May Be Xeroxed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

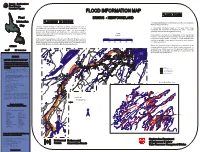

FLOOD INFORMATION MAP FLOOD ZONES Flood BRIGUS - NEWFOUNDLAND

Canada - Newfoundland Flood Damage Reduction Program FLOOD INFORMATION MAP FLOOD ZONES Flood BRIGUS - NEWFOUNDLAND Information FLOODING IN BRIGUS A "designated floodway" (1:20 flood zone) is the area subject to the most frequent flooding. Map Flooding causes damage to personal property, disrupts the lives of individuals and communities, and can be a threat to life itself. Continuing Beth A "designated floodway fringe" (1:100 year flood zone) development of flood plain increases these risks. The governments of une' constitutes the remainder of the flood risk area. This area Canada and Newfoundland and Labrador are sometimes asked to s Po generally receives less damage from flooding. compensate property owners for damage by floods or are expected to find Scale nd solutions to these problems. (metres) No building or structure should be erected in the "designated floodway" since extensive damage may result from deeper and While most of the past flood events on Lamb's Brook in Brigus have been more swiftly flowing waters. However, it is often desirable, and caused by a combination of high flows and ice jams at hydraulic structures may be acceptable, to use land in this area for agricultural or floods can occur due to heavy rainfall and snow melt. This was the case in 0 200 400 600 800 1000 recreational purposes. January 1995 when the Conception Bay Highway was flooded. Within the "floodway fringe" a building, or an alteration to an BRIGUS existing building, should receive flood proofing measures. A variety of these may be used, e.g.. the placing of a dyke around Canada Newfoundland the building, the construction of a building on raised land, or by Brigus the special design of a building. -

Striped Bass (Morone Saxatilis) Population Characteristics and Spawning Assessment in the Bouctouche and Cocagne Rivers

STRIPED BASS (MORONE SAXATILIS) POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS AND SPAWNING ASSESSMENT IN THE BOUCTOUCHE AND COCAGNE RIVERS PREPARED BY: CHARLES COMEAU, NATHALIE LEBLANC-POIRIER, MICHELLE MAILLET, DONALD ALEXANDER PRESENTED TO: THE SOUTHEASTERN ANGLERS ASSOCIATION WILDLIFE TRUST FUND FISHERIES AND OCEANS CANADA JULY 2013 1. INTRODUCTION Striped bass (Morone saxatilis) is a native anadromous fish species of the North American Atlantic coastline that spawns in fresh or brackish water. In the Bay of Fundy and Gulf of St Lawrence watersheds, spawning occurs in May and June. Juvenile Striped bass then migrate downstream to brackish waters and eventually salt water to feed and grow until they have reached maturity, a process that normally takes three to four years. Striped bass was considered a commercially important fish before it was designated as a threatened species by COSEWIC (the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada) in November 2004. However, because there was such a decline in the population, Striped bass met the criteria for being listed as an ‘‘endangered’’ species. The Striped bass population of the Gulf of St Lawrence was ultimately designated as ‘‘threatened’’ because of the high degree of resilience of this species and the high abundance of spawners found prior to the designation. It is therefore important to gather more information on the current Striped bass population in rivers and estuaries draining into the Gulf of St Lawrence. According to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) of Canada, there is no evidence that Striped bass spawn successfully in any other rivers in New Brunswick other than the Northwest Miramichi river (DFO, 2011). -

Regulatory and Institutional Developments in the Ontario Wine and Grape Industry

International Journal of Wine Research Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article OrigiNAL RESEARCH Regulatory and institutional developments in the Ontario wine and grape industry Richard Carew1 Abstract: The Ontario wine industry has undergone major transformative changes over the last Wojciech J Florkowski2 two decades. These have corresponded to the implementation period of the Ontario Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) Act in 1999 and the launch of the Winery Strategic Plan, “Poised for 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Pacific Agri-Food Research Greatness,” in 2002. While the Ontario wine regions have gained significant recognition in Centre, Summerland, BC, Canada; the production of premium quality wines, the industry is still dominated by a few large wine 2Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of companies that produce the bulk of blended or “International Canadian Blends” (ICB), and Georgia, Griffin, GA, USA multiple small/mid-sized firms that produce principally VQA wines. This paper analyzes how winery regulations, industry changes, institutions, and innovation have impacted the domestic production, consumption, and international trade, of premium quality wines. The results of the For personal use only. study highlight the regional economic impact of the wine industry in the Niagara region, the success of small/mid-sized boutique wineries producing premium quality wines for the domestic market, and the physical challenges required to improve domestic VQA wine retail distribution and bolster the international trade of wine exports. Domestic success has been attributed to the combination of natural endowments, entrepreneurial talent, established quality standards, and the adoption of improved viticulture practices. -

Association of Municipal Administators of New Brunswick Annual Report

Association of Municipal Administators of New Brunswick 20 Courtney Street, Douglas (NB) E3G 8A1 Telephone: (506) 453-4229 Fax: (506) 444-5452 E-mail: [email protected] Annual Report 2013-2014 38th Annual General Meeting June 12, 2014 Fredericton, New Brunswick AMANB Table of Contents Item Page Agenda ............................................................................................................................. 2 Board of Directors ....................................................................................................... 3 - 4 Minutes - 37th Annual General Meeting - June 13, 2013 ............................................. 5 - 9 President’s Report ............................................................................................................10 Auditor’s Report ....................................................................................................... 11 - 21 Education Committee Report .................................................................................. 22 - 23 Region 1 Report .............................................................................................................. 24 Region 2 Report .............................................................................................................. 25 Region 3 Report .............................................................................................................. 26 Region 4 Report .............................................................................................................. 27 -

Media Kit the Wines of British Columbia “Your Wines Are the Wines of Sensational!” British Columbia ~ Steven Spurrier

MEDIA KIT THE WINES OF BRITISH COLUMBIA “YOUR WINES ARE THE WINES OF SENSATIONAL!” BRITISH COLUMBIA ~ STEVEN SPURRIER British Columbia is a very special place for wine and, thanks to a handful of hard-working visionaries, our vibrant industry has been making a name for itself nationally and internationally for the past 25 years. “BC WINE OFTEN HAS In 1990, the Vintner’s Quality Alliance (VQA) standard was created to guarantee consumers they A RADICAL FRESHNESS were drinking wine made from 100% BC grown grapes. Today, BC VQA Wines dominate wine sales AND A REMARKABLE in British Columbia, and our wines are finding their way to more places than ever before, winning ABILITY TO DEFY over both critics and consumers internationally. THE CONVENTIONAL CATEGORIES OF TASTE.” The Wines of British Columbia truly are a reflection of the land where the grapes are grown and the exceptional people who craft them. We invite you to join us to savour all that makes the Wines of STUART PIGOTT British Columbia so special. ~ “WHAT I LOVE MOST ABOUT BC WINES IS THEY MIMIC THE PLACE, THEY MIMIC THE PURITY. YOU LOOK OUT AND FEEL THE AIR, TASTE THE WATER AND LOOK AT THE LAKE AND YOU CAN’T HELP BUT BE STRUCK BY A SENSE OF PURITY AND IT CARRIES OVER TO THE WINE. THEY HAVE PURITY AND A SENSE OF WEIGHTLESSNESS WHICH IS VERY ETHEREAL AND CAPTIVATING.” ~ KAREN MACNEIL DID YOU KNOW? • British Columbia’s Vintners Quality Alliance (BC VQA) designation celebrated 25 years of excellence in 2015. • BC’s Wine Industry has grown from just 17 grape wineries in 1990 to more than 275 today (as of January 2017). -

Breakfast Lunch Alternates PM Alternates Dinner Alternates HS

Week 1 McCormick Home Week at a Glance Regular McCormick Spring/Summer 2019 Monday 1 Tuesday 2 Wednesday 3 Thursday 4 Friday 5 Saturday 6 Sunday 7 Breakfast Oatmeal Cream of Wheat w/Bran Oatmeal Oatmeal Oatmeal Oatmeal Oatmeal Scrambled Eggs Breakfast Sliced Cheese Boiled Egg Scrambled Eggs Poached Egg Scrambled Eggs French Toast WW Toast w/Margarine Raspberry Yogurt Muffin WW Toast w/Margarine Buttered Raisin Toast WW Toast w/Margarine WW Toast w/Margarine Crispy Bacon Banana Banana Banana Banana Banana Banana Maple Syrup Banana Lunch Cream of Celery Soup Chicken & Rice Soup Cream Of Mushroom Soup Tomato Juice Pea w/Ham Soup Crm of Tomato & Red Pepper Soup Vegetable Soup Beef Pot Pie Spinach Quiche Cheese Pizza Hamburger w/Condiments BBQ Pulled Pork Cheese & Onion Sandwich Haddock Bites w/Tartar Sauce Diced Turnip California Mixed Vegetables Caesar Salad Potato Chips Sunrise Mixed Vegetables Cucumber Slices Savoury Diced Potatoes Tiger Mousse Orange Sherbet Cinnamon Roll Lettuce & Tomato Slices Nanaimo Bar Choice of Salad Dressing Tomato Parmesan Vanilla Ice Cream Cup Macaroon Madness Butterscotch Ice Cream Alternates Cheddar Cheese w/Fruit Plate Turkey Salad Sandwich Salmon Salad Sandwich Turkey Mandarin Salad Egg Salad Sandwich Pork & Pineapple Stir Fry Ham & Swiss Sliders WW Dinner Roll Pickled Beets Creamy Cucumber Salad WW Dinner Roll Greek Salad w/Feta Steamed Rice Creamy Coleslaw Citrus Fruit Cup Diced Pears Blueberries Fresh Fruit Diced Watermelon Vegetables Stir Fry Mixed Berries Strawberries PM Assorted Diet Drinks Assorted -

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (AZ Listing by Episode Title. Prices Include

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (A-Z listing by episode title. Prices include taxes and shipping within Canada) Catalog is updated at the end of each month. For current month’s listings, please visit: http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/schedule/ Transcript = readable, printed transcript CD = titles are available on CD, with some exceptions due to copyright = book 104 Pall Mall (2011) CD $18 foremost public intellectuals, Jean The Academic-Industrial Ever since it was founded in 1836, Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Complex London's exclusive Reform Club Spelman Rockefeller Professor of (1982) Transcript $14.00, 2 has been a place where Social and Political Ethics, Divinity hours progressive people meet to School, The University of Chicago. Industries fund academic research discuss radical politics. There's In addition to her many award- and professors develop sideline also a considerable Canadian winning books, Professor Elshtain businesses. This blurring of the connection. IDEAS host Paul writes and lectures widely on dividing line between universities Kennedy takes a guided tour. themes of democracy, ethical and the real world has important dilemmas, religion and politics and implications. Jill Eisen, producer. 1893 and the Idea of Frontier international relations. The 2013 (1993) $14.00, 2 hours Milton K. Wong Lecture is Acadian Women One hundred years ago, the presented by the Laurier (1988) Transcript $14.00, 2 historian Frederick Jackson Turner Institution, UBC Continuing hours declared that the closing of the Studies and the Iona Pacific Inter- Acadians are among the least- frontier meant the end of an era for religious Centre in partnership with known of Canadians. -

The Canadian Maritimes

Exclusive UW departure – May 31-June 11, 2020 THE CANADIAN MARITIMES 12 days for $4,997 total price from Seattle ($4,895 air & land inclusive plus $102 airline taxes and fees) ova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince N Edward Island make for a scenic and history-infused journey. We explore fishing villages and port cities, French fortifications and colonial British settlements, and travel to secluded Prince Edward Island and rugged Cape Breton on this classic route. PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND Cape Breton Charlottetown Island Shediac Iona NEW BRUNSWICK Saint John Bay of NOVA SCOTIA Fundy Halifax Map Legend Destination Motorcoach Atlantic Ocean Motorcoach and Ferry Entry/Departure On Day 2, we visit Peggys Point Lighthouse, one of Nova Scotia’s most popular attractions. Avg. High (°F) May Jun Halifax 58 67 Iona 56 66 Day 1: Arrive Halifax, Nova Scotia We arrive today Day 3: Halifax/Saint John, New Brunswick in Halifax, capital of the Canadian province of Nova Today we travel to the scenic Annapolis Valley, a Scotia and a bustling center of commerce and shipping. network of farms, fields, and forests lying between As guests’ arrival times may vary greatly, we have no two mountain ranges in Nova Scotia’s northwest. We Your Small Group Tour Highlights group activities or meals planned for today. stop for a tour at Tangled Garden, where we learn how the workers use the fresh fruit and aromatic Iconic Peggy’s Point Lighthouse • UNESCO site of Lunenburg Day 2: Halifax/Lunenburg/South Shore This herbs cultivated here to create a wide range of pre- • Scenic Annapolis Valley and Grand-Pré National Historic morning we begin our exploration of Canada’s mari- serves, jellies, mustards, and liqueurs. -

Eli's Butter Tart and Salted Caramel Tart Win a FABI 2017 Award

For: The Eli’s Cheesecake Company Contact: Debbie Marchok 6701 West Forest Preserve Drive [email protected] Chicago, IL 60634 773-308-7003 Eli’s Butter Tart and Salted Caramel Tart Win a FABI 2017 Award presented by the National Restaurant Association Restaurant, Hotel-Motel Show® The Eli's Cheesecake Company of Chicago is honored to receive a FABI 2017 Award presented by the National Restaurant Association Restaurant, Hotel-Motel Show® for two of Eli’s newest desserts: Butter Tart and Salted Caramel Tart. FABI Awards recognize innovation in food and beverage products that make an impact on the restaurant industry. Eli’s individually wrapped tarts are handmade with the finest ingredients like Madagascar vanilla, and sea salt caramel made from scratch. Baked in a housemade all-butter pâte sucrée crust, each tart is wrapped to go in a custom, easy-to-merchandise window sleeve. The tarts ship frozen, and are merchandised refrigerated or ambient. Butter Tart Handmade in small batches, Eli’s pastry chef’s take on the classic Canadian Butter Tart offers an upscale dessert experience in a versatile format. This decadent dessert—a sweet, gooey, chewy filling baked in a crisp all-butter pâte sucrée crust—is delicious served warm or cold. Certified Kosher and available in bulk for foodservice or individually wrapped for grab & go applications. 3”/24 pack/2.6 oz. each. Eli’s #240801 Salted Caramel Tart Chef-created in an individual serving size, this decadent tart features a scratch sea salt caramel filling topped with rich milk chocolate ganache sprinkled with sea salt atop a house made all-butter pâte sucrée crust. -

Jamie's Great Britain the Creation of a New British Food Identity

Jamie’s Great Britain: The Creation of a New British Food Identity Bachelorarbeit im Zwei-Fächer-Bachelorstudiengang, Anglistik/Nordamerikanistik der Philosophischen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Hermann Dzingel Erstgutacher: Prof. Dr. Christian Huck Zweitgutachter: Dennis Büscher-Ulbrich Kiel im September 2014 Contents 1. Introduction .....................................................................................................2 2. Cultural Appropriation .....................................................................................4 3. A fragmented British Identity...........................................................................8 4. Identity, Food and the British ..........................................................................9 5. British Food and Television...........................................................................13 6. Jamie Oliver and ‘his’ Great Britain...............................................................15 6.1 Methodology............................................................................................17 6.2 The Opening............................................................................................18 6.3 The East End and Essex.........................................................................20 6.4 The Heart of England ..............................................................................25 6.5 The West of Scotland ..............................................................................28 7. -

Download Spring 2010

2010SpringSummer_Cover:Winter05Cover 11/11/09 11:24 AM Page 1 NATHALIE ABI-EZZI SHERMAN ALEXIE RAFAEL ALVAREZ JESSICA ANTHONY NICHOLSON BAKER CHARLES BEAUCLERK SAMUEL BECKETT G ROVE P RESS CHRISTOPHER R. BEHA THOMAS BELLER MARK BOWDEN RICHARD FLANAGAN HORTON FOOTE ATLANTIC M ONTHLY PRESS JOHN FREEMAN JAMES HANNAHAM TATJANA HAUPTMANN ELIZABETH HAWES SHERI HOLMAN MARY-BETH HUGHES B LACK CAT DAVE JAMIESON ISMAIL KADARE LILY KING DAVID KINNEY MICHAEL KNIGHT G RANTA AND O PEN C ITY DAVID LAWDAY lyP MIKE LAWSON nth r JEFF LEEN o es DONNA LEON A A A A M s ED MACY t t t t c KARL MARLANTES l l l l ti NICK MC DONELL n TERRY MC DONELL a CHRISTOPHER G. MOORE JULIET NICOLSON SOFI OKSANEN P. J. O’ ROURKE ROBERTA PIANARO JOSÉ MANUEL PRIETO PHILIP PULLMAN ROBERT SABBAG MARK HASKELL SMITH MARTIN SOLARES MARGARET VISSER GAVIN WEIGHTMAN JOSH WEIL TOMMY WIERINGA G. WILLOW WILSON ILYON WOO JOANNA YAS ISBN 978-1-55584-958-0 ISBN 1-55584-958-X GROVE/ATLANTIC, INC. 50000 841 BROADWAY NEW YORK, NY 10003 9 781555 849580 ATLANTIC MONTHLY PRESS HARDCOVERS APRIL This novel, written by a Marine veteran over the course of thirty years, is a remarkable literary discovery: a big, powerful, timeless saga of men in combat MATTERHORN A Novel of the Vietnam War Karl Marlantes PHOTO COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR • Marlantes is a graduate of Yale University and a Rhodes Scholar who went on to serve as a Marine “Matterhorn is one of the most powerful and moving novels about combat, lieutenant in Vietnam, where he the Vietnam War, and war in general that I have ever read.” —Dan Rather was highly decorated ntense, powerful, and compelling, Matterhorn is an epic war novel in the • Matterhorn will be copublished tradition of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and James Jones’s with El León Literary Arts IThe Thin Red Line. -

Canadian Curriculum Guide 2016

he comparisons with the United States are frequent, however the differences and distinct personalities are exciting. Like the U.S., Canada is a very young country in comparison to the rest of the world. Like the U.S, it has a British heritage, but the French were there first and are one of the two founding nations. Both countries became new homes to the world’s immigrants, creating an exciting display of culture and style. Both countries were also built on a foundation of First Nations people, those who originally inhabited their soils. We not only share the world’s longest unprotected border with our neighbor to the north, we also share many values, diversity, celebrations, and great pride and patriotism. We share concerns for other nations, and a willingness to extend a hand. Our differences make our friendship all the more intriguing. Our bonds grow as we explore and appreciate their natural beauty of waterfalls, glaciers, abundant wildlife and breathtaking vistas. We’re similar in size, however with a fraction of our population, they make us envious of their open spaces and relaxed attitudes. Canada is so familiar, so safe… yet so fascinatingly. Who wouldn’t be drawn by strolls throughout the ancient city of Quebec, hiking or biking in Alberta or British Columbia, breathing the fresh air of Nova Scotia sweeping in from the Atlantic, or setting sail from Prince Edward Island? How can you not envy a neighbor who furnishes ten times more breathing room and natural beauty per person than we do? How cool to have a neighbor with one city that boasts as many polar bears as residents.