The Middle Finger and the Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Article

467 O'NEIL 2/28/2013 3:54 PM HATE SPEECH, FIGHTING WORDS, AND BEYOND—WHY AMERICAN LAW IS UNIQUE Robert M. O‘Neil* During the waning days of the turbulent presidential campaign of 2012, the issue of free speech was bound to emerge. President Barack Obama chose this moment to declare to the United Nations General Assembly his abiding commitment to the uniquely American value of unfettered expression.1 In a diverse society, he reaffirmed, ―efforts to restrict speech can become a tool to silence critics, or oppress minorities.‖2 The catalyst for this declaration was the appearance of ―a crude and disgusting video‖3 caricaturing the Prophet Muhammad which had triggered violent protests in more than twenty nations, mainly in the Middle East.4 President Obama made clear both his disdain for the video and his unswerving faith in the singularly American insistence on free expression.5 Curiously (or some would say paradoxically) the Obama Administration only weeks earlier had actively supported passage of a resolution in the United Nations Human Rights Council to create an international standard restricting some anti-religious speech; the Egyptian ambassador to the United Nations had lauded this measure by recognizing that ―‗freedom of expression has been sometimes misused‘ to insult religion.‖6 Secretary of State Hilary Clinton had added her view that speech or protest resulting in the destruction of religious sites was not, she noted, ―fair game.‖7 In a recent and expansive analysis of these contrasting events, * University of Virginia and Association of Governing Boards, Albany Law Review Symposium, September, 2012. -

PE2260 Five-Finger Exercise

The Five-Finger Exercise The 5-finger exercise is helpful for relaxation and calming your system. It does not take long, but can help you feel much more peaceful and relaxed and help you feel better about yourself. Try it any time you feel tension. What are the steps to the 5-finger exercise? On one hand, touch your thumb to your index finger. Think back to a time you felt tired after exercise or some other fun physical activity. Touch your thumb to your middle finger. Go back to a time when you had a loving experience. You might recall a loving day with your family or a good friend, a warm hug from a parent or a time you had a really good conversation with someone. Touch your thumb to your ring finger. Remember the nicest compliment anyone ever gave you. Try to accept it now fully. When you do this, you are showing respect for the person who said it. You are really paying them a compliment in return. Touch your thumb to your little finger. Go back in your mind to the most beautiful and relaxing place you have ever been. Spend some time thinking of being there. To Learn More Free Interpreter Services • Adolescent Medicine • In the hospital, ask your nurse. 206-987-2028 • From outside the hospital, call the toll-free Family Interpreting Line, • Ask your healthcare provider 1-866-583-1527. Tell the interpreter • seattlechildrens.org the name or extension you need. Seattle Children’s offers interpreter services for Deaf, hard of hearing or non-English speaking patients, family members and legal representatives free of charge. -

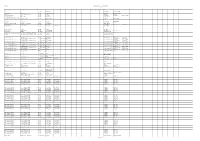

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

This List of Gestures Represents Broad Categories of Emotion: Openness

This list of gestures represents broad categories of emotion: openness, defensiveness, expectancy, suspicion, readiness, cooperation, frustration, confidence, nervousness, boredom, and acceptance. By visualizing the movement of these gestures, you can raise your awareness of the many emotions the body expresses without words. Openness Aggressiveness Smiling Hand on hips Open hands Sitting on edge of chair Unbuttoning coats Moving in closer Defensiveness Cooperation Arms crossed on chest Sitting on edge of chair Locked ankles & clenched fists Hand on the face gestures Chair back as a shield Unbuttoned coat Crossing legs Head titled Expectancy Frustration Hand rubbing Short breaths Crossed fingers “Tsk!” Tightly clenched hands Evaluation Wringing hands Hand to cheek gestures Fist like gestures Head tilted Pointing index finger Stroking chins Palm to back of neck Gestures with glasses Kicking at ground or an imaginary object Pacing Confidence Suspicion & Secretiveness Steepling Sideways glance Hands joined at back Feet or body pointing towards the door Feet on desk Rubbing nose Elevating oneself Rubbing the eye “Cluck” sound Leaning back with hands supporting head Nervousness Clearing throat Boredom “Whew” sound Drumming on table Whistling Head in hand Fidget in chair Blank stare Tugging at ear Hands over mouth while speaking Acceptance Tugging at pants while sitting Hand to chest Jingling money in pocket Touching Moving in closer Dangerous Body Language Abroad by Matthew Link Posted Jul 26th 2010 01:00 PMUpdated Aug 10th 2010 01:17 PM at http://news.travel.aol.com/2010/07/26/dangerous-body-language-abroad/?ncid=AOLCOMMtravsharartl0001&sms_ss=digg You are in a foreign country, and don't speak the language. -

UK Clinical Guideline for Best Practice in the Use of Vaginal Pessaries for Pelvic Organ Prolapse

UK Clinical Guideline for best practice in the use of vaginal pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse March 2021 Developed by members of the UK Clinical Guideline Group for the use of pessaries in vaginal prolapse representing: the United Kingdom Continence Society (UKCS); the Pelvic Obstetric and Gynaecological Physiotherapy (POGP); the British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG); the Association for Continence Advice (ACA); the Scottish Pelvic Floor Network (SPFN); The Pelvic Floor Society (TPFS); the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG); the Royal College of Nursing (RCN); and pessary users. Funded by grants awarded by UKCS and the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP). This guideline was completed in December 2020, and following stakeholder review, has been given official endorsement and approval by: • British Association of Urological Nurses (BAUN) • International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) • Pelvic Obstetric and Gynaecological Physiotherapy (POGP) • Scottish Pelvic Floor Network (SPFN) • The Association of Continence Advice (ACA) • The British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG) • The Pelvic Floor Society (TPFS) • The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) • The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) • The United Kingdom Continence Society (UKCS) Review This guideline will be due for full review in 2024. All comments received on the POGP and UKCS websites or submitted here: [email protected] will be included in the review process. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................ -

Hand Gestures

L2/16-308 More hand gestures To: UTC From: Peter Edberg, Emoji Subcommittee Date: 2016-10-31 Proposed characters Tier 1: Two often-requested signs (ILY, Shaka, ILY), and three to complete the finger-counting sets for 1-3 (North American and European system). None of these are known to have offensive connotations. HAND SIGN SHAKA ● Shaka sign ● ASL sign for letter ‘Y’ ● Can signify “Aloha spirit”, surfing, “hang loose” ● On Emojipedia top requests list, but requests have dropped off ● 90°-rotated version of CALL ME HAND, but EmojiXpress has received requests for SHAKA specifically, noting that CALL ME HAND does not fulfill need HAND SIGN ILY ● ASL sign for “I love you” (combines signs for I, L, Y), has moved into mainstream use ● On Emojipedia top requests list HAND WITH THUMB AND INDEX FINGER EXTENDED ● Finger-counting 2, European style ● ASL sign for letter ‘L’ ● Sign for “loser” ● In Montenegro, sign for the Liberal party ● In Philippines, sign used by supporters of Corazon Aquino ● See Wikipedia entry HAND WITH THUMB AND FIRST TWO FINGERS EXTENDED ● Finger-counting 3, European style ● UAE: Win, victory, love = work ethic, success, love of nation (see separate proposal L2/16-071, which is the source of the information below about this gesture, and also the source of the images at left) ● Representation for Ctrl-Alt-Del on Windows systems ● Serbian “три прста” (tri prsta), symbol of Serbian identity ● Germanic “Schwurhand”, sign for swearing an oath ● Indication in sports of successful 3-point shot (basketball), 3 successive goals (soccer), etc. HAND WITH FIRST THREE FINGERS EXTENDED ● Finger-counting 3, North American style ● ASL sign for letter ‘W’ ● Scout sign (Boy/Girl Scouts) is similar, has fingers together Tier 2: Complete the finger-counting sets for 4-5, plus some less-requested hand signs. -

Warmsley Cornellgrad 0058F 1

ON THE DETECTION OF HATE SPEECH, HATE SPEAKERS AND POLARIZED GROUPS IN ONLINE SOCIAL MEDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Dana Warmsley December 2017 c 2017 Dana Warmsley ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ON THE DETECTION OF HATE SPEECH, HATE SPEAKERS AND POLARIZED GROUPS IN ONLINE SOCIAL MEDIA Dana Warmsley, Ph.D. Cornell University 2017 The objective of this dissertation is to explore the use of machine learning algorithms in understanding and detecting hate speech, hate speakers and po- larized groups in online social media. Beginning with a unique typology for detecting abusive language, we outline the distinctions and similarities of dif- ferent abusive language subtasks (offensive language, hate speech, cyberbully- ing and trolling) and how we might benefit from the progress made in each area. Specifically, we suggest that each subtask can be categorized based on whether or not the abusive language being studied 1) is directed at a specific individ- ual, or targets a generalized “Other” and 2) the extent to which the language is explicit versus implicit. We then use knowledge gained from this typology to tackle the “problem of offensive language” in hate speech detection. A key challenge for automated hate speech detection on social media is the separation of hate speech from other instances of offensive language. We present a Logistic Regression classifier, trained on human annotated Twitter data, that makes use of a uniquely derived lexicon of hate terms along with features that have proven successful in the detection of offensive language, hate speech and cyberbully- ing. -

Female Pelvic Relaxation

FEMALE PELVIC RELAXATION A Primer for Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse Written by: ANDREW SIEGEL, M.D. An educational service provided by: BERGEN UROLOGICAL ASSOCIATES N.J. CENTER FOR PROSTATE CANCER & UROLOGY Andrew Siegel, M.D. • Martin Goldstein, M.D. Vincent Lanteri, M.D. • Michael Esposito, M.D. • Mutahar Ahmed, M.D. Gregory Lovallo, M.D. • Thomas Christiano, M.D. 255 Spring Valley Avenue Maywood, N.J. 07607 www.bergenurological.com www.roboticurology.com Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................1 WHY A UROLOGIST? ..........................................................2 PELVIC ANATOMY ..............................................................4 PROLAPSE URETHRA ....................................................................7 BLADDER .....................................................................7 RECTUM ......................................................................8 PERINEUM ..................................................................9 SMALL INTESTINE .....................................................9 VAGINAL VAULT .......................................................10 UTERUS .....................................................................11 EVALUATION OF PROLAPSE ............................................11 SURGICAL REPAIR OF PELVIC PROLAPSE .....................15 STRESS INCONTINENCE .........................................16 CYSTOCELE ..............................................................18 RECTOCELE/PERINEAL LAXITY .............................19 -

Free Speech Or Hate Speech? a Conversation Regarding State V

Free Speech or Hate Speech? A Conversation Regarding State v. Liebenguth November 16, 2020 4:00 p.m. – 6:00 p.m. CT Bar Association Webinar CT Bar Institute, Inc. CT: 2.0 CLE Credits (1.0 General / 1.0 Ethics) NY:2.0 CLE Credits (1.0 AOP / 1.0 Ethics) No representation or warranty is made as to the accuracy of these materials. Readers should check primary sources where appropriate and use the traditional legal research techniques to make sure that the information has not been affected or changed by recent developments. Page 1 of 163 Table of Contents Lawyers’ Principles of Professionalism...................................................................................................................3 Agenda ....................................................................................................................................................................6 Faculty Biographies ................................................................................................................................................7 Hate Crime Laws ..................................................................................................................................................10 State v. Liebenguth ................................................................................................................................................26 State v. Liebenguth 181 Conn.App. 37 ..................................................................................................................49 State v. Baccala .....................................................................................................................................................67 -

DECEMBER 08 Doing Business Globally Requires More Than Compliance with Legal Mandates

ows When stepping into a foreign country, be sure to start on the right foot. DECEMBER 08 Doing business globally requires more than compliance with legal mandates. Knowledge of local customs is also critical, especially when making a first impression. A monthly best practices alert for multinationals confronting the As 2008 draws to a close (none too soon), and we all look forward to greeting the New challenges of the global workplace Year, we offer some tips on how to say hello in countries around the world. This Month’s With best wishes from the International Labor Group. Challenge When doing business abroad, Hugs and Business Gestures/ not knowing the local customs Country Handshake Eye Contact Other Kisses Cards Physical Space can lead to serious embarrassment. EUROPE UK A handshake Generally Customs Avoid Direct eye Pants actually Best Practice is the most no kissing similar to excessive hand contact is means appropriate or hugging. U.S. gestures and common and underwear, not Tip of the Month greeting. displays of acceptable, but trousers. emotion. don’t be too A little preparation can prevent intense. a lot of trouble. Get to know France A handshake In social Cards The U.S. sign Direct eye Always apologize the local customs before is the most settings, should be for ok means contact is if you do not embarking for an international appropriate friends do printed in zero in France. common and speak French business meeting. greeting and les bises English acceptable, and or if you need to farewell. (touching on one sometimes conduct business However, cheeks and side and intense. -

Civilian Killings and Disappearances During Civil War in El Salvador (1980–1992)

DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH A peer-reviewed, open-access journal of population sciences DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH VOLUME 41, ARTICLE 27, PAGES 781–814 PUBLISHED 1 OCTOBER 2019 http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol41/27/ DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2019.41.27 Research Article Civilian killings and disappearances during civil war in El Salvador (1980–1992) Amelia Hoover Green Patrick Ball c 2019 Amelia Hoover Green & Patrick Ball. This open-access work is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Germany (CC BY 3.0 DE), which permits use, reproduction, and distribution in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are given credit. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/de/legalcode Contents 1 Introduction 782 2 Background 783 3 Methods 785 3.1 Methodological overview 785 3.2 Assumptions of the model 786 3.3 Data sources 787 3.4 Matching and merging across datasets 790 3.5 Stratification 792 3.6 Estimation procedure 795 4 Results 799 4.1 Spatial variation 799 4.2 Temporal variation 802 4.3 Global estimates 803 4.3.1 Sums over strata 805 5 Discussion 807 6 Conclusions 808 References 810 Demographic Research: Volume 41, Article 27 Research Article Civilian killings and disappearances during civil war in El Salvador (1980–1992) Amelia Hoover Green1 Patrick Ball2 Abstract BACKGROUND Debate over the civilian toll of El Salvador’s civil war (1980–1992) raged throughout the conflict and its aftermath. Apologists for the Salvadoran regime claimed no more than 20,000 had died, while some activists placed the toll at 100,000 or more. -

How Informal Justice Systems Can Contribute

United Nations Development Programme Oslo Governance Centre The Democratic Governance Fellowship Programme Doing Justice: How informal justice systems can contribute Ewa Wojkowska, December 2006 United Nations Development Programme – Oslo Governance Centre Contents Contents Contents page 2 Acknowledgements page 3 List of Acronyms and Abbreviations page 4 Research Methods page 4 Executive Summary page 5 Chapter 1: Introduction page 7 Key Definitions: page 9 Chapter 2: Why are informal justice systems important? page 11 UNDP’s Support to the Justice Sector 2000-2005 page 11 Chapter 3: Characteristics of Informal Justice Systems page 16 Strengths page 16 Weaknesses page 20 Chapter 4: Linkages between informal and formal justice systems page 25 Chapter 5: Recommendations for how to engage with informal justice systems page 30 Examples of Indicators page 45 Key features of selected informal justice systems page 47 United Nations Development Programme – Oslo Governance Centre Acknowledgements Acknowledgements I am grateful for the opportunity provided by UNDP and the Oslo Governance Centre (OGC) to undertake this fellowship and thank all OGC colleagues for their kindness and support throughout my stay in Oslo. I would especially like to thank the following individuals for their contributions and support throughout the fellowship period: Toshihiro Nakamura, Nina Berg, Siphosami Malunga, Noha El-Mikawy, Noelle Rancourt, Noel Matthews from UNDP, and Christian Ranheim from the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights. Special thanks also go to all the individuals who took their time to provide information on their experiences of working with informal justice systems and UNDP Indonesia for releasing me for the fellowship period. Any errors or omissions that remain are my responsibility alone.