Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecovillaggi: Esperienze Comunitarie Tra Utopia E Realtà

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive - Università di Pisa UNIVERSITÀ DI PISA DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE POLITICHE E SOCIALI CORSO DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN STORIA E SOCIOLOGIA DELLA MODERNITÀ Ecovillaggi: esperienze comunitarie tra utopia e realtà CANDIDATA Rossana Guidi TUTOR Prof. Mario Aldo Toscano Ciclo 2007-2009 1 L’utopia del futuro costruisce il presente. (Prigogine) 2 Indice: Introduzione…………………………………………………… p. 5. Parte I: Industrializzazione, capitalismo, modernità………...p. 12. 1.1 Nascita della società capitalistica moderna………………...p. 13. Parte II: Le avventure intellettuali e pratiche della comunità. ……………………………………………………………………p. 26. 2.2.1 Dissoluzione e resistenze della comunità………………... p. 26. 2.2.2 Tracce di comunità……………………………………..... p. 36. 2.2.3 Dalla comunità alla società: il pensiero degli autori classici della sociologia…………………………………..p. 41. Parte III: Il pensiero utopico e le sue realizzazioni……………p. 57 3.1 Socialisti utopisti……………………………………………..p. 57. 3.2 Comunitarismo americano…………………………………...p. 69. 3.3 Movimento Hippy……………………………………………p. 82. 3.4 Sviluppo sostenibile e nascita degli ecovillaggi…………….p. 86. Parte IV: Fenomenologia e geopolitica dell’ecovillaggio……p. 100. 4.1 Definizione di ecovillaggio…………………………… p. 100. 4.2 Ecovillaggi a confronto………………………………... p. 110. 4.2.1 Il metodo decisionale…………………………………...p. 113. 4.3.2 Organizzazione economica……………………………..p. 124. 4.3.3 Accorgimenti ecologici………………………………..p. 130. 3 4.3.4 Orientamento religioso………………………………...p. 138. 4.4 Ecovillaggi: tra utopia e realtà………………………....p. 140. 4.5 Contenuto razionalistico degli ecovillaggi…………….p. 151. 4.6 Breve quadro concettuale sulla disuguaglianza sociale..p. 168. Parte V: Punto applicativo e descrizione di un caso specifico: la comune di Bagnaia……………………………………….……p. -

The Historical Journal VIA RASELLA, 1944

The Historical Journal http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS Additional services for The Historical Journal: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY JOHN FOOT The Historical Journal / Volume 43 / Issue 04 / December 2000, pp 1173 1181 DOI: null, Published online: 06 March 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0018246X00001400 How to cite this article: JOHN FOOT (2000). VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY. The Historical Journal, 43, pp 11731181 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS, IP address: 144.82.107.39 on 26 Sep 2012 The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – Printed in the United Kingdom # Cambridge University Press REVIEW ARTICLE VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY L’ordine eZ giaZ stato eseguito: Roma, le Fosse Ardeatine, la memoria. By Alessandro Portelli. Rome: Donzelli, . Pp. viij. ISBN ---.L... The battle of Valle Giulia: oral history and the art of dialogue. By A. Portelli. Wisconsin: Wisconsin: University Press, . Pp. xxj. ISBN ---.$.. [Inc.‘The massacre at Civitella Val di Chiana (Tuscany, June , ): Myth and politics, mourning and common sense’, in The Battle of Valle Giulia, by A. Portelli, pp. –.] Operazione Via Rasella: veritaZ e menzogna: i protagonisti raccontano. By Rosario Bentivegna (in collaboration with Cesare De Simone). Rome: Riuniti, . Pp. ISBN -- -.L... La memoria divisa. By Giovanni Contini. Milan: Rizzoli, . Pp. ISBN -- -.L... Anatomia di un massacro: controversia sopra una strage tedesca. By Paolo Pezzino. Bologna: Il Mulino, . Pp. ISBN ---.L... Processo Priebke: Le testimonianze, il memoriale. Edited by Cinzia Dal Maso. -

Tv Shows, Feature Films & Documentaries

TV SHOWS, FEATURE FILMS & DOCUMENTARIES TITLES AVAILABLE DUBBED AND SUBTITLED IN SPANISH. INDEX INDEX TITLES AVAILABLE DUBBED ...And It’s Snowing Outside! 6 Grand Torino (The) 27 Storm (The) 14 Angel Of Sarajevo (The) 6 Hidden Vatican (The) 7 Terra Sancta: Guardians Of Salvation’s Source 25 Assault (The) 10 Imperium: Nero 19 Third Secret Of Fatima (The) 27 Bartali, The Iron Man 16 Imperium: Pompeii 19 Third Truth (The) 28 Borsellino, The 57 Days 12 Imperium: Saint Augustine 20 Turin’s Butterfly 11 Boss In The Kitchen (A) 9 Imperium: Saint Peter 20 Wannabe Widowed 12 Bright Flight 13 Lady Of The Camellias 21 Caravaggio 16 Long Lasting Youth 21 Claire & Francis 17 Maria Goretti 28 Countess Of Castiglione (The) 25 Marriage (A) 8 Curfew - Don Pappagallo (The) 26 Mearshes Intrique (The) 22 Displaced Child (The) 11 My House Is Full Of Mirrors 15 Don Zeno 17 Oro Di Scampia (L’) 7 Fear Of Loving 1, 2 9 Over The Shop 13 Francesco 22 Pompeii, Stories From An Eruption 23 Frederick Barbarossa 15 Resurrection 23 Giovanni Falcone, The Judge 18 Saint Bakhita 24 Girls Of San Frediano (The) 26 Scent Of Love 14 Giuseppe Moscati, 18 Song’e Napule 10 Good Season (A) 8 Star Of Bethlehem 24 Credits not contractual Credits INDEX TITLES AVAILABLE SUBTITLED Anija 36 Lonely Hero (A) 42 Away From Me 33 Smile Of The Leader (The) 35 Balancing Act (The) 37 Song’e Napule 34 Black Souls 31 Triplet (The) 39 Caesar Must Die 36 Viva La Libertà 35 Cardboard Village (The) 40 Chair Of Happiness (The) 34 Darker Than Midnight 31 Dinner (The) 32 Easy 40 Entrepreneur (The) 41 -

Preparatory Document

Preparatory document Please notice that we recommend that you read the first ten pages of the first three documents, the last document is optional. • International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, Recognizing and Countering Holocaust Distortion: Recommendations for Policy and Decision Makers (Berlin: International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, 2021), read esp. pp. 14-24 • Deborah Lipstadt, "Holocaust Denial: An Antisemitic Fantasy," Modern Judaism 40:1 (2020): 71-86 • Keith Kahn Harris, "Denialism: What Drives People to Reject the Truth," The Guardian, 3 August 2018, as at https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/aug/03/denialism-what-drives- people-to-reject-the-truth (attached as pdf) • Optional reading: Giorgio Resta and Vincenzo Zeno-Zencovich, "Judicial 'Truth' and Historical 'Truth': The Case of the Ardeatine Caves Massacre," Law and History Review 31:4 (2013): 843- 886 Holocaust Denial: An Antisemitic Fantasy Deborah Lipstadt Modern Judaism, Volume 40, Number 1, February 2020, pp. 71-86 (Article) Published by Oxford University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/750387 [ Access provided at 15 Feb 2021 12:42 GMT from U S Holocaust Memorial Museum ] Deborah Lipstadt HOLOCAUST DENIAL: AN ANTISEMITIC FANTASY* *** When I first began working on the topic of Holocaust deniers, colleagues would frequently tell me I was wasting my time. “These people are dolts. They are the equivalent of flat-earth theorists,” they would insist. “Forget about them.” In truth, I thought the same thing. In fact, when I first heard of Holocaust deniers, I laughed and dismissed them as not worthy of serious analysis. Then I looked more closely and I changed my mind. -

Nome DE VREESE LUC PIETER Indirizzo 210/1, VIA DON ZENO

F ORMATO EUROPEO PER IL CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome DE VREESE LUC PIETER Indirizzo 210/1, VIA DON ZENO SALTINI, 41123 MODENA, ITALIA Telefono +39 3396447373 E-mail [email protected]; [email protected] Nazionalità Belga (con residenza anagrafica e fiscale in Italia) Data di nascita 23/02/1958 ESPERIENZA LAVORATIVA • Date (da – a) DA MARZO 2016 (ANCORA IN CORSO) • Nome e indirizzo del datore di Fondazione Luigi Boni Onlus, Viale Luigi Cadorna, 4 46029 Suzzara (MN lavoro • Tipo di azienda o settore Terzo Settore: Servizi (semi)residenziali e domiciliari socio-sanitari • Tipo di impiego Medico Libero professionista (fino al 30/09/2016) - Dirigente Medico (CCNL Dirigenti Sanità Pubblica Area IV a tempo indeterminato e a tempo parziale 30 ore settimanali) • Principali mansioni e responsabilità − Medico Referente RSA 2 (p.l. 80) e del Centro Diurno Integrato (20 posti) della Fondazione Luigi Boni Onlus (fino al 31/05/2018) − Direttore Sanitario della Fondazione Luigi Boni Onlus che ha le seguenti U.d.O.: RSA1 (85 p.l.); RSA2 (p.l. 80); CDI (20 posti); ADI; RSA aperta e Poliambulatorio (dal 1/06/2018) Referente COVID (da Aprile 2020) − − Visite psicogeriatriche ambulatoriali o domiciliari in libera professione • Date (da – a) DAL 1/03/2018 AL 31/12/2020 • Nome e indirizzo del datore di Cooperativa Sociale Villa Maria (Disabilità Intellettiva Adulta e Anziana), Via Castelbeseno, 8 lavoro 38060 Calliano (TN) • Tipo di azienda o settore Terzo Settore: Residenze Socio-Sanitarie • Tipo di impiego Direttore Sanitario con contratto libero professionale (fino al 06/01/2020) – Direttore Sanitario a tempo determinato “acausale” – categoria “Q” (Quadri) per una prestazione media complessiva di 8 ore settimanali • Principali mansioni e responsabilità Direttore Sanitario delle 2 residenze socio-sanitarie (Villa Maria a Calliano 42 p.l. -

Michele Ranchetti

Archivio Michele Ranchetti Biografia Marco Pacioni Elenco analitico dei documenti Rita Romanelli Archivio Michele Ranchetti Biografia Marco Pacioni Elenco analitico dei documenti Rita Romanelli SOMMARIO Biografia di Michele Ranchetti (M. Pacioni)1* pag. 7 Bibliografia (M. Pacioni) pag. 15 L’archivio di Michele Ranchetti (R. Romanelli) pag. 21 Elenco analitico dei documenti (R. Romanelli) pag. 23 Corrispondenza pag. 23 Poesie pag. 24 Appunti manoscritti pag. 25 Testi dattiloscritti e a stampa pag. 28 Dattiloscritti su storia e cristianesimo pag. 28 Dattiloscritti su autori e testi pag. 29 Dattiloscritti su Freud e psicanalisi pag. 30 Saggi e articoli di Michele Ranchetti pag. 31 Saggi su Michele Ranchetti e interviste pag. 31 Testi di e su Ranchetti degli ultimi anni pag. 33 Temi di studio pag. 35 Diodati pag. 35 Padri della chiesa pag. 36 Antico e nuovo testamento pag. 37 Storia della Chiesa - Papi, concilii pag. 37 Pascal pag. 38 Catechismi – Schelling – S. Paolo pag. 39 Lutero pag. 41 Modernismo pag. 43 Pensiero religioso – ebraismo pag. 43 Storia della chiesa – Università pag. 45 Legislazione ecclesiastica pag. 45 Filosofia, logica e teologia – autori A-Z pag. 45 Benjamin e Scholem pag. 50 Taubes e Schmidt pag. 51 Heidegger pag. 51 Bultmann e Barth pag. 52 Bonhoeffer pag. 52 Fonti di filosofia e logica pag. 52 Wittgenstein pag. 53 Freud e psicoanalisi pag. 56 Dattiloscritti su Freud pag. 57 Freud e Fliess pag. 58 Freud e Ranck pag. 58 Psicologia e psicoanalisi pag. 58 Copie di saggi editi su Freud pag. 59 1 * La biografia è la versione più estesa della voce Michele Ranchetti scritta da Marco Pacioni per il Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Treccani. -

Primo Levi and the Material World

Gerry Kearns1 If wood were an element: Primo Levi and the material world Abstract The precarious survival of a single shed from the Jewish slave labour quarters of the industrial complex that was Auschwitz- Monowitz offers an opportunity to reflect upon aspects of the materiality of the signs of the Holocaust. This shed is very likely ne that Primo Levi knew and its survival incites us to interrogate its materiality and significance by engaging with Levi’s own writings on these matters. I begin by explicating the ways the shed might function as an ‘encountered sign,’ before moving to consider its materiality both as a product of modernist genocide and as witness to the relations between precarity and vitality. Finally, I turn to the texts written upon the shed itself and turn to the performative function of Nazi language. Keywords Holocaust, icon, index, materiality, performativity, Primo Levi Fig. 1 - The interior of the shed, December 2012 (Photograph by kind permission of Carlos Reijnen) It is December 2012, we are near the town of Monowice in Poland. Alongside a small farmhouse, there is a hay-shed. The shed is in two parts with two doorways communicating and above these, “Eingang” and “Ausgang”. In the further part of the shed, there is more text, in Gothic font, in German. Along a crossbeam 1 National University of Ireland, Maynooth; [email protected]. I want to thank the directors of the Terrorscapes Project (Rob van der Laarse and Georgi Verbeeck) for the invitation to come on the field trip to Auschwitz. I want to thank Hans Citroen and Robert Jan van Pelt for their patient teaching about the history of the site. -

Don Zeno Saltini

DON ZENO SALTINI Fossoli, 30 agosto 1900 - Grosseto, 15 gennaio 1981 è stato il presbitero italiano, fondatore della comunità Nomadelfia. a cura di Lucio Bregoli Circolo Acli - Vittorio Loda - Villaggio Prealpino 1900 - LA FAMIGLIA DI DON ZENO 30 agosto 1900. A Fossoli di Carpi (MO), in una benestante famiglia patriarcale, da Cesare Saltini e Filomena Righi nasce Zeno. È il nono di dodici figli. La famiglia di don Zeno Saltini nel 1916. Zeno è il primo seduto a sinistra Tra questi Marianna, conosciuta come Mamma Nina (1889-1957), farà nascere a Carpi la Casa della Divina Provvidenza che si occupa di ragazze in stato di abbandono. Marianna Saltini con in braccio una piccola abbandonata Il fratello don Vincenzo (1896-1961) darà vita all’Istituto degli Oblati, per formare sacerdoti in grado di divenire educatori nei seminari; Anita entrerà nel monastero delle Clarisse di Carpi con il nome di suor Scolastica. Don Vincenzo Saltini Monastero delle Clarisse di Carpi 1914 - IL RIFIUTO DELLA SCUOLA A 14 anni e mezzo Zeno rifiuta di andare a scuola, strappando il permesso al padre con l’intervento del parroco, don Sisto Campagnoli, che sempre lo comprenderà e lo aiuterà. Sostiene che a scuola inse- gnano cose che non incidono sulla vita. 1912. Zeno in mezzo alla sua classe in 5ª elementare (al centro) Il padre lo manda a lavorare nei poderi della famiglia, vive in mezzo ai braccianti e ne condivide le giuste aspirazioni. Ha così modo di entrare a contatto con la dura realtà dei braccianti da cui imparò le teorie socialiste. Zeno al lavoro nei campi Una delle numerose cooperative agricole dell’Emilia Romagna Mezzo di trasporto preferito dal giovane Zeno 1920 - LA DISCUSSIONE CON L’ANARCHICO A 17 anni è chiamato sotto le armi, durante la prima guerra mondiale, e presta servizio militare fino al marzo del 1919. -

Das Massaker Der Fosse Ardeatine Und Die Taterverfolgung. Deutsch-Italienische Störfalle Von Kappler Bis Priebke

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of 2012 Das Massaker der Fosse Ardeatine und die Taterverfolgung. Deutsch-italienische Störfalle von Kappler bis Priebke Gerald Steinacher University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Steinacher, Gerald, "Das Massaker der Fosse Ardeatine und die Taterverfolgung. Deutsch-italienische Störfalle von Kappler bis Priebke" (2012). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Michael Gehler . Maddalena Guiotto (Hrsg.) ITALIEN, ÖSTERREICH UND DIE BUNDES REPUBLIK DEUTSCHLAND IN EUROPA Ein Dreiecksverhältnis in seinen wechselseitigen Beziehungen und Wahrnehmungen von 1945/49 bis zur Gegenwart ITALY, AUSTRIA AND THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY IN EUROPE A Triangle of Mutual Relations and Perceptions from the Period 1945-49 to the Present Unter Mitarbeit von Imke Scharlemann BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN· KÖLN· WEIMAR Gedruckt mit der Unterstützung durch das Bundnministlrium fßrWissenschlltund Forselluna Bundesministerium fiir Wissenschaft und Forschung in Wien und AUTONOME PROVINCIA PROVINZ ·W.i • AUTONOMA BOZEN, ! 01 BOLZANO SÜDTIROL \' __ ' // ALTO ADIGE Deutsche Kultur das Amt der Südtiroler Landesregierung - Südtiroler Kulturinstitut Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie ; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. -

Primo Levi Cosí Fu Auschwitz Testimonianze 1945-1986 Con Leonardo De Benedetti

SUPER Di PRIMO LEVI (Torino 1919-1987) Einaudi ha Le verità piú precise – e inesorabili perché preci- «Attraverso i documenti fotografici e le pubblicato tutte le opere. Negli Einaudi Tasca- oramai numerose relazioni fornite da bili sono disponibili: Se questo è un uomo, La se – sulla macchina dello sterminio. Quarant’an- tregua, Il sistema periodico, La chiave a stella, ni di testimonianze, in gran parte inedite, di es- ex-internati nei diversi Campi di con- La ricerca delle radici. Antologia personale, Se senziale importanza storica. LEVI centramento creati dai tedeschi per l’an- non ora, quando?, L’altrui mestiere, I sommersi nientamento degli Ebrei d’Europa, forse e i salvati, Dialogo (con Tullio Regge), L’ultimo non v’è piú alcuno che ignori ancora che Natale di guerra e Tutti i racconti. Nel 1945, all’indomani della liberazione, i militari sovietici che COS cosa siano stati quei luoghi di sterminio controllavano il campo per ex prigionieri di Katowice, in Polo- e quali nefandezze vi siano state com- nia, chiesero a Primo Levi e a Leonardo De Benedetti, suo com- Í FU AUSCHWITZ piute. Tuttavia, allo scopo di far meglio pagno di prigionia, di redigere una relazione dettagliata sulle conoscere gli orrori, di cui anche noi sia- condizioni sanitarie del Lager. Il risultato fu il Rapporto su Au- mo stati testimoni e spesse volte vittime schwitz: una testimonianza straordinaria, uno dei primi reso- PRIMO LEVI durante il periodo di un anno, crediamo conti sui campi di sterminio mai elaborati. La relazione, pub- utile rendere pubblica in Italia una rela- blicata nel 1946 sulla rivista scientifica «Minerva Medica», zione, che abbiamo presentata al Gover- inaugura la successiva opera di Primo Levi testimone, analista COSÍ FU AUSCHWITZ no dell’U.R.S.S., su richiesta del Comando e scrittore. -

The Italian Supreme Court Decision on the Ferrini Case

The European Journal of International Law Vol. 16 no.1 © EJIL 2005; all rights reserved ........................................................................................... State Immunity and Human Rights: The Italian Supreme Court Decision on the Ferrini Case Pasquale De Sena* and Francesca De Vittor** Abstract In the Ferrini case the Italian Supreme Court affirmed that Germany was not entitled to sovereign immunity for serious violations of human rights carried out by German occupying forces during World War II. In order to reach this innovative conclusion, the Court widely referred to international legal arguments, such as the concept of international crimes, the principle of primacy of jus cogens norms and the notion of a strict analogy between state immunity and the ‘functional immunity’ of state officials. Based upon a systematic interpretation of the international legal order, the Court conducted a ‘balancing of values’ between the two fundamental international law principles of the sovereign equality of states and of the protection of inviolable human rights. This article explores the Court’s reasoning and its consistency with international legal theory and preceding case law with the view to verifying whether, and in which sense, the Ferrini judgment may facilitate a radical reappraisal of the relationship between human rights and the law of state immunity. 1 Introduction and Outline The recent judgment of the Italian Supreme Court (Corte di Cassazione) in Ferrini v. Federal Republic of Germany,1 which asserted Italian jurisdiction over Germany in a case * Professor of International Law, Second University of Naples. ** PhD in International Law, ‘Federico II’ University of Naples and ‘Robert Schuman’ University of Strasbourg. Sections 1, 6, 6A, 6B, and 7 were written by Pasquale De Sena; sections 2, 3, 4, and 5 were written by Francesca De Vittor. -

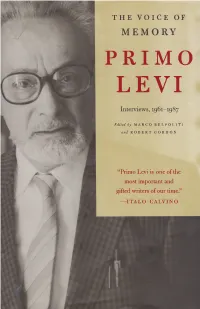

Primo-Levi-The-Voice-Of-Memory

THE VOICE OF MEMORY PRIMO LEVI Interviews, 1961-1987 Edited by M A R C 0 B E L P 0 L I T I and R 0 B E R T G 0 R D 0 N "Primo Levi is one of the most important and gifted writers of our time." -ITALO CALVINO The Voice of Memory The Voice of Memory Interviews 1961-1987 Primo Levi Edited by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon Translated by Robert Gordon The New Press New York This collection © 2001 by Polity Press First published in Italy as Primo Levi: Conversazioni e interviste 1963-87, edited by Marco Belpoliti © 1997 Guilio Einaudi, 1997, with the exception of the interviews beginning on pages 3, 13, 23, and 34 (for further details see Acknowledgments page). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. First published in the United Kingdom by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2001 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2001 Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York ISBN 1-56584-645-1 (he.) CIP data available. The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450West 41st Street, 6th floor, NewYork, NY 10036 www.thenewpress.com Set in Plantin Printed in the