Tosca | Grove Music Grove Music Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orfeo Ed Euridice

OTELLO (G. Verdi) al Gran Teatre del Liceu Estrena absoluta: Teatro alla Scala de Milà, 5 de febrer de 1887. Estrena a Barcelona i al Gran Teatre del Liceu: 19 de novembre de 1890 Última representació abans de les d’aquesta temporada: 7 de febrer de 2016 Total de representacions al Liceu: 155 TEMPORADA 1890-1891 Nombre de representacions: 9 Dates: 19, 21, 23, 26, 30 novembre; 2, 4, 7, 8 desembre 1890 Núm. històric: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. Otello: Francesco Cardinali Jago: Eugeni Laban Cassio: Alfredo Zonghi Roderigo: Antoni Oliver Lodovico: Luis Visconti Montano: Josep Boldú Desdemona: Mila Kupfer-Berger Emilia: Tilde Carotini Director: Edoardo Mascheroni Director d’escena: Sr. Ferrer TEMPORADA DE PRIMAVERA DE 1891 Nombre de representacions: 8 Dates: 25, 26 abril; 5, 7, 10, 13, 16, 18 maig 1891 Núm. històric: 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17. Última representació: 8 desembre 1890 Otello: Francesco Cardinali Jago: Eugeni Laban Cassio: Alfredo Zonghi Roderigo: Antoni Oliver Lodovico: Luis Visconti Montano: Costantino Thos Desdemona: Kate Bensberg (abril) Eva Tetrazzini (maig) Emilia: Tilde Carotini Director: Edoardo Mascheroni 1 TEMPORADA DE PRIMAVERA DE 1892 Nombre de representacions: 5 Dates: 17, 18, 24, 26, 28 abril 1892 Núm. històric: 18, 19, 20, 21, 22. Última representació: 18 maig 1891 Otello: Francesco Tamagno Jago: Ramon Blanchart Cassio: Roberto Ramini Roderigo: Antoni Oliver Lodovico: Giuseppe De Grazia Montano: Costantino Thos Un araldo: Domènec Campins Desdemona: Eva Tetrazzini Emilia: Giuseppina Zeppilli-Villani Director: Cleofonte Campanini TEMPORADA 1892-1893 Nombre de representacions: 12 Dates: 22, 23, 25, 26, 30 desembre 1892 / 1, 14, 15, 25, 31 gener; 5, 6, febrer 1892 Núm. -

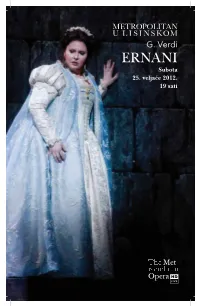

ERNANI Web.Pdf

Foto: Metropolitan opera G. Verdi ERNANI Subota, 25. veljae 2012., 19 sati THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM ITS FOUNDING SPONZOR Neubauer Family Foundation GLOBAL CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP OF THE MET LIVE IN HD IS PROVIDED BY THE HD BRODCASTS ARE SUPPORTED BY Giuseppe Verdi ERNANI Opera u etiri ina Libreto: Francesco Maria Piave prema drami Hernani Victora Hugoa SUBOTA, 25. VELJAČE 2012. POČETAK U 19 SATI. Praizvedba: Teatro La Fenice u Veneciji, 9. ožujka 1844. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Narodno zemaljsko kazalište, Zagreb, 18. studenoga 1871. Prva izvedba u Metropolitanu: 28. siječnja 1903. Premijera ove izvedbe: 18. studenoga 1983. ERNANI Marcello Giordani JAGO Jeremy Galyon DON CARLO, BUDUĆI CARLO V. Zbor i orkestar Metropolitana Dmitrij Hvorostovsky ZBOROVOĐA Donald Palumbo DON RUY GOMEZ DE SILVA DIRIGENT Marco Armiliato Ferruccio Furlanetto REDATELJ I SCENOGRAF ELVIRA Angela Meade Pier Luigi Samaritani GIOVANNA Mary Ann McCormick KOSTIMOGRAF Peter J. Hall DON RICCARDO OBLIKOVATELJ RASVJETE Gil Wechsler Adam Laurence Herskowitz SCENSKA POSTAVA Peter McClintock Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: Radnja se događa u Španjolskoj 1519. godine. Stanka nakon prvoga i drugoga čina. Svršetak oko 22 sata i 50 minuta. Tekst: talijanski. Titlovi: engleski. Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: PRVI IN - IL BANDITO (“Mercè, diletti amici… Come rugiada al ODMETNIK cespite… Oh tu che l’ alma adora”). Otac Don Carlosa, u operi Don Carla, Druga slika dogaa se u Elvirinim odajama u budueg Carla V., Filip Lijepi, dao je Silvinu dvorcu. Užasnuta moguim brakom smaknuti vojvodu od Segovije, oduzevši sa Silvom, Elvira eka voljenog Ernanija da mu imovinu i prognavši obitelj. -

Corso Di Dottorato Di Ricerca in Storia Delle Arti Tesi Di Ricerca

Corso di Dottorato di ricerca in Storia delle Arti ciclo XXI Tesi di Ricerca «THE PHENOMENAL CONTRALTO» Vita e carriera artistica di Eugenia Mantelli SSD: L-ART/07 Musicologia e storia della musica Coordinatore del Dottorato ch. prof. Piermario Vescovo Supervisore ch. prof. Paolo Pinamonti Dottorando Federica Camata Matricola 808540 «THE PHENOMENAL CONTRALTO». VITA E CARRIERA ARTISTICA DI EUGENIA MANTELLI INDICE Introduzione p. 3 1. Biografia di Eugenia Mantelli p. 7 1.1. L’infanzia e gli studi p. 9 1.2. Il debutto al Teatro de São Carlos p. 13 1.3. La carriera internazionale p. 16 1.3.1. 1886: prima tournée in Sudamerica p. 17 1.3.2. 1887: seconda tournée in Sudamerica p. 24 1.3.3. 1889: terza tournée in Sudamerica p. 26 1.3.4. Eugenia Mantelli-Mantovani p. 28 1.3.5. Dal Bolshoi al Covent Garden p. 31 1.3.6. ¡Que viva Chile! Ultime tournée in Sudamerica p. 33 1.4. New York, il Metropolitan e le tournée negli Stati Uniti p. 36 1.4.1. Eugenia Mantelli-De Angelis p. 47 1.5. «Madame Mantelli has gone into vaudeville» p. 51 1.6. Mantelli Operatic Company p. 66 1.7. Attività artistica in Italia p. 69 1.8. Le ultime stagioni portoghesi e il ritiro dalle scene p. 81 1.9. Gli anni d’insegnamento p. 91 1.10.Requiem per Eugenia p. 99 1 2. Cronologia delle rappresentazioni p. 104 2.1. Nota alla consultazione p. 105 2.2. Tabella cronologica p. 107 3. Le fonti sonore p. 195 3.1. -

05-09-2019 Siegfried Eve.Indd

Synopsis Act I Mythical times. In his cave in the forest, the dwarf Mime forges a sword for his foster son Siegfried. He hates Siegfried but hopes that the youth will kill the dragon Fafner, who guards the Nibelungs’ treasure, so that Mime can take the all-powerful ring from him. Siegfried arrives and smashes the new sword, raging at Mime’s incompetence. Having realized that he can’t be the dwarf’s son, as there is no physical resemblance between them, he demands to know who his parents were. For the first time, Mime tells Siegfried how he found his mother, Sieglinde, in the woods, who died giving birth to him. When he shows Siegfried the fragments of his father’s sword, Nothung, Siegfried orders Mime to repair it for him and storms out. As Mime sinks down in despair, a stranger enters. It is Wotan, lord of the gods, in human disguise as the Wanderer. He challenges the fearful Mime to a riddle competition, in which the loser forfeits his head. The Wanderer easily answers Mime’s three questions about the Nibelungs, the giants, and the gods. Mime, in turn, knows the answers to the traveler’s first two questions but gives up in terror when asked who will repair the sword Nothung. The Wanderer admonishes Mime for inquiring about faraway matters when he knows nothing about what closely concerns him. Then he departs, leaving the dwarf’s head to “him who knows no fear” and who will re-forge the magic blade. When Siegfried returns demanding his father’s sword, Mime tells him that he can’t repair it. -

Manon Lescaut

CopertaToPrint_lsc:v 18-01-2010 10:57 Pagina 1 1 La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2010 1 2010 Fondazione Stagione 2010 Teatro La Fenice di Venezia Lirica e Balletto Giacomo Puccini Manon escaut L Lescaut anon anon m uccini p iacomo iacomo g FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA CopertaToPrint_lsc:v 18-01-2010 10:57 Pagina 2 foto © Michele Crosera Visite a Teatro Eventi Gestione Bookshop e merchandising Teatro La Fenice Gestione marchio Teatro La Fenice® Caffetteria Pubblicità Sponsorizzazioni Fund raising Per informazioni: Fest srl, Fenice Servizi Teatrali San Marco 4387, 30124 Venezia Tel: +39 041 786672 - Fax: +39 041 786677 [email protected] - www.festfenice.com FONDAZIONE AMICI DELLA FENICE STAGIONE 2010 Incontro con l’opera Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee lunedì 25 gennaio 2010 ore 18.00 LUCA MOSCA Manon Lescaut Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee venerdì 5 febbraio 2010 ore 18.00 PIERO MIOLI Il barbiere di Siviglia Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee mercoledì 10 marzo 2010 ore 18.00 ENZO RESTAGNO Dido and Aeneas Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee venerdì 14 maggio 2010 ore 18.00 LORENZO ARRUGA Don Giovanni Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee lunedì 21 giugno 2010 ore 18.00 GIORGIO PESTELLI The Turn of the Screw Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee mercoledì 22 settembre 2010 ore 18.00 Clavicembalo francese a due manuali copia dello MICHELE DALL’ONGARO strumento di Goermans-Taskin, costruito attorno alla metà del XVIII secolo (originale presso la Russell Rigoletto Collection di Edimburgo). Opera del M° cembalaro Luca Vismara di Seregno Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee (MI); ultimato nel gennaio 1998. -

Syapnony Orcnestrh

BOSTON SYAPnONY ORCnESTRH 1901-1902 ^cc PRoGRSAAE HIGH OPINIONS REGARDING THE PIANOFORTEvS " In my opinion, they rank with the best pianos made." Wm. Mason. " I beheve your pianos to be of the very first rank." Arthur Nikisch. Dr. Wm. riason. Arthur Nikisch. Harold Bauer. "In my opinion, no finer instrument exists than the Mason & HamHn of to-day." Harold Bauer. " It is, I believe, an instru- ment of the very first rank." MORITZ MOSZKOWSKI. " It IS unsurpassed, so far as I know." Emil Paur. Moritz noszkowslci. Emil Paur. NEW ENGLAND REPRESENTATIVES M. STEINERT & SONS COMPANY 162 BOYLSTON STREET Boston Symphony Orchestra* SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON, HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES. Ticket """T'Office, 1492 ' ""!' BACK BAY. TELEPHONE, | TI [ Administration Offices, 1471 TWENTY-FIRST SEASON, I 901 -I 902. WILHELM GERICKE, CONDUCTOR. PROGRAMME OF THE THIRD REHEARSAL and CONCERT WITH HISTORICAL AND DESOUPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE jt jt ^ ji FRIDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER 1, AT 2.30 O'CLOCK. SATURDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 2, AT 8.00 O'CLOCK. PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER. (101) QUARTER G R A N D% THIS instrument, which we have just produced, defines an epoch in the history of piano- forte making and is the only success- ^ ful very small grand ever made. ^ Beautiful quality of tone and delightful touch — taking but little more space than an upright, it sur- passes it in all the qualities desired in a pianoforte. CHICKERING ^ Sons IPianoforte flPafterg 7p/ TREMONT STREET B S T N , U . S . A . (102) TWENTY-FIRST SEASON, 1901-1902. Third Rehearsal and Concert* FRIDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER i, ait 2.30 o'clock. -

CHAN 3000 FRONT.Qxd

CHAN 3000 FRONT.qxd 22/8/07 1:07 pm Page 1 CHAN 3000(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH David Parry PETE MOOES FOUNDATION Puccini TOSCA CHAN 3000(2) BOOK.qxd 22/8/07 1:14 pm Page 2 Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) Tosca AKG An opera in three acts Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica after the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou English version by Edmund Tracey Floria Tosca, celebrated opera singer ..............................................................Jane Eaglen soprano Mario Cavaradossi, painter ..........................................................................Dennis O’Neill tenor Baron Scarpia, Chief of Police................................................................Gregory Yurisich baritone Cesare Angelotti, resistance fighter ........................................................................Peter Rose bass Sacristan ....................................................................................................Andrew Shore baritone Spoletta, police agent ........................................................................................John Daszak tenor Sciarrone, Baron Scarpia’s orderly ..............................................Christopher Booth-Jones baritone Jailor ........................................................................................................Ashley Holland baritone A Shepherd Boy ............................................................................................Charbel Michael alto Geoffrey Mitchell Choir The Peter Kay Children’s Choir Giacomo Puccini, c. 1900 -

Stony Brook Opera 2015-2016 Season

LONG ISLAND OPERA GUILD NEWSLETTER MARCH 2016 Stony Brook Opera 2015-2016 Season A letter from the Artistic Director of Stony Brook Opera Our current season will end with a semi-staged concert performance of Giacomo Puccini’s beloved masterpiece La Department and friends from New York City who attended Bohème, sung in the original Italian language with projected those performances all told me that from a theatrical point of titles in English. The Stony Brook Symphony will be on stage, view nothing was lacking, and that they enjoyed immensely with the opera chorus behind it on risers. The Stony Brook being able to see how the singers, chorus, and orchestra Opera cast will perform from memory on the stage space in interact in the overall musical and dramatic experience. That is front of the orchestra. Timothy Long will conduct the cast, not possible when the orchestra is out of sight, as it always is chorus and orchestra. Brenda Harris, Performing Artist in in a full production. From a theatrical point of view, La Residence and a leading soprano in American regional opera Bohème presents a far greater challenge than Lucia did, in part will direct the singers, who will be fully blocked, and will use because it calls for so many “things” on stage throughout the props and furniture and minimal costuming as appropriate. opera—not only essential furniture pieces, but also numerous Tomas Del Valle of the Theatre Arts Department makes his small hand props, all of which are vital to the narrative, and Stony Brook Opera debut as the lighting designer, and he is carry great emotional weight in the plot, such as the candle planning exciting theatrical lighting for the space where the and the key, and Mimì’s bonnet, to name a few. -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected]

Nineteenth-Century Music Review, 14 (2017), pp 211–242. © Cambridge University Press, 2016 doi:10.1017/S1479409816000082 First published online 8 September 2016 Romantic Nostalgia and Wagnerismo During the Age of Verismo: The Case of Alberto Franchetti* Davide Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected] The world premiere of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana on 17 May 1890 immediately became a central event in Italy’s recent operatic history. As contemporary music critic and composer, Francesco D’Arcais, wrote: Maybe for the first time, at least in quite a while, learned people, the audience and the press shared the same opinion on an opera. [Composers] called upon to choose the works to be staged, among those presented for the Sonzogno [opera] competition, immediately picked Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana as one of the best; the audience awarded this composer triumphal honours, and the press 1 unanimously praised it to the heavens. D’Arcais acknowledged Mascagni’smeritsbut,inthesamearticle,alsourgedcaution in too enthusiastically festooning the work with critical laurels: the dangers of excessive adulation had already become alarmingly apparent in numerous ill-starred precedents. In the two decades prior to its premiere, several other Italian composers similarly attained outstanding critical and popular success with a single work, but were later unable to emulate their earlier achievements. Among these composers were Filippo Marchetti (Ruy Blas, 1869), Stefano Gobatti (IGoti, 1873), Arrigo Boito (with the revised version of Mefistofele, 1875), Amilcare Ponchielli (La Gioconda, 1876) and Giovanni Bottesini (Ero e Leandro, 1879). Once again, and more than a decade after Bottesini’s one-hit wonder, D’Arcais found himself wondering whether in Mascagni ‘We [Italians] have finally [found] … the legitimate successor to [our] great composers, the person 2 who will perpetuate our musical glory?’ This hoary nationalist interrogative returned in 1890 like an old-fashioned curse. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 35,1915

PARSONS THEATRE HARTFORD Thirty-fifth Season. 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK. Conductor WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE MONDAY EVENING, MARCH 27 AT 8.15 COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY C. A.-ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER €i Yes, It's a Steinway" ISN'T there supreme satisfaction in being able to say that of the piano in your home? Would you have the same feeling about any other piano? " It's a Steinway." Nothing more need be said. Everybody knows you have chosen wisely; you have given to your home the very best that money can buy. You will never even think of changing this piano for any other. As the years go by the words "It's a Steinway" will mean more and more to you, and thousands of times, as you continue to enjoy through life the com- panionship of that noble instrument, absolutely without a peer, you will say to yourself: "How glad I am I paid the few extra dollars and got a Steinway." STEINWAY HALL 107-109 East 14th Street, New York Subway Express Station at the Door Represented by the Foremost Dealers Everywhere Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor PERSONNEL Violins. Witek, A. Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Rissland, K. Concert-master. Koessler, M. Schmidt, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Bak, A. Traupe, W. Goldstein, H. Tak, E. Ribarsch, A. Baraniecki, A. Sauvlet. H. Habenicht, W. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Goldstein, S. Fiumara, P. Spoor, S. Siilzen, H. Fiedler, A. Griinberg, M. Pinfield, C. Gerardi, A. Kurth, R. -

Milka Trnina

Èitajte o glazbi i svim Èitajte o glazbi i svim nje-zinim pojavno- njezinim pojavnostima webzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuzici] stima iz pera naših ponajboljih pisaca iz pera naših ponajbo-? Èitajte o glazbi i svim u esejima i èlancima koje možete èitati ljih pisaca u esejima njezinim pojavnostima webzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuzici] na stranicama našeg èasopisa WAM. ? i èlancima koje možete iz pera naših ponajbo- Èitajte o glazbi i svim èitati na stranicama ljih pisaca u esejima njezinim pojavnostima našeg èasopisa WAM. i èlancima koje možete iz pera naših ponaj- èitati na stranicama boljih pisaca u esejima našeg èasopisa WAM. eseji i èlancima koje možete èitati na stranicama našeg èasopisa WAM. 1 Ilustracija Munir Vejzoviæ Marija Barbieri MILKA TRNINA - GREAT TOSCA Èitajte o glazbi i svim Čitajte o glazbi i svim njezinim pojavnostima njezinim pojavnostima iz pera naših ponaj- iz pera naših ponaj- Èitajte o glazbi i svim boljih pisaca u esejima boljih pisaca u esejima njezinim pojavnostima i èlancima koje možete i člancima koje možete iz pera naših ponaj-Èitajte o glazbi i svim èitati na stranicama čitati na stranicama boljih pisaca u esejimanjezinim pojavnostima našeg èasopisa WAM. našeg časopisa WAM. ? webzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzii èlancimanoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzinoaudijuimuziciwebzino koje možeteiz pera naših ponaj-