Special Treatment in Auschwitz Origin and Meaning of a Term

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primo Levi and the Material World

Gerry Kearns1 If wood were an element: Primo Levi and the material world Abstract The precarious survival of a single shed from the Jewish slave labour quarters of the industrial complex that was Auschwitz- Monowitz offers an opportunity to reflect upon aspects of the materiality of the signs of the Holocaust. This shed is very likely ne that Primo Levi knew and its survival incites us to interrogate its materiality and significance by engaging with Levi’s own writings on these matters. I begin by explicating the ways the shed might function as an ‘encountered sign,’ before moving to consider its materiality both as a product of modernist genocide and as witness to the relations between precarity and vitality. Finally, I turn to the texts written upon the shed itself and turn to the performative function of Nazi language. Keywords Holocaust, icon, index, materiality, performativity, Primo Levi Fig. 1 - The interior of the shed, December 2012 (Photograph by kind permission of Carlos Reijnen) It is December 2012, we are near the town of Monowice in Poland. Alongside a small farmhouse, there is a hay-shed. The shed is in two parts with two doorways communicating and above these, “Eingang” and “Ausgang”. In the further part of the shed, there is more text, in Gothic font, in German. Along a crossbeam 1 National University of Ireland, Maynooth; [email protected]. I want to thank the directors of the Terrorscapes Project (Rob van der Laarse and Georgi Verbeeck) for the invitation to come on the field trip to Auschwitz. I want to thank Hans Citroen and Robert Jan van Pelt for their patient teaching about the history of the site. -

Primo Levi Cosí Fu Auschwitz Testimonianze 1945-1986 Con Leonardo De Benedetti

SUPER Di PRIMO LEVI (Torino 1919-1987) Einaudi ha Le verità piú precise – e inesorabili perché preci- «Attraverso i documenti fotografici e le pubblicato tutte le opere. Negli Einaudi Tasca- oramai numerose relazioni fornite da bili sono disponibili: Se questo è un uomo, La se – sulla macchina dello sterminio. Quarant’an- tregua, Il sistema periodico, La chiave a stella, ni di testimonianze, in gran parte inedite, di es- ex-internati nei diversi Campi di con- La ricerca delle radici. Antologia personale, Se senziale importanza storica. LEVI centramento creati dai tedeschi per l’an- non ora, quando?, L’altrui mestiere, I sommersi nientamento degli Ebrei d’Europa, forse e i salvati, Dialogo (con Tullio Regge), L’ultimo non v’è piú alcuno che ignori ancora che Natale di guerra e Tutti i racconti. Nel 1945, all’indomani della liberazione, i militari sovietici che COS cosa siano stati quei luoghi di sterminio controllavano il campo per ex prigionieri di Katowice, in Polo- e quali nefandezze vi siano state com- nia, chiesero a Primo Levi e a Leonardo De Benedetti, suo com- Í FU AUSCHWITZ piute. Tuttavia, allo scopo di far meglio pagno di prigionia, di redigere una relazione dettagliata sulle conoscere gli orrori, di cui anche noi sia- condizioni sanitarie del Lager. Il risultato fu il Rapporto su Au- mo stati testimoni e spesse volte vittime schwitz: una testimonianza straordinaria, uno dei primi reso- PRIMO LEVI durante il periodo di un anno, crediamo conti sui campi di sterminio mai elaborati. La relazione, pub- utile rendere pubblica in Italia una rela- blicata nel 1946 sulla rivista scientifica «Minerva Medica», zione, che abbiamo presentata al Gover- inaugura la successiva opera di Primo Levi testimone, analista COSÍ FU AUSCHWITZ no dell’U.R.S.S., su richiesta del Comando e scrittore. -

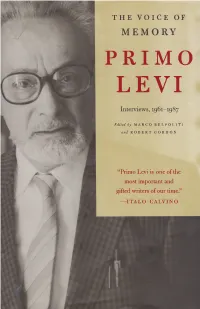

Primo-Levi-The-Voice-Of-Memory

THE VOICE OF MEMORY PRIMO LEVI Interviews, 1961-1987 Edited by M A R C 0 B E L P 0 L I T I and R 0 B E R T G 0 R D 0 N "Primo Levi is one of the most important and gifted writers of our time." -ITALO CALVINO The Voice of Memory The Voice of Memory Interviews 1961-1987 Primo Levi Edited by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon Translated by Robert Gordon The New Press New York This collection © 2001 by Polity Press First published in Italy as Primo Levi: Conversazioni e interviste 1963-87, edited by Marco Belpoliti © 1997 Guilio Einaudi, 1997, with the exception of the interviews beginning on pages 3, 13, 23, and 34 (for further details see Acknowledgments page). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. First published in the United Kingdom by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2001 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2001 Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York ISBN 1-56584-645-1 (he.) CIP data available. The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450West 41st Street, 6th floor, NewYork, NY 10036 www.thenewpress.com Set in Plantin Printed in the -

Historical Translatability

Historical Translatability Primo Levi Amongst the Snares of European History 1938– 1987 By Domenico S c a r p a (Turin) Taking his cue from the groundbreaking English translation of ›The Complete Works‹ of Primo Levi (recently published in America by Liveright) and focusing on Levi’s early writing, the author argues for the necessity of re-reading Primo Levi today, pleading for a new historical and chronological approach to his work. 1. I would like to begin with an explanation of the two dates in my subtitle, 1938 and 1987. 1938 is the year when the Fascist regime led by Mussolini passed rac- ist laws against Jews. This event not only put on Italian Jews the burden of an increasing self-consciousness, but it also marked the beginning of their “search for roots,” the construction of a cultural identity for the many of them who were not particularly religious or aware of their heritage or tradition. Primo Levi was himself such a secular Jew. More importantly, the racist laws of 1938 made Italian Jews aware of an im- pending catastrophe. 1938 brought about the recognition of a further dimen- sion in national and European history. Metaphorically speaking, 1938 broke the back of Italian historical continuity. Shattering Italian identity, it was the first of many fractures that were to occur in the decade to follow. There was the entry of Italy into World War II on June 10, 1940, the fall of the Fascist regime on July 25, 1943, the complete collapse and dissolution of the Italian state after the armistice with the Allies on September 8, 1943, the liberation and the victory of the Italian Resistance on April 25, 1945, the institution of the republic in 1946 and, finally, the writing and promulgation of the new constitution of the Repubblica Italiana in 1948. -

Commissione Parlamentare Di Inchiesta Sulle Cause Dell’Occultamento Di Fascicoli Relativi a Crimini Nazifascisti

CAMERA DEI DEPUTATI SENATO DELLA REPUBBLICA XIV LEGISLATURA Doc. XXIII N. 18 COMMISSIONE PARLAMENTARE DI INCHIESTA SULLE CAUSE DELL’OCCULTAMENTO DI FASCICOLI RELATIVI A CRIMINI NAZIFASCISTI (istituita con legge 15 maggio 2003, n. 107) (composta dai deputati: Tanzilli, Presidente; Verdini, Vicepresidente; Bocchino, Colasio, Segretari; Abbondanzieri, Arnoldi, Banti, Bondi, Carli, Damiani, Delmastro delle Vedove, Perlini, Raisi, Russo Spena, Stramaccioni, e dai senatori: Guerzoni, Vicepresidente; Brunale, Corrado, Eufemi, Falcier, Frau, Marino, Novi, Pellicini, Rigoni, Sambin, Servello, Vitali, Zancan, Zorzoli) RELAZIONE FINALE (Relatore: on. Enzo RAISI) Approvata dalla Commissione nella seduta dell’8 febbraio 2006 Trasmessa alle Presidenze delle Camere il 9 febbraio 2006, ai sensi dell’articolo 2, comma 4, della legge 15 maggio 2003, n. 107 STABILIMENTI TIPOGRAFICI CARLO COLOMBO Camera dei Deputati —2— Senato della Repubblica XIV LEGISLATURA — DISEGNI DI LEGGE E RELAZIONI — DOCUMENTI Camera dei Deputati —3— Senato della Repubblica XIV LEGISLATURA — DISEGNI DI LEGGE E RELAZIONI — DOCUMENTI PAGINA BIANCA Camera dei Deputati —5— Senato della Repubblica XIV LEGISLATURA — DISEGNI DI LEGGE E RELAZIONI — DOCUMENTI INDICE — Capitolo 1. Premessa ................................................................ Pag. 7 1.1. La legge istitutiva. L’articolo 1, commi1e2ela delimitazione dell’oggetto dell’inchiesta .................... » 7 1.2. Le attivita` di indagine (missioni e audizioni) e l’archivio della Commissione ...................................... » 8 1.3. Cenni sulle indagini precedentemente svolte (CMM 1999 – Commissione Giustizia della Camera dei deputati della XIII Legislatura 2001 – CMM 2005) e sui risultati conseguiti ................................................. » 31 1.4. Il metodo utilizzato e l’istruttoria espletata ............ » 33 1.5. Le Vittime e il valore della Memoria ...................... » 34 Capitolo 2. L’individuazione dei momenti rilevanti ............ » 36 2.1. La situazione italiana nel periodo post-bellico ...... -

Tedeschi, Italiani Ed Ebrei Le Polizie Nazi-Fasciste in Italia

Tedeschi, Italiani ed Ebrei Le polizie nazi-fasciste in Italia 1943-1945 1 2 Indice Introduzione, p.4 a) La polizia tedesca nel sistema di occupazione in Italia, p.7 Roma Milano Torino Genova Una visione d’insieme b) Il sistema repressivo italiano, p.26 c) Italiani e tedeschi nella prassi della persecuzione, p.35 Roma Milano Torino Como Genova Carceri e campi di concentramento Il ruolo dei vertici e dei militanti della RSI Il problema delle famiglie “miste” La reazione degli ebrei. d) Conclusioni, p.119 Documenti, p.125 Fonti e bibliografia, p. 3 “Io sono Eva. Sono su questo carro con mio figlio Abele. Se vedete l’altro mio figlio, Caino, figlio dell’uomo, ditegli che io…” Da una scritta ritrovata su un carro ferroviario tedesco. Introduzione Tra il 9 settembre 1943 ed il 2 maggio 1945, date di inizio e fine dell’occupazione tedesca, furono deportati (o uccisi) dall’Italia poco più di 8.000 ebrei, su una popolazione (compresi gli stranieri), di circa 47.000,1 una percentuale paragonabile a quella degli altri paesi dell’Europa occidentale, anche se l’Italia Centro settentrionale fu occupata per molto meno tempo. A Roma, ad esempio, i circa 750 ebrei catturati dopo la razzia del 16 ottobre 1943, furono presi in un arco di tempo di 7 mesi e mezzo: un periodo relativamente breve che conferma l’efficacia degli organi della SiPo-SD nella ex capitale del Regno, nonostante l’esiguo numero delle forze a disposizione. Lo scopo di questo saggio è di descrivere la prassi della persecuzione, per capire quali siano stati i metodi che hanno portato a risultati così tragicamente soddisfacenti per i persecutori. -

If This Is a Man Before If This Is a Man When Primo Levi Came Back to Italy in October 1945, He Has No Idea That Several Other T

If This Is a Man Before If This Is a Man When Primo Levi came back to Italy in October 1945, he has no idea that several other testimonies of former deportees like him had already been published. In the year that marked the official end of World War II, eleven books were published or printed by local publishers or presses. We do not know if Levi knew of any of these testimonies, as they were little more than pamphlets circulated locally. Only a few were distributed to bookstores. The first work to be published was by a chemist like Levi. Alberto Cavaliere was a member of the Communist Party who had told the story of his sister in law, Sofia Schafranov, a Jewish doctor of Russian origin. The title of the 92-page book published by Sonzogno in 1945 was I campi della morte in Germania: nel racconto di una soppravissuta (Death Camps in Germany: The Story of a Survivor). The second title to come out, an 82-page story by the writer and critic Giacomo De Benedetti had already been published in the journal ‘Mercurio’ in December 1944: 16 ottobre 1943 (October 16, 1943), published in Rome by OET. Neither Cavaliere nor Debenedetti had experienced the Lager first-hand, however. Gaetano De Martino, a Theosophist lawyer and militant communist was the first genuine eye-witness to publish his account alongside testimonies from other deportees. Published by Edizioni Alaya, the book was called Dal carcere di San Vittore ai “Lager Tedeschi”: sotto la sferza nazifascista (From San Vittore Prison to the “German Lager”: Under the Nazi-Fascist Whip). -

5. Leonardo Paggi, Ed., Storia E Memoria Di Un Massacro Ordinario

NOTES I Introduction 1. Egidio Cristini, "II massacro dei trecentoventi," recorded in Rome in 1957 by Roberto Leydi, in the CD Avanti Popo~6--Fischia il vento, lstituto Ernesto de Martino- Hobby&Work, 1998. Egidio Cristini was a construction worker and an improviser in the folk poetical tradition of the ottava rima, the eight-line stanza also used by Renaissance poets like Ludovico Ariosto and Torquato Tasso. 2. There never was any such thing as a "Badoglio-Communist." General Pietro Badoglio was prime minister in the king's government after Mussolini's overthrow and the removal of the king and his cabinet to Brindisi, in Southern Italy; the members of the military who stayed behind and were active in the Resistance were called "badogliani." They were monarchists, conservatives and anti-Communists. 3. The Fosse Ardeatine (or Cave Ardeatine as they were then known) were abandoned caves of pozzolana (a "finely divided siliceous or siliceous and aluminous material that reacts chemically with slaked lime at ordinary temperature and in the presence of moisture to form a strong hardening cement," ~bsters College Dictionary). It was used for the mak ing of cement and concrete during the construction boom of the 1880s in Rome. 4. Carlo Galante Garrone, "Via Rasella davanti ai giudici," in Priebke e il massacro delle Ardeatine, lstituto Romano per Ia Storia d'ltalia dal Fascismo alia Resistenza, supplement to l'Unita, August 1996. 5. Leonardo Paggi, ed., Storia e memoria di un massacro ordinario, Rome, Manifestolibri, 1996; Giovanni Contini, La memoria divisa, Milan, Rizzoli, 1996; Paolo Pezzino, Anato mia di un massacro, Bologne, II Mulino, 1997. -

Seduta Di Lunedi`6 Febbraio 2006

Atti Parlamentari —1—Camera Deputati – Senato Repubblica XIV LEGISLATURA — DISCUSSIONI — CRIMINI NAZIFASCISTI — SEDUTA DEL 6 FEBBRAIO 2006 COMMISSIONE PARLAMENTARE D’INCHIESTA SULLE CAUSE DELL’OCCULTAMENTO DI FA- SCICOLI RELATIVI A CRIMINI NAZIFASCISTI RESOCONTO STENOGRAFICO 78. SEDUTA DI LUNEDI` 6 FEBBRAIO 2006 PRESIDENZA DEL PRESIDENTE FLAVIO TANZILLI INDICE PAG. Sulla pubblicita` dei lavori: Tanzilli Flavio, Presidente .......................... 3 Seguito dell’esame della relazione conclusiva: Tanzilli Flavio, Presidente .......................... 3, 14 Raisi Enzo (AN), Relatore .......................... 3 ALLEGATO: Nuovo testo della proposta di relazione presentata dal relatore, onorevole Enzo Raisi .............................................................. 15 PAGINA BIANCA Atti Parlamentari —3—Camera Deputati – Senato Repubblica XIV LEGISLATURA — DISCUSSIONI — CRIMINI NAZIFASCISTI — SEDUTA DEL 6 FEBBRAIO 2006 PRESIDENZA DEL PRESIDENTE di inconfutabile livello: senza il loro ap- FLAVIO TANZILLI porto, non saremmo arrivati a tanto. Rin- grazio, altresı`, tutti i consulenti, perche´ La seduta comincia alle 20,15. hanno lavorato in modo encomiabile. Con alcuni di loro non ci siamo trovati d’ac- (La Commissione approva il processo cordo su determinate tesi, ma e` indiscu- verbale della seduta precedente). tibile la loro volonta` di collaborare nel- l’interesse della Commissione e per l’ac- certamento della verita`. Credo sia un rin- Sulla pubblicita` dei lavori. graziamento dovuto e, almeno questo, da tutti condiviso. PRESIDENTE. Avverto che, ai sensi Ringrazio anche il presidente con il quale dell’articolo 5, comma 1, della legge n. 107 ogni tanto ho avuto uno scambio di vedute del 2003 e dell’articolo 11, comma 1, del non sempre condivise, ma fa parte... regolamento interno, la Commissione de- libera di volta in volta quali sedute o parti PRESIDENTE. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 . Primo Levi, Se questo è un uomo (Torino: F. de Silva, 1947) and Survival in Auschwitz: The Nazi Assault on Humanity (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996). 2 . Robert S. Gordon, “Which Holocaust? Primo Levi and the Field of Holocaust Memory in Post-War Italy,” Italian Studies , Vol. 61 (Spring 2006), pp. 85–113. 3 . L e v i , Survival in Auschwitz , p. 87. 4 . I b i d . 5 . Ibid., 92. 6 . Primo Levi, The Drowned and the Saved (New York: Summit Books, 1988), p. 37. 7 . Ibid., p. 39. 8 . Ibid., p. 42. 9 . Ibid., p. 53. 10 . Historian Robert Gordon argues that “Holocaust” is a problematic term in Italy because it includes victims groups beyond those targeted for geno- cide, such as civilians killed during the German occupation of Italy and Italian resistors. Thus, I chose to use “Judeocide” here to speak specifically to Jewish victims. Gordon, “Which Holocaust,” p. 92. 11 . Unless otherwise noted, I will refer to the camp built in Fossoli, a township of Carpi, by the town name. 1 2 . R a u l H i l b e r g , Perpetrator Victims Bystanders: The Jewish Catastrophe, 1933–1945 (New York: Aaron Asher Brooks, 1992), pp. 212–216. 13 . Robert Ehrenreich and Tim Cole, “The Perpetrator-Bystander-Victim Constellation; Rethinking Genocidal Relationships,” Human Organization , Vol. 64, No. 3 (2005), p. 218. 14 . Arne Johan Vetlesen, “Genocide: A Case for the Responsibility of the Bystander,” Journal of Peace Research , Vol. 37, No. 4, Special Issue on Ethics of War and Peace (July 2000), p. -

Professor of History Queensboro UNICO Distinguished Professor of Italian & Italian American Studies Fellow, Hofstra Cultura

STANISLAO G. PUGLIESE, PH.D. Professor of History Queensboro UNICO Distinguished Professor of Italian & Italian American Studies Fellow, Hofstra Cultural Center Hofstra University Hempstead, New York 11549 USA 516.463.5611 [email protected] Web page: http://people.hofstra.edu/faculty/Stanislao_Pugliese/ Fulbright Scholar, University of Calabria, CLIA Program, Spring 2020 Visiting Scholar, Center for European and Mediterranean Studies, NYU, 2014-15 Visiting Scholar, Istituto Campano per la Storia della Resistenza, Naples, Fall 2010 Visiting Scholar, Harvard University, Romance Languages & Literature, Spring 2010 Visiting Research Fellow, University of Oxford, June 2004 Visiting Scholar, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. June 2003 Visiting Research Fellow, Italian Academy, Columbia University, Spring 2001 EDUCATION Ph.D. Modern European History, City University of New York Graduate School, 1995. M.A. in Modern European History, City College of New York, 1990. Certificato di Studio, Modern Italian Political History, Università degli Studi di Firenze, 1988. B.A. University Honors Degree in History & Philosophy, Hofstra University, 1987. Phi Beta Kappa & Phi Alpha Theta TEACHING Fall 2009-present Distinguished Professor, Hofstra University Fall 2004-present Professor of History, Hofstra University Fall 2000-August 2004 Associate Professor of History, Hofstra University Fall 1995-Spring 2000 Assistant Professor of History, Hofstra University Fall 1994-Spring 1995 Instructor in History, Hofstra University -

Mandr June.Qxp

Vol. 33-No.5 ISSN 0892-1571 May/June 2007-Sivan/Tammuz 5767 ver 200 people attended the American Society for Yad Vashem Annual Spring American and International Societies for Yad Vashem. Gladys’s involvement in OLuncheon, in tribute to a Woman’s Legacy: Not by Might, Not by Power, But philanthropic causes and her efforts to enhance the lives of the Jewish people, with Love, held on Thursday, May 3, 2007 at the Park Avenue Synagogue. This both in the United States and Israel, is seen through her support of Israel Bonds, year’s Luncheon was made especially meaningful by the active participation of Yad Vashem, American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), Jewish National many members of the third generation, who expressed their commitment to carry Fund (JNF), Hadassah and numerous other American and Israeli Jewish organizations. the torch for the Legacy of Remembrance. Adina Shainker Burian, Young Rita Levy of Roslyn, New York was presented with an award recognizing her ded- Leadership Associate Board Member and this year’s Spring Luncheon ication to Remembering the Past and her commitment to use her creative talents Chairperson, led the way for members of this new group. to further Holocaust Awareness and Education by Julie Schwartz Kopel, a Young Yonina Gomberg, granddaughter of Gladys Halpern and member of the third gen- Leadership Associate Board Member and member of the third generation. eration, introduced Gladys Halpern of Hillside, New Jersey, who received an award Mrs. Levy is deeply committed to Israel, Holocaust Remembrance and Jewish recognizing her Resistance and Courage in the Face of the Holocaust and her cultural preservation.