From "Russian" to "Polish": Vilna-Wilno 1900-1925

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CES Open Forum Series 2019-2020

CES Open Forum Series 2019-2020 ASPIRATIONS OF IMPERIAL SPACE. THE COLONIAL PROJECT OF THE MARITIME AND COLONIAL LEAGUE IN INTERWAR POLAND by: Marta Grzechnik About the Series The Open Forum Paper Series is designed to present work in progress by current and former affiliates of the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies (CES) and to distribute papers presented at the Center’s seminars and conferences. Any opinions expressed in the papers are those of the authors and not of CES. Editors Grzegorz Ekiert and Andrew Martin Editorial Board Peter Hall, Roberto Stefan Foa, Alison Frank Johnson, Torben Iverson, Maya Jasanoff, Jytte Klausen, Michele Lamont, Mary D. Lewis, Michael Rosen, Vivien Schmidt, Kathleen Thelen, Daniel Ziblatt, Kathrin Zippel About the Author Marta Grzechnik is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Scandinavian Studies at the University of Gdańsk, Poland. She is a historian with a research interest in the twentieth-century history of the Baltic Sea region north-eastern Europe, regional his- tory, history of historiography, and history of colonialism. Abstract The paper discusses the case of an organization called Maritime and Colonial League, and its idea of colonial expansion that it attempted to promote in interwar Poland. It studies the colonial aspirations in two dimensions: the pragmatic and the symbolic. In the pragmatic dimension, acquiring colonies was supposed to remedy concrete economic and political problems. Overpopulation and resulting unemployment, as well as ethnic tensions, were to be alleviated by organized emigration of the surplus population; obstacles to the development of industries and international trade were to be removed thanks to direct access to raw resources and export markets overseas. -

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth As a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity*

Chapter 8 The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity* Satoshi Koyama Introduction The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) was one of the largest states in early modern Europe. In the second half of the sixteenth century, after the union of Lublin (1569), the Polish-Lithuanian state covered an area of 815,000 square kilometres. It attained its greatest extent (990,000 square kilometres) in the first half of the seventeenth century. On the European continent there were only two larger countries than Poland-Lithuania: the Grand Duchy of Moscow (c.5,400,000 square kilometres) and the European territories of the Ottoman Empire (840,000 square kilometres). Therefore the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the largest country in Latin-Christian Europe in the early modern period (Wyczański 1973: 17–8). In this paper I discuss the internal diversity of the Commonwealth in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and consider how such a huge territorial complex was politically organised and integrated. * This paper is a part of the results of the research which is grant-aided by the ‘Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research’ program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science in 2005–2007. - 137 - SATOSHI KOYAMA 1. The Internal Diversity of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Poland-Lithuania before the union of Lublin was a typical example of a composite monarchy in early modern Europe. ‘Composite state’ is the term used by H. G. Koenigsberger, who argued that most states in early modern Europe had been ‘composite states, including more than one country under the sovereignty of one ruler’ (Koenigsberger, 1978: 202). -

Prometejska Racja Stanu

POLITYKA WEWNĘTRZNA I bEZPIECZEńSTWO DOI: 10.12797/Poliarchia.02.2014.02.08 Bartosz ŚWIATŁOWSKI [email protected] PROMETEJSKA RACJA STANU ŹRÓDŁA I DZIEJE RUCHU PROMETEJSKIEGO W II Rzeczpospolite ABstract The Promethean reason of the state. The history of the Promethean move‑ ment in the Second Polish Republic Prometheism, which started to develop in 1921, after the Polish ‑Bolshevik Peace of Riga, was both an ideological and political project. The idea of liberating na‑ tions oppressed by the Soviet Union was accompanied by publishing activi‑ ties, institutional and community network. The article presents the genesis of Prometheism, its geopolitical and historical sources, political provenance of its main activists, evolution of the movement in the 1930s and the institutional di‑ mension of Polish Prometheists. The paper also discusses the most important views of the creators of the movement, including thoughts on Russian imperial‑ ism, solidarity with enslaved nations and the united fight for “our freedom and yours”, originating both in the sense of mission and the analysis of the Republic of Poland’s reason of state. The author focuses on two important elements of the movement – the realism of the political concept and the Promethean elite’s polit‑ ical thought about the state, the nation and the geopolitics of Eastern Europe. keywords prometheism, geopolitics, Europe, communism, sovereignty WSTĘP Ruch prometejski rozwijany od narodzin II Rzeczpospolitej, a ściślej od 1921 r., a więc od podpisania polsko ‑sowieckiego traktatu ryskiego1, był przedsięwzięciem zarówno 1 Traktat pokoju między Polską a Rosją i Ukrainą, podpisany w Rydze dnia 18 marca 1921 r., Dz. U. -

Lithuanian Voices

CHAPTER FIVE Lithuanian Voices 1. Lithuanian Letters in the U.S. The list of American works featuring Lithuanians is short; it apparently consists of three novels. However, for such a small nation, not a “global player” in Franzen’s words, three novels authored by Americans can be seen as sufficient and even impressive. After all, three American authors found Lithuanians interesting enough to make them the main characters of their works. Two of those works, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, became bestsellers and popularized the name of Lithuania in the U.S. and the world. The third work, Margaret Seebach’s That Man Donaleitis, although overlooked by critics and readers, nevertheless exists as a rare token of admiration for an obscure and oppressed people of the Russian empire. Many other small nations never made it to the pages of American texts. The best they could do was to present themselves to Americans in their own ethnic writing in English. However, the mere existence of such ethnic texts did not guarantee their success with the American audience. Ethnic groups from Eastern Europe for a long time presented little interest to Americans. As noted by Thomas Ferraro, autobiographical and biographical narratives of “immigrants from certain little-known places of Eastern Europe . did not attract much attention” (383). He mentions texts by a Czech, a Croatian, a Slovakian and a Pole written between 1904 and 1941, and explains the lack of attention to them from American public: “the groups they depict remained amorphous in the national imagination and did not seem to pose too much of a cultural threat” (383). -

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

WK 55 Ver 28.Indd

Barbara Werner Główny Specjalista ds. Ogrodów Historycznych Muzeum Łazienki Królewskie TULIPAN Marszałek Józef Piłsudski rośnie i zakwita na 100-lecie odzyskania niepodległości Od końca XVI wieku tulipany, które do Europy zachodniej, do Niderlandów przybyły z Turcji, na dobre zadomowiły się w europejskich ogrodach i nie sposób sobie wyobrazić wiosny bez ich obecności także w Łazienkach Królewskich. Z biegiem czasu z gatunków botanicznych powstała cała gama tysięcy odmian tulipana. Pojawiły się tulipany o różnym kształcie kieli- cha kwiatu, kolorze czy pokroju liści, o zróżnicowanym okresie kwitnienia – od wczesnej do późnej wiosny. Tulipany są obecnie niemalże wszędzie. Są symbolem wio- sny, radości i odradzającej się natury. Prezentują niemal całą gamę kolorów, od białych do prawie czarnych. Są popularne na całym świecie i nierzadko upamiętniają poprzez specjalną „cere- monię chrztu” wybrane wielkie postaci w historii poszczególnych krajów. Nowe odmiany tych niezwykłych, wybranych tulipanów rejestrowane są w Holandii przez Królewskie Powszechne To- warzystwo Uprawy Roślin Cebulowych (Koninklijke Algemeene Vereeniging voor Bloembollencultuur, KAVB) o ponad 150-letniej historii, z siedzibą w Hillegom. Jednym z tych nadzwyczajnych, jedynych tulipanów jest ochrzczony 9 maja tego roku w Teatrze Królewskim w Starej Oranżerii Tulipan „Marszałek Józef Piłsudski”. Jest to tulipan z grupy „Triumph”, o pojedynczym kwiecie, mocnej konstrukcji łodygi i liści. Jego kielich, o specjalnym kolorze karminu połączonego z odcieniem fi oletu i różu, na- wiązuje do kolorystyki elementów munduru Marszałka, czyli do aksamitnych wypustek przy kołnierzu o bardzo zbliżonym kolorze. Ten wytworny w kolorze kwiat ma jeden subtelny element. Na dnie kielicha tulipana, po jego rozkwitnięciu, znaj- dziemy złote wypełnienie, które możemy odczytać jako ukryte AZIENEK KRÓLEWSKICH Ł złote serca Marszałka… Od 9 maja 2018 roku pamięć o Marszałku Józefi e Piłsud- skim będzie trwała także w Ogrodzie Łazienek Królewskich, w rokrocznie zakwitającym wspaniałym, majowym tulipanie Jego Imienia. -

CENTRE for EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES University of Warsaw

CENTRE FOR EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES University of Warsaw The Centre’s mission is to prepare young, well-educated and skilled specialists in Eastern issues from Poland and other countries in the region, for the purposes of academia, the nation and public service... 1990-2015 1990-2015 ORIGINS In introducing the history of Eastern Studies in Poland – which the modern day Centre for EASTERN INSTITUTE IN WARSAW (1926-1939) East European Studies UW is rooted in – it is necessary to name at least two of the most im- portant Sovietological institutions during the inter-war period. Te Institute’s main task was ideological development of young people and propagating the ideas of the Promethean movement. Te Orientalist Youth Club (established by Włodzimierz Bączkowski and Władysław Pelc) played a signifcant part in the activation of young people, especially university students. Lectures and publishing activity were conducted. One of the practical tasks of the Institute was to prepare its students for the governmental and diplomatic service in the East. Te School of Eastern Studies operating as part of the Institute was regarded as the institution to provide a comprehensive training for specialists in Eastern issues and languages. Outstanding specialists in Eastern and Oriental studies shared their knowledge with the Insti- tute’s students, among them: Stanisław Siedlecki, Stanisław Korwin-Pawłowski, Ryochu Um- eda, Ayaz Ischaki, Witold Jabłoński, Hadżi Seraja Szapszał, Giorgi Nakashydze and others. Jan Kucharzewski (1876-1952), Cover of the “Wschód/Orient” chairman of the Eastern Institute journal published by the Eastern in Warsaw, author of the 7-volume Institute in Warsaw, editor-in- work “Od białego caratu do chief W. -

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski The Polish Police Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE NOVEMBER 17, 2016 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, April 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Jan Grabowski THE INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE, endowed by the William S. and Ina Levine Foundation of Phoenix, Arizona, enables the Center to bring a distinguished scholar to the Museum each year to conduct innovative research on the Holocaust and to disseminate this work to the American public. Wrong Memory Codes? The Polish “Blue” Police and Collaboration in the Holocaust In 2016, seventy-one years after the end of World War II, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs disseminated a long list of “wrong memory codes” (błędne kody pamięci), or expressions that “falsify the role of Poland during World War II” and that are to be reported to the nearest Polish diplomat for further action. Sadly—and not by chance—the list elaborated by the enterprising humanists at the Polish Foreign Ministry includes for the most part expressions linked to the Holocaust. On the long list of these “wrong memory codes,” which they aspire to expunge from historical narrative, one finds, among others: “Polish genocide,” “Polish war crimes,” “Polish mass murders,” “Polish internment camps,” “Polish work camps,” and—most important for the purposes of this text—“Polish participation in the Holocaust.” The issue of “wrong memory codes” will from time to time reappear in this study. -

Generate PDF of This Page

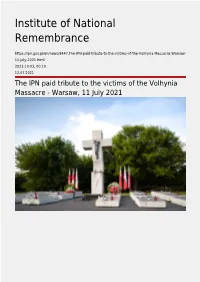

Institute of National Remembrance https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/8447,The-IPN-paid-tribute-to-the-victims-of-the-Volhynia-Massacre-Warsaw- 11-July-2021.html 2021-10-03, 00:10 12.07.2021 The IPN paid tribute to the victims of the Volhynia Massacre - Warsaw, 11 July 2021 On the 78th anniversary of "Bloody Sunday", flowers were laid to commemorate the victims of the Volhynia Massacre. The IPN was represented by its Deputy President, Krzysztof Szwagrzyk, Ph.D, D.Sc.and Adam Siwek, the Director of the IPN’s Office for Commemorating the Struggle and Martyrdom. The ceremonies commemorating the victims of the Volhynia Massacre took place by the monument to the Victims of Genocide, committed by Ukrainian nationalists on the citizens of the Second Polish Republic in the south-eastern provinces of Poland in the years 1942–1947 on 11 July 2021 at 8:00 p.m. The relatives of the victims, representatives of the authorities and organizations devoted to preserving the memory of the Borderlands took part in a mass for the murdered. After the national anthem and occasional speeches, flowers were placed under the plaques with the names of places from the pre-war provinces of the Second Polish Republic where the slaughter took place. Then, the participants of the ceremony went to the monument of the 27th Volhynian Infantry Division of the Home Army, where they laid wreaths. The IPN was represented by Deputy President Krzysztof Szwagrzyk, Ph.D, D.Sc. and Adam Siwek, the Director of the IPN’s Office for Commemorating the Struggle and Martyrdom. -

Towns in Poland” Series

holds the exclusive right to issue currency in the Republic of Poland. In addition to coins and notes for general circulation, TTownsowns inin PolandPoland the NBP issues collector coins and notes. Issuing collector items is an occasion to commemorate important historic figures and anniversaries, as well as to develop the interest of the public in Polish culture, science and tradition. Since 1996, the NBP has also been issuing occasional 2 złoty coins, In 2009, the NBP launched the issue struck in Nordic Gold, for general circulation. All coins and notes issued by the NBP of coins of the “Towns in Poland” series. are legal tender in Poland. The coin commemorating Warsaw Information on the issue schedule can be found at the www.nbp.pl/monety website. is the fifth one in the series. Collector coins issued by the NBP are sold exclusively at the Internet auctions held in the Kolekcjoner service at the following website: www.kolekcjoner.nbp.pl On 24 August 2010, the National Bank of Poland is putting into circulation a coin of the “Towns in Poland” series depicting Warsaw, with the face value of 2 złoty, struck in standard finish, in Nordic Gold. face value 2 zł • metal CuAl5Zn5Sn1 alloy •finish standard diameter 27.0 mm • weight 8.15 g • mintage (volume) 1,000,000 pcs Obverse: An image of the Eagle established as the State Emblem of the Republic of Poland. On the sides of the Eagle, the notation of the year of issue: 20-10. Below the Eagle, an inscription: ZŁ 2 ZŁ. In the rim, an inscription: RZECZPOSPOLITA POLSKA (Republic of Poland), preceded and followed by six pearls. -

Were the Baltic Lands a Small, Underdeveloped Province in a Far

3 Were the Baltic lands a small, underdeveloped province in a far corner of Europe, to which Germans, Swedes, Poles, and Russians brought religion, culture, and well-being and where no prerequisites for independence existed? Thus far the world extends, and this is the truth. Tacitus of the Baltic Lands He works like a Negro on a plantation or a Latvian for a German. Dostoyevsky The proto-Balts or early Baltic peoples began to arrive on the shores of the Baltic Sea nearly 4,000 years ago. At their greatest extent, they occupied an area some six times as large as that of the present Baltic peoples. Two thousand years ago, the Roman Tacitus wrote about the Aesti tribe on the shores of the #BMUJDBDDPSEJOHUPIJN JUTNFNCFSTHBUIFSFEBNCFSBOEXFSFOPUBTMB[ZBT many other peoples.1 In the area that presently is Latvia, grain was already cultivated around 3800 B.C.2 Archeologists say that agriculture did not reach southern Finland, only some 300 kilometers away, until the year 2500 B.C. About 900 AD Balts began establishing tribal realms. “Latvians” (there was no such nation yet) were a loose grouping of tribes or cultures governed by kings: Couronians (Kurshi), Latgallians, Selonians and Semigallians. The area which is known as -BUWJBUPEBZXBTBMTPPDDVQJFECZB'JOOP6HSJDUSJCF UIF-JWT XIPHSBEVBMMZ merged with the Balts. The peoples were further commingled in the wars which Estonian and Latvian tribes waged with one another for centuries.3 66 Backward and Undeveloped? To judge by findings at grave sites, the ancient inhabitants in the area of Latvia were a prosperous people, tall in build. -

Wroblewski Andrzej to the Ma

Courtesy of the Van Abbemuseum and Andrzej Wroblewski Foundation / www.andrzejwroblewski.pl ANDRZEJ WRÓBLEWSKI TO THE MARGIN AND BACK EDITED BY Magdalena Ziółkowska Van abbeMUseUM, EindHOVen, 2010 Courtesy of the Van Abbemuseum and Andrzej Wroblewski Foundation / www.andrzejwroblewski.pl Courtesy of the Van Abbemuseum and Andrzej Wroblewski Foundation / www.andrzejwroblewski.pl [1] Museum, 1956 Courtesy of the Van Abbemuseum and Andrzej Wroblewski Foundation / www.andrzejwroblewski.pl CONTENTS FILE UNDER SEMI-ACTIVE Charles Esche 9 TO THE MARGIN AND BACK Magdalena Ziółkowska 11 1 [Spring in January…] 15 COMMENTARY ON THE 1ST EXHIBITION OF MODERN ART Andrzej Wróblewski 18 REMarks ON MODERN ART Zbigniew Dłubak 24 STATEMENT ON THE 1ST EXHIBITION OF MODERN ART Andrzej Wróblewski 30 [A man does not consist…] 38 FROM STUDIES ON THE ŒUVRE OF Andrzej Wróblewski. THE PERIOD BEFORE 1949 Andrzej Kostołowski 42 2 [New realism] 69 ONE MORE WORD ON THE ART SCHOOLS Andrzej Wróblewski 72 [The artistic ideology of the group…] 75 Courtesy of the Van Abbemuseum and Andrzej Wroblewski Foundation / www.andrzejwroblewski.pl VISUAL ARTISTS IN SEARCH OF THE CORRECT PATH Andrzej Wróblewski 76 [Social contrasts — divisions] 80 [Satisfying specific social commissions…] 82 TO BE OR NOT TO BE IN THE POLISH UNITED WORKERS‘ PARTY Andrzej Wróblewski 86 CONFESSIONS OF A DISCREDITED ‘FoRMER COMMUNIST’ Andrzej Wróblewski 90 3 [We should settle the date for a MULTIARTISTIC EXHIBITION] 97 BODY AND MelanCHOLY. THE LATE WOrks OF Andrzej Wróblewski Joanna Kordjak-Piotrowska