The Forum, Vol. 5, Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lithuanian Voices

CHAPTER FIVE Lithuanian Voices 1. Lithuanian Letters in the U.S. The list of American works featuring Lithuanians is short; it apparently consists of three novels. However, for such a small nation, not a “global player” in Franzen’s words, three novels authored by Americans can be seen as sufficient and even impressive. After all, three American authors found Lithuanians interesting enough to make them the main characters of their works. Two of those works, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, became bestsellers and popularized the name of Lithuania in the U.S. and the world. The third work, Margaret Seebach’s That Man Donaleitis, although overlooked by critics and readers, nevertheless exists as a rare token of admiration for an obscure and oppressed people of the Russian empire. Many other small nations never made it to the pages of American texts. The best they could do was to present themselves to Americans in their own ethnic writing in English. However, the mere existence of such ethnic texts did not guarantee their success with the American audience. Ethnic groups from Eastern Europe for a long time presented little interest to Americans. As noted by Thomas Ferraro, autobiographical and biographical narratives of “immigrants from certain little-known places of Eastern Europe . did not attract much attention” (383). He mentions texts by a Czech, a Croatian, a Slovakian and a Pole written between 1904 and 1941, and explains the lack of attention to them from American public: “the groups they depict remained amorphous in the national imagination and did not seem to pose too much of a cultural threat” (383). -

It Started Friendship

2019 OCTOBER PHL declares Polio Outbreak The last known case from a wild strain of the virus in the Philippines was in 1993. The wild poliovirus type 2 was declared globally eradicated in 2015. MANILA, Philippines -- Philip- pine health officials declared a polio outbreak in the coun- try on September 19, nearly two decades after the World Health Organization declared it to be free of the highly con- tagious and potentially dead- ly disease. Health Secretary Francisco Duque III said at a news conference that authori- ties have confirmed at least one case of polio in a 3-year-old girl in southern Lanao del Sur province and detected the polio virus in sewage in Manila and in waterways in the southern Davao region. Those findings are enough to POLIO continued on page 11 Enrique Manila may be a & Terror Target It’s more populated and LIZA GIL cause more harm and victims in terrorizing the Soberano government MANILA - A Deputy Speaker in the It Started House of Representatives thinks it’s like- ly that terror groups might target Metro Manila next after launching a series of bombings in Mindanao. With As such, Surigao del Sur 2nd district Rep. Johnny Pimentel said that law en- forcement authorities should be on their toes regarding a possible spillover of the attacks from down south, adding it would Friendship be costly in terms of human life. “It is highly possible that their next MANILA TERROR continued on page 9 Spotlight ANTI-VACCINATION CAUSE POLIO COMEBACK Au Bon Vivant, 1970’S Coco Martin to continue Ang probinsiyano More Alden Richards is Truly Gifted Ivana Alawi, not an Escort Service Women Julia Montes to come home soon OFW’s Sharon-Gabby Movie is still Possible? Kylie Maxine Spitting issue is Gimmick? than Kim Molina Happy sa Jowable box-office LizQuen, KathNiel has new Teleserye Men PAGE 8 1 1 2 2 2016. -

MEMOIRS of a GEISHA John Williams, Composer Dreamworks SKG Ian Bryce, Lucy Fisher, Steven Spielberg, Douglas Wick, Prods

KENNETH WANNBERG MUSIC EDITOR MEMOIRS OF A GEISHA John Williams, Composer DreamWorks SKG Ian Bryce, Lucy Fisher, Steven Spielberg, Douglas Wick, prods. Rob Marshall, dir. STAR WARS: EPISODE 3-REVENGE John Williams, Composer OF THE SITH Lucas Film Rick McCallum, prod. George Lucas, dir. THE TERMINAL John Williams, Composer DreamWorks SKG Laurie MacDonald, Walter Parkes, Steven Spielberg, prods. Steven Spielberg, dir. HARRY POTTER AND THE PRISONER John Williams, Composer OF AZKABAN Warner Bros. David Heyman, prod. Alfonso Cuaron, dir. CATCH ME IF YOU CAN John Williams, Composer DreamWorks SKG Walter Parkes, Steven Spielberg, prods. Steven Spielberg, dir. MINORITY REPORT John Williams, Composer 20th Century Fox Walter Parkes, Jan De Bont, Gerald Molen, Bonnie Curtis, prods. Steven Spielberg, dir. STAR WARS: EPISODE 2-ATTACK OF John Williams, Composer THE CLONES LucasFilm / JAK Productions Rick McCallum, prod. George Lucas, dir. HARRY POTTER AND THE John Williams, Composer SORCERER’S STONE Warner Bros. David Heyman, prod. Chris Columbus, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 KENNETH WANNBERG MUSIC EDITOR A.I.: ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE John Williams, Composer DreamWorks / Warner Bros. Kathleen Kennedy, Bonnie Curtis, Steven Spielberg, prods. Steven Spielberg, dir. THE PATRIOT John Williams, Composer Sony Pictures Dean Devlin, Mark Gordon (II), Gary Levinson, prods. Roland Emmerich, dir. ANGELA’S ASHES John Williams, Composer Paramount Pictures David Brown, Alan Parker, Scott Rudin, prods. Alan Parker, dir. STAR WARS: THE PHANTOM John Williams, Composer MENACE Lucas Film Rick McCallum, prod. George Lucas, dir. STEPMOM John Williams, Composer Sony Pictures Wendy Finerman, Mark Radcliffe, Michael Barnathan, prods. Chris Columbus, dir. SAVING PRIVATE RYAN John Williams, Composer DreamWorks SKG Steven Spielberg, Mark Gordon, Ian Bryce, Gary Levinson, prods. -

Asians & Pacific Islanders Across 1300 Popular Films (2021)

The Prevalence and Portrayal of Asian and Pacific Islanders across 1,300 Popular Films Dr. Nancy Wang Yuen, Dr. Stacy L. Smith, Dr. Katherine Pieper, Marc Choueiti, Kevin Yao & Dana Dinh with assistance from Connie Deng Wendy Liu Erin Ewalt Annaliese Schauer Stacy Gunarian Seeret Singh Eddie Jang Annie Nguyen Chanel Kaleo Brandon Tam Gloria Lee Grace Zhu May 2021 ASIANS & PACIFIC ISLANDERS ACROSS , POPULAR FILMS DR. NANCY WANG YUEN, DR. STACY L. SMITH & ANNENBERG INCLUSION INITIATIVE @NancyWangYuen @Inclusionists API CHARACTERS ARE ABSENT IN POPULAR FILMS API speaking characters across 1,300 top movies, 2007-2019, in percentages 9.6 Percentage of 8.4 API characters overall 5.9% 7.5 7.2 5.6 5.8 5.1 5.2 5.1 4.9 4.9 4.7 Ratio of API males to API females 3.5 1.7 : 1 Total number of speaking characters 51,159 ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ A total of 3,034 API speaking characters appeared across 1,300 films API LEADS/CO LEADS ARE RARE IN FILM Of the 1,300 top films from 2007-2019... And of those 44 films*... Films had an Asian lead/co lead Films Depicted an API Lead 29 or Co Lead 44 Films had a Native Hawaiian/Pacific 21 Islander lead/co lead *Excludes films w/ensemble leads OF THE 44 FILMS OF THE 44 FILMS OF THE 44 FILMS OF THE 44 FILMS WITH API WITH API WITH API WITH API LEADS/CO LEADS LEADS/CO LEADS LEADS/CO LEADS LEADS/CO LEADS 6 0 0 14 WERE WERE WOMEN WERE WERE GIRLS/WOMEN 40+YEARS OF AGE LGBTQ DWAYNE JOHNSON © ANNENBERG INCLUSION INITIATIVE TOP FILMS CONSISTENTLY LACK API LEADS/CO LEADS Of the individual lead/co leads across 1,300 top-grossing films.. -

See 2019 Festival Program for Review

Celebrating 10 years in the Media Capital of the World September 5th - 9th September 5, 2018 Dear Friends: On behalf of the City of Los Angeles, welcome to the 2018 Burbank International Film Festival. Since 2009, the Burbank International Film Festival has promoted up-and-coming filmmakers from around the world by providing a gateway to expand their careers in the entertainment industry. I applaud the efforts of the Festival’s organizers and sponsors to create an event that generates an appreciation of storytelling through film. Thank you for your contributions to the vibrant artistic culture of Los Angeles. Congratulations to all the Industry Icon honorees. I send my best wishes for what is sure to be a successful and memorable event. Sincerely, ERIC GARCETTI Mayor September 5, 2018 Dear Friends, Welcome to the 2018 Burbank International Film Festival as we celebrate 10 successful years in "The Media Capitol of the World." The Burbank International Film Festival has given a platform to promising filmmakers, sharing their hard work with an eager audience and providing the means to expand their budding careers. As champions of independent filmmaking, the Festival organizers represent true benefactors to the colorful Los Angeles arts scene that we all enjoy. Congratulations to all the Festival honorees at this pivotal point in their careers. We appreciate your dedication and the contribution it makes to our arts culture. Sincerely, ANTHONY J. PORTANTINO Senator 25th Senate District Board of Directors Jeff Rector President / Festival Director Jeff is an award-winning filmmaker and working actor. His feature film “Revamped” which he wrote, directed and produced, is currently being distributed worldwide. -

Paul Scanlan

*"$"$1##(*'"&%,'%$(2 )4()'+$%'$%*'$, %#&$. %$0 $)4()'(%$,4'""')%.2 $$%%$'&'($)() &%,'%$(#%')$)$ 2 ,!%(#$1''%()%&'%+'())'*(,$.%*('#$ ,%'+(%$'(2$#$(,%'(+&%,'2 +$#)1 $4))#)%'0*))*)#)%$ %.'$2 $%) )#)%'#0*)+#(%#$.)$()%'#%*)2 +$1#%()*$"+")$)%#%*))$ ())$+'(&&%$)(2 (')%$(%$4)(&&%$)0(#$)%$%($4)(&&%$)2 %'"$1 ')(#%#$)(,)%$%*(2 ,!%(#$1%(()%'(+"&*())'%*$'2.+"&*( ,$,,'*"")(%%"2).%*+%$(%".)%')$-)$)2 +$1$$%,'$)(%*').'%'+'#%'&%&",""!$%,,) 4+ ",.(!$%,$,(.%*+#&%((".(%()%""2 )$ 1 ,()%")%+,,%'(*()'4,&%&"')%$)2 +%*(". "%+.%*""2%*4'""$(2 ,!%(#$1)$ ()!$(+(%$0&")#$(*"(0( &)*'(,)$)()')'(,)-)'%'$'.")(2(($+'$ -)))')$,$)$ ')"!$)'2%*+)%)$!%*))4( .%$+"')(2)4("!#&%,'#$)2 (#*("+$)%(*$+'(($ $%$(%0,(*#$((&')%))' *()"!)%(')'(2 *"$"$1$%))$()))$4($!$%,$)%(.()),)')&%,'– 2 6 $$(%$1222%#(')'(&%$(").$))4(–))4((%#)$"!")'"".0, )$!%*)),)) %$2))),'%"")+0,4''%*&24'%+' 680555&%&"$,4+%))(#/$&%,'*))'4("(%)(#/$ '(&%$(").))%#(,))2 )$ 1 4+$)"*!()#$$),%'"*( 4+'$(2$"*!.)% +,%$'*",2 *"$"$1"%)%&%&"""#)'!,$%')""#!(&'%%*' $')%$2$ "+)),%"')".2 )$ 1!(&',(&')).%%0)%%2 "'!'1$!.%*0)$2$!.%*%'('$)$'",%'"(%.%*' #$)%$,)*(2.,)!)+''%'$%)',%'(222 )$ 1-"(%'3 2 7 .%'%'6Legion M is the world’s first fan8(0''-+-"'&'-(&)'27 ''",('6What we’re doing with Legion M has never been possible before. >? .%'%'4 ''",(' "('(8(.'+, .%'%'6/+7 ''",('6-!"'$-!-''-+-"'&'-(&)'2(0'2',",--+-!'(' (0'2%%-+-7 .%'%'6And so we’re funding "%&,',!(0,')+(#-,7 >? 6 .%'%'6Collectively, as a community. And when we’re successful, share"'-!+0+7 (.$'(0"' )+-( "('50!-!+2(."'/,-(+'(-5","' -

Starlog Magazine

—' 'IV \ j, ! t ''timmffy* STAR WARS Christopher Lee vs. Yoda! REIGN OF FIRE Total future dragon war! EIGHT LEGGED FREAKS Spider nightmare fun! Discover the power af the dark side with the Star Wars Trading Card Game. The tempting new Sith Rising card set lets you crush your enemies with weapons, ships, and villains from The Star Wars saga. Or refuse to give in to your anger, and thwart those who would tyrannize the galaxy. Once you learn to control the Force, take your battle into a new arena the Star Wars TCG League. You will embark on Jedi training, and even a Sith Lord can't stop you from earning exclusive promo cards and learning Jedi secrets. Rules only available in: Two-Player Starter Game Advanced Starter Decks Dfficial Star Wars Web Site www.starwars.CDm © 2002 Lucasfilm Ltd. & TM. All rights resen/ed. Wizards of the Coast is a registered trademark of Wizards of the Coast, Inc. BACK IN BLACK Barry Sonnenfeld directs the scum of the universe again FILING MINORITY REPORT i { Producer Bonnie Curtis takes a reel view of future paranoia TOM CRUISE ON THE RUN He's desperate to prove he's an innocent guilty man SECRETS OF FARSCAPE Pssst! David Kemper reveals all—or not—on the series' new year MISSION: ODYSSEY 5 Only creator Manny Coto knows why the world ends MY PET KILLER ALIEN watercolor Lilo's world with thoughts of Elvis & Stitch WEBS OF SPIDER DEATH Producer Dean Devlin Preeds Eight Legged Freaks HERE THERE BE DRAGONS Director RoP Bowman readies Earth for a Reign of Fire CHRISTOPHER LEE SPEAKS Now, the legend in starlight can talk aPout Star Wars MIND READER Anthony Michael Hall predicts success for The Dead Zone NIGHT, ARES Not content with munching GOOD SWEET STARLOG's indicia The late Kevin Smith recalled life with (see the replacement on xena & Hercules page 6), Stitch taste-tests the logo. -

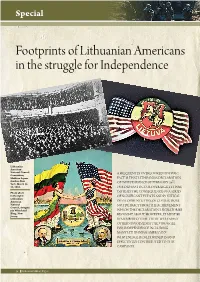

Lithuanian Independence Movement That Struggle Did Not Succeed, It Energized the Only Gradually Evolved in the Homeland

Special Footprints of Lithuanian Americans in the struggle for Independence Lithuanian American National Council A FREQUENTLY OVERLOOKED HISTORIC Convention, Madison Square FACT IS THAT LITHUANIA’S DECLARATION Garden, New TH York, March 13- OF INDEPENDENCE OF FEBRUARY 16 , 14, 1918. 1918, DID NOT OCCUR OVERNIGHT. IT WAS, Photo above INSTEAD, THE CONSEQUENCE OF A SERIES in the right: OF SIGNIFICANT EVENTS AND POLITICAL Lithuanian American DEVELOPMENTS. THIS, OF COURSE, DOES National NOT DETRACT FROM THE ACHIEVEMENT Council, delegate pin Whitehead WHICH THE DECLARATION’S SIGNATORIES Hoag, New BROUGHT ABOUT. HOWEVER, IT MUST BE Jersey. REMEMBERED THAT THERE WERE MANY OTHERS INVOLVED IN THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE INCLUDING MANY LITHUANIAN AMERICANS WHO ENERGETICALLY JOINED IN AND EFFECTIVELY CONTRIBUTED TO THIS CAMPAIGN. 16 Lithuanian Military Digest Special THE NATIONAL AWAKENING Independence — complete Lithuanian politi- t is generally agreed that the Lithuanian cal sovereignty a year before it was declared in National Awakening of the late 19th centu- Lithuania! ry and the resultant Lithuanian Indepen- Idence movement stemmed from the Polish- A LITHUANIAN MONARCHY? Lithuanian Insurrection of 1863–1864. While The Lithuanian independence movement that struggle did not succeed, it energized the only gradually evolved in the homeland. Initial- nation to continue its efforts to free itself from ly, the leaders of the movement merely sought Czarist rule. The consequent brutal suppres- some modicum of political autonomy, some sion of this insurrection led to an even greater accommodation within the framework of Czar- resolve to resist tyranny. The Russian regime ist Russian Empire. In 1905 the Russians were outlawed the publishing of books in the Lithu- routed in the ill-fated Russo-Japanese War. -

Note – Spoilers Ahead!!!!

Talking points for after the movie NOTE – SPOILERS AHEAD!!!! • The key chain in the gift bags is a special device that allows you to separate your car key from your house keys, so you can give it to the valet with peace of mind! • There are 5 different tips in the Bad Samaritan Safety Tip Series pencils included in the gift bags. The TIP # corresponds to the page in the script where the tip was gleaned. • The character who is the head of the FBI is played by the screenwriter Brandon Boyce, who also wrote Apt Pupil. • Kerry Condon, the victim in Bad Samaritan, is also in the biggest movie in America this weekend. She's the voice of Friday in Iron Man's suit. • According to Director Dean Devlin (Stargate, Independence Day, "Leverage", "The Librarians") the line "THAT'S HOW YOU &!@$&^# SAVE SOMEBODY" is the whole reason he made the movie. He loved the fact that it was the "helpless" woman victim that saved the hero, rather than the other way around. • In the original script, the handle doesn't break on the axe, and Robert Sheehan ends up killing Cale. After working with David Tennant, Dean wanted to keep his character alive. Which ending do you prefer? • Robert Sheehan (the protagonist in the movie), is a proud member of Legion M. He's even submitted his photo for the photomosaic. Have you?? (FYI-if you haven't, just go to www.legionm.com, click on "member benefits" and then "log into member portal". The shared password is topsecret. -

STARGATE by Dean Devlin & Roland Emmerich Devlin/Emmerich Draft 7

STARGATE by Dean Devlin & Roland Emmerich Devlin/Emmerich Draft 7/6/93 FADE IN: PRIMITIVE SKETCHES E.C.U. Etched on stone, a JACKAL. Another of a GAZELLE, a spear piercing its skin. Primitive, yet dramatic tribal etchings. The SOUND of ancient CHANTING is HEARD. Widen to REVEAL... 1 EXT. DESERT LANDSCAPE, NORTH AFRICA - SUNSET 1 A young BOY chisels his artwork into the stone ROCKFACE at the edge of this valley. An old MEDICINE MAN, his face painted with bizarre white stripes, CHANTS nearby. The boy abruptly stops his work at the SOUND of distant CRIES. Quickly he climbs the stone. Standing at the top he SEES... HUNTERS 2 RETURNING FROM A KILL. THEY MARCH TOWARDS A SMALL CAMPSITE. 2 The tribes people rushing to greet them. Super up: North Africa 8000 B.C. 3 OMITTED 3 4 A BLAZING FIRE - LATER THAT NIGHT 4 Silhouetted tribesmen dancing in bizarre animal MASKS. Feet STOMPING. The young Boy stares at the fire, SPARKS rising into the air. We PAN UP following the sparks into the sky. A full moon. A SHADOW is suddenly cast across the moon, blotting it out. 5 INT. TENT - LATER THAT NIGHT 5 The young Boy sleeps. Above him hangs an odd carving that slowly begins to RATTLE. The tent's fabric begins to FLAP. The Boy's eyes pop open. He HEARS the sounds of a quickly brewing storm. Footsteps. People hurrying, calling out to each other. Suddenly the tent's entrance flap SAILS OPEN. BRIGHT LIGHT pours in through the entrance. 6 EXT. CAMPSITE - NIGHT 6 The Boy exits his tent, staring at the light, intrigued. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism. -

DVD Profiler

101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure Animation Family Comedy2003 74 minG Coll.# 1 C Barry Bostwick, Jason Alexander, The endearing tale of Disney's animated classic '101 Dalmatians' continues in the delightful, all-new movie, '101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London A Martin Short, Bobby Lockwood, Adventure'. It's a fun-filled adventure fresh with irresistible original music and loveable new characters, voiced by Jason Alexander, Martin Short and S Susan Blakeslee, Samuel West, Barry Bostwick. Maurice LaMarche, Jeff Bennett, T D.Jim Kammerud P. Carolyn Bates C. W. Garrett K. SchiffM. Geoff Foster 102 Dalmatians Family 2000 100 min G Coll.# 2 C Eric Idle, Glenn Close, Gerard Get ready for outrageous fun in Disney's '102 Dalmatians'. It's a brand-new, hilarious adventure, starring the audacious Oddball, the spotless A Depardieu, Ioan Gruffudd, Alice Dalmatian puppy on a search for her rightful spots, and Waddlesworth, the wisecracking, delusional macaw who thinks he's a Rottweiler. Barking S Evans, Tim McInnerny, Ben mad, this unlikely duo leads a posse of puppies on a mission to outfox the wildly wicked, ever-scheming Cruella De Vil. Filled with chases, close Crompton, Carol MacReady, Ian calls, hilarious antics and thrilling escapes all the way from London through the streets of Paris - and a Parisian bakery - this adventure-packed tale T D.Kevin Lima P. Edward S. Feldman C. Adrian BiddleW. Dodie SmithM. David Newman 16 Blocks: Widescreen Edition Action Suspense/Thriller Drama 2005 102 min PG-13 Coll.# 390 C Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David From 'Lethal Weapon' director Richard Donner comes "a hard-to-beat thriller" (Gene Shalit, 'Today'/NBC-TV).