Metrodogs: the Heart in the Machine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mad-Cow’ Worries Intensify Becoming Prevalent.” Institute

The National Livestock Weekly May 26, 2003 • Vol. 82, No. 32 “The Industry’s Largest Weekly Circulation” www.wlj.net • E-mail: [email protected] • [email protected] • [email protected] A Crow Publication ‘Mad-cow’ worries intensify becoming prevalent.” Institute. “The (import) ban has but because the original diagnosis Canada has a similar feed ban to caused a lot of problems with our was pneumonia, the cow was put Canada what the U.S. has implemented. members and we’re hopeful for this on a lower priority list for testing. Under that ban, ruminant feeds situation to be resolved in very The provincial testing process reports first cannot contain animal proteins be- short order.” showed a possible positive vector North American cause they may contain some brain The infected cow was slaugh- for mad-cow and from there the and spinal cord matter, thought to tered January 31 and condemned cow was sent to a national testing BSE case. carry the prion causing mad-cow from the human food supply be- laboratory for a follow-up test. Fol- disease. cause of symptoms indicative of lowing a positive test there, the Beef Industry officials said due to pneumonia. That was the prima- test was then conducted by a lab Canada’s protocol regarding the ry reason it took so long for the cow in England, where the final de- didn’t enter prevention of mad-cow disease, to be officially diagnosed with BSE. termination is made on all BSE- food chain. they are hopeful this is only an iso- The cow, upon being con- suspect animals. -

Selecting a Livestock Guardian Dog Puppy

University of California Cooperative Extension Livestock Protection Tools Fact Sheets Number 5 Selecting a Livestock Guardian Dog Puppy By Dan Macon, Livestock and Natural Resources Advisor (Placer-Nevada-Sutter-Yuba) and Carolyn Whitesell, Human- Wildlife Interactions Advisor (San Mateo-San Francisco) Adapted from “How to Select an LGD Puppy” by Bill Constanzo, Livestock Guardian Dog Research Specialist, Texas A&M AgriLife Center Overview Puppy selection is often the critical first step towards successfully using livestock guardian dogs (LGDs) in a production setting. While appropriate bonding during the first 12-18 months of a dog’s life is important, pups with an inherent genetic predisposition for guarding livestock are more likely to become successful adult LGDs. Furthermore, physical traits (like hair coat, color, mature size, etc.) are preset by a pup’s genetics. Keep in mind that LGD behaviors are greatly influenced by how they are treated during the first year of their life. This fact sheet will help you select an LGD pup that will most likely fit your particular needs. Buy a Pup from Reputable Genetics: Purchasing a pup from working parents will increase the likelihood of success. A knowledgeable breeder (who may also be a livestock producer) will know the pedigree of his or her pups, as well as the individual behaviors of the parents. While observation over time is generally more reliable than puppy aptitude testing, you should still try to observe the pups, as well as the parents, in their working setting. Were the pups whelped where they could hear and smell livestock before their eyes were open? What kind of production system (e.g., open range, farm flock, extensive pasture system, etc.) do the parents work in? If you cannot observe the pups in person before purchasing, ask the breeder for photos and/or videos, and ask them about the behavioral traits discussed below. -

Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story

Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story Edited by Oriana Palusci Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story Edited by Oriana Palusci This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Oriana Palusci and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0353-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0353-3 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Alice Munro’s Short Stories in the Anatomy Theatre Oriana Palusci Section I: The Resonance of Language Chapter One ............................................................................................... 13 Dance of Happy Polysemy: The Reverberations of Alice Munro’s Language Héliane Ventura Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 27 Too Much Curiosity? The Late Fiction of Alice Munro Janice Kulyk Keefer Section II: Story Bricks Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 45 Alice Munro as the Master -

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

ILLINO S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. THE BULLETIN OF THE CENTER FOR CHILDREN'S BOOKS JULY/AUGUST 1992 VOLUME 45 NUMBER 11 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS EXPLANATION OF CODE SYMBOLS USED WITH ANNOTATIONS * Asterisks denote books of special distinction. R Recommended. Ad Additional book of acceptable quality for collections needing more material in the area. M Marginal book that is so slight in content or has so many weaknesses in style or format that it should be given careful consideration before purchase. NR Not recommended. SpC Subject matter or treatment will tend to limit the book to specialized collections. SpR A book that will have appeal for the unusual reader only. Recommended for the special few who will read it. C.U. Curricular Use. D.V. Developmental Values. THE BULtum OF THE CENTER PO CmLDREN'S BOOKs (ISSN 0008-9036) is published monthly except August by The University of Chicago Press, 5720 S. Woodlawn, Chicago, Illinois, 60637 for The Centeor Children's Books. Betsy Hearnm Editor; Roger Sutton Executive Editor; Zena Sutherland, Associate Editor, Deborah Stevenson, Editorial Assistant. An advisory committee meets weekly to discuss books and reviews. The members are Alba Endicott, Robert Strang, Elizabeth Taylor, Kathryn Jennings, and Deborah Stevenson. Reviewers' initials are appended to reviews. SUBSCRI RATES:•oN 1 year, institutions, $32.00; individuals, $27.00; $24.00 per year for two or more subscriptions to the same address; Canada, $39.24. In countries other than the United States and Canada, add $5.00 per subscription for postage. -

March 22, 2018

Packer Lambs Steady To Mostly Lower San Angelo slaughter lamb prices were $10-20 lower this week, feeder lambs steady. Goldthwaite wool lambs were $5 lower, light Dorper and Bar- bado lambs $5-10 lower, and medium and heavy hair lambs steady to $5 lower. Hamilton lambs sold steady. Fredericks- burg lambs were $5 lower. VOL. 70 - NO. 11 SAN ANGELO, TEXAS THURSDAY, MARCH 22, 2018 LIVESTOCKWEEKLY.COM $35 PER YEAR Lamb and mutton meat production for the week end- ing March 16 totaled three million pounds on a slaugh- ter count of 40,000 head compared with the previous week’s totals of 3.1 million pounds and 42,000 head. Imported lamb and mutton for the week ending March 10 totaled 2553 metric tons or approximately 5.63 million pounds, equal to 182 percent of domestic production for the same period. San Angelo’s feeder lamb market had medium and large 1-2 newcrop lambs weighing 40-60 pounds at $200-206, 60-90 pounds $192-218, 80- 100 pounds $192-218, oldcrop 60-90 pounds $184-196, and 100-105 pounds $166-172. Fredericksburg No. 1 wool lamb weighing 40-60 pounds were $200-240 and 60-80 pounds $200-230. Hamil- ton Dorper and Dorper cross lambs weighing 20-40 pounds sold for $180-260. Direct trade on feeder lambs last week was limited to Colo- rado, where 400 head weighing SOCIAL WARRIORS may take offense, but males-only 125-135 pounds brought $168. enclaves are still common in the livestock business. San Angelo choice 2-3 Whether bucks, bulls or billies, the Old Boys’ clubs are slaughter lambs weighing Range Sales a fi xture much of the year, giving way only during breed- 110-170 pounds brought ing season, itself a highly non-PC concept. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

FULL LIST of WINNERS the 8Th International Children's Art Contest

FULL LIST of WINNERS The 8th International Children's Art Contest "Anton Chekhov and Heroes of his Works" GRAND PRIZE Margarita Vitinchuk, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “The Lucky One” Age Group: 14-17 years olds 1st place awards: Anna Lavrinenko, aged 14 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Ward No. 6” Xenia Grishina, aged 16 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chameleon” Hei Yiu Lo, aged 17 Hongkong for “The Wedding” Anastasia Valchuk, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Ward Number 6” Yekaterina Kharagezova, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Portrait of Anton Chekhov” Yulia Kovalevskaya, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Oversalted” Valeria Medvedeva, aged 15 Serov, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia for “Melancholy” Maria Pelikhova, aged 15 Penza, Russia for “Ward Number 6” 1 2nd place awards: Anna Pratsyuk, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “Fat and Thin” Maria Markevich, aged 14 Gomel, Byelorussia for “An Important Conversation” Yekaterina Kovaleva, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “The Man in the Case” Anastasia Dolgova, aged 15 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Happiness” Tatiana Stepanova, aged 16 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Kids” Katya Goncharova, aged 14 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chekhov Reading Out His Stories” Yiu Yan Poon, aged 16 Hongkong for “Woman’s World” 3rd place awards: Alexander Ovsienko, aged 14 Taganrog, Russia for “A Hunting Accident” Yelena Kapina, aged 14 Penza, Russia for “About Love” Yelizaveta Serbina, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Chameleon” Yekaterina Dolgopolova, aged 16 Sovetsk, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia for “The Black Monk” Yelena Tyutneva, aged 15 Sayansk, Irkutsk Oblast, Russia for “Fedyushka and Kashtanka” Daria Novikova, aged 14 Smolensk, Russia for “The Man in a Case” 2 Masha Chizhova, aged 15 Gatchina, Russia for “Ward No. -

Personality Development of Grigory Stepanovitch Smirnov in the Bear Drama by Anthon Chekhov (1888): an Individual Psychological Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UMS Digital Library - Selamat datang di UMS Digital Library PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT OF GRIGORY STEPANOVITCH SMIRNOV IN THE BEAR DRAMA BY ANTHON CHEKHOV (1888): AN INDIVIDUAL PSYCHOLOGICAL APPROACH PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department by: DARMAWAN ROSADI A 320 080 124 SCHOOL OF TEACHING TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2015 1 PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT OF GRIGORY STEPANOVITCH SMIRNOV IN THE BEAR DRAMA BY ANTHON CHEKHOV (1888): AN INDIVIDUAL PSYCHOLOGICAL APPROACH Darmawan Rosadi Dewi Candraningrum Titis Setyabudi School of Teacher Training and Education Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta ABSTRACT The object of the research is the drama entitled The Bear by Anthon Chekhov. The major problem of this study is how personality development influences the major character, Grigory Stepanovitch Smirnov, in Anthon Chekhov’s The Bear. It is aimed to analyze the drama based on individual psychological approach by Alfred Adler. The type of the study is qualitative research. There are two data sources that the researcher uses, the primary data sources and secondary data sources. The primary data source is the drama itself and the secondary data sources are any information related to study and other books which deal with the study. The techniques of data collection are documentations and library research. Anthon Chekhov wants to tell that everyone has his own personality developments and ways of overcoming them. In the drama, Smirnov has problem with his personality development. It influences his personality in facing the others people. -

Anatomy of the Dog the Present Volume of Anatomy of the Dog Is Based on the 8Th Edition of the Highly Successful German Text-Atlas of Canine Anatomy

Klaus-Dieter Budras · Patrick H. McCarthy · Wolfgang Fricke · Renate Richter Anatomy of the Dog The present volume of Anatomy of the Dog is based on the 8th edition of the highly successful German text-atlas of canine anatomy. Anatomy of the Dog – Fully illustrated with color line diagrams, including unique three-dimensional cross-sectional anatomy, together with radiographs and ultrasound scans – Includes topographic and surface anatomy – Tabular appendices of relational and functional anatomy “A region with which I was very familiar from a surgical standpoint thus became more comprehensible. […] Showing the clinical rele- vance of anatomy in such a way is a powerful tool for stimulating students’ interest. […] In addition to putting anatomical structures into clinical perspective, the text provides a brief but effective guide to dissection.” vet vet The Veterinary Record “The present book-atlas offers the students clear illustrative mate- rial and at the same time an abbreviated textbook for anatomical study and for clinical coordinated study of applied anatomy. Therefore, it provides students with an excellent working know- ledge and understanding of the anatomy of the dog. Beyond this the illustrated text will help in reviewing and in the preparation for examinations. For the practising veterinarians, the book-atlas remains a current quick source of reference for anatomical infor- mation on the dog at the preclinical, diagnostic, clinical and surgical levels.” Acta Veterinaria Hungarica with Aaron Horowitz and Rolf Berg Budras (ed.) Budras ISBN 978-3-89993-018-4 9 783899 9301 84 Fifth, revised edition Klaus-Dieter Budras · Patrick H. McCarthy · Wolfgang Fricke · Renate Richter Anatomy of the Dog The present volume of Anatomy of the Dog is based on the 8th edition of the highly successful German text-atlas of canine anatomy. -

How to Select a Livestock Guardian Dog Puppy

EAN-026 6/20 How to Select a Livestock Guardian Dog Puppy How to Select an LGD Puppy An effective livestock guardian dog (LGD) is the result of properly rearing a puppy with an inherent genetic propensity to protect livestock. Each farm and ranch should strive to source the right kind of genetics for their situation. Keep in mind that LGD behaviors are still greatly influenced by how they are managed during the first year of their life. In contrast, physical traits such as hair coat, color, mature size, etc. are preset by genetics. 1. Buy from reputable genetics that fit your need A knowledgeable breeder will know the pedigree of the pups being offered, as well as their individual personalities and behaviors. Observation over time is generally more reliable than puppy aptitude testing, Bill Costanzo but a few simple tests and observations can be helpful Research Specialist II if you have the hands-on opportunity. Ask to see Livestock Guardian Dog Project Texas A&M AgriLife Research the parents of the litter and to ensure both parents are working LGDs. It is recommended that you Dr. Reid Redden observe the puppies in person before committing to Extension Sheep & Goat Specialist the purchase, yet in some circumstances, this is not Texas A&M AgriLife Extension possible. In this situation, quiz the breeder about traits Interim Center Director listed below and request pictures or video of the pups Texas A&M AgriLife Research if possible. Dr. John Walker Professor & Range Specialist 2. Good health Texas A&M AgriLife Research Healthy pups are a combination of proper genetics and All of the Texas A&M University System management. -

Multnomah Irish Setter Association Independent Specialty with NOHS Sunday, October 11, 2020 Event #2020159405

REVISED Specialty Premium List Multnomah Irish Setter Association Independent Specialty with NOHS Sunday, October 11, 2020 Event #2020159405 NEW SITE Property of Judy Chambers, 10184 Ehlen Rd NE Aurora OR 97003 Outdoors on grass regardless of weather Show hours 8 am to 6 pm NEW Closing Date: Thursday October 1, 2020, 8 pm PDT No entry may be accepted, cancelled, altered, or substituted after the closing date and time except as provided in Chapter 11, Section 6 of the Dog Show Rules. EVENT SECRETARY Judi James dba My Dogs Gym 1265 Summer St NE, Salem, OR 97301 (971) 239-5518 EM: [email protected] Emergency Contact Day of Show Judy C. (503) 705-7099 or Judi J. (971) 239-5518 Change of Judge: Linda Riedel #2775, Pasco Washington will judge all Conformation & Junior Showmanship in lieu of Carla M. Mathis Sweepstakes Judge: Laura Reeves Pre-Order Catalog Official Photographer Please per-order your catalog(s) with your entry by checking the Steven Crumley box and including $5 with your entry fee. There will be a limited email: [email protected] number of catalogs available for sale day of show at $7 each. CERTIFICATION Permission is granted by the American Kennel Club for the holding of this event under American Kennel Club rules and regulations. Gina DiNardo, Secretary NOTICE In accordance with Oregon Governor Brown’s Executive Order 20-12 Stay Home, Save Lives requiring social distancing measures for public or private gatherings outside the home, a site distance plan requiring at least six feet between individuals must be maintained at all times (See Article 1, section A). -

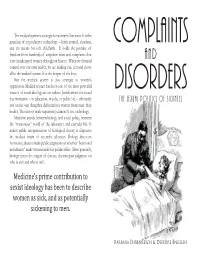

Complaints and Disorders

The medical system is strategic for women’s liberation. It is the guardian of reproductive technology – birth control, abortion, and the means for safe childbirth. It holds the promise of Complaints freedom from hundreds of unspoken fears and complaints that have handicapped women throughout history. When we demand AND control over our own bodies, we are making that demand above all to the medical system. It is the keeper of the keys. But the medical system is also strategic to women’s oppression. Medical science has been one of the most powerful sources of sexist ideology in our culture. Justifi cations for sexual Disorders discrimination – in education, in jobs, in public life – ultimately The Sexual Politics of Sickness rest on the one thing that differentiates women from men: their bodies. Theories of male superiority ultimately rest on biology. Medicine stands between biology and social policy, between the “mysterious” world of the laboratory and everyday life. It makes public interpretations of biological theory; it dispenses the medical fruits of scientifi c advances. Biology discovers hormones; doctors make public judgments on whether “hormonal unbalances” make women unfi t for public offi ce. More generally, biology traces the origins of disease; doctors pass judgment on who is sick and who is well. Medicine’s prime contribution to sexist ideology has been to describe women as sick, and as potentially sickening to men. Barbara Ehrenreich & Deirdre English Tacoma, WA This pamphlet was originally copyrighted in 1973. However, the distributors of this zine feel that important [email protected] information such as this should be shared freely.