Ucrs Newsletter - 1961 ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Term Care for Seniors at 640 Lansdowne Avenue

EX3.6 REPORT FOR ACTION Creating New Affordable Rental Homes and Long- Term Care For Seniors at 640 Lansdowne Avenue Date: March 12, 2019 To: Executive Committee From: Deputy City Manager, Community and Social Services & Deputy City Manager, Corporate Services Wards: Ward 9 - Davenport SUMMARY The number of people in Toronto aged 65 and over is expected to almost double by 2041. This growing population of seniors will spur a demand for more affordable housing as well as long-term care homes to be developed specifically to address the evolving needs of seniors in our city. In recognition of the growing urgency to provide both affordable rental and long-term care homes for seniors, at its meeting on May 22, 23 and 24, 2018, City Council requested the Director, Affordable Housing Office, in consultation with CreateTO, to include the opportunity for development of long-term care beds within the affordable housing development planned for a portion of the Toronto Transit Commission property at 640 Lansdowne Avenue. On August 2, 2018, CreateTO, on behalf of the Affordable Housing Office, issued a Request for Proposals ("RFP") for Developing and Operating Affordable Housing Services at 640 Lansdowne Avenue. The RFP offered the one-third, Mixed Use designated portion of the site under a lease arrangement for 99 years at nominal rent to stimulate development of the site and ensure long-term affordability for seniors. The RFP closed on September 6, 2018 and four submissions were received. Since September 2018, CreateTO and City staff have been in discussions with Magellan Community Charities, the proposed proponent, and this report recommends that the City enter into a Letter of Intent ("LOI"), outlining the terms and conditions of the lease and the City's Open Door incentives being provided for the up to 65 affordable rental homes being proposed. -

November 2013 News Col.Pub

WCRA NEWS NOVEMBER 2013 THE POLAR EXPRESS IS COMING! NOV. 30 / DEC. 1 AND DEC. 7 / 8 TICKETS NOW ON SALE RIDING SOME UNIQUE RAILS - CAPE FLYER AND DOWNEASTER WWCRACRA News, Page 2 GENERAL MEETING The General Meeting of the WCRA will be held on October 29, 2013 at 1930 hours at Rainbow Creek Station. Entertainment will be video by Craig McDowall. ON THE COVER On the opposite coast, a unique gathering of railroad faces at Hyannis, MA on the rails of the Cape Cod Central Railroad sees Cape Cod Central 1950’s cab unit and consist intermingling with a new MP36PH-3C of Boston’s MBTA Commuter Rail which has brought the summer weekends only Cape Flyer down from Boston. Read the story starting on page 22. NOVEMBER CALENDAR • West Coast Railway Heritage Park open daily 1000 through 1600k • October 24 through October 29—Mystery of the Magic Pumpkin train ride and Halloween children’s event. Train departures at 10:30 and 1:00PM each day. See page 9. • Friday, November 8 —Deadline for items for the December 2013 WCRA News. • Tuesday, November —Collection Committee meets, 1900 hours, Hastings office • Tuesday, November 26—WCRA Annual Dinner and General Meeting, details to be confirmed • Saturday, November 30 / Sunday, December 1—Polar Express event—trains depart at 1000, 1200, 1400 and 1600 each day. See page 10 and back cover for info, tickets at www.wcra.org The West Coast Railway Association is an historical group dedicated to the preservation of British Columbia railway history. Membership is open to all people with an interest in railways past and present. -

Historical Outlines of Railways in Southwestern Ontario

UCRS Newsletter • July 1990 Toronto & Guelph Railway Note: The Toronto & Goderich Railway Company was estab- At the time of publication of this summary, Pat lished in 1848 to build from Toronto to Guelph, and on Scrimgeour was on the editorial staff of the Upper to Goderich, on Lake Huron. The Toronto & Guelph Canada Railway Society (UCRS) newsletter. This doc- was incorporated in 1851 to succeed the Toronto & ument is a most useful summary of the many pioneer Goderich with powers to build a line only as far as Guelph. lines that criss-crossed south-western Ontario in the th th The Toronto & Guelph was amalgamated with five 19 and early 20 centuries. other railway companies in 1854 to form the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada. The GTR opened the T&G line in 1856. 32 - Historical Outlines of Railways Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada in Southwestern Ontario The Grand Trunk was incorporated in 1852 with au- BY PAT SCRIMGEOUR thority to build a line from Montreal to Toronto, assum- ing the rights of the Montreal & Kingston Railway Company and the Kingston & Toronto Railway Com- The following items are brief histories of the railway pany, and with authority to unite small railway compa- companies in the area between Toronto and London. nies to build a main trunk line. To this end, the follow- Only the railways built in or connecting into the area ing companies were amalgamated with the GTR in are shown on the map below, and connecting lines in 1853 and 1854: the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Toronto, Hamilton; and London are not included. -

Rapid Transit in Toronto Levyrapidtransit.Ca TABLE of CONTENTS

The Neptis Foundation has collaborated with Edward J. Levy to publish this history of rapid transit proposals for the City of Toronto. Given Neptis’s focus on regional issues, we have supported Levy’s work because it demon- strates clearly that regional rapid transit cannot function eff ectively without a well-designed network at the core of the region. Toronto does not yet have such a network, as you will discover through the maps and historical photographs in this interactive web-book. We hope the material will contribute to ongoing debates on the need to create such a network. This web-book would not been produced without the vital eff orts of Philippa Campsie and Brent Gilliard, who have worked with Mr. Levy over two years to organize, edit, and present the volumes of text and illustrations. 1 Rapid Transit in Toronto levyrapidtransit.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 About this Book 9 Edward J. Levy 11 A Note from the Neptis Foundation 13 Author’s Note 16 Author’s Guiding Principle: The Need for a Network 18 Executive Summary 24 PART ONE: EARLY PLANNING FOR RAPID TRANSIT 1909 – 1945 CHAPTER 1: THE BEGINNING OF RAPID TRANSIT PLANNING IN TORONTO 25 1.0 Summary 26 1.1 The Story Begins 29 1.2 The First Subway Proposal 32 1.3 The Jacobs & Davies Report: Prescient but Premature 34 1.4 Putting the Proposal in Context CHAPTER 2: “The Rapid Transit System of the Future” and a Look Ahead, 1911 – 1913 36 2.0 Summary 37 2.1 The Evolving Vision, 1911 40 2.2 The Arnold Report: The Subway Alternative, 1912 44 2.3 Crossing the Valley CHAPTER 3: R.C. -

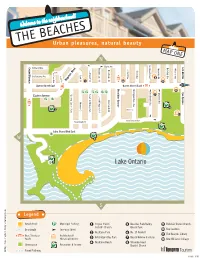

90Ab-The-Beaches-Route-Map.Pdf

THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP ONE N Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Coxw Dixon Ave Bell Brookmount Rd Wheeler Ave Wheeler Waverley Rd Waverley Ashland Ave Herbert Ave Boardwalk Dr Lockwood Rd Elmer Ave efair Ave efair O r c h ell A ell a r d Lark St Park Blvd Penny Ln venu Battenberg Ave 8 ingston Road K e 1 6 9 Queen Street East Queen Street East Woodbine Avenue 11 Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Kippendavie Ave Kippendavie Ave Waverley Rd Waverley Sarah Ashbridge Ave Northen Dancer Blvd Eastern Avenue Joseph Duggan Rd 7 Boardwalk Dr Winners Cir 10 2 Buller Ave V 12 Boardwalk Dr Kew Beach Ave Al 5 Lake Shore Blvd East W 4 3 Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking Corpus Christi Beaches Park/Balmy Bellefair United Church g 1 5 9 Catholic Church Beach Park 10 Kew Gardens . Desi Boardwalk One-way Street d 2 Woodbine Park 6 No. 17 Firehall her 11 The Beaches Library p Bus, Streetcar Architectural/ he Ashbridge’s Bay Park Beach Hebrew Institute S 3 7 Route Historical Interest 12 Kew Williams Cottage 4 Woodbine Beach 8 Waverley Road : Diana Greenspace Recreation & Leisure g Baptist Church Writin Paved Pathway BEACH_0106 THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP TWO N H W Victoria Park Avenue Nevi a S ineva m Spruc ca Lee Avenue Kin b Wheeler Ave Wheeler Balsam Ave ly ll rbo Beech Ave Willow Ave Av Ave e P e Crown Park Rd gs Gle e Hill e r Isleworth Ave w o ark ark ug n Manor Dr o o d R d h R h Rd Apricot Ln Ed Evans Ln Blvd Duart Park Rd d d d 15 16 18 Queen Street East 11 19 Balsam Ave Beech Ave Willow Ave Leuty Ave Nevi Hammersmith Ave Hammersmith Ave Scarboro Beach Blvd Maclean Ave N Lee Avenue Wineva Ave Glen Manor Dr Silver Birch Ave Munro Park Ave u Avion Ave Hazel Ave r sew ll Fernwood Park Ave Balmy Ave e P 20 ood R ark ark Bonfield Ave Blvd d 0 Park Ave Glenfern Ave Violet Ave Selwood Ave Fir Ave 17 12 Hubbard Blvd Silver Birch Ave Alfresco Lawn 14 13 E Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking g 13 Leuty Lifesaving Station 17 Balmy Beach Club . -

Cincinnati's Hard-Won Modern Tram Revival

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com NOVEMBER 2016 NO. 947 CINCINNATI’S HARD-WON MODERN TRAM REVIVAL InnoTrans: The world’s greatest railway showcase Russian cities’ major low-floor orders Stadler and Solaris join for tram bids Doha Metro tunnelling is complete ISSN 1460-8324 £4.25 Berlin Canada’s ‘Radial’ 11 Above and below the Exploring Ontario’s streets of the capital Halton County line 9 771460 832043 LRT MONITOR TheLRT MONITOR series from Mainspring is an essential reference work for anyone who operates in the world’s light and urban rail sectors. Featuring regular updates in both digital and print form, the LRT Monitor includes an overview of every established line and network as well as details of planned schemes and those under construction. POLAND POZNAŃ Tramways play an important role in one of of the main railway station. Poland’s biggest and most historic cities, with In 2012 a line opened to the east of the city, the first horse-drawn tramline opening in 1880. with an underground section containing two An overview Electrification followed in 1898. sub-surface stations and a new depot. The The network was badly damaged during World reconstruction of Kaponiera roundabout, an A high-quality War Two, resuming operations in 1947 and then important tram junction, is set for completion in of the system’s only east of the river Warta. Service returned to 2016. When finished, it will be a three-level image for ease the western side of the city in 1952 with the junction, with a PST interchange on the lower development, opening of the Marchlewski bridge (now named level. -

Inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register -1627 Danforth Avenue

~TORONTO REPORT FOR ACTION Inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register - 1627 Danforth Avenue Date: April 4, 2019 To: Toronto Preservation Board Toronto and East York Community Council From: Senior Manager, Heritage Preservation Services, Urban Design, City Planning Wards: Ward 19 – Beaches-East York SUMMARY This report recommends that City Council include the property at 1627 Danforth Avenue on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register. The site contains a complex known historically as the Danforth Carhouse, which is currently owned by the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC). It was developed beginning in 1914 by the Toronto Civic Railways (TCR), expanded by the Toronto Transportation Commission (forerunner to today's TTC) and the TTC and currently used as offices and staff facilities for TTC personnel. In 2015, City Council requested that the property at 1627 Danforth Avenue be researched and evaluated for inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register. It has been identified for its potential cultural heritage value in the Danforth Avenue Planning Study (2018). It is the selected site for a police station consolidating 54 and 55 Divisions. The property at 1627 Danforth Avenue is part of a Master Plan study being undertaken by CreateTO to guide the redevelopment of the site as a multi-use civic hub for the Toronto Transit Commission, the Toronto Police Service and the Toronto Public Library as the key anchor tenants, which will incorporate and adaptively reuse the Danforth Carhouse. RECOMMENDATIONS The Senior Manager, Heritage Preservation Services, Urban Design City Planning recommends that: 1. City Council include the property at 1627 Danforth Avenue on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register in accordance with the Statement of Significance (Reasons for Inclusion), attached as Attachment 3 to the report (April 4, 2019) from the Senior Manager, Heritage Preservation Services, Urban Design, City Planning. -

THE STREET RAILWAY JOURNAL [Vol X

Vol. X. MEW YORK $ CHICAGO, JULY. JVo. 7. u CINCINNATI AND ITS STREET RAILWAYS. b Cincinnati is the city of the double trolley, full connections. Most of the difficulties experie grooved girder rail, and of vestibuled cars. There are double trolley in the early history of these lines have" been also other characteristic features pertaining to the street overcome, and, with the exception of the fact that the railway systems of the city, which will have attention overhead construction is a little more complicated and later on. unsightly, and that it requires a little more attention on Although the employment of the girder rail, and the the part of the conductor to handle the trolley poles at use of the vestibules were compulsory, and in the face of switches and crossings, there are no serious difficulties earnest protest by the managers of the Cincinnati Street that have not been overcome. Railway Company and the Mount Adams & Eden Park The principal difficulties which were first encountered Inclined Railway, their employment has been attended were those of providing overhead crossings and switches, with less difficulties than was originally supposed, while to prevent short circuits at the crossing of positive and FIG. 1.— EDEN PARK VIADUCT— MOUNT ADAMS & EDEN PARK INCLINED RAILWAY, CINCINNATI. they have developed a number of commendable features, negative wires. These have been overcome in an ingen- so that the management has now come to regard them ious manner, as will be seen from the accompanying illus- favorably, and has ceased all opposition to their introduc- trations of switches and crossings (Figs. -

125 Years of Toronto Streetcars

125 YEARS OF TORONTO STREETCARS UPPER CANADA RAILWAY SOCIETY BOX 122 STATION "A" TORONTO, ONTARIO One of the Belgian streetcars which recently began running on a new line at the Grand Cypress Resort near Orlando, Florida. See article 'The End of an Era' in this issue. , --John Fleck Gulf Pulp & Paper Co. 0-6-0 38, on display at Mount Forest, Ont., after being bought by Christian Bell Porcelain. Further details in Feb. 1986 NEWSLETTER. Photo taken April 26, 1986. McCarten lP NFTA LRV 125 has been turned into the world's newest and fanciest 'streetcar diner' outside Hoak's Armor Inn, Hamburg, N.Y. The car was dropped and damaged irreparably while being deliverd to the NFTA shops in Buffalo; a replacement 125 was subsequently built and delivered and the '1st 125', which never turned a wheel in revenue service, was sold to this restaurant, probably for use as a cocktail lounge. July 28, 1986. McCarten SEPTEMBER 1986 3 Years of Urban Rail Transit in Tnronto On Sept. 11, 1986 we think back to the equivalent date in 1861, when Canada's first urban rail passenger service commenced operation: a horsecar service provided by the Toronto Street Railway Company. Mr. Alexander Easton of Philadelphia, a public transit entrepreneur of the day, obtained a 30-year franchise to operate animal powered streetcar service from the City of Toronto on March 26, 1861. The TSR was organized in May of that year with A. Easton as President and Alexander Bleekly and Daniel Smith as Directors. The franchise provided for service on at least a 30-minute headway, with the daily operating period to be 16 hours a day in summer and 14 hours a day in winter (the spring and fall seasons do not appear to have been recognized). -

923466Magazine1final

www.globalvillagefestival.ca Global Village Festival 2015 Publisher: Silk Road Publishing Founder: Steve Moghadam General Manager: Elly Achack Production Manager: Bahareh Nouri Team: Mike Mahmoudian, Sheri Chahidi, Parviz Achak, Eva Okati, Alexander Fairlie Jennifer Berry, Tony Berry Phone: 416-500-0007 Email: offi[email protected] Web: www.GlobalVillageFestival.ca Front Cover Photo Credit: © Kone | Dreamstime.com - Toronto Skyline At Night Photo Contents 08 Greater Toronto Area 49 Recreation in Toronto 78 Toronto sports 11 History of Toronto 51 Transportation in Toronto 88 List of sports teams in Toronto 16 Municipal government of Toronto 56 Public transportation in Toronto 90 List of museums in Toronto 19 Geography of Toronto 58 Economy of Toronto 92 Hotels in Toronto 22 History of neighbourhoods in Toronto 61 Toronto Purchase 94 List of neighbourhoods in Toronto 26 Demographics of Toronto 62 Public services in Toronto 97 List of Toronto parks 31 Architecture of Toronto 63 Lake Ontario 99 List of shopping malls in Toronto 36 Culture in Toronto 67 York, Upper Canada 42 Tourism in Toronto 71 Sister cities of Toronto 45 Education in Toronto 73 Annual events in Toronto 48 Health in Toronto 74 Media in Toronto 3 www.globalvillagefestival.ca The Hon. Yonah Martin SENATE SÉNAT L’hon Yonah Martin CANADA August 2015 The Senate of Canada Le Sénat du Canada Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4 K1A 0A4 August 8, 2015 Greetings from the Honourable Yonah Martin Greetings from Senator Victor Oh On behalf of the Senate of Canada, sincere greetings to all of the organizers and participants of the I am pleased to extend my warmest greetings to everyone attending the 2015 North York 2015 North York Festival. -

Mass Transit and the Failure of Private Ownership: the Case of Toronto in the Early Twentieth Century Michael J

Document generated on 09/24/2021 12:16 a.m. Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine Mass Transit and the Failure of Private Ownership: The Case of Toronto in the Early Twentieth Century Michael J. Doucet Number 3-77, February 1978 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1019498ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1019498ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine ISSN 0703-0428 (print) 1918-5138 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Doucet, M. J. (1978). Mass Transit and the Failure of Private Ownership: The Case of Toronto in the Early Twentieth Century. Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, (3-77), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.7202/1019498ar All Rights Reserved © Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 1978 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ MASS TRANSIT AND THE FAILURE OF PRIVATE OWNERSHIP: THE CASE OF TORONTO IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY* Michael J. Doucet During the last half of the nineteenth century several developments in the field of urban mass transit helped to greatly alter the spatial structure and the way of life in cities in Europe and North America. -

Title Subject Author Publ Abbr Date Price Format Size Binding Pages

Title Subject Author Publ abbr Date Price Cond Sub title Notes ISBN Number Qty Size Pages Format Binding 100 Jahre Berner-Oberland-Bahnen; EK-Special 18 SWISS,NG Muller,Jossi EKV 1990 $24.00 V 4 SC 164 exc Die Bahnen der Jungfrauregiongerman text EKS18 1 100 Trains, 100 Years, A Century of Locomotives andphotos Trains Winkowski, SullivanCastle 2005 $20.00 V 5 HC 167 exc 0-7858-1669-0 1 100 Years of Capital Traction trolleys King Taylor 1972 $75.00 V 4 HC The329 StoryExc of Streetcars in the Nations Capital 72-97549 1 100 Years of Steam Locomotives locos Lucas Simmons-Boardman1957 $50.00 V 4 HC 278 exc plans & photos 57-12355 1 125 Jahre Brennerbahn, Part 2 AUSTRIA Ditterich HMV 1993 $24.00 V 4 T 114 NEW Eisenbahn Journal germanSpecial text,3/93 color 3-922404-33-2 1 1989 Freight Car Annual FREIGHT Casdorph SOFCH 1989 $40.00 V 4 ST 58 exc Freight Cars Journal Monograph No 11 0884-027X 1 1994-1995 Transit Fact Book transit APTA APTA 1995 $10.00 v 2 SC 174 exc 1 20th Century NYC Beebe Howell North 1970 $30.00 V 4 HC 180 Exc 0-8310-7031-5 1 20th Century Limited NYC Zimmermann MBI 2002 $34.95 V 4 HC 156 NEW 0-7603-1422-5 1 30 Years Later, The Shore Line TRACTIN Carlson CERA 1985 $60.00 V 4 ST 32 exc Evanston - Waukegan 1896-1955 0-915348-00-4 1 35 Years, A History of the Pacific Coast Chapter R&LHS PCC R&LHS PCC R&LHS 1972 V 4 ST 64 exc 1 36 Miles of Trouble VT,SHORTLINES,EASTMorse Stephen Greene1979 $10.00 v 2 sc 43 exc 0-8289-0182-1 1 3-Axle Streetcars, Volume One trolley Elsner NJI 1994 $250.00 V 4 SC 178 exc #0539 of 1000 0-934088-29-2