Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alfred Adlers Wiener Kreise in Politik, Literatur Und Psychoanalyse

Almuth Bruder-Bezzel Alfred Adlers Wiener Kreise in Politik, Literatur und Psychoanalyse Beiträge zur Geschichte der Individualpsychologie Titel Autor © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525406359 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647406350 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525406359 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647406350 Almuth Bruder-Bezzel Alfred Adlers Wiener Kreise in Politik, Literatur und Psychoanalyse Beiträge zur Geschichte der Individualpsychologie Mit 15 Abbildungen Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525406359 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647406350 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.de abrufbar. © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Theaterstraße 13, D-37073 Göttingen Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk und seine Teile sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung in anderen als den gesetzlich zugelassenen Fällen bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Einwilligung des Verlages. Umschlagabbildung: Café Central, Wien/INTERFOTO/JTB PHOTO Satz: SchwabScantechnik, Göttingen Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com ISBN 978-3-647-40635-0 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525406359 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647406350 Inhalt Einleitung ......................................... -

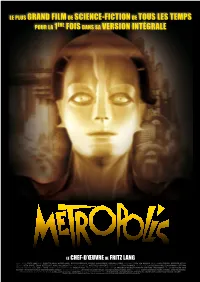

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Morina on Forner, 'German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics After 1945'

H-German Morina on Forner, 'German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics after 1945' Review published on Monday, April 18, 2016 Sean A. Forner. German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics after 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. xii +383 pp. $125.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-107-04957-4. Reviewed by Christina Morina (Friedrich-Schiller Universität Jena) Published on H-German (April, 2016) Commissioned by Nathan N. Orgill Envisioning Democracy: German Intellectuals and the Quest for Democratic Renewal in Postwar German As historians of twentieth-century Germany continue to explore the causes and consequences of National Socialism, Sean Forner’s book on a group of unlikely affiliates within the intellectual elite of postwar Germany offers a timely and original insight into the history of the prolonged “zero hour.” Tracing the connections and discussions amongst about two dozen opponents of Nazism, Forner explores the contours of a vibrant debate on the democratization, (self-) representation, and reeducation of Germans as envisioned by a handful of restless, self-perceived champions of the “other Germany.” He calls this loosely connected intellectual group a network of “engaged democrats,” a concept which aims to capture the broad “left” political spectrum they represented--from Catholic socialism to Leninist communism--as well as the relative openness and contingent nature of the intellectual exchange over the political “renewal” of Germany during a time when fixed “East” and “West” ideological fault lines were not quite yet in place. Forner enriches the already burgeoning historiography on postwar German democratization and the role of intellectuals with a profoundly integrative analysis of Eastern and Western perspectives. -

Information Issued by The

Vol. XV No. 10 October, 1960 INFORMATION ISSUED BY THE. ASSOCIATION OF JEWISH REFUGEES IN GREAT BRITAIN t FAIRFAX MANSIONS, FINCHLEY ROAD (Comer Fairfax Road), Offict and Consulting Hours : LONDON, N.W.3 Monday to Thursday 10 a.m.—I p.m. 3—6 p.m. Talephona: MAIda Vala 9096'7 (General Officel Friday 10 a.m.—I p.m. MAIda Vale 4449 (Employment Agency and Social Services Dept.} 'Rudolf Hirschfeld (Monlevideo) a few others. Apart from them, a list of the creators of all these important German-Jewish organisations in Latin America would hardly con tain a name of repute outside the continent. It GERMAN JEWS IN SOUTH AMERICA it without any doubt a good sign that post-1933 German Jewry has been able to produce an entirely new generation of vigorous and success I he history of the German-Jewish organisations abroad '"—to assert this would be false—they ful leaders. =8ins in each locality the moment the first ten consider themselves as the sons of the nation In conclusion two further aspects have to be r^Ple from Germany disembark. In the few which has built up the State of Israel, with the mentioned : the relationship with the Jews around thp "if- ^^^^^ Jewish groups were living before consciousness that now at last they are legitimate us, and the future of the community of Jews from ne Hitler period the immigrants were helped by members of the national families of the land they Central Europe. Jewish life in South America ne earlier arrivals. But it is interesting that this inhabit at present. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

Renan De Andrade Varolli

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS RENAN DE ANDRADE VAROLLI O MODERNO NA ILUMINAÇÃO ELÉTRICA EM BERLIM NOS ANOS 1920 SÃO PAULO 2017 RENAN DE ANDRADE VAROLLI O MODERNO NA ILUMINAÇÃO ELÉTRICA EM BERLIM NOS ANOS 1920 Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em História da Arte Universidade Federal de São Paulo Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Arte Linha de Pesquisa: Arte: Circulações e Transferências Orientação: Prof. Dr. Jens Michael Baumgarten SÃO PAULO 2017 Varolli, Renan de Andrade. O moderno na iluminação elétrica em Berlim nos anos 1920 / Renan de Andrade Varolli. São Paulo, 2017. 129 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em História da Arte) – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Escola de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Programa de Pós- Graduação em História da Arte, 2017. Orientação: Prof. Dr. Jens Michael Baumgarten. 1. Teoria da Arte. 2. História da Arte. 3. Teoria da Arquitetura. I. Prof. Dr. Jens Michael Baumgarten. II. O moderno na iluminação elétrica em Berlim nos anos 1920. RENAN DE ANDRADE VAROLLI O MODERNO NA ILUMINAÇÃO ELÉTRICA EM BERLIM NOS ANOS 1920 Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em História da Arte Universidade Federal de São Paulo Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Arte Linha de Pesquisa: Arte: Circulações e Transferências Orientação: Prof. Dr. Jens Michael Baumgarten Aprovação: ____/____/________ Prof. Dr. Jens Michael Baumgarten Universidade Federal de São Paulo Prof. Dr. Luiz César Marques Filho Universidade Estadual de Campinas Profa. Dra. Yanet Aguilera Viruéz Franklin de Matos Universidade Federal de São Paulo AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço às seguintes pessoas, que tornaram possível a realização deste trabalho: Aline, Ana Carolina, minha prima, Ana Paula, Bi, Carla, Daniel, Diana, Fá, Fê, Gabi, Gabriel, Giovanna, Jair, meu pai, Jane, minha tia e madrinha, Prof. -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Al-'Usur Al-Wusta, Volume 23 (2015)

AL-ʿUṢŪR AL-WUSṬĀ 23 (2015) THE JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS About Middle East Medievalists (MEM) is an international professional non-profit association of scholars interested in the study of the Islamic lands of the Middle East during the medieval period (defined roughly as 500-1500 C.E.). MEM officially came into existence on 15 November 1989 at its first annual meeting, held ni Toronto. It is a non-profit organization incorporated in the state of Illinois. MEM has two primary goals: to increase the representation of medieval scholarship at scholarly meetings in North America and elsewhere by co-sponsoring panels; and to foster communication among individuals and organizations with an interest in the study of the medieval Middle East. As part of its effort to promote scholarship and facilitate communication among its members, MEM publishes al-ʿUṣūr al-Wusṭā (The Journal of Middle East Medievalists). EDITORS Antoine Borrut, University of Maryland Matthew S. Gordon, Miami University MANAGING EDITOR Christiane-Marie Abu Sarah, University of Maryland EDITORIAL BOARD, BOARD OF DIRECTORS, AL-ʿUṢŪR AL-WUSṬĀ (THE JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS) MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS Zayde Antrim, Trinity College President Sobhi Bourdebala, University of Tunis Matthew S. Gordon, Miami University Muriel Debié, École Pratique des Hautes Études Malika Dekkiche, University of Antwerp Vice-President Fred M. Donner, University of Chicago Sarah Bowen Savant, Aga Khan University David Durand-Guédy, Institut Français de Recherche en Iran and Research -

Court Jewsof Southern Germany

COURT JEWS OF SOUTHERN GERMANY VERSION 08 of Darmstadt (Hesse), Harburg (County of Oettingen), Hechingen (Hohenzollern), Stuttgart (Wuerttemberg) DAVID ULMANN Incomplete extract of a general structure by Rolf Hofmann ( [email protected] ) plus additional information from Otto Werner (Hechingen) Court Jew in Pfersee Red numbers indicate graves at Jewish cemetery of Hechingen ? ? RAPHAEL ISAAC (1713 Buchau – 1759 Sigmaringen) JOSEPH ISAAK ELIESER LAZARUS DAVID ULMANN Court Jew in Hechingen and Sigmaringen ROEDER called LIEBMANN, son of JACOB Court Jew in Harburg in 1764 married LEA JEANETTE in Harburg (died 1823) Parnas and Manhig of Hechingen (died 1771 in Harburg) REBEKKA WASSERMANN of Regensburg (died 1796 in Hechingen) RAPHAEL KAULLA married ca 1776 (died 1795) grave 752 married 1751 married ZORTEL (1758 - 1834) married 1774 as a widower VEJA, daughter of Parnas SALOMON REGENSBURGER VEJA, widow of Court Jew Gumperle Kuhn of Harburg, Court Jew in Donaueschingen Lazarus David Ulmann in Harburg who in 1774 married ELIESER who died 1795 in Hechingen (she died 1805 in Wallerstein) JAKOB KAULLA MADAME KAULLA HIRSCH RAPHAEL MAIER KAULLA business partner of Court Jewess in KAULLA Court Jew in Hanau AARON LIEBMANN HEINRICH JAKOB LIPPMANN LDU's daughter ZIERLE Madame Kaulla, Hechingen + Stuttgart Court Jew in Darmstadt 1757 – 1815 grv 485 Court Jew in Hechingen HARBURGER HECHINGER (died in Wallerstein 1822) Court Jew in 1739 – 1809 (grave 483) 1756 – 1798 married 1788 and Vienna (since 1807) (later ROEDER) Court Jew in Harburg (1803) married -

1 Stephanie Zibell: Vor 80 Jahren: Als Die Hakenkreuzflagge Über

Stephanie Zibell: Vor 80 Jahren: Als die Hakenkreuzflagge über Darmstadt wehte. Kollegiengebäude und Landesverwaltung zwischen Machtergreifung und demokratischem Neubeginn. Vortrag aus Anlass der Gedenkveranstaltung zum 80. Jahrestag der „Machtergreifung“ durch die Nationalsozialisten. Einleitung Als mich Herr Regierungspräsident Baron im vergangenen Jahr ansprach und mich bat, am heutigen Tag einen Vortrag zu halten, habe ich dem Ansinnen insofern gerne entsprochen, als ich mich in meiner Dissertation mit dem in Darmstadt amtierenden hessischen Reichsstatthalter und Gauleiter Jakob Sprenger beschäftigt habe, von dem wir heute noch hören werden, und in meiner Habilitationsschrift mit Ludwig Bergsträsser, der hier in Darmstadt zwischen 1945 und 1948 als erster Regierungspräsident amtiert hat. Ihm, Ludwig Bergsträsser, ist heute eine ganz besondere Ehrung zuteil geworden, über die ich mich persönlich sehr freue: Der bisherige Sitzungssaal Süd ist in Ludwig-Bergsträsser-Saal umbenannt worden. Ich habe davon auch meinem Doktorvater, Prof. Dr. Hans Buchheim, berichtet, der Ludwig Bergsträsser noch persönlich gekannt hat und dafür verantwortlich zeichnet, dass ich mich so intensiv mit Bergsträsser beschäftigt habe. Auch Herr Buchheim, der heute hier anwesend ist, zeigte sich sehr erfreut. Doch wie der Titel meines Vortrags und der einleitende Hinweis auf den Nationalsozialisten Jakob Sprenger bereits andeutet: Es wird in der nächsten Stunde nicht nur Erfreuliches zu hören sein, sondern auch Tragisches und Betrübliches. Ich werde im Folgenden von den Ereignissen berichten, die die nationalsozialistische „Machtübernahme“ am 30. Januar 1933 in Darmstadt, damals Hauptstadt des Volksstaats Hessen, und in Wiesbaden, dem Sitz des Regierungspräsidiums des Regierungsbezirks Wiesbaden der preußischen Provinz Hessen-Nassau, nach sich zog. Das preußische Wiesbaden erwähne ich, weil es vor 1945 im Volksstaat Hessen kein Regierungspräsidium gab. -

Fritz Lang © 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May Be Used for Personal Purporses Only Or by Reihe Filmlibraries 7 Associated to Dandelon.Com Network

Fritz Lang © 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May be used for personal purporses only or by Reihe Filmlibraries 7 associated to dandelon.com network. Mit Beiträgen von Frieda Grafe Enno Patalas Hans Helmut Prinzler Peter Syr (Fotos) Carl Hanser Verlag Inhalt Für Fritz Lang Einen Platz, kein Denkmal Von Frieda Grafe 7 Kommentierte Filmografie Von Enno Patalas 83 Halbblut 83 Der Herr der Liebe 83 Der goldene See. (Die Spinnen, Teil 1) 83 Harakiri 84 Das Brillantenschiff. (Die Spinnen, Teil 2) 84 Das wandernde Bild 86 Kämpfende Herzen (Die Vier um die Frau) 86 Der müde Tod 87 Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler 88 Die Nibelungen 91 Metropolis 94 Spione 96 Frau im Mond 98 M 100 Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse 102 Liliom 104 Fury 105 You Only Live Once. Gehetzt 106 You and Me [Du und ich] 108 The Return of Frank James. Rache für Jesse James 110 Western Union. Überfall der Ogalalla 111 Man Hunt. Menschenjagd 112 Hangmen Also Die. Auch Henker sterben 113 Ministry of Fear. Ministerium der Angst 115 The Woman in the Window. Gefährliche Begegnung 117 Scarlet Street. Straße der Versuchung 118 Cloak and Dagger. Im Geheimdienst 120 Secret Beyond the Door. Geheimnis hinter der Tür 121 House by the River [Haus am Fluß] 123 American Guerrilla in the Philippines. Der Held von Mindanao 124 Rancho Notorious. Engel der Gejagten 125 Clash by Night. Vor dem neuen Tag 126 The Blue Gardenia. Gardenia - Eine Frau will vergessen 128 The Big Heat. Heißes Eisen 130 Human Desire. Lebensgier 133 Moonfleet. Das Schloß im Schatten 134 While the City Sleeps. -

The Stage of the Mountains

Leopold- Franzens Universität Innsbruck The Stage of the Mountains A TRANSNATIONAL AND HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE MOUNTAINS AS A STAGE IN 100 YEARS OF MOUNTAIN CINEMA Diplomarbeit Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Mag. phil. an der Philologisch- Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Eingereicht bei PD Mag. Dr. Christian Quendler von Maximilian Büttner Innsbruck, im Oktober 2019 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt durch meine eigenhändige Unterschrift, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich den angegebenen Quellen entnommen wurden, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch nicht als Magister- /Master-/Diplomarbeit/Dissertation eingereicht. ______________________ ____________________________ Datum Unterschrift Table of Contents Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 Mountain Cinema Overview ................................................................................................... 4 The Legacy: Documentaries, Bergfilm and Alpinism ........................................................... 4 Bergfilm, National Socialism and Hollywood