis regagne la France. LES QUATRE PÉRIODES DE L’ŒUVRE CINEMATHEQUE.FR Dès 1932, Liebelei donne le ton. Une pièce d’Arthur Schnitzler, l’euphémisme de Max Ophuls, mode d’emploi : son titre, « amourette », qui désigne la passion d’une midinette s’achevant en retrouvez une sélection tragédie, et la Vienne de 1900 où la frivolité contraste avec la rigidité des codes subjective de 5 films dans la sociaux. -

Revising the World with Speech in Franz Kafka, Robert Walser and Thomas Bernhard

Monologue Overgrown: Revising the world with speech in Franz Kafka, Robert Walser and Thomas Bernhard by Paul Joseph Buchholz This thesis/dissertation document has been electronically approved by the following individuals: Schwarz,Anette (Chairperson) Gilgen,Peter (Minor Member) McBride,Patrizia C. (Minor Member) MONOLOGUE OVERGROWN: REVISING THE WORLD WITH SPEECH IN FRANZ KAFKA, ROBERT WALSER AND THOMAS BERNHARD A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Paul Joseph Buchholz August 2010 © 2010 Paul Joseph Buchholz MONOLOGUE OVERGROWN: REVISING THE WORLD WITH SPEECH IN FRANZ KAFKA, ROBERT WALSER AND THOMAS BERNHARD Paul Joseph Buchholz, Ph. D. Cornell University 2010 My dissertation focuses on unstable, chronically unpublished prose texts by three key 20th century prose writers, quasi-novelistic texts whose material instability indicates a deep discomfort with the establishment of narrative authority qua narrative violence. I argue that Franz Kafka, Robert Walser and Thomas Bernhard, radically refunctionalized the device of interpolated “character monologue,” turning characters' speech from a narrative function, into a site where a text can be rewritten from within. In the Bildungsroman tradition, extended oral interpolations serve as an engine for the expansion and exposition of the plotted work, deepening the epic narrative world and exhaustively presenting a perspective that will be incorporated into biographical trajectory. I locate an estrangement of this practice: moments when oral monologues of fictional interlocutors “overgrow,” becoming an interventionary force that doubles, disrupts and re-frames the narrative discourse out of which it first sprouted. In showing how the labor of ‘world-making’ is split and spread across different competing layers of these texts, my dissertation contributes to the study of the narrative phenomenon of metalepsis. -

(Student Performance Objectives) Ccos

COURSE OUTLINE : GRMN 012 Last Revised and Approved: 10/23/2008 CURRICULUM Subject Code and Course Number: GRMN 012 Division : Languages Course Title : GERMAN LITERATURE IN TRANSLATION Summarize the need/purpose/reason for this proposal German 12 appeals to the general college population as well as students already enrolled in German language classes. Since the German program cannot offer literature courses in German at this point, reading major works in translation is the next best thing. Furthermore, a survey of German literary movements enhances students' understanding of the history and culture of the German-speaking countries and complements the popular German Civilization course. Beyond that, studying works of German literature that represent different historical periods and cultural contexts will challenge students to analyze broader issues and ideas and make connections with global themes addressed in other courses in the Languages, English, and Social Sciences Divisions. Finally, Literature in Translation is already well established in the Languages Division in these foreign language classes: Chinese 12, Japanese 12, Spanish 12, and Italian 12. SLOs (Student Learning Outcomes) 1. Recognize and discuss key characteristics of major periods of German literature. 2. Compare and contrast dominant themes, relevant topics, and stylistic conventions in representative works. SPOs (Student Performance Objectives) 1. Describe core characteristics of major movements in German literature 2. Demonstrate a basic knowledge of the geography, history and culture of Germany 3. Analyze individual works of literature in their historical, socio-economic and philosophical context 4. Identify elements of style and structure in different genres of literature 5. Relate German literary themes and traditions to prevalent trends in world literature CCOs (Course Content Outline) Note: This outline lists all topics of interest. -

David Hare's the Blue Room and Stanley

Schnitzler as a Space of Central European Cultural Identity: David Hare’s The Blue Room and Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut SUSAN INGRAM e status of Arthur Schnitzler’s works as representative of fin de siècle Vien- nese culture was already firmly established in the author’s own lifetime, as the tributes written in on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday demonstrate. Addressing Schnitzler directly, Hermann Bahr wrote: “As no other among us, your graceful touch captured the last fascination of the waning of Vi- enna, you were the doctor at its deathbed, you loved it more than anyone else among us because you already knew there was no more hope” (); Egon Friedell opined that Schnitzler had “created a kind of topography of the constitution of the Viennese soul around , on which one will later be able to more reliably, more precisely and more richly orient oneself than on the most obese cultural historian” (); and Stefan Zweig noted that: [T]he unforgettable characters, whom he created and whom one still could see daily on the streets, in the theaters, and in the salons of Vienna on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday, even yesterday… have suddenly disappeared, have changed. … Everything that once was this turn-of-the-century Vienna, this Austria before its collapse, will at one point… only be properly seen through Arthur Schnitzler, will only be called by their proper name by drawing on his works. () With the passing of time, the scope of Schnitzler’s representativeness has broadened. In his introduction to the new English translation of Schnitzler’s Dream Story (), Frederic Raphael sees Schnitzler not only as a Viennese writer; rather “Schnitzler belongs inextricably to mittel-Europa” (xii). -

PDF Downloaden

Volkswirtschaft und Theater: Ernst und Spiel, Brotarbeit und Zirkus, planmäßige Geschäftigkeit und Geschäftlichkeit und auf der anderen Seite Unterhaltung und Vergnügen! Und doch hat eine jahrhundertelange Entwicklung ein Band, beinahe eine Kette zwischen beiden geschaffen, gehämmert und geschmiedet. Max Epstein1 The public has for so long seen theatrical amusements carried on as an industry, instead of as an art, that the disadvantage of apply- ing commercialism to creative work escapes comment, as it were, by right of custom. William Poel2 4. Theatergeschäft Theater als Geschäft – das scheint heute zumindest in Deutschland, wo fast alle Theater vom Staat subventioniert werden, ein Widerspruch zu sein. Doch schon um 1900 waren für die meisten deutschen Intellektuellen Geschäft und Theater, Kunst und Kommerz unvereinbare Gegensätze. Selbst für jemanden, der so inten- siv und über lange Jahre hinweg als Unternehmer, Anwalt und Journalist mit dem Geschäftstheater verbunden war wie Max Epstein, schlossen sie einander letztlich aus. Obwohl er lange gut am Theater verdient hatte, kam er kurz vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg zu dem Schluss: „Das Theatergeschäft hat die Bühnenkunst ruiniert“.3 In Großbritannien hingegen, wo Theater seit der Zeit Shakespeares als private, kommerzielle Unternehmen geführt wurden, war es völlig selbstverständlich, im Theater eine Industrie zu sehen. Der Schauspieler, Direktor und Dramatiker Wil- liam Poel bezeugte diese Haltung und war zugleich einer der ganz wenigen, der sie kritisierte. Wie auch immer man den Prozess bewertete, Tatsache war, dass Theater in der Zeit der langen Jahrhundertwende in London wie in Berlin überwiegend kom- merziell angeboten wurde. Zwar gilt dies teilweise bereits für die frühe Neuzeit, erst im Laufe des 19. -

Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man Jeffrey Erik Berry Bates College, [email protected]

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects Spring 5-2012 Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man Jeffrey Erik Berry Bates College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Berry, Jeffrey Erik, "Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man" (2012). Honors Theses. 10. http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/10 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Departments of History and of German & Russian Studies Bates College In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Jeffrey Berry Lewiston, Maine 23 March 2012 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis advisors, Professor Craig Decker from the Department of German and Russian Studies and Professor Jason Thompson of the History Department, for their patience, guidance and expertise during this extensive and rewarding process. I also would also like to extend my sincere gratitude to the people who will be participating in my defense, Professor John Cole of the Bates College History Department, Profesor Raluca Cernahoschi of the Bates College German Department, and Dr. Richard Blanke from the University of Maine at Orno History Department, for their involvement during the culminating moment of my thesis experience. Finally, I would like to thank all the other people who were indirectly involved during my research process for their support. -

GRMN 451.01: 20Th Century German Literature to 1945

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Spring 2-1-2019 GRMN 451.01: 20th Century German Literature to 1945 Hiltrudis Arens University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Arens, Hiltrudis, "GRMN 451.01: 20th Century German Literature to 1945" (2019). Syllabi. 10326. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/10326 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Twentieth Century German Literature to 1945 GRMN 451 MWF 2:00-2:50pm Spring 2019 Contact Professor: Dr. Hiltrud Arens Office: LA 441 Office hours: Mon/Wed: 11:00-11:50 Uhr; 15:00-15:50:00 Uhr; or/and by appointment Telefon: 243-5634 (office) Email: [email protected] Language of instruction is German Learning Goals: 1) To give an introduction and a survey of turn of the century German-language literary works (also in translation available) up to 1945. 2) To examine a variety of genres, including novel, novella, short story, essay, letter, poetry, drama, and film; and to connect those to other medial forms like painting, graphic arts, music, and photography, as well as to other societal/scientific developments, such as psycho-analysis. 3) To obtain formal knowledge through studying the texts (primary and secondary texts) in terms of language usage, style, and structure. -

Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann: a Struggle of German-Jewish Identities

University of Cambridge Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages Department of German and Dutch Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann: A Struggle of German-Jewish Identities This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Max Matthias Walter Haberich Clare Hall Supervisor: Dr. David Midgley St. John’s College Easter Term 2013 Declaration of Originality I declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work. This thesis includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. Signed: June 2013 Statement of Length With a total count of 77.996 words, this dissertation does not exceed the word limit as set by the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages, University of Cambridge. Signed: June 2013 Summary of Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann: A Struggle of German- Jewish Identities by Max Matthias Walter Haberich The purpose of this dissertation is to contrast the differing responses to early political anti- Semitism by Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann. By drawing on Schnitzler’s primary material, it becomes clear that he identified with certain characters in Der Weg ins Freie and Professor Bernhardi. Having established this, it is possible to trace the development of Schnitzler’s stance on the so-called ‘Jewish Question’: a concept one may term enlightened apolitical individualism. Enlightened for Schnitzler’s rejection of Jewish orthodoxy, apolitical because he always remained strongly averse to politics in general, and individualism because Schnitzler felt there was no general solution to the Jewish problem, only one for every individual. For him, this was mainly an ethical, not a political issue; and he defends his individualist position in Professor Bernhardi.