Drafting Machines and Parts Threof from Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surveying and Drawing Instruments

SURVEYING AND DRAWING INSTRUMENTS MAY \?\ 10 1917 , -;>. 1, :rks, \ C. F. CASELLA & Co., Ltd II to 15, Rochester Row, London, S.W. Telegrams: "ESCUTCHEON. LONDON." Telephone : Westminster 5599. 1911. List No. 330. RECENT AWARDS Franco-British Exhibition, London, 1908 GRAND PRIZE AND DIPLOMA OF HONOUR. Japan-British Exhibition, London, 1910 DIPLOMA. Engineering Exhibition, Allahabad, 1910 GOLD MEDAL. SURVEYING AND DRAWING INSTRUMENTS - . V &*>%$> ^ .f C. F. CASELLA & Co., Ltd MAKERS OF SURVEYING, METEOROLOGICAL & OTHER SCIENTIFIC INSTRUMENTS TO The Admiralty, Ordnance, Office of Works and other Home Departments, and to the Indian, Canadian and all Foreign Governments. II to 15, Rochester Row, Victoria Street, London, S.W. 1911 Established 1810. LIST No. 330. This List cancels previous issues and is subject to alteration with out notice. The prices are for delivery in London, packing extra. New customers are requested to send remittance with order or to furnish the usual references. C. F. CAS ELL A & CO., LTD. Y-THEODOLITES (1) 3-inch Y-Theodolite, divided on silver, with verniers to i minute with rack achromatic reading ; adjustment, telescope, erect and inverting eye-pieces, tangent screw and clamp adjustments, compass, cross levels, three screws and locking plate or parallel plates, etc., etc., in mahogany case, with tripod stand, complete 19 10 Weight of instrument, case and stand, about 14 Ibs. (6-4 kilos). (2) 4-inch Do., with all improvements, as above, to i minute... 22 (3) 5-inch Do., ... 24 (4) 6-inch Do., 20 seconds 27 (6 inch, to 10 seconds, 403. extra.) Larger sizes and special patterns made to order. -

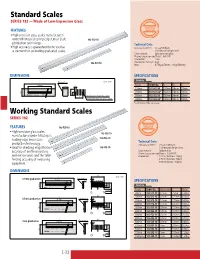

Standard Scales SERIES 182 — Made of Low-Expansion Glass

Standard Scales SERIES 182 — Made of Low-Expansion Glass FEATURES • High-precision glass scales manufactured under Mitutoyo’s leading-edge Linear Scale 182-502-50 production technology. Technical Data • High accuracy is guaranteed to be used as Accuracy (at 20°C): (0.5+L/1000)µm, a standard for calibrating graduated scales. L = Measured length (mm) Glass material: Low expansion glass Thermal expansion coefficient: 8x10-8/K Graduation: 1mm 182-501-50 Graduation thickness: 4µm Mass: 0.75kg (250mm), 1.8kg (500mm) DIMENSIONS SPECIFICATIONS Unit: mm Metric À>`Õ>Ì ,>}i / £ Range Order No. L W T 250mm 182-501-50 280mm 20mm 10mm { 7 250mm 182-501-60* 280mm 20mm 10mm Ó À>`Õ>ÌÊÌ ViÃÃ\Ê{ 500mm 182-502-50 530mm 30mm 20mm x }iÌÊ>ÀÊÌ ViÃÃ\ÊÓä 500mm 182-502-60* 530mm 30mm 20mm *with English JCSS certificate. Working Standard Scales SERIES 182 FEATURES 182-525-10 • High-precision glass scales 182-523-10 manufactured under Mitutoyo’s leading-edge linear scale 182-522-10 Technical Data production technology. Accuracy (at 20°C): (1.5+2L/1000)µm, • Ideal for checking magnification 182-513-10 L = Measured length (mm) accuracy of profile projectors Glass material: Sodium glass Thermal expansion coefficient: 8.5x10-6/K and microscopes, and the table Graduation: 0.1mm (thickness: 20µm) feeding accuracy of measuring 0.5mm (thickness: 50µm) equipment. 1mm (thickness: 100µm) DIMENSIONS £ä Unit: mm À>`Õ>Ì £ ä°£Ê}À>`Õ>Ì ,i}i Ó°Ç ä°£Ê}À>`Õ>Ì SPECIFICATIONS Ó°x Metric ΰx ÓÓ x Range Order No. -

MICHIGAN STATE COLLEGE Paul W

A STUDY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS AND INVENTIONS IN ENGINEERING INSTRUMENTS Thai: for III. Dean. of I. S. MICHIGAN STATE COLLEGE Paul W. Hoynigor I948 This]: _ C./ SUPP! '3' Nagy NIH: LJWIHL WA KOF BOOK A STUDY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS AND INVENTIONS IN ENGINEERING’INSIRUMENTS A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of MICHIGAN‘STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND.APPLIED SCIENCE by Paul W. Heyniger Candidate for the Degree of Batchelor of Science June 1948 \. HE-UI: PREFACE This Thesis is submitted to the faculty of Michigan State College as one of the requirements for a B. S. De- gree in Civil Engineering.' At this time,I Iish to express my appreciation to c. M. Cade, Professor of Civil Engineering at Michigan State Collegeafor his assistance throughout the course and to the manufacturers,vhose products are represented, for their help by freely giving of the data used in this paper. In preparing the laterial used in this thesis, it was the authors at: to point out new develop-ants on existing instruments and recent inventions or engineer- ing equipment used principally by the Civil Engineer. 20 6052 TAEEE OF CONTENTS Chapter One Page Introduction B. Drafting Equipment ----------------------- 13 Chapter Two Telescopic Inprovenents A. Glass Reticles .......................... -32 B. Coated Lenses .......................... --J.B Chapter three The Tilting Level- ............................ -33 Chapter rear The First One-Second.Anerican Optical 28 “00d011 ‘6- -------------------------- e- --------- Chapter rive Chapter Six The Latest Type Altineter ----- - ................ 5.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS , Chapter Seven Page The Most Recent Drafting Machine ........... -39.--- Chapter Eight Chapter Nine SmOnnB By Radar ....... - ------------------ In”.-- Chapter Ten Conclusion ------------ - ----- -. -

Schut for Precision

Schut for Precision Protractors / Clinometers / Spirit levels Accuracy of clinometers/spirit levels according DIN 877 Graduation Flatness (µm) µm/m " (L = length in mm) ≤ 50 ≤ 10 4 + L / 250 > 50 - 200 > 10 - 40 8 + L / 125 L > 200 > 40 16 + / 60 C08.001.EN-dealer.20110825 © 2011, Schut Geometrische Meettechniek bv 181 Measuring instruments and systems 2011/2012-D Schut.com Schut for Precision PROTRACTORS Universal digital bevel protractor This digital bevel protractor displays both decimal degrees and degrees-minutes-seconds at the same time. Measuring range: ± 360 mm. Reversible measuring direction. Resolution: 0.008° and 30". Fine adjustment. Accuracy: ± 0.08° or ± 5'. Delivery in a case with three blades (150, 200 Mode: 0 - 90°, 0 - 180° or 0 - 360°. and 300 mm), a square and an acute angle On/off switch. attachment. Reset/preset. Power supply: 1 battery type CR2032. Item No. Description Price 907.885 Bevel protractor Option: 495.157 Spare battery Single blades Item No. Blade length/mm Price 909.380 150 909.381 200 909.382 300 909.383 500 909.384 600 909.385 800 C08.302.EN-dealer.20110825 © 2011, Schut Geometrische Meettechniek bv 182 Measuring instruments and systems 2011/2012-D Schut.com Schut for Precision PROTRACTORS Universal digital bevel protractor This stainless steel, digital bevel protractor is Item No. Description Price available with blades from 150 to 1000 mm. The blades and all the measuring faces are hardened. 855.820 Bevel protractor Measuring range: ± 360°. Options: Resolution: 1', or decimal 0.01°. 495.157 Spare battery Accuracy: ± 2'. 905.409 Data cable 2 m Repeatability: 1'. -

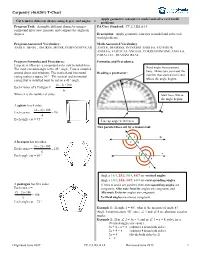

Carpentry T-Chart

Carpentry (46.0201) T-Chart Apply geometric concepts to model and solve real world Cut trim for different shapes using degree and angles = problems Program Task: Assemble different shapes by using a PA Core Standard: CC.2.3.HS.A.14 compound miter saw; measure and compare the angles in degrees. Description: Apply geometric concepts to model and solve real world problems. Program Associated Vocabulary: Math Associated Vocabulary ANGLE, BEVEL, DEGREE, MITER, PERPENDICULAR ANGLE, DEGREES, INTERIOR ANGLES, EXTERIOR ANGLES, VERTICAL ANGLES, CORRESPONDING ANGLES, PARALLEL, TRANSVERSAL Program Formulas and Procedures: Formulas and Procedures: Carpenters often use a compound miter saw to install trim. Read angle measurement The most common angle is the 45 ° angle. Trim is installed here. Make sure you read the around doors and windows. The vertical and horizontal Reading a protractor: number that started from zero casing makes a square 90 °. The vertical and horizontal casing that is installed must be cut on a 45 ° angle. where the angle begins. (n - 2)×180 Each Corner of a Polygon = n Where n is the number of sides. Start here, where the angle begins. A square has 4 sides. (4 2) 180 Each corner = 90 4 Each angle cut = 45 ° Line up angle vertex here. Two parallel lines cut by a transversal: 1 2 m A hexagon has six sides. 3 4 (6 2) 180 Each corner = 120 6 5 n Each angle cut = 60 ° 6 7 8 l Angles 1&4, 2&3, 5&8, 6&7 are vertical angles. Angles 1&5, 2&6, 3&7, 4&8 are corresponding angles. -

PRECISION ENGINEERING TOOLS WE HAVE WHAT IT TAKES to EXCEED & EXCEL the Plant

PRECISION ENGINEERING TOOLS WE HAVE WHAT IT TAKES TO EXCEED & EXCEL The plant. The people. The passion 500,000 sq ft manufacturing | integrated research & development | advanced cnc machining | quality assurance Groz has always exceeded the expectations of tool manufacturers and users the world over. Groz carefully makes each tool under stringent quality control processes that are achieved in a hi-tech manufacturing environment in a 500,000 square foot plant. If you demand quality, trust Groz. ADDITIONS 07 08 Straight Straight & Edge Knife Edges Squares Dear Valued Customer, It is my pleasure to present to you the new catalogue that covers our 13 17 range of Precision Engineering Multi-Use Magnetic Tools. Rule and Compass Gauge We have covered fair ground over the last few years and with our state-of-the art production facility, we can now do much more 22 31 than before. You will see many Electronic Adjustable technologically superior products Edge Finders Vee Block Set as well as modifications to some of the earlier designs, in the following pages. Further, I assure you of the same top performance to which you are accustomed to from Groz. 31 35 Ball Bearing Pot We appreciate your business and Vee Block & Magnets value your loyalty & trust. Clamp Sets Warm Regards, 37 38 Sine Bars Sine Plates ANIL BAMMI Managing Director 46 49 Tweezersezers Tap Wrenchesnches - Prefessionalnal 68 7777 Rotaryry RRapidap Headd AActionct Millingng DDrillri Pressressess VicesVices Machinehine VicesVi CA02 PRECISION ENGINEERING TOOLS 1 Measuring and Marking -

Simple Picture Framing

You can make it with Simple Pictu re Framing Professional picture framing is expensive. The Triton Workcentre enables you to cut the perfect mitres needed for picture framing, and use of the Router and Jigsaw Table makes it possible to shape your own simple mouldings. This project sheet differs from the others in that no dimensions are provided. Instead, we have provided you with a range of procedural options to guide you in making the picture frame that best meets your needs. 3tD &"u Tool 1. ESSENTIAL 1. Making your picture f rame f rom purchased moulding: Triton Workcentre and your power saw, f itted with a 40 or 60 tooth blade (essential for clean mitre cuts), mitre square or combination square, hammer, nail punch, sandpaper. 2. Shaping your own mouldings: Triton Accessory Router and Jigsaw Table, your router, and a selection of decorative router cutters. 3. A jig for working on end grain is needed if you intend to strengthen the mitres by use of a spline (See the Jig Guide for details of the jig). A small handsaw will also be necessary to trim the splines. 2. USEFUL: Mitre corner clamps to aid assembly, an extension fence mounted onto Face A of the double-sided protractor, and a mitred stop block, to ensure accurate cutting to length. @ Copyright Triton Manufacturing and Design Co. Pty. Ltd. /ssue No. 2, July 1989 Construction Details Material Shoppinq List 1. WOOD Any seasoned, straight-grained timber is suitable. To determine the total length of your frame material, the standard equation is: Twice the length plus twice the width of the picture, plus eight times the width of the moulding. -

Comments on Double-Theodolite Evaluations

322 BULLETIN AMERICAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY Comments on Double-Theodolite Evaluations ROBERT O. WEEDFALL AND WALTER M. JAGODZINSKI U. S. Weather Bureau (Original manuscript received 7 May 1960; revised manuscript received 26 August 1960) 1. Introduction After reading an article [1], in the May 1959 issue of the Bulletin of the AMS wherein Mssrs. Hansen and Taft describe another method of computing double-theodolite runs, it was realized that a method developed at the AEC installation at Yucca Flat, Nevada is even more efficient than any previous method and could be of great value in speed and saving of man-hours to those wind- research installations that use the double-theodo- lite method. Further, it does not need special plotting boards but utilizes the standard Weather Bureau equipment with a few ingenious adaptations. FIG. 1. Winds-aloft plotting board, showing position of three distance scales. (360-deg intervals not indicated.) 2. Materials needed (1) Winds-aloft plotting board (fig. 1). A 3-ft-square board with distance scales running from the center to the bottom, with a movable circular piece of plastic attached to the center of the board, whose outer edge is marked off in 360-deg intervals. (2) Circular protractor (fig. 2). A 10-inch- square piece of clear plastic divided into 360-deg intervals. (3) Appropriately marked scale in the shape of an "L" (fig. 3). (4) Scotch tape, rubber band and short piece of string. (5) Winds-aloft graphing board (fig. 4). A rectangular board 2 X 2% ft marked with height FIG. 2. Clear plastic protractor, 10 inches square. -

Current Practices Observed in Design and Drafting Occupations

OE6000 (REV 9-66) DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE ERIC ACCESSION NO. OFFICE OF EDUCATION (Top) ED 013 345 ERIC REPORT RESUME CLEARINGHOUSE ACCESSION NUMBER RESUME DATE P.A. T.A. IS DOCUMENT COPYRIGHTED? YES 0 001001VT 001 369 16 -01 -68 ERICREPRODUCTION RELEASE? YES 0 TITLE 1001 00Current Practices Observed in Design and Drafting Occupations. 101 102 103 PERSONAL AUTHOR(S) 200 200 Squires, Carl E. INSTITUTION (FOURCE) SOURCE CODE 300300 Maricopa County Junior Coll District Arizona 310310 REPORT/SERIES NO. OTHER SOURCE SOURCE CODE 320 320Arizona Dept. of Vocat. Educ., Technical Educ. Service 330 OTHER REPORT NO. OTHER SOURCE SOURCE CODE 340 350 OTHER REPORT NO. 400400PUB'L. DATE -66 CONTRACT /GRANT NUMBER PAGINATION, ETC. 500 500EDRS PRICEMF-$0.75HC-$5.24 / 129p. 501 RETRIEVAL TERMS 600600*DRAFTING, *DESIGN, CURRICULUM IMPROVEMENT., PROGRAM IMPROVEMENT, 601601TECHNICAL EDUCATION, OBSERVATION, TRADE AND INDUSTRIAL EDUCATION, 602602*INDUSTRY, EMPLOYMENT PRACTICES, OCCUPATIONAL SURVEYS, *PERSONNEL 603603POLICY, EDUCATIONAL NEEDS, *PHYSICAL FACILITIES, ORGANIZATION, 604 605 606 IDENTIFIERS 607607Maricopa County, Arizona ABSTRACT 800 800Data which had significance for design and drafting curriculums 801 801were collected by direct observation of 21 design and drafting 802802factors within 16 selected industrial companies employing 869 803803designers and draftsmen. Observations covered (1) the number of 8048014design and drafting employees, (2) the system of draftingroom 805805organization,. (3) Job classifications, (4) hiring, -

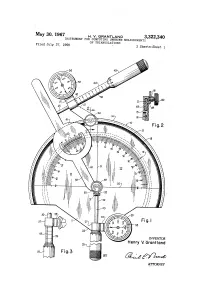

INVENTOR Henry V

May 30, 1967 H. W. GRANTAND 3,322,340 INSTRUMENT FOR COMPUTING UNKNOWN MEASUREMENTS Filed July 27, 1966 OF TRIANGULATIONS 3 Sheets-Sheet l 2 2 Z INVENTOR Henry V. Grant land ATTORNEY May 30, 1967 H. v. GRANTLAND 3,322,340 INSTRUMENT FOR cóMPUN UNKNOWN MEASUREMENTS OF TRIANGULATIONS Filed July 27, 1966 3 Sheets-Sheet a READS 30 FROM Vert CA READS 250 Fig. IO INVENTOR Henry V. Grontlond C = C, x C ose can C C - 250 x 2. OOO ... a = 5oo' au BY (2-4-6%2-2 Fig. ATTORNEY May 30, 1967 H. V. GRANTLAND 3,322,340 . INSTRUMENT FOR COMPUT ING UNKNOWN MEASUREMENTS OF TRIANGULATIONS Filed July 27, 1966 5. Sheets-Sheet : 3 READS 6O FROM VERTCA b = c x Cot angent C b = 250 x 1.732O b = 433' As 58-24S& 66 Fig. 16 5759-22 2S 2222 INVENTOR Henry V. Grant and Fig.19 BY (2-4%. ATTORNEY 3,322,340 United States Patent Office Patented May 30, 1967 1. 2 3,322,340 line 2-2 of FIGURE 1, illustrating the movable asso INSTRUMENT FOR COMPUTING UNKNOWN ciation between the upper micrometer and the protractor MEASUREMENTS OF TRANGULATIONS plate. Henry V. Grantland, Rte. 3, Box 105, FIGURE 3 is a fragmentary elevational illustration of Arlington, Tex. 76010 the lower micrometer barrel and the vernier dial mount Filed July 27, 1966, Ser. No. 568,250 ing attached thereto. 4 Claims. (C. 235-61) FIGURE 4 is a side elevational view of the invention. This invention relates to calculating devices, and it has FIGURE 5 is a fragmentary sectional view showing the particular reference to an instrument for computing un pivotal and slidable connection between the lower mi known measurements of either side of a triangle where O crometer and the angle scale, and between these elements the measurements and angulation of an acute angle and and the protractor plate. -

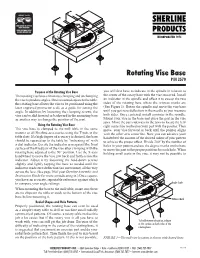

Rotating Vise Base P/N 3570

WEAR YOUR SAFETY GLASSES FORESIGHT IS BETTER THAN NO SIGHT READ INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE OPERATING Rotating Vise Base P/N 3570 Purpose of the Rotating Vise Base you will first have to indicate in the spindle in relation to The rotating vise base eliminates clamping and unclamping the center of the rotary base with the vise removed. Install the vise to produce angles. Once mounted square to the table, an indicator in the spindle and offset it to sweep the two the rotating base allows the vise to be positioned using the sides of the rotating base where the witness marks are laser engraved protractor scale as a guide for setting the (See Figure 1). Rotate the spindle and move the vise base angle. In addition, by loosening the clamping screws, the until you get zero deflection in the needle as you measure vise can be slid forward or backward in the mounting base both sides. Once centered, install a pointer in the spindle. as another way to change the position of the part. Mount your vise in the base and place the part in the vise jaws. Move the part sideways in the jaws to locate the left/ Using the Rotating Vise Base right centerline marked on your part with the pointer. Then The vise base is clamped to the mill table in the same move your vise forward or back until the pointer aligns manner as all Sherline accessories using the T-nuts in the with the other axis centerline. Now you can advance your table slots. If a high degree of accuracy is desired, the base handwheel the amount of the desired radius of your pattern should be squared up to the table by “indicating in” with to achieve the proper offset. -

World Bank Document

PROJECT : Vocational Training Improvement Project (VTIP) for Upgradation of Govt. Industrial Training Institute, Tura, Meghalaya, during Financial Year 2011-12 PACKAGE -1 HAND TOOLS TRADE SL.NO PARTICULARS SPECIFICATION QNTY UNIT RATE AMOUNT I II III IV V VI VII VIII DRAUGHTSMAN( 1 Box drawing instrument containing one 15 cm compass Box drawing instrument containing one 15 cm 16 Nos 595.00 9520.00 CIVIL) with pin point, pin point & lengthening bar, one pair compass with pin point, pin point & lengthening Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized spring bows, rotating compass with interchangeable ink bar, one pair spring bows, rotating compass with and pencil points, drawing pens with plain ponit & cross interchangeable ink and pencil points, drawing pens point, screw driver and box of leads. with plain ponit & cross point, screw driver and box of leads. 2 Protractor celluloid 15 cm semi-circular Protractor celluloid 15 cm semi-circular 16 Nos 65.00 1040.00 3 Scale card board-metric set of eight A to H in a box 1:1, Scale card board-metric set of eight A to H in a box 16 Sets 180.00 2880.00 1:2, 1:2:5, 1:5, 1:10, 1:20, 1:50, 1:100, 1:200, 1:500, 1:1000, 1:1, 1:2, 1:2:5, 1:5, 1:10, 1:20, 1:50, 1:100, 1:200, 1:1250, 1:6000, 1:38 1/3, 1:66 2/3 1:500, 1:1000, 1:1250, 1:6000, 1:38 1/3, 1:66 2/3 4 Scale - Metric and section wooden 30 cm long marked Scale - Metric and section wooden 30 cm long 16 Sets 180.00 2880.00 with eight scales - 1:1, 1:2, 1:2:5, 1:10, 1:20, 1:50, 1:100, marked with eight scales - 1:1, 1:2, 1:2:5, 1:10,