Lithuanian Voices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lithuanian Writers and the Establishment During Late Socialism: the Writers Union As a Place for Conformism Or Escape Vilius Ivanauskas

LITHUANIAN HISTORICAL STUDIES 15 2010 ISSN 1392-2343 PP. 51–78 LITHUANIAN WRITERS AND THE EStabLISHMENT DURING LatE SOCIALISM: THE WRITERS UNION AS A PLACE FOR CONFORMISM OR ESCAPE Vilius Ivanauskas ABSTRACT This article analyses how the changes in the dominant attitude of local Soviet writers were encouraged, screened or restricted by the Writers Union [WU] through mechanisms of planning, control and even through measures of creating a secure daily environment. The author looks at the tensions and conflicts between writers of different generations, observing less ideology in the younger generation than in their predecessors since the development and dissemination of national images among the declared values of communism were increasing. The union as a system covered both aspects – conformism and the escape (manoeuvre). Though the WU had a strong mechanism of control, it managed to ensure for the writers such a model of adaptation where even those, who were subject to restrictions, had a possibility of remaining within the official structure, through certain compromises, while actually avoiding involvement in dissident activities or samizdat publishing. Introduction In August 1940 a group of Lithuanian intellectuals, most of whom were writers, went off to Moscow “to bring back Stalin’s Sunshine”, at the same time asking for Lithuania to be incorporated into the USSR. Forty eight years later in early June 1988 a few members of the local literary elite joined the initial Sąjūdis Group and from thenceforth stood in the vanguard of the National Revival. These two historic moments, witnessing two contrary breaking points in history, when Lithuanian writers were active participants in events, naturally give rise to the question of how the status and role of writers and their relationship with the Soviet regime changed. -

Lithuanian Literature in 1918–1940: the Dynamics of Influences and Originality

340 INTERLITT ERA RIA 2018, 23/2: 340–353 VANAGAITĖ Lithuanian Literature in 1918–1940: The Dynamics of Influences and Originality GITANA VANAGAITĖ Abstract. Lithuanian independence (1918–1940), which lasted for twenty- two years, and its symbolic center, the provisional capital Kaunas, have been very important for the country’s political, social, and cultural identity. In 1918, changes in the social, economic, and political status of an individual as well as transformations in the literary field followed the change of the political system. In what ways the relationship between the center and the periphery and the spheres of literary influences were altered by the new forms of life? Lithuania, the former geographic periphery of tsarist Russia, after the change of the political system became a geographical and cultural periphery of Europe. Nevertheless, political freedom provided an opportunity to use the dichotomy of center-periphery creatively. Lithuanian writers, who suddenly found them- selves living in Europe with old cultural traditions, tried to overcome the insignificance of their own literature, its shallow themes and problems by “borrowing” ideas and ways to express them. In fact, the imitation was not mechanical, so the new influences enabled writers to expand significantly the themes and forms of Lithuanian literature. The article examines the development of new cultural centers in inde- pendent Lithuania. It also discusses the avant-garde movement which emerged under the influence of Russian futurists and German expressionists. In addition, it focuses on individual authors, such as Antanas Vaičiulaitis, Kazys Binkis and Petras Cvirka, and the influence that affected their works. Keywords: center; periphery; literary influence; host culture Center and Periphery in Literature The word periphery translated from the Latin (peripherīa) means “a circle.” In turn, this Latin word is related to two Greek words, perí, which means “around,” and pherein – “to carry”. -

Darius Staliūnas HISTORIOGRAPHY of the LITHUANIAN NATIONAL

Darius Staliūnas HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE LITHUANIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT CHANGING PARADIGMS The beginning of Lithuanian national historiography and the topic of ‘National Revival’ The Lithuanian historical narrative was formed during the nineteenth century as a component part of a newly developing Lithuanian national discourse. One of the most important and most difficult tasks facing the construction of a modern Lithuanian identity was how to separate it from the Polish identity (as well as from its Russian counterpart, even though Russianness was not regarded as being so parlous for the ‘purification’ of national identity). It therefore comes as no surprise that Lithuanians construed their concept of history as an alternative to the Polish construction (and to a lesser degree to the Russian version). Most nineteenth-century Polish political movements, including schools of history, did not regard the Lithuanians as having any independent political future and so it is not surprising that they were inclined first and foremost to stress the benefits of Polish culture and civilisation in Lithuania’s past. The Lithuanians had no other option than using their authentic ethnic culture as a counterweight to Polish civilisation. Conceiving Lithuanian identity as primarily ethno-cultural values, a concept of Lithuanian history was construed accordingly. The history of Lithuania was considered to be Darius Staliūnas, ‘Historiography of the Lithuanian national movement. Changing paradigms’, in: Studies on National Movements, 1 (2013) pp. 160-182. http://snm.nise.eu Studies on National Movements, 1 (2013) | ARTICLES the history of (ethnic) Lithuanians. Topics connected with ‘national revival’ have clearly dominated in texts devoted to nineteenth-century history. -

Were the Baltic Lands a Small, Underdeveloped Province in a Far

3 Were the Baltic lands a small, underdeveloped province in a far corner of Europe, to which Germans, Swedes, Poles, and Russians brought religion, culture, and well-being and where no prerequisites for independence existed? Thus far the world extends, and this is the truth. Tacitus of the Baltic Lands He works like a Negro on a plantation or a Latvian for a German. Dostoyevsky The proto-Balts or early Baltic peoples began to arrive on the shores of the Baltic Sea nearly 4,000 years ago. At their greatest extent, they occupied an area some six times as large as that of the present Baltic peoples. Two thousand years ago, the Roman Tacitus wrote about the Aesti tribe on the shores of the #BMUJDBDDPSEJOHUPIJN JUTNFNCFSTHBUIFSFEBNCFSBOEXFSFOPUBTMB[ZBT many other peoples.1 In the area that presently is Latvia, grain was already cultivated around 3800 B.C.2 Archeologists say that agriculture did not reach southern Finland, only some 300 kilometers away, until the year 2500 B.C. About 900 AD Balts began establishing tribal realms. “Latvians” (there was no such nation yet) were a loose grouping of tribes or cultures governed by kings: Couronians (Kurshi), Latgallians, Selonians and Semigallians. The area which is known as -BUWJBUPEBZXBTBMTPPDDVQJFECZB'JOOP6HSJDUSJCF UIF-JWT XIPHSBEVBMMZ merged with the Balts. The peoples were further commingled in the wars which Estonian and Latvian tribes waged with one another for centuries.3 66 Backward and Undeveloped? To judge by findings at grave sites, the ancient inhabitants in the area of Latvia were a prosperous people, tall in build. -

From "Russian" to "Polish": Vilna-Wilno 1900-1925

FROM “RUSSIAN” TO “POLISH”: Vilna-Wilno 1900-1925 Theodore R. Weeks Southern Illinois University at Carbondale The National Council for Eurasian and East European Research 910 17th Street, N.W. Suite 300 Washington, D.C. 20006 TITLE VIII PROGRAM Project Information* Principal Investigator: Theodore R. Weeks Council Contract Number: 819-06g Date: June 4, 2004 Copyright Information Scholars retain the copyright on works they submit to NCEEER. However, NCEEER possesses the right to duplicate and disseminate such products, in written and electronic form, as follows: (a) for its internal use; (b) to the U.S. Government for its internal use or for dissemination to officials of foreign governments; and (c) for dissemination in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of the U.S. government that grants the public access to documents held by the U.S. government. Additionally, NCEEER has a royalty-free license to distribute and disseminate papers submitted under the terms of its agreements to the general public, in furtherance of academic research, scholarship, and the advancement of general knowledge, on a non-profit basis. All papers distributed or disseminated shall bear notice of copyright. Neither NCEEER, nor the U.S. Government, nor any recipient of a Contract product may use it for commercial sale. * The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract or grant funds provided by the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, funds which were made available by the U.S. Department of State under Title VIII (The Soviet-East European Research and Training Act of 1983, as amended). -

Klaipedos Kr Dainos.Indd

Singing tradition of the Klaipėda region preserved in Lithuania and in the émigré communities In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it was the Lithuanian songs of East Prussia that opened the way for Lithuanian language and culture into Western Europe. The elegiac folk poetry, with characteristically straightforward structure and plain subject matter, fascinated the enlightened minds of artists and scholars, kindling their imagination and providing inspiration for their own creative work. Certain ideas that originated in the Age of Enlightenment and gained currency in Western Europe, coupled with the nascent concern about the newly discovered yet already vanishing layer of traditional culture, lent an important impetus for preservation of that obsolescent culture. It was then that the Lithuanian songs were first recorded, published and researched. The network of Prussian clergymen who were the first collectors of folklore formed around Liudvikas Rėza (Ludwig Rhesa) (1776‒1840), a professor at the University of Königsberg, amassed a priceless repository of Lithuanian non-material culture, which kept growing by the effort of countless devout enthusiasts during the coming two hundred years. The present collection of Songs and Music from the Klaipėda Region is yet another contribution to this ever expanding repository. At long last we will have an opportunity to hear the real sound of what many of us have only known in the form of written down verses, notated melodies, and interpretations thereof. As a matter of fact, no sound recordings of authentic Prussian Lithuanian songs or instrumental music have been published in Lithuania in the course of the 20th century. On the other hand, there was no apparent lack of valuable materials preserved at folklore archives and informants who could have sung Lithuanian folk songs for the compilers of sound anthologies in the middle of 26 the 20th century. -

Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania Resolution No Xiv

SEIMAS OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA RESOLUTION NO XIV-72 ON THE PROGRAMME OF THE EIGHTEENTH GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA 11 December 2020 Vilnius In pursuance of Articles 67(7) and 92(5) of the Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania and having considered the Programme of the Eighteenth Government of the Republic of Lithuania, the Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania, has resolved: Article 1. To approve the programme of the eighteenth Government of the Republic of Lithuania presented by Prime Minister of the Republic of Lithuania Ingrida Šimonytė (as appended). SPEAKER OF THE SEIMAS Viktorija Čmilytė-Nielsen APPROVED by Resolution No XIV-72 of the Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania of 11 December 2020 PROGRAMME OF THE EIGHTEENTH GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1. As a result of the world-wide pandemic, climate change, globalisation, ageing population and technological advance, Lithuania and the entire world have been changing faster than ever before. However, these global changes have led not only to uncertainty and anxiety about the future but also to a greater sense of togetherness and growing trust in each other and in the state, thus offering hope for a better future. 2. This year, we have celebrated the thirtieth anniversary of the restoration of Lithuania’s independence. The state that we have all longed for and taken part in its rebuilding has reached its maturity. The time has come for mature political culture and mature decisions too. The time has come for securing what the Lithuanian society has always held high: openness, responsibility, equal treatment and respect for all. -

Lithuania Guidebook

LITHUANIA PREFACE What a tiny drop of amber is my country, a transparent golden crystal by the sea. -S. Neris Lithuania, a small and beautiful country on the coast of the Baltic Sea, has often inspired artists. From poets to amber jewelers, painters to musicians, and composers to basketball champions — Lithuania has them all. Ancient legends and modern ideas coexist in this green and vibrant land. Lithuania is strategically located as the eastern boundary of the European Union with the Commonwealth of Independent States. It sits astride both sea and land routes connecting North to South and East to West. The uniqueness of its location is revealed in the variety of architecture, history, art, folk tales, local crafts, and even the restaurants of the capital city, Vilnius. Lithuania was the last European country to embrace Roman Catholicism and has one of the oldest living languages on earth. Foreign and local investment is modernizing the face of the country, but the diverse cultural life still includes folk song festivals, outdoor markets, and mid- summer celebrations as well as opera, ballet and drama. This blend of traditional with a strong desire to become part of the new community of nations in Europe makes Lithuania a truly vibrant and exciting place to live. Occasionally contradictory, Lithuania is always interesting. You will sense the history around you and see history in the making as you enjoy a stay in this unique and unforgettable country. AREA, GEOGRAPHY, AND CLIMATE Lithuania, covering an area of 26,173 square miles, is the largest of the three Baltic States, slightly larger than West Virginia. -

The Revival of Lithuanian Polyphonic Sutartinės Songs in the Late 20Th and Early 21St Century Daiva Račiūnaitė-Vyčinienė

The Revival of Lithuanian Polyphonic Sutartinės Songs in the Late 20th and Early 21st Century Daiva Račiūnaitė-Vyčinienė Introduction The ‘Neo-Folklore movement’ (in Lithuania, In contemporary ethnomusicology, attention is folkloro judėjimas, folkloro ansamblių judėjimas; increasingly paid to the defi nition of the terms in Latvia, folkloras absambļu kustība; in Estonia, ‘tradition’ and ‘innovation’. These defi nitions folklooriliikumine) is the term used in the Baltic include stability and mobility; repetition and contries (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) to denote creativity; ‘fi rst’ and ‘second existence’1 and similar the increased interest in folklore tradition during concepts, and how these phenomena relate the 1970s and 80s. The term also ‘describes the to folklore traditions. Most of today’s musical practical forms of actualizing folklore in daily traditions can be described as ‘revival’. This term life and in the expressions of amateur art that is used widely yet ambiguously in research in have accompanied the spiritual awakening of the English language.2 The word is applied to the people and their fi ght for the restoration of the phenomena of revitalisation, recreation, independence at beginning of the 1990s’ (Klotiņš innovation, and transformation, these terms often 2002: 107). In Soviet times, the Lithuanian folklore being used synonymously and interchangeably.3 ensemble movement,5 one among thousands of its Nevertheless, there are some ethnomusicologists kind, was a form of resistance to denationalisation who take a purist approach, adhering to the and to other Soviet ideologies. Without this original meanings of these terms. The Swedish ethnic, cultural union there would not have been ethnomusicologist Ingrid Åkesson describes a Singing Revolution.6 three basic concepts that apply to the processes This movement encompassed a variety of of change in folklore, each with its own shade of folklore genres and styles, refl ecting the general meaning: ‘recreation’, ‘reshaping’/‘transformation’, revival and reinvigoration of folklore. -

1. What This Book Hopes to Do “Lithuania Is Becoming a Symbol of Horror in America”; “The American Author Explains Why He

INTRODUCTION 1. What This Book Hopes to Do “Lithuania is becoming a symbol of horror in America”; “The American author explains why he portrayed our country as hell in his novel”; “Lithuanian anger on Thanksgiving Day,” shouted the headlines of the leading Lithuanian daily Lietuvos rytas on November 24, 2001 (Alksninis 1). On Thanksgiving Day, 2001, the American author Jonathan Franzen did not receive thanks from Lithuanians. His recent novel The Corrections (2001), a National Book Award winner and a U.S. national bestseller, presents an image of contemporary Lithuania that Lithuanians find “negative,” “grotesque,” and “caricature-like” (ýesnienơ). The Lithuanian Ambassador in Washington, Vygaudas Ušackas, sent letters of protest to the author and Farrar, Straus and Giroux, his publishers. Franzen responded by expressing his regret that the “fruit of his imagination” was perceived by Lithuanians as “likely to have negative consequences” (Draugas). The writer believes that a “majority” of his readers will understand that The Corrections belongs to the genre of fiction, not journalism (Draugas). While acknowledging Franzen’s right to imagination, I think he underestimates the power of fiction in forging images and stereotypes in the public imagination, particularly in fiction that portrays countries as obscure to Americans as Lithuania. Almost a hundred-year gap separates Franzen’s novel from the first American bestseller that featured Lithuanians, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (1906). Both writers portray Lithuanian arrivals in the United States. Sinclair presents an immigrant of the beginning of the twentieth century, Jurgis Rudkus, and Franzen a trans-national migrant of the end of the twentieth century, Gitanas Miseviþius. -

The Microcosm Within the Macrocosm: How the Literature of a Small Diaspora Fits Within the Context of Global Literature

The Microcosm within the Macrocosm: How the Literature of a Small Diaspora Fits Within the Context of Global Literature Laima Vincė Sruoginis, Vilnius University, Lithuania The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2018 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The twentieth century was a century of global powers: the Soviet Union, the United States. Now China is on the rise. Where do these superpowers and major language groups leave small countries and their identities? Whether we are ready for it or not, humanity is shifting away from tribal identities towards a global identity that is yet to be defined. This process began with massive shifts of refugees during World War II and continues today with refugees internationally displaced by economic deprivation, environmental disasters, and war. As population shifts continue, humanity has no other option but to adapt. These processes are reflected in contemporary global literature. A life straddling two or more cultures and languages becomes second nature to those born into an ethnic diaspora. The children and grandchildren of refugees learn from a young age to hold two or three cultural perspectives and languages in balance. Writers who emerge from these diasporas have a unique perspective. Since the postwar era Lithuanian diasporas have existed in North America, South America, Australia, Europe, and now Asia. In American literature several generations of descendants of Lithuanian war refugees have emerged who write in English about their nation's experience. Most notable is Ruta Sepetys, whose novel, Between Shades of Gray, has been published in 41 countries and translated into 23 languages, including Japanese and Chinese. This paper will examine how the literature of one nation's diaspora fits within the context of global literature. -

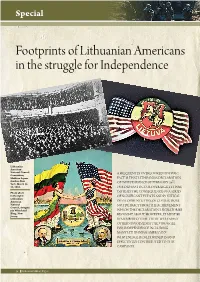

Lithuanian Independence Movement That Struggle Did Not Succeed, It Energized the Only Gradually Evolved in the Homeland

Special Footprints of Lithuanian Americans in the struggle for Independence Lithuanian American National Council A FREQUENTLY OVERLOOKED HISTORIC Convention, Madison Square FACT IS THAT LITHUANIA’S DECLARATION Garden, New TH York, March 13- OF INDEPENDENCE OF FEBRUARY 16 , 14, 1918. 1918, DID NOT OCCUR OVERNIGHT. IT WAS, Photo above INSTEAD, THE CONSEQUENCE OF A SERIES in the right: OF SIGNIFICANT EVENTS AND POLITICAL Lithuanian American DEVELOPMENTS. THIS, OF COURSE, DOES National NOT DETRACT FROM THE ACHIEVEMENT Council, delegate pin Whitehead WHICH THE DECLARATION’S SIGNATORIES Hoag, New BROUGHT ABOUT. HOWEVER, IT MUST BE Jersey. REMEMBERED THAT THERE WERE MANY OTHERS INVOLVED IN THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE INCLUDING MANY LITHUANIAN AMERICANS WHO ENERGETICALLY JOINED IN AND EFFECTIVELY CONTRIBUTED TO THIS CAMPAIGN. 16 Lithuanian Military Digest Special THE NATIONAL AWAKENING Independence — complete Lithuanian politi- t is generally agreed that the Lithuanian cal sovereignty a year before it was declared in National Awakening of the late 19th centu- Lithuania! ry and the resultant Lithuanian Indepen- Idence movement stemmed from the Polish- A LITHUANIAN MONARCHY? Lithuanian Insurrection of 1863–1864. While The Lithuanian independence movement that struggle did not succeed, it energized the only gradually evolved in the homeland. Initial- nation to continue its efforts to free itself from ly, the leaders of the movement merely sought Czarist rule. The consequent brutal suppres- some modicum of political autonomy, some sion of this insurrection led to an even greater accommodation within the framework of Czar- resolve to resist tyranny. The Russian regime ist Russian Empire. In 1905 the Russians were outlawed the publishing of books in the Lithu- routed in the ill-fated Russo-Japanese War.