Directing Wild Honey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drama Audition Female Senior Monologues

Drama Audition Female Senior Monologues Northmead Creative & Performing Arts High School NSW, Department of Education and Training N S W , Classical and contemporary audition pieces. Department of Education and T r a i n i n g Imagine, Endeavour, A c h i e v e Northmead CAPAHS Campbell Street Northmead N S W 2 1 5 2 02 96304116 P r i n c i p a l – N . V a z q u e z Northmead Creative & Performing Arts High- Drama Audition The following pieces have been chosen from standard editions of the works. You may use the equivalent monologue from a different edition of the play, for example, if you have access to a different edition of the Shakespeare plays. For translated works, we have chosen a particular translation. However, you may use another translation if that is the version available to you. If you cannot access the Australian plays through your local library, bookshop or bookshops on our suggested list, published editions of the Australian plays are generally available through Currency Press. AUDITION PROCESS You will be required to choose one monologue from the list provided to perform. Please note the delivery time of a monologue may vary depending on your interpretation of the chosen piece. Usual estimated time is between three to eight minutes. So please make sure your monologue is within this time frame. You may be asked to deliver your chosen piece more than once. You will also be tested for improvisation skills. So be prepared to use your imagination and creativity. A script may be handed to you during the audition. -

EDUCATION PACK 1 Bristol Old Vic | the Cherry Orchard | Education Pack “A Poem About Life and Death and Transition and Change” PETER BROOK, 1981

EDUCATION PACK 1 Bristol Old Vic | The Cherry Orchard | Education Pack “A poem about life and death and transition and change” PETER BROOK, 1981 FOREWORD CONTENTS The Cherry Orchard was written over a hundred 2. Introduction years ago and the dominant issue of anxiety and 3. Chekhov, A History change are still with us in a tumultuous twenty-first century. As teachers, we are in a position where we 5. Exploring the Story can challenge ideas and stimulate discussion within 7. Dissecting the Characters our classrooms while exploring a wide range of performance opportunities. This is a play where 9. A Note from the Director seemingly very little happens on stage but events of 11. A Note from the Designer rapid economic and cultural change are happening all around. We know the old way of life is doomed 13. The Moscow Arts Theatre but are not sure whether the new dawn will 14. Under the Microscope ultimately be any better than that which is being cast aside. 15. Key Themes This is a play of many contradictions and is wide 16. How to Write a Review open to a director’s interpretation. Does the future 17. Activities look bleak or alluring? Chekhov wrote The Cherry Orchard while he was dying and knew that this would be his last play. Does this create an air of melancholy? How does this sit with the conjuring tricks and circus skills in this self-declared ‘comedy in four acts’? Is it a naturalistic or symbolic play or a combination of the two? We can decide on any one or all of these interpretations and each are as Introduction valid as any other. -

A Companion to Andrei Platonov's the Foundation

A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Studies in Russian and Slavic Literatures, Cultures and History Series Editor: Lazar Fleishman A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Thomas Seifrid University of Southern California Boston 2009 Copyright © 2009 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-934843-57-4 Book design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2009 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com iv Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE Platonov’s Life . 1 CHAPTER TWO Intellectual Influences on Platonov . 33 CHAPTER THREE The Literary Context of The Foundation Pit . 59 CHAPTER FOUR The Political Context of The Foundation Pit . 81 CHAPTER FIVE The Foundation Pit Itself . -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Reclaiming Native Soil: Cultural Mythologies of Soil in Russia and Its Eastern Borderlands from the 1840s to the 1930s Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/74g4p86x Author Erley, Laura Mieka Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Reclaiming Native Soil: Cultural Mythologies of Soil in Russia and Its Eastern Borderlands from the 1840s to the 1930s by Laura Mieka Erley A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Irina Paperno, Chair Professor Olga Matich Professor Eric Naiman Professor Jeffrey Skoller Fall 2012 Reclaiming Native Soil: Cultural Mythologies of Soil in Russia and its Eastern Borderlands from the 1840s to the 1930s © 2012 by Laura Mieka Erley Abstract Reclaiming Native Soil: Cultural Mythologies of Soil in Russia and Its Eastern Borderlands from the 1840s to the 1930s By Laura Mieka Erley Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Irina Paperno, Chair This dissertation explores the cultural topos of soil in Russian and early Soviet culture. Centered on the Soviet project of land reclamation in Central Asia in the 1930s, this dissertation traces the roots of Soviet utopian and dystopian fantasies of soil to the ideological and discursive traditions of the 19th century. It considers how Soviet cultural, scientific, and political figures renovated and adapted 19th-century discourse in order to articulate for their own age the national, revolutionary, and utopian values attached to soil. -

The Seagull(1896)

Summer 1, 2021 GBS Theatre The Seagull (1896) by Anton Chekhov adapted by Joan Oliver Cast (in alphabetical order) Creative Team Simon Medvedenko Director Ian Bouillion Joan Oliver Eugene Dorn Designer Dylan Corbett-Bader Louis Carver Masha Russian Translator and Literary Advisor Florence Dobson Viktorija Rasciauskaite Boris Trigorin Associate Designer Raphel Famotibe Anita Gander Irina Arkadina Lighting Designer Elizabeth Hollingshead Amy Mae Konstantin Associate Lighting Designer Gabriel Howell Ollie Morrill Paulina Sound Designer Megan Langford Dylan Marsh Nina Cellist Aliyah Odoffin Elizabeth Hollingshead Ilia Shamrayev Movement Coach Samuel Tracy Mixalis Aristidou Peter Sorin Voice and Dialect Coach Benjamin Westerby Deborah Garvey Fight Coach Bret Yount Student Production Team Production Manager Radio Mic Runner Scenic Art Assistants Sam Kelly Abraham Walkling-Lea Jordan Deegan-Fleet Roma Farnell Technical Manager Broadcast Lucinda Plummer Jack Hollingsworth Andrea Scott Spiky Saul Stage Manager Sound Crew Props Maker Rosa Watson Alfie Sissons Pip Beattie Daberechi Ukoha-Kalu Deputy Stage Manager Abraham Walkling-Lea Props Assistants Jaimie Wakefield Isabelle Whitehill Aidan O’Sullivan Sylvia Wan Assistant Stage Manager Construction Project Manager Thomas Fielding Jeff Bruce-Hay (RADA Staff) Show Crew Alfie Sissons ASM 2s Assistant Construction Project Daberechi Ukoha-Kalu Aidan O’Sullivan Manager Abraham Walkling-Lea Sylvia Wan Joel Mansi Thomas Isabelle Whitehill Chief Electrician Scenery Builders Special thanks: Sammy Emmins Alice -

Round Lake Elementary Schoo

Round Lake Elementary School - 2007 Accelerated Reader List - By Title http://www.lakeline.lib.fl.us/resources/accelerated_reading_lists/html/R... Round Lake Elementary School 2007 Accelerated Reader List - By Title Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 48028 EN 100-Pound Problem, The Dussling, Jennifer 2.5 0.5 17351 EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Baseball Italia, Bob 5.5 1.0 17352 EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Basketball Italia, Bob 6.5 1.0 17353 EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Football Italia, Bob 6.2 1.0 17354 EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Golf Italia, Bob 5.6 1.0 17355 EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Hockey Italia, Bob 6.1 1.0 17356 EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Tennis Italia, Bob 6.4 1.0 17357 EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Summer Olympics Italia, Bob 6.5 1.0 17358 EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Winter Olympics Italia, Bob 6.1 1.0 18751 EN 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Wardlaw, Lee 3.9 5.0 14796 EN 13th Floor: A Ghost Story, The Fleischman, Sid 4.4 4.0 67305 EN 17 Kings and 42 Elephants Mahy, Margaret 3.7 0.5 8251 EN 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda Lee 5.2 1.0 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 15903 EN 19th Century Girls and Women Kalman, Bobbie 5.5 0.5 103480 2 Good 2 B True Alfonsi, Alice 4.4 2.0 EN 7351 EN 20,000 Baseball Cards under the Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 11592 EN 2095 Scieszka, Jon 3.8 1.0 6201 EN 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue De Paola, Tomie 4.4 1.0 68113 EN 3, 2, 1 Go! A Transportation Countdown Schuette, Sarah L. -

The Cambridge Companion to Chekhov Edited by Vera Gottlieb and Paul Allain Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521581176 - The Cambridge Companion to Chekhov Edited by Vera Gottlieb and Paul Allain Index More information INDEX OF WORKS BY CHEKHOV Aga®a 4, 9 Conspirator, The 9 Anna on My Neck 149±50 Anniversary, The Esee also Jubilee) 58, 66, Daughter of Albion, The 149, ®lm, and see 166, 236 also Appendix 1 Ariadna 205, 207 Dark Eyes E®lm) 154 and see Appendix 3 At a Country House 51 Dead Body, A 9 At Dusk 10 Death of a Clerk, The /Death of a Petty August E®lm adaptation of Uncle Vanya Of®cial 8, 150 directed by Anthony Hopkins ± see also Disturbing the Balance 211 Uncle Vanya) 158±9 Don Juan Bin the Russian Manner) Esee also Platonov)48 Bear, The/The Boor 7, 10, 57±8, 59, 61, 62, Duel, The 9, 10, 206, 208, 211 63, 65, 66, 68 n.9, 100 n.3, 162, 163, 166 Dreary Story, A 7, 23, 204, 205, 206, 208, Belated Blossom/Late Blossoms/The Flowers 209 are Late 7, 112, 149 Big Volodia and Little Volodia 210 Easter Eve 9 Bishop, The 9, 13, 204 Enemies, The 9 Black Monk, The 7, 26, 208 Bride, The/The FianceÂe/The Marrigeable Girl Fat and Thin 7, 8 24, 211 Fatherlessness Esee also Platonov) 43, 47, 163 Burbot, The 208 Fireworks on the James Esee also Platonov) 48 Cases of Mania Grandioza 20 Fortune 205, 212 Chameleon/A 6, 8, 150 Fragments/Fragments of Moscow Life Children 9 BOskolki) 6, 9, 228 Cherry Orchard, The xxii Eillus.), xxx, xxxiii, 7, 13, 14, 18, 22, 24±5, 29, 30, 31, 55, 55 Gloomy People 10 n.3, 59, 60, 62, 63±4, 65, 66, 68 ns.5, 9 Grasshopper, The 153, 207 and 11, 69 n.19, 91, 93, 95, 97, 104, 108, Gusev 4, 10 109 n.6, 110 -

Metrodogs: the Heart in the Machine

MetroDogs: the heart in the machine Alaina Lemon University of Michigan Dogs in the Moscow Metro, some say, have evolved a unique sentience: they navigate a human-scaled infrastructure and interpret human motives there. Such assertions about dogs, and encounters with them on public transit, invoke Soviet-era moral projects that wove sentiment (‘compassion’) and affect (‘attention’) through technical dreams: to erase material suffering and physical violence, to traverse the globe and the cosmos, to end wars and racisms. Dogs, after all, helped defeat the Nazis and took part in the space race. In the Metro now, their wags and barks stir debate about access and exclusion, resonating across assemblages of materials and meanings, social connections and signs. MetroDogs invite us to theorize the ways people extend connections in the moment well beyond the here-and-now. Super-smart dog mutants have appeared in Moscow, explaining themselves with gestures. Novosti Rossii, 14 October 2004 Dogs have learned to ride the Moscow Metro escalators. Inhabitants have documented this on the Internet, posting videos of dogs who wait for trains and curl up on car bench seats. Moscow’s leading canine experts stress the dogs’ strategic virtuosity as they slip between car doors just as they slam shut: MetroDogs entertain themselves in quite an original way. They love to jump through the closing doors of electric train cars. Just in time, so that their tails might get pinched! Zoologists say that this striving towardsextremesarisesfromsatiation.Justasitdoesinpeople,incidentally(Komsomol’skaja Pravda, 20 May 2008). For Muscovites, it is an enviable virtuosity: they may know their Metro as the most efficient, most beautiful in the world, but they also know that its automated car doors smash together even before the recording finishes warning passengers (Lemon 2009a). -

Acting III THR 369.2 Continuing the Exploration

MWF 10:00-10:50am Tom Prior, Instructor Fall 2007 Email: [email protected] Office hours: MWF by appt. Phone: (936) 294-1328 Office Location: UTC-112 Class Location: UTC-151 Acting III THR 369.2 Continuing the Exploration THIS SYLLABUS, SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION, ANNOUNCEMENTS AND GRADES CAN BE FOUND ON THE BLACKBOARD WEBSITE-PLEASE CHECK IT FREQUENTLY! http://blackboard.shsu.edu Class objective: To explore the skills and tools necessary for advanced scene work. We will be using the works of Anton Chekhov and Tennessee Williams during the semester, supplemented with various exercises. These exercises are designed to lead to the understanding of more advanced concepts and techniques of the acting process. Using Michael Shurtleff’s book Audition, we will continue more advanced work on the moment before, intentions/motivation of character, listening on-stage and making strong and creative choices. Additionally, we will be delving into monologue work, increasing the student’s repertoire. Required Text: Audition…………………………………….Michael Shurtleff On Reserve in Library: Uncle Vanya …………………………………Anton Chekhov Wild Honey…Michael Frayn (adaptation of Platonov by Anton Chekhov) The Seagull…………………………………..Anton Chekhov Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (and one TBA) …Tennessee Williams I may be adding additional texts, which I will also place on reserve. Classroom Attire: Please wear clothes that you feel comfortable moving in. Loose fitting clothing such as sweatpants and T-shirts are best. Classroom Etiquette: This class is a CELL PHONE AND PAGER FREE ZONE!! Turn them off when you walk through the door!! Attendance: Please be here on time ready to work. -

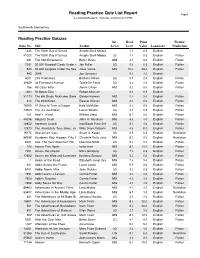

Rpquiz List Report Preview

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Thursday, 03/04/10, 02:15 PM Southworth Elementary Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 1235 The 100th Day of School Angela Shelf Medearis 1.5 0.5 English 41025 The 100th Day of School Angela Shelf Medearis LG 1.4 0.5 English Fiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.1 3.0 English Fiction 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the JonSea Buller LG 2.6 0.5 English Fiction 523 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged)Jules Verne MG 10.0 28.0 English Fiction 992 2095 Jon Scieszka 5.0 1.0 English 6201 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen LG 3.1 2.0 English Fiction 30629 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola LG 4.4 1.0 English Fiction 166 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson MG 5.2 5.0 English Fiction 1223 50 Below Zero Robert Munsch 2.8 0.5 English 31170 The 6th Grade Nickname Game Gordon Korman MG 4.4 3.0 English Fiction 413 The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson MG 4.3 2.0 English Fiction 76205 97 Ways to Train a Dragon Kate McMullan MG 3.3 2.0 English Fiction 79509 The A+ Custodian Louise Borden LG 4.5 0.5 English Fiction 101 Abel's Island William Steig MG 6.2 3.0 English Fiction 44236 Abigail's Drum John A. Minahan MG 4.6 1.0 English Fiction 18652 Abraham Lincoln Ingri/Edgar Parin D'AulaireLG 5.2 1.0 English Fiction 12573 The Absolutely True Story...How WilloI Visited Davis Yellowstone.. -

In This Is the End of Sleeping

The Chekhov Now Festival, in collaboration with ROTOR Productions, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology PRESENTS: IN THIS IS THE END OF SLEEPING After the Platonov fragment by CHEKHOV directed by JAY SCHEIB video and sound by LEAH GELPE, stage and light by JEREMY MORRIS, costumes by JESSICA HINEL, objects/art direction by BARA JICHOVA KIRKPATRICK, assistant director ADAM PERLMAN, stage managed by BELINA MIZRAHI, adapted and directed by JAY SCHEIB With performances by Eliza Bent, Gaëtan Bonhomme, Vanessa Burke, John Dewis, Olga Victorovna Fedorishcheva, Caleb Hammond, Joan Jubett*, Emily Knapp, Dan Liston, Eric Dean Scott*, Tao Wang * COURTESY OF ACTORS EQUITY, AEA SHOWCASE APPROVED Performances In New York City, as part of the Chekhov Now Festival: Opens Friday, Nov 12 at 8pm—and runs Nov 13 at 8pm; Nov 14 at 2pm; Nov 17 at 8pm; Nov 18 at 8pm; and Nov 20 at 5pm At the Connelly Theatre, 220 East 4th Street Tickets for the Chekhov Now Festival: 212.352.3101 or www.theatremania.com www.rotorproductions.com Anton Chekhov 1860-1904 About the Company (cont.) Adapted from the "Index of Chekhov productions" in Laurence Senelick’s book The Chekhov Theatre Joan Jubett (Anna Voynitsev) NEW YORK: Mac Wellman’s reading of School for Devils chronology (Primary Stages, Dir. Ken Rus Schmoll), co-author and performer with Jerusha 1860 Anton Chekhov born to the son of a former serf (now a grocer) Klemperer in Ritalin for Two (UNDER St. Marks, Dir. Rosemary Andress), Koltès’ Battle 1879 Chekhov enrolls in the Moscow University Medical school of Black and Dogs (Ohio Theatre, KoltèsNY2003 Festival, Dir. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography Editions of Chekhov’s plays and short stories consulted or cited Bentley, E., ed. and trans., The Brute and Other Farces by Anton Chekhov, Grove Press, New York, 1958. Bristow, E. K., trans. and ed., Anton Chekhov's Plays, W. W. Norton and Com- pany, New York, 1977. Chekhov, A. (unknown translator), The Plays of Anton Chekhov, J. J. Little and Ives Company, New York, 1935. Chekhov, A. (unknown translator), The Cherry Orchard, Dover Publications, New York, 1991. Dunnigan, A., Chekhov: The Major Plays, The New America Library, New York, 1964. Fell, M. and West, J., trans., Tchekoff: Six Famous Plays, Gerald Duckworth and Co., London, 1949. Fen, E., ed., Chekhov Plays, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1954. Frayn, M., trans., Wild Honey, Methuen, London, 1984. Frayn, M., trans., Chekhov Plays, Methuen Drama, London, 1988. Frayn, M., trans., The Seagull, Allen & Unwin, London, 1989. Gems, P., Uncle Vanya: A New Version, Eyre Methuen, London, 1980. Griffiths, T., ed., The Cherry Orchard, new English version, from Rapaport, H., trans., Pluto Press, London, 1981. Guthrie, T. and Kipnis, L., trans., The Cherry Orchard, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1965. Hingley, R., The Oxford Chekhov, Vol. 1, Short Plays, Oxford University Press, London, 1968. Hingley, R., The Oxford Chekhov, Vol. 2, Platonov, Ivanov, The Seagull, Oxford University Press, London, 1967. Hingley, R., The Oxford Chekhov, Vol. 3, Uncle Vanya, Three Sisters, The Cherry Orchard, The Wood Demon, Oxford University Press, London, 1964. Hingley, R., The Oxford Chekhov, Vol. 4, Stories 1888±1889, Oxford University Press, London, 1980. Hingley, R., The Oxford Chekhov, Vol. 5, Stories 1889±1891, Oxford University Press, London, 1970.