National Performing Tradition As a Basis of Opera Creative Work of G. Verdi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

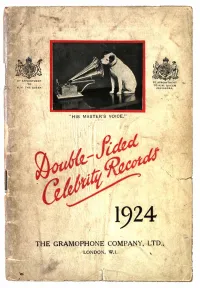

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

17.2. Cylinders, Ed. Discs, Pathes. 7-26

CYLINDERS 2M WA = 2-minute wax, 4M WA= 4-minute wax, 4M BA = Edison Blue Amberol, OBT = original box and top, OP = original descriptive pamphlet. Repro B/T = Excellent reproduction Edison orange box and printed top. All others in clean, used boxes. Any mold on wax cylinders is always described. All cylinders not described as in OB (original box with generic top) or OBT (original box and original top) are boxed (most in good quality boxes) with tops and are standard 2¼” diameter. All grading is visual and refers to the cylinders rather than the boxes. Any major box problems are noted. CARLO ALBANI [t] 1039. Edison BA 28116. LA GIOCONDA: Cielo e mar (Ponchielli). Repro B/T. Just about 1-2. $30.00. MARIO ANCONA [b] 1001. Edison 2M Wax B-41. LES HUGUENOTS: Nobil dama (Meyerbeer). Announced by Ancona. OBT. Just about 1-2. $75.00. BLANCHE ARRAL [s] 1007. Edison Wax 4-M Amberol 35005. LE COEUR ET LA MAIN: Boléro (Lecocq). This and the following two cylinders are particularly spirited performances. OBT. Slight box wear. Just about 1-2. $50.00. 1014. Edison Wax 4-M Amberol 35006. LA VÉRITABLE MANOLA [Boléro Espagnole] (Bourgeois). OBT. Just about 1-2. $50.00. 1009. Edison Wax 4-M Amberol 35019. GIROLFÉ-GIROFLA: Brindisi (Lecocq). OBT. Just about 1-2. $50.00. PAUL AUMONIER [bs] 1013. Pathé Wax 2-M 1111. LES SAPINS (Dupont). OB. 2. $20.00. MARIA AVEZZA [s]. See FRANCESCO DADDI [t] ALESSANDRO BONCI [t] 1037. Edison BA 29004. LUCIA: Fra poco a me ricovero (Donizetti). -

Verdi's Rigoletto

Verdi’s Rigoletto - A discographical conspectus by Ralph Moore It is hard if not impossible, to make a representative survey of recordings of Rigoletto, given that there are 200 in the catalogue; I can only compromise by compiling a somewhat arbitrary list comprising of a selection of the best-known and those which appeal to me. For a start, there are thirty or so studio recordings in Italian; I begin with one made in 1927 and 1930, as those made earlier than that are really only for the specialist. I then consider eighteen of the studio versions made since that one. I have not reviewed minor recordings or those which in my estimation do not reach the requisite standard; I freely admit that I cannot countenance those by Sinopoli in 1984, Chailly in 1988, Rahbari in 1991 or Rizzi in 1993 for a combination of reasons, including an aversion to certain singers – for example Gruberova’s shrill squeak of a soprano and what I hear as the bleat in Bruson’s baritone and the forced wobble in Nucci’s – and the existence of a better, earlier version by the same artists (as with the Rudel recording with Milnes, Kraus and Sills caught too late) or lacklustre singing in general from artists of insufficient calibre (Rahbari and Rizzi). Nor can I endorse Dmitri Hvorostovsky’s final recording; whether it was as a result of his sad, terminal illness or the vocal decline which had already set in I cannot say, but it does the memory of him in his prime no favours and he is in any case indifferently partnered. -

Homage to Two Glories of Italian Music: Arturo Toscanini and Magda Olivero

HOMAGE TO TWO GLORIES OF ITALIAN MUSIC: ARTURO TOSCANINI AND MAGDA OLIVERO Emilio Spedicato University of Bergamo December 2007 [email protected] Dedicated to: Giuseppe Valdengo, baritone chosen by Toscanini, who returned to the Maestro October 2007 This paper produced for the magazine Liberal, here given with marginal changes. My thanks to Countess Emanuela Castelbarco, granddaughter of Toscanini, for checking the part about her grandfather and for suggestions, and to Signora della Lirica, Magda Olivero Busch, for checking the part relevant to her. 1 RECALLING TOSCANINI, ITALIAN GLORY IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY As I have previously stated in my article on Andrea Luchesi and Mozart (the new book by Taboga on Mozart death is due soon, containing material discovered in the last ten years) I am no musicologist, just a person interested in classical music and, in more recent years, in opera and folk music. I have had the chance of meeting personally great people in music, such as the pianist Badura-Skoda, and opera stars such as Taddei, Valdengo, Di Stefano (or should I say his wife Monika, since Pippo has not yet recovered from a violent attack by robbers in Kenya; they hit him on the head when he tried to protect the medal Toscanini had given him; though no more in a coma, he is still paralyzed), Bergonzi, Prandelli, Anita Cerquetti and especially Magda Olivero. A I have read numerous books about these figures, eight about Toscanini alone, and I was also able to communicate with Harvey Sachs, widely considered the main biographer of Toscanini, telling him why Toscanini broke with Alberto Erede and informing him that, contrary to what he stated in his book on Toscanini’s letters, there exists one letter by one of his lovers, Rosina Storchio. -

“Riccione Il Mio Ritrovo Estivo Preferito”. Il Divino Tenore Giuseppe Borgatti

Bicentenario della nascita di Verdi e Wagner FOSCO ROCCHETTA “RICCIONE IL MIO RITROVO ESTIVO PREFERITO” IL DIVINO TENORE GIUSEPPE BORGATTI NELLA RICCIONE DELLA BELLE ÉPOQUE la Piazza Editrice 2013 In copertina: rielaborazione di Marco Pasini di una foto che ritrae Giuseppe Borgatti sulla spiaggia di Riccione nell’estate 1899, tratta dalla rivista “Cronaca dei teatri” Bologna 1899. Copertina in stile Liberty di Davide Polverelli. In 3a di copertina curriculum dell’autore, in 4a, collage di cartoline di Riccione degli inizi del Novecento delle raccolte di Anna Marabini e Gherardo Bagli. Ringraziamenti Antonella Imolesi Pozzi - Responsabile del Fondo Piancastelli della Biblioteca “A. Saffi” di Forlì, Ambra Raggi, Graziella Galeotti, Maura Parrinello del medesimo Istituto; Gessica Boni del Servizio fotografico della Biblioteca Malatestiana di Cesena; Gloria Gruppioni della Cassa di Risparmio di Cento (FE); Kristina Unger della Biblioteca del Wagner Museum, Bayreuth (Germania); Paola Delbianco, Maria Cecilia Antoni, Cesare Banducci, Gilberto Filanti, Augusto Giannotti ed Anna Morri della Biblioteca Gambalunga di Rimini; Anna Marabini e Gherardo Bagli di Riccione per l’autorizzazione alla scansione di cartoline di loro proprietà; Astro Bologna, Maria Magari, Andrea Corazza, Fulvio Bugli, Daniele Magnani di Riccione; Christina Gruber di Miramare di Rimini; Roberto De Grandis per il disegno di Giuseppe Borgatti in accappatoio. Per la cortese ospitalità. Si ringraziano anche: Cura grafica: Luigi Vendramin. A mia moglie IRINA collaboratrice preziosa e paziente di questo e di altri miei libri “Incominciai ad imparare a fare il fabbro, per comporre una spada del baldanzoso eroe [Sigfrido] e ricordo che lavorai due mesi con l'incudine e il martello e col mantice. -

Italialaiset Wagner-Muusikot Teksti: Robert Storm

Italialaiset Wagner-muusikot Teksti: Robert Storm “Keskinkertainen vaikutelma. Musiikki tettiin Wagnerin musiikin italialaistamises- kaunista silloin, kun se on selkeää ja siinä ta. Lisäksi Borgatti lauloi aina Wagner-roo- on ajatusta. Toiminta ja teksti hitaita. Täs- lit italiaksi. tä seurauksena tylsistyminen. Kauniita soiti- Wagnerin teokset esitettiin pitkään Ita- nefektejä. Liikaa pidätyksiä, mikä tekee mu- liassa ja monissa muissakin maissa italian siikista raskasta. Keskinkertainen esitys. Pal- kielellä. Erityisesti Lohengrin tuntui sopi- jon intoa, mutta ei runollisuutta tai hienos- van italialaisille laulajille. Sen nimiosaa ovat tuneisuutta. Vaikeat kohdat aina surkeita.” esittäneet mm. Enrico Caruso ja Beniami- Esittäjien kannalta on todettava, että ky- no Gigli. Italiankielisiä Wagner-esityksiä on seinen esitys onnistui poikkeuksellisen huo- julkaistu levylläkin useita: Hermann Scher- nosti. Esiintyjät olivat kuulleet Verdin olevan chenin johtama Rienzi (pääosissa Giuseppe yleisön joukossa ja olivat tämän takia her- di Stefano ja Raina Kabaivanska), Frances- mostuneita. Toisen näytöksen jälkeen kuu- co Molinari-Pradellin Lentävä hollantilainen lui yleisöstä huuto: “Viva il Maestro Verdi!” (Aldo Protti ja Dorothy Dow), Karl Böhmin Verdille taputettiin vartin ajan, mutta hän Tannhäuser (Renata Tebaldi, Boris Chris- ei halunnut nousta esiin. toff ja saksaksi laulava Hans Beirer), Gab- Lohengrinin ansiosta Wagnerista tehtiin riele Santinin Lohengrin (Gino Penno, Re- Bolognan kunniakansalainen. Teatro Co- nata Tebaldi ja Giangiacomo Guelfi), Lov- munale di Bologna kunnostautui myöhem- ro von Matacicin Mestarilaulajat (Giusep- minkin Wagner-teatterina, jossa useat Wag- pe Taddei, Boris Christoff ja Luigi Infan- nerin teokset saivat Italian ensi-iltansa: 1872 tino) ja Vittorio Guin Parsifal (Africo Bal- Tannhäuser, 1876 Rienzi, 1877 Lentävä hollan- delli, Maria Callas, Boris Christoff ja Ro- tilainen ja 1888 Tristan ja Isolde. -

1 CRONOLOGIA LICEISTA S'inclou Una Llista Amb Les Representaciones

CRONOLOGIA LICEISTA S’inclou una llista amb les representaciones de Rigoletto de Verdi en la història del Gran Teatre del Liceu. Estrena absoluta: 11 de març de 1851 al teatre La Fenice de Venècia Estrena a Barcelona i al Liceu: 3 de desembre de 1853 Última representació: 5 de gener del 2005 Total de representacions: 362 TEMPORADA 1853-1854 3-XII-1853 RIGOLETTO Llibret de Francesco Maria Piave. Música de Giuseppe Verdi. Nombre de representacions: 25 Núm. històric: de l’1 al 25. Dates: 3, 4, 8, 11, 15, 22, 23, 25, 26 desembre 1853; 5, 6, 12, 15, 19, 31 gener; 7, 12, 26 febrer; 1, 11, 23 març; 6, 17 abril; 16 maig; 2 juny 1854. Duca di Mantova: Ettore Irfré Rigoletto: Antonio Superchi Gilda: Amalia Corbari Sparafucile: Agustí Rodas Maddalena: Antònia Aguiló-Donatutti Giovanna: Josefa Rodés Conte di Monterone: José Aznar / Luigi Venturi (17 abril) Marullo: Josep Obiols Borsa: Luigi Devezzi Conte di Ceprano: Francesc Sánchez Contessa di Ceprano: Cristina Arrau Usciere: Francesc Nicola Paggio: Josefa Garriche Director: Eusebi Dalmau TEMPORADA 1854-1855 Nombre de representacions: 8 Número històric al Liceu: 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 Dates: 7, 10, 18 febrer; 13 març; 17 abril; 17, 27 maig; 7 juny 1855. Nota: Felice Varesi havia estat el primer Rigoletto a l'estrena mundial a la Fenice de Venècia l'11 de març de 1851. Duca di Mantova: Giacomo Galvani Rigoletto: Felice Varesi Gilda: Virginia Tilli Sparafucile: Agustí Rodas Maddalena: Matilde Cavalletti / Antònia Aguiló-Donatutti (7 de juny) Giovanna: Sra. Sotillo Conte di Monterone: Achille Rossi 1 Marullo: Josep Obiols Borsa: Josep Grau Contessa di Ceprano: Antònia Aguiló-Donatutti Director: Gabriel Balart TEMPORADA 1855-1856 L'òpera és anunciada com "Il Rigoletto". -

Where Have All the Great Voices Gone?

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 16, Number 33, August 18, 1989 namely, His role as the Creator-is something entirely dif ferent than a mere cry for help in time of need. The mere repetition of the seventh line already makes it clear that the subject here is this other quality of emotion, since the only sense in repeating it, would be to express something other than what has come before. And that is precisely what is made explicit by the shift in register. Within this final word of the song, "beten," lies all the devotion of which man is capable, his humility before God a humility, however, in which he experiences at the same Where have all the time his greatest sense of elevation, because in his perfect concentration upon God, he comes to most resemble Him. great voices gone? When in this way, a person is immersed in perfect devotion to God, that person is consummating his capax Dei, his by Gino Bechi participation in God.If instead, this final word "beten" were sung without any clear register shift, as is oftenthe case when the singer does not use the belcanto method, then this deep Mr. Bechi, one o/the great Italian baritones o/the interwar meaning is, at the very least, only superficially rendered. era, offered the /ollowing comlnents to the conference "Giu It is no accident, that modem composers have such a seppe Verdi and the Scientific Tuning Fork," held on June difficult time creating works which can even approximate the 20, 1989 at the Cini Foundation in Venice, Italy. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE VOCAL TECHNIQUE OF THE VERDI BARITONE JOHN CURRAN CARPENTER SPRING 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Music with honors in Music Reviewed and approved* by the following: Charles Youmans Associate Professor of Musicology Thesis Supervisor Mark Ballora Associate Professor of Music Technology Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT I wrote this thesis in an attempt to provide useful information about the vocal technique of great operatic singers, especially “Verdi baritones”—singers specializing in dramatic lead roles of this voice-type in Giuseppe Verdi’s operas. Through careful scrutiny of historical performances by great singers of the past century, I attempt to show that attentive listening can be a vitally important component of a singer’s technical development. This approach is especially valuable within the context of a mentor/apprentice relationship, a centuries-old pedagogical tradition in opera that relies heavily on figurative language to capture the relationship between physical sensation and quality of sound. Using insights gleaned from conversations with my own teacher, the heldentenor Graham Sanders, I analyze selected YouTube clips to demonstrate the relevance of sensitive listening for developing smoothness of tone, maximum resonance, legato, and other related issues. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. -

Archivio Giuseppe De Luca 1892 - 1980

Archivio Giuseppe De Luca 1892 - 1980 Progetto Musicisti italiani nel mondo Tipologia d'intervento riordino Estremi cronologici 2018 Descrizione Gruppo degli archivi di musiciti che hanno avuto importanti esperienze internazionali Soggetto conservatore Istituto Nazionale Tostiano - Ortona Condizione giuridica privato Macrotipologia ente di cultura, ricreativo, sportivo, turistico Cenni storico istituzionali L'Istituto Nazionale Tostiano costituito ad Ortona (CH) nel 1983 con Deliberazione del Consiglio Comunale di Ortona n. 161 del 21/03/1983; n. 198 del 27/04/83; n.225 25/07/83 e n. 159 del 14/11/1996, tutte esecutive, è una istituzione di impegno musicologico unica nella regione Abruzzo occupandosi statutariamente della vita e delle opere del compositore Francesco Paolo Tosti, degli altri musicisti abruzzesi e più in generale della musica vocale da camera ed altri settori della cultura musicale. Tale lavoro viene svolto attraverso il collegamento con istituzioni di cultura, editoria ed organizzazione musicale di rilevanza internazionale con un’intensa attività editoriale e discografica, l’attivazione di corsi di perfezionamento internazionali e l’organizzazione di mostre, seminari e convegni in Italia e all’estero. L'Istituto collabora per lo svolgimento delle proprie attività statutarie con diversi enti nazionali ed internazionali in particolare allo sviluppo di progetti di messa in rete di basi di dati e di banche dati. L'Isituto Nazionale Tostiano ha ottenuto il riconoscimento di Istituto culturale di rilevanza nazionale ai sensi -

Enrico Caruso: La Biografia Di Un Divo Alle Origini Dell'industria Culturale

Corso di Laurea specialistica (ordinamento ex D.M. 509/1999) in Musicologia e Beni Musicali Tesi di Laurea Enrico Caruso: la biografia di un divo alle origini dell’industria culturale. Relatore Ch. Prof. Paolo Pinamonti Laureanda Alessandra Bergagnini Matricola 805082 Correlatori Ch. Prof.ssa Adriana Guarnieri Ch. Prof. Carmelo Alberti Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 0 INDICE INTRODUZIONE……………………………………………………………2 1. L’infanzia e l’inizio degli studi….……………………………..……..5 2. Prime esibizioni del giovane Caruso……………………………...10 3. Incontro con Nicola Daspuro e debutto…………………..………13 4. A Livorno incontro con Ada e Giacomo Puccini……...……........19 5. Caruso a Milano………………………………………………….....26 6. Delusione al San Carlo………...……………………........…….….39 7. Breve storia della registrazione e prima incisione di Caruso…..46 8. Caruso emigrante negli Stati Uniti…………………………..…….60 9. Anno 1906, gli avvenimenti infelici………………………..………73 10. Il tradimento di Ada………………………………..…………….….82 11. La popolarità della canzone napoletana oltreoceano…………..89 12. Susseguirsi di stagioni al Metropolitan…………………………...95 13. La guerra oltreoceano…………………………………………….101 14. Caruso e il cinema muto…………………………………….……111 15. L’incontro con Dorothy………………………………………..…..118 16. Malattia e fine del suo canto……………………………………..128 DISCOGRAFIA…………………………………………………….…….141 LISTA DELLE RAPPRESENTAZIONI OPERISTICHE DAL 1895 AL 1921…………………………………………….………...167 CONCLUSIONI……………………………………….………………….192 BIBLIOGRAFIA……………………………………….………………….196 1 INTRODUZIONE Enrico Caruso è il tema della presente tesi, la quale -

Tosca Alla Scala

Mundoclasico.com martes, 18 de febrero de 2020 ITALIA Un clásico de la lírica: Tosca alla Scala FERNANDO PEREGRÍN GUTIÉRREZ Una de las óperas con mayor importancia en la historia del Hernandez como Teatro alla Scala es sin duda Tosca. Desde su estreno en Tosca este teatro, el 17 de marzo de 1900 hasta junio de 2015, © 2020 by Brescia se ha programado en 30 temporadas, con un total de 234 e Amisano funciones. Los más grandes intérpretes -excepción hecha Milán, jueves, 2 de enero de de Maria Callas- de Tosca, Cavaradosi y Scarpia han 2020. Teatro alla subido al escenario de la Sala Piermarini. Al frente de la Scala. Tosca de Giacomo orquesta, han estado los mejores maestros especialistas Puccini. Davide Livermore, director de puccinianos. También la escena ha corrido a cargo de los escena. Gio Forma, escenógrafo. Gianluca más reconocidos registas y escenógrafos. Como ejemplos Falaschi, vestuario. Saioa Hernández (Tosca), Francesco Meli (Cavaradossi), más señalados podemos citar a las sopranos Hariclea Luca Salsi (Barón Scarpia), Alfonso Darclée -la que primera Tosca de la historia-, Claudia Antoniozzi (Sacristán), Carlo Cigni (Cesare Angelotti), Carlo Bosi (Spoletta), Giulio Muzio -la Callas avant la lettre-, Maria Caniglia, Zinka Mastrototaro (Sciarrone), Ernesto Milanova, Renata Tebaldi -la que más veces ha cantado Panariello (Carcelero) y Gianluigi Sartori ese papel en La Scala-, Raina Kabaivanska, Eva Marton y (pastor). Coro di Voci Bianche dell’Accademia Teatro alla Scala. Coro y Grace Bumbry como Tosca; Giuseppe Borgatti, Aureliano Orquesta del Teatro alla Scala. Riccardo Pertile, Beniamino Gigli, Ferrucio Tagliavini, Giuseppe Di Chailly, director Stefano, Plácido Domingo y Luciano Pavarotti, como Cavaradosi; Pascuale Amato, Mariano Stabile, Carlo Galeffi, Giuseppe Taddei, Tito Gobbi, Ettore Bastianini, Piero Cappuccilli, Ruggero Raimondi, Bryn Terfel y Carlo Guelfi como Barone Scarpia.