Procedure for Rescue Slow Or Stuck Fermentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concepts in Wine Chemistry

THIRD EDITION Concepts IN Wine Chemistry YAIR MARGALIT, Ph.D. The Wine Appreciation Guild San Francisco Contents Introduction ix I. Must and Wine Composition 1 A. General Background 3 B. Sugars 5 C. Acids 11 D. Alcohols 22 E. Aldehydes and Ketones 30 F. Esters 32 G. Nitrogen Compounds 34 H. Phenols 43 I. Inorganic Constituents 52 References 55 n. Fermentation 61 A. General View 63 B. Chemistry of Fermentation 64 C. Factors Affecting Fermentation 68 D. Stuck Fermentation 77 E. Heat of Fermentation 84 F. Malolactic Fermentation 89 G. Carbonic Maceration 98 References 99 v III. Phenolic Compounds 105 A. Wine Phenolic Background 107 B. Tannins 120 C. Red Wine Color 123 D. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Grapes 139 References 143 IV. Aroma and Flavor 149 A. Taste 151 B. Floral Aroma 179 C. Vegetative Aroma 189 D. Fruity Aroma 194 E. Bitterness and Astringency 195 F. Specific Flavors 201 References 214 V. Oxidation and Wine Aging 223 A. General Aspects of Wine Oxidation 225 B. Phenolic Oxidation 227 C. Browning of White Wines 232 D. Wine Aging 238 References 253 VI. Oak Products 257 A. Cooperage 259 B. Barrel Aging 274 C. Cork 291 References 305 vi VH. Sulfur Dioxide 313 A. Sulfur-Dioxide as Food Products Preservative 315 B. Sulfur-Dioxide Uses in Wine 326 References 337 Vm. Cellar Processes 341 A. Fining 343 B. Stabilization 352 C. Acidity Adjustment 364 D. Wine Preservatives 372 References 382 IX. Wine Faults 387 A. Chemical Faults 389 B. Microbiological Faults 395 C. Summary ofFaults 402 References 409 X. -

Phenolic Compounds As Markers of Wine Quality and Authenticity

foods Review Phenolic Compounds as Markers of Wine Quality and Authenticity Vakare˙ Merkyte˙ 1,2 , Edoardo Longo 1,2,* , Giulia Windisch 1,2 and Emanuele Boselli 1,2 1 Faculty of Science and Technology, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Piazza Università 5, 39100 Bozen-Bolzano, Italy; [email protected] (V.M.); [email protected] (G.W.); [email protected] (E.B.) 2 Oenolab, NOI Techpark South Tyrol, Via A. Volta 13B, 39100 Bozen-Bolzano, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0471-017691 Received: 29 October 2020; Accepted: 28 November 2020; Published: 1 December 2020 Abstract: Targeted and untargeted determinations are being currently applied to different classes of natural phenolics to develop an integrated approach aimed at ensuring compliance to regulatory prescriptions related to specific quality parameters of wine production. The regulations are particularly severe for wine and include various aspects of the viticulture practices and winemaking techniques. Nevertheless, the use of phenolic profiles for quality control is still fragmented and incomplete, even if they are a promising tool for quality evaluation. Only a few methods have been already validated and widely applied, and an integrated approach is in fact still missing because of the complex dependence of the chemical profile of wine on many viticultural and enological factors, which have not been clarified yet. For example, there is a lack of studies about the phenolic composition in relation to the wine authenticity of white and especially rosé wines. This review is a bibliographic account on the approaches based on phenolic species that have been developed for the evaluation of wine quality and frauds, from the grape varieties (of V. -

Understanding Problem Fermentations – a Review

Understanding Problem Fermentations – A Review S. Malherbe, F.F. Bauer and M. Du Toit* Institute for Wine Biotechnology, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland, 7602, South Africa Submitted for publication: July 2007 Accepted for publication: September 2007 Key words: Problem Fermentations, Alcoholic Fermentation, Malolactic Fermentation, Analytical Techniques, Chemometrics. Despite advances in winemaking technology and improvements in fermentation control, problem alcoholic and malolactic fermentations remain a major oenological concern worldwide. This is due to possible depreciation of product quality and its consequent negative economic impact. Various factors have been identified and studied over the years, yet the occurrence of fermentation problems persists. The synergistic effect of the various factors amongst each other provides additional challenges for the study of such fermentations. This literature review summarises the most frequently studied causes of problematic alcoholic and malolactic fermentations and in addition provides a summary of established and some potential new analytical technologies to monitor and investigate the phenomenon of stuck and sluggish fermentations. INTRODUCTION Kunkee, 1985; Bely et al., 1990), vitamin deficiency, especial- Alcoholic fermentation, the conversion of the principal grape ly thiamine (Peynaud and Lafourcade, 1977; Ough et al., 1989; sugars, glucose and fructose, to ethanol and carbon dioxide is Salmon, 1989), oxygen deficiency (Thomaset al., 1978; Traverso conducted by yeasts -

Guide to White Wine Making

Goal of this Manual: To make Great wine at home in your first try! It is highly recommended that this paper be read through completely before you start to make your wine. Wine-making is made up of a series of consecutive steps which build on and directly affect each other from the very beginning to the very end. In order to make the best wine possible you will need to make the best decisions possible at each of these steps, and in order to do that, you will need to have a general understanding of the overall process as a whole. Table of Contents Introduction Page 4 Chapter 1: Preparation & Preplanning Page 6 Chapter 2: Prepare the juice for fermentation Page 8 2.1) Prepare to Fill the Press: Crush and De-Stem the Grapes, or Whole Clusters 2.2) Let’s Clean the Slate – Adding SO2 During Processising 2.3) Fill the Press: Now or Later 2.4) Press the Grapes! 2.5) Pressing 2.6) Refining our Pressed Juice: Settling Out the Solids 2.7) Preemptive Fining 2.8) Test and Adjust the Juice Chapter 3: Add the Yeast and Begin Fermentation Page 25 3.1) Choose Your Yeast 3.2) Hydrate with Go-Ferm 3.3) "Co-Inoculation" (advanced technique) Chapter 4: Monitor Fermentation Page 28 4.1) Stir Daily 4.2) Yeast Nutrition During Fermentation 4.3) Fermentation Temperature 4.4) Monitoring your Sugars, Timing the End of Fermentation Chapter 5: Malolactic Fermentation (“MLF”) Page 34 5.1) Malolactic Fermentation Copyright 2009 MoreFlavor!, Inc Page | 2 5.2) Prepare and add the ML bacterial culture into the wine 5.3) Manageing the MLF 5.4) After 2-3 weeks, begin checking -

2009 AWRI Annual Report 2009 45 Financial Report – Director’S Report

www.awri.com.au BOARD MEMBERS THE COMPANY The AWRI’s laboratories and offices are housed in the Wine Innovation Central Building of the Dr J.W. Stocker AO BMedSc, MBBS, PhD, FRACP, FTSE The Australian Wine Research Institute Ltd was incor- Wine Innovation Cluster (WIC). The WIC is located Chairman–Elected a member under Clause 25.2(d) porated on 27 April 1955. It is a company limited by within an internationally renowned research of the Constitution (from 1 January 2009) guarantee that does not have a share capital. cluster on the Waite Precinct at Urrbrae in the Adelaide foothills, on land leased from The Mr J.F. Brayne, BAppSc(Wine Science) The Constitution of The Australian Wine Research University of Adelaide. Collocated in the Wine Elected a member under Clause 25.2(d) Institute Ltd (AWRI) sets out in broad terms the Innovation Central Building with the AWRI is of the Constitution (from 1 January 2009) aims of the AWRI. In 2006, the AWRI implemented grape and wine scientists from The University of its ten-year business plan Towards 2015, and stated Adelaide and the South Australian Research and Mr P.D. Conroy, LLB(Hons), BCom its purpose, vision, mission and values: Development Institute. The parties in the Wine Elected a member under Clause 25.2(c) Innovation Cluster, who are accommodated over of the Constitution Purpose three buildings, include also CSIRO Plant Industry To contribute substantially in a measurable way to and Provisor Pty Ltd. Mr P.J. Dawson, BSc, BAppSc(Wine Science) the ongoing success of the Australian grape and Elected a member under Clause 25.2(d) wine sector Along with the WIC parties mentioned, the of the Constitution AWRI is clustered with the following research Vision and teaching organisations: Australian Centre Mr G.R. -

Wine Fermentation

Wine Fermentation Edited by Harald Claus Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Fermentation www.mdpi.com/journal/fermentation Wine Fermentation Wine Fermentation Special Issue Editor Harald Claus MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Harald Claus Johannes Gutenberg-University of Mainz Germany Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Fermentation (ISSN 2311-5637) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ fermentation/special issues/wine fermentation) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03897-674-5 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03897-675-2 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Harald Claus. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Harald Claus Wine Fermentation Reprinted from: Fermentation 2019, 5, 19, doi:10.3390/fermentation5010019 ............. 1 Farhana R Pinu Grape and Wine Metabolomics to Develop New Insights Using Untargeted and Targeted Approaches Reprinted from: Fermentation 2018, 4, 92, doi:10.3390/fermentation4040092 ............ -

A Comparison of Legislation About Wine- Making Additives and Processes

A comparison of legislation about wine- making additives and processes Vashti Christina Galpin Assignment submitted in partial requirement for the Cape Wine Master Diploma February 2006 Abstract This document presents a comparison of legislation about the additives and pro- cesses that can be used in winemaking, which are collectively known as oenolog- ical practices. It considers five jurisdictions: South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, the United States and the European Union. The comparison covers the differ- ent styles of legislation, details of which oenological practices are permitted, the relationship between legislation about quality and that about oenological practices, regimes that limit additive use such as organic wine production and environmentally- friendly wine production (specifically the South African Integrated Production of Wine Scheme), regulation of wine importation, multilateral and EU bilateral wine trade agreements, and labelling of additives. The comparison shows that some basic practices such as alcohol increase by addition of substances, sweetening and deacidification and/or acidification are common to all five jurisdictions. For most functions of additives, the legislation of each jurisdiction permits some substance or process to achieve that function. Two major functions for which there are differences are type of wooding permitted, and the addition of flavour extracted from grapes and colouring. There are also differ- ences in the specific additives and processes that are permitted. There are a number of different approaches for the import of wine from requiring imported wine to use the same oenological practices as the wines of the country into which it is imported, to the EU’s approach of bilateral wine trade agreements with individual countries that cover permitted oenological practices, and the multilat- eral Mutual Acceptance Agreement on Oenological Practices. -

Agreement for Industry Capability Building Activities and Research and Development Program 2013-2017

Agreement for Industry Capability Building Activities and Research and Development Program 2013-2017 Final Report to Wine Australia Research Organisation: The Australian Wine Research Institute Date: 22 September 2017 1 Date: 22 September 2017 Disclaimer/Copyright Statement: This document has been prepared by The Australian Wine Research Institute ("the AWRI") as part of fulfilment of obligations towards the Project Agreement AWR 1305 and is intended to be used solely for that purpose and unless expressly provided otherwise does not constitute professional, expert or other advice. The information contained within this document ("Information") is based upon sources, experimentation and methodology which at the time of preparing this document the AWRI believed to be reasonably reliable and the AWRI takes no responsibility for ensuring the accuracy of the Information subsequent to this date. No representation, warranty or undertaking is given or made by the AWRI as to the accuracy or reliability of any opinions, conclusions, recommendations or other information contained herein except as expressly provided within this document. No person should act or fail to act on the basis of the Information alone without prior assessment and verification of the accuracy of the Information. To the extent permitted by law and except as expressly provided to the contrary in this document all warranties whether express, implied, statutory or otherwise, relating in any way to the Information are expressly excluded and the AWRI, its officer, employees and contractors shall not be liable (whether in contract, tort, under any statute or otherwise) for loss or damage of any kind (including direct, indirect and consequential loss and damage of business revenue, loss or profits, failure to realise expected profits or savings or other commercial or economic loss of any kind), however arising out of or in any way related to the Information, or the act, failure, omission or delay in the completion or delivery of the Information. -

MAKING WINE at HOME.Doc

689 West North Avenue (North & 83 Plaza) Elmhurst, Illinois 60126 (630) 834-0507 or (800) 226- BREW [email protected] www.chicagolandwinemakers.com MAKING WINE AT HOME CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW............................................Page 2 EQUIPMENT LIST..........................................................................Page 3 RECIPE DISCUSSION...................................................................Page 4 USING SULFITE..............................................................................Page 4 USING THE HYDROMETER.........................................................Page 5 BATCH PREPARATION.................................................................Page 6 YEAST STARTER FOR WINE.......................................................Page 7 FERMENTATION OF WINE..........................................................Page 8 BULK AGING...................................................................................Page 10 PREPARING FOR BOTTLING......................................................Page 12 BOTTLING THE WINE..................................................................Page 14 WINEMAKERS GLOSSARY.........................................................Page 16 INTRODUCTION The practice of fermentation to make alcohol can be traced to at least 5000 years ago. It would seem that almost every culture devised ways to ferment one thing or another in an amazing variety. Although honey and various grains were used (sometimes in combination with fruit), wine made from grapes -

Gofermentor Jr Operating Manual

Professional winemaking for the serious enthusiast and microvinification researcher. Make wine using real grapes instead of juice for award-winning results. Advanced technology eliminates all the mess and cleaning. Completely self-contained. Does not require a press. GOFERMENTOR JR OPERATING MANUAL GOfermentor is a registered trademark. US patent 9,260,682, 9,611,452, France 3013726, Australia 2014268161, other foreign registrations pending. Operating Manual ©2019-2020 Version 3.0 June1, 2020 www.GOfermentorJR.com 2 CONTENTS WHAT IS THE GOFERMENTOR? ..................................................................................................................................... 4 GOFERMENTOR JR ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 COMPONENTS ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 OPTIONAL .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 DISPOSABLES ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 YOU WILL NEED TO PROVIDE..................................................................................................................................... 4 INITIAL EQUIPMENT SETUP -

Understanding Problem Fermentations–A Review

Understanding Problem Fermentations – A Review S. Malherbe, F.F. Bauer and M. Du Toit* Institute for Wine Biotechnology, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland, 7602, South Africa Submitted for publication: July 2007 Accepted for publication: September 2007 Key words: Problem Fermentations, Alcoholic Fermentation, Malolactic Fermentation, Analytical Techniques, Chemometrics. Despite advances in winemaking technology and improvements in fermentation control, problem alcoholic and malolactic fermentations remain a major oenological concern worldwide. This is due to possible depreciation of product quality and its consequent negative economic impact. Various factors have been identified and studied over the years, yet the occurrence of fermentation problems persists. The synergistic effect of the various factors amongst each other provides additional challenges for the study of such fermentations. This literature review summarises the most frequently studied causes of problematic alcoholic and malolactic fermentations and in addition provides a summary of established and some potential new analytical technologies to monitor and investigate the phenomenon of stuck and sluggish fermentations. INTRODUCTION Kunkee, 1985; Bely et al., 1990), vitamin deficiency, especial- Alcoholic fermentation, the conversion of the principal grape ly thiamine (Peynaud and Lafourcade, 1977; Ough et al., 1989; sugars, glucose and fructose, to ethanol and carbon dioxide is Salmon, 1989), oxygen deficiency (Thomaset al., 1978; Traverso conducted by yeasts -

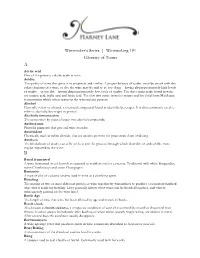

Winemaking 101 Glossary of Terms a Acetic Acid One of the Primary Volatile Acids in Wine

Winemaker’s Series | Winemaking 101 Glossary of Terms A Acetic acid One of the primary volatile acids in wine. Acidity The quality of wine that gives it its crispiness and vitality. A proper balance of acidity must be struck with the other elements of a wine, or else the wine may be said to be too sharp – having disproportionately high levels of acidity – or too flat – having disproportionately low levels of acidity. The three main acids found in wine are tartaric acid, malic acid and lactic acid. The first two come from the grapes and the third from Malolactic fermentation which often occurs in the winemaking process. Alcohol Generally refers to ethanol, a chemical compound found in alcoholic beverages. It is also commonly used to refer to alcoholic beverages in general. Alcoholic fermentation The conversion by yeast of sugar into alcohol compounds Anthocyanin Phenolic pigments that give red wine its color. Antioxidant Chemicals, such as sulfur dioxide, that are used to prevent the grape must from oxidizing. Autolysis The breakdown of dead yeast cells (or lees) and the process through which desirable or undesirable traits maybe imparted to the wine. B Barrel fermented A wine fermented in oak barrels as opposed to stainless steel or concrete. Traditional with white Burgundies, some Chardonnays and some Champagne. Bentonite A type of clay of volcanic origins used in wine as a clarifying agent. Blending The mixing of two or more different parcels of wine together by winemakers to produce a consistent finished wine that is ready for bottling. Laws generally dictate what wines can be blended together, and what is subsequently printed on the wine label.