Dr.Thesis Kristoffer Momrak.Pdf (1.926Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ROMANCE of BIBLE CHRONOLOGY Rev

THE ROMANCE OF BIBLE CHRONOLOGY Rev. Martin Anstey, BA, MA An Exposition of the Meaning, and a Demonstration of the Truth, of Every Chronological Statement Contained in the Hebrew Text of the Old Testament Marshall Brothers, Ltd., London, Edinburgh and New York 1913. DEDICATION To my dear Friend Rev. G. Campbell Morgan, D.D. to whose inspiring Lectures on “The Divine Library in Human History” I trace the inception of these pages, and whose intimate knowledge and unrivalled exposition of the Written Word makes audible in human ears the Living Voice of the Living God, I dedicate this book. The Author October 3rd, 1913 FOREWORD BY REV. G. CAMPBELL MORGAN, D. D. It is with pleasure, and yet with reluctance, that I have consented to preface this book with any words of mine. The reluctance is due to the fact that the work is so lucidly done, that any setting forth of the method or purpose by way of introduction would be a work of supererogation. The pleasure results from the fact that the book is the outcome of our survey of the Historic move- ment in the redeeming activity of God as seen in the Old Testament, in the Westminster Bible School. While I was giving lectures on that subject, it was my good fortune to have the co—operation of Mr. Mar- tin Anstey, in a series of lectures on these dates. My work was that of sweeping over large areas, and largely ignoring dates. He gave his attention to these, and the result is the present volume, which is in- valuable to the Bible Teacher, on account of its completeness and detailed accuracy. -

The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20Th Century

Review of General Psychology Copyright 2002 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 2002, Vol. 6, No. 2, 139–152 1089-2680/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//1089-2680.6.2.139 The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20th Century Steven J. Haggbloom Renee Warnick, Jason E. Warnick, Western Kentucky University Vinessa K. Jones, Gary L. Yarbrough, Tenea M. Russell, Chris M. Borecky, Reagan McGahhey, John L. Powell III, Jamie Beavers, and Emmanuelle Monte Arkansas State University A rank-ordered list was constructed that reports the first 99 of the 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. Eminence was measured by scores on 3 quantitative variables and 3 qualitative variables. The quantitative variables were journal citation frequency, introductory psychology textbook citation frequency, and survey response frequency. The qualitative variables were National Academy of Sciences membership, election as American Psychological Association (APA) president or receipt of the APA Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award, and surname used as an eponym. The qualitative variables were quantified and combined with the other 3 quantitative variables to produce a composite score that was then used to construct a rank-ordered list of the most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. The discipline of psychology underwent a eve of the 21st century, the APA Monitor (“A remarkable transformation during the 20th cen- Century of Psychology,” 1999) published brief tury, a transformation that included a shift away biographical sketches of some of the more em- from the European-influenced philosophical inent contributors to that transformation. Mile- psychology of the late 19th century to the stones such as a new year, a new decade, or, in empirical, research-based, American-dominated this case, a new century seem inevitably to psychology of today (Simonton, 1992). -

Ordines Militares Conference

ORDINES◆ MILITARES COLLOQUIA TORUNENSIA HISTORICA Yearbook for the Study of the Military Orders vol. XIX (2014) Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika Towarzystwo Naukowe w Toruniu Toruń 2014 Editorial Board Roman Czaja, Editor in Chief, Nicolaus Copernicus University Toruń Jürgen Sarnowsky, Editor in Chief, University of Hamburg Jochen Burgtorf, California State University Sylvain Gouguenheim, École Normale Supérieure Lettres et Sciences Humaines de Lyon Hubert Houben, Università del Salento Lecce Alan V. Murray, University of Leeds Krzysztof Kwiatkowski, Assistant Editor, Nicolaus Copernicus University Toruń Reviewers: Udo Arnold, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn (retired) Karl Borchardt, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, München Jochen Burgtorf, Department of History, California State University Wiesław Długokęcki, Institute of History, University of Gdańsk Marie-Luise Favreau-Lilie, Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut, Freie Universität Berlin Alan Forey, Durham University (retired) Mario Glauert, Brandenburgisches Landeshauptarchiv in Potsdam Sylvain Gouguenheim, Ecole Normale Supérieure Lettres et Sciences Humaines de Lyon Dieter Heckmann, Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin-Dahlem Ilgvars Misāns, Faculty of History and Philosophy, University of Latvia, Riga Maria Starnawska, Institute of History, Jan Długosz University in Częstochowa Sławomir Zonenberg, Institute of History and International Relationships, Kazimierz Wielki University in Bydgoszcz Janusz Tandecki, Institut of History and Archival Sciences, Nicolaus -

John Ashbery 125 Part Twelve the Voyages of John Matthias 133

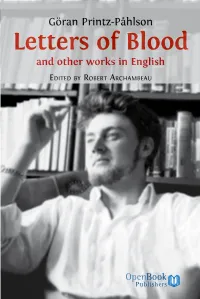

Göran Printz-Påhlson Letters of Blood and other works in English EDITED BY ROBERT ARCHAMBEAU To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/86 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Letters of Blood and other works in English Göran Printz-Påhlson Edited by Robert Archambeau https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2011 Robert Archambeau; Foreword © 2011 Elinor Shaffer; ‘The Overall Wandering of Mirroring Mind’: Some Notes on Göran Printz-Påhlson © 2011 Lars-Håkan Svensson; Göran Printz-Påhlson’s original texts © 2011 Ulla Printz-Påhlson. Version 1.2. Minor edits made, May 2016. Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Göran Printz-Påhlson, Robert Archambeau (ed.), Letters of Blood. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0017 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www. openbookpublishers.com/product/86#copyright Further details about CC BY-NC-ND licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/ All the external links were active on 02/5/2016 unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume can be found at https://www. -

GRE Vocabulary

Table of Contents Introduction About Us What is Magoosh? Featured in Why Our Students Love Us How to Use Vocabulary Lists Timmy’s Vocabulary Lists Shirley’s Vocabulary Lists Timmy’s Triumph Takeway Making Words Stick: Memorizing GRE Vocabulary Come up with Clever (and Wacky) Associations Use It or Lose It Do Not Bite Off More Than You Can Chew Read to Be Surprised Takeaways Most Common GRE Words Top 10 GRE Words of 2012 Top 5 Basic GRE Words Common Words that Students Always Get Wrong Tricky “Easy” GRE Words with Multiple Meanings Commonly Confused Sets Interesting (and International) Word Origins Around the World French Words Eponyms Words with Strange Origins Themed Lists Vocab from Within People You Wouldn’t Want To Meet Religious Words Words from Political Scandals Money Matters: How Much Can You Spend? Money Matters: Can’t Spend it Fast Enough Money Matters: A Helping (or Thieving!) Hand Vocabulary from up on High Preposterous Prepositions Them’s Fighting Words gre.magoosh.com 1 Animal Mnemonics Webster’s Favorites “Occupy” Vocabulary Compound Words Halloween Vocabulary Talkative Words By the Letter A-Words C-Words Easily Confusable F-Words Vicious Pairs of V’s “X” words High-Difficulty Words Negation Words: Misleading Roots Difficult Words that the GRE Loves to Use Re- Doesn’t Always Mean Again GRE Vocabulary Books: Recommended Fiction and Non-Fiction The Best American Series The Classics Takeaway Vocabulary in Context: Articles from Magazines and Newspapers The Atlantic Monthly The New Yorker New York Times Book Review The New York Times Practice Questions Sentence Equivalence Text Completion Reading Comprehension GRE Vocabulary: Free Resources on the Internet gre.magoosh.com 2 Introduction This eBook is a compilation of the most popular Revised GRE vocabulary word list posts from the Magoosh GRE blog. -

Magooshgrevocabebook.Pdf

Updated 1/15/13 1 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 About Us ................................................................................................................... 4 What is Magoosh? ...................................................................................................... 4 Featured in ............................................................................................................. 4 Why Our Students Love Us ........................................................................................... 5 How to Use Vocabulary Lists ........................................................................................... 7 Timmy’s Vocabulary Lists ............................................................................................ 7 Shirley’s Vocabulary Lists ............................................................................................ 7 Timmy’s Triumph ...................................................................................................... 8 Takeway ................................................................................................................. 8 Making Words Stick: Memorizing GRE Vocabulary................................................................... 9 Come up with Clever (and Wacky) Associations .................................................................. 9 Use It or Lose It ....................................................................................................... -

Chapter 1: the Inter-Group and Present Scholarship……………………………………………………………………………………..57

YOUR BROTHERS, THE CHILDREN OF ISRAEL: ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN POLITICAL DISCCOURSE AND THE PROCESS OF BIBLICAL COMPOSITION A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Dustin Dale Nash January 2015 © 2015 Dustin Dale Nash YOUR BROTHERS, THE CHILDREN OF ISRAEL: ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN POLITICAL DISCOURSE AND THE PROCESS OF BIBLICAL COMPOSITION Dustin Dale Nash, Ph. D. Cornell University 2015 The Hebrew Bible contains seventeen isolated passages, scattered from Genesis to 2 brother”) to define an inter-group“) אח Samuel, that use the Hebrew term relationship between two or more Israelite tribes. For over a century, biblical scholars have interpreted this terminology as conceptually dependent on the birth narratives and genealogies of Gen 29-50, reiterated in stories and lists elsewhere in the biblical corpus. However, examination of the Bible’s depiction of the Israelite tribes as “brothers” outside these seventeen passages indicates that the static genealogical structure of the twelve-tribe system constitutes a late ideological framework that harmonizes dissonant descriptions of Israel as an association of “brother” tribes. Significantly, references to particular tribal groups as “brothers” in the Mari archives yields a new paradigm for understanding the origins of Israelite tribal “brotherhood” that sets aside this ideological structure. Additionally, it reveals the ways in which biblical scribes exploited particular terms and ideas as the fulcrums for editorial intervention in the Hebrew Bible’s composition. More specifically, close analysis of these Akkadian texts reveals the existence of an ancient Near Eastern political discourse of “brotherhood” that identified tribal groups as independent peer polities, bound together through obligations of reciprocal peaceful relations and supportive behavior. -

Andrew University

Andrew University ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES The Journal of the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary of Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan 49104-1 5OO, U.S.A. E &tors: Jerry Moon and John W. Reeve Managing E&tor: Karen K. Abrahamson Copy Editors: Leona G. Running and Madeline Johnston Book Review Editor John W. Reeve Book Review Manager: Erhard Gallos CircuIation Manager Erhard Gallos Managing Board Denis Forth, Dean of the Seminary, Chair,Jerry Moon, Secretary; Lyndon G. Furst, Dean of the School of Graduate Studies; Ron Knott, Director, Andrews University Press; Richard Choi; Ken Mulzac; and John W. Reeve. Communications: Phone: (269) 47 1-6023 Fax: (269) 471-6202 Electronic Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.auss.info A refereed journal, AiVDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARYSTUDIES provides a scholarly venue, within the context of biblical faith, for the presentation of research in the area of religious and biblical studies. AUSS publishes research articles, dissertation abstracts, and book reviews on the following topics: biblical archaeology and history of antiquity; Hebrew Bible; New Testament; church history of all periods; historical, biblical, and systematic and philosophical theology; ethics; history of reiigions; and missions. Selected research articles on ministry and Christian education may also be included. The opinions expressed in articles, book reviews, etc., are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the editors or of the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary. Subscription Information: UNI~RS~SEMINARYSTLIDIESis published in the Spring and the Autumn. The subscription rates for 2008 are as follows: Institutions Individuals Students/Retirees *Air mail rates available upon request Price for Single Copy is $12.00 in U.S.A. -

MFWPC04 Plus Postage

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 266 548 CS 209 690 AUTHOR Tompkins, Gail E.; Yaden, David B., Jr. TITLE Answering Students' Questions about Words. INSTITUTION ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading and Communication Skills, Urbana, Ill.; National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 86 CONTRACT 400-83-0025 NOTE 86p.; TRIP: Theory 6 Research into Practice. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 01879, $5.00 member, $6.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Information Analyses - ERIC Information Analysis Products (071) ;DRS PRICE MFWPC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Diachronic Linguistics; Elementary Education; *English; *Etymology; Language Patterns; Linguistic Borrowing; Linguistics; Orthographic Symbols; teaching Methods; Theory Practice Relationship ABSTRACT acknowledging that to study the development of a language is to study the history and culture of people and that English has been influenced by many geographic, political, economic, social, and linguistic forces, this booklet provides a ready reference for elementary and middle school/junior high school teachers confronted with students' questions about the characteristics of the language they speak and are learning to read and write. Since most questions are directed toward words and their spellings, the first section of the booklet emphasizes selected historical aspects of vocabulary growth and orthographic change. The second section of the booklet peesents exercises designed a-ound actual student questions, providing not only initial suggestions for vocabulary study activities, but also a rationale for the incongruities of English with an eye toward putting modern usage into a historical perspective. -

Download .Pdf Document

JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 1 what’s who? JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 2 JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 3 New edition, revised and enlarged what’s who? A Dictionary of things named after people and the people they are named after Roger Jones and Mike Ware JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 4 Copyright © 2010 Roger Jones and Mike Ware The moral right of the author has been asserted. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. Matador 5 Weir Road Kibworth Beauchamp Leicester LE8 0LQ, UK Tel: (+44) 116 279 2299 Fax: (+44) 116 279 2277 Email: [email protected] Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador ISBN 978 1848765 214 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 11pt Garamond by Troubador Publishing Ltd, Leicester, UK Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 5 This book is dedicated to all those who believe, with the authors, that there is no such thing as a useless fact. -

Draft the 100 Most Eminent Psychologists 1 the Published

Draft The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists 1 The published article can be found in Review of General Psychology, 2002, 6, 139-152. Copyright American Psychological Association. Running head: THE MOST EMINENT TWENTIETH CENTURY PSYCHOLOGISTS The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the Twentieth Century Steven J. Haggbloom Western Kentucky University Renee Warnick, Jason E. Warnick, Vinessa K. Jones, Gary L. Yarbrough, Tenea M. Russell, Chris M. Borecky, Reagan McGahhey, John L. Powell, III, Jamie Beavers, and Emmanuelle Monte Arkansas State University Address Correspondence to: Steven J. Haggbloom Department of Psychology 276 Tate Page Hall Western Kentucky University 1 Big Red Way Bowling Green, KY 42101 Draft The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists 2 email: [email protected] Phone: 270-745-4427 Abstract A rank-ordered list was constructed that reports the first 99 of the 100 most eminent psychologists of the twentieth century. Eminence was measured by scores on three quantitative variables and three qualitative variables. The quantitative variables were journal citation frequency, introductory psychology textbook citation frequency, and survey response frequency. The qualitative variables were National Academy of Science (NAS) membership, American Psychological Association (APA) President and/or recipient of the APA Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award, and surname used as an eponym. The qualitative variables were quantified and combined with the other three quantitative variables to produce a composite score that was then used to construct a rank-ordered list of the most eminent psychologists of the twentieth century. Draft The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists 3 The 100 Most-Eminent Psychologists of the Twentieth Century The discipline of psychology underwent a remarkable transformation during the twentieth century, a transformation that included a shift away from the European-influenced philosophical psychology of the late nineteenth century to the empirical, research-based, American-dominated psychology of today (Simonton, 1992). -

2010 Annual Report of the Governing Board of the School of Celtic S

B1 (b) SCHOOL OF CELTIC STUDIES ANNUAL REPORT (PART 2) 2010 Annual report of the Governing Board of the School of Celtic Studies for the year ending 31 December 2010. Bord Rialúcháin Scoil an Léinn Cheiltigh / Governing Board of the School of Celtic Studies (until 31 March 2010). Professor Anders Ahlqvist (Chairman); Professor Angela Bourke; Professor Máire Herbert; Professor Liam Mac Mathúna; Dr Eilís Ní Dheá; Professor Dónall Ó Baoill; Dr Nollaig Ó Muraíle; Professor Ruairí Ó hUiginn; Dr Katharine Simms; Professor Liam Breatnach; Professor Pádraig A. Breatnach (Director);Professor Fergus Kelly Bord Rialúcháin Scoil an Léinn Cheiltigh / Governing Board of the School of Celtic Studies (from 1 April 2010). The Board met twice during the year, on 10 June 2010 and 18 November 2010. Professor Anders Ahlqvist (Chairman); Professor Máire Herbert; Professor Jim McCloskey; Dr Uáitéar Mac Gearailt; Dr Eilís Ní Dhea; Dr Máire Ní Mhaonaigh; Professor Ailbhe Ó Corráin; Professor Ruairí Ó hUiginn; Dr Nollaig Ó Muraíle; Dr Katharine Simms; Professor Liam Breatnach; Professor Pádraig A. Breatnach (Director); Professor Fergus Kelly Foireann agus Scoláirí / Staff and Scholars Senior Professors: Pádraig A. Breatnach (Director), Liam Breatnach, Fergus Kelly Professors: Malachy McKenna, Pádraig Ó Macháin Assistant Professors: Aoibheann Nic Dhonnchadha, Michelle O Riordan (Publications Officer) Bibliographer: Alexandre Guilarte Dialectologist: Brian Ó Curnáin Bergin Fellows: Clodagh Downey, Roisin McLaughlin (to 8 May, 2010)IRCHSS Postdoctoral Fellowship)