Regulatory and Institutional Developments in the Ontario Wine and Grape Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author' s Permission) p CLASS ACTS: CULINARY TOURISM IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR by Holly Jeannine Everett A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Folklore Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2005 St. John's Newfoundland ii Class Acts: Culinary Tourism in Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract This thesis, building on the conceptual framework outlined by folklorist Lucy Long, examines culinary tourism in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. The data upon which the analysis rests was collected through participant observation as well as qualitative interviews and surveys. The first chapter consists of a brief overview of traditional foodways in Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as a summary of the current state of the tourism industry. As well, the methodology which underpins the study is presented. Chapter two examines the historical origins of culinary tourism and the development of the idea in the Canadian context. The chapter ends with a description of Newfoundland and Labrador's current culinary marketing campaign, "A Taste of Newfoundland and Labrador." With particular attention to folklore scholarship, the course of academic attention to foodways and tourism, both separately and in tandem, is documented in chapter three. The second part of the thesis consists of three case studies. Chapter four examines the uses of seal flipper pie in hegemonic discourse about the province and its culture. Fried foods, specifically fried fish, potatoes and cod tongues, provide the starting point for a discussion of changing attitudes toward food, health and the obligations of citizenry in chapter five. -

How to Buy Eiswein Dessert Wine

How to Buy Eiswein Dessert Wine Eiswein is a sweet dessert wine that originated in Germany. This "late harvest" wine is traditionally pressed from grapes that are harvested after they freeze on the vine. "Eiswein" literally means "ice wine," and is called so on some labels. If you want to buy eiswein, know the country and the method that produced the bottle to find the best available "ice wine" for your budget. Does this Spark an idea? Instructions 1. o 1 Locate a local wine store or look on line for wine sellers who carry eiswein. o 2 Look for a bottle that fits your price range. German and Austrian Eisweins, which follow established methods of harvest and production, are the European gold standard. However, many less expensive, but still excellent, ice wines come from Austria, New Zealand, Slovenia, Canada and the United States. Not all producers let grapes freeze naturally before harvesting them at night. This time-honored and labor-intensive method of production, as well as the loss of all but a few drops of juice, explains the higher price of traditionally produced ice wine. Some vintners pick the grapes and then artificially freeze them before pressing. Manage Cellar, Share Tasting Notes Free, powerful, and easy to use! o 3 Pick a colorful and fragrant bouquet. Eiswein is distinguished by the contrast between its fragrant sweetness and acidity. A great eiswein is both rich and fresh. Young eisweins have tropical fruit, peach or berry overtones. Older eisweins suggest caramel or honey. Colors can range from white to rose. -

Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada

MARKET INDICATOR REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2013 Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada Source: Planet Retail, 2012. Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INSIDE THIS ISSUE Canada’s population, estimated at nearly 34.9 million in 2012, Executive Summary 2 has been gradually increasing and is expected to continue doing so in the near-term. Statistics Canada’s medium-growth estimate for Canada’s population in 2016 is nearly 36.5 million, Market Trends 3 with a medium-growth estimate for 2031 of almost 42.1 million. The number of households is also forecast to grow, while the Wine 4 unemployment rate will decrease. These factors are expected to boost the Canadian economy and benefit the C$36.8 billion alcoholic drink market. From 2011 to 2016, Canada’s economy Beer 8 is expected to continue growing with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2% and 3% (Euromonitor, 2012). Spirits 11 Canada’s provinces and territories vary significantly in geographic size and population, with Ontario being the largest 15 alcoholic beverages market in Canada. Provincial governments Distribution Channels determine the legal drinking age, which varies from 18 to 19 years of age, depending on the province or territory. Alcoholic New Product Launch 16 beverages must be distributed and sold through provincial liquor Analysis control boards, with some exceptions, such as in British Columbia (B.C.), Alberta and Quebec (AAFC, 2012). New Product Examples 17 Nationally, value sales of alcoholic drinks did well in 2011, with by Trend 4% growth, due to price increases and premium products such as wine, craft beer and certain types of spirits. -

Inniskillin Wines Fonds 1970-2014, N.D

Inniskillin Wines fonds 1970-2014, n.d. RG 489 Brock University Archives Creator: Inniskillin Wines Extent: 2.8 metres of textual records (10 boxes) 2327 photographs 721 slides 550 negatives 292 medals ca. 250 wine labels 163 VHS tapes 70 plaques 40 contact sheets 5 3D glass awards 3 compact disks 2 floppy disks 2 engraved stamps (dies) Abstract: Fonds contains material relating to the Inniskillin winery. Most of the materials are awards, news clippings, videos, photographs, product information and wine labels. Materials: Awards, news clippings, video cassettes, photographs, programs, promotional material, product information and wine labels. Repository: Brock University Archives Processed by: Chantal Cameron Finding aid: Chantal Cameron Last updated: April 2016 RG 489 Page 2 Terms of Use: Inniskillin fonds are open for research. Use restrictions: Current copyright applies. In some instances, researchers must obtain the written permission of the holder(s) of copyright and the Brock University Archives before publishing quotations from materials in the collection. Most papers may be copied in accordance with the Library’s usual procedures unless otherwise specified. Preferred Citation: RG 489, Inniskillin Wines fonds, 1970-2014. Brock University Archives, Brock University. Acquisition info.: Donated by Inniskillin Wines in 2013. Additional material was donated in 2015. Administrative History: Inniskillin Wines was founded by Karl Kaiser and Donald Ziraldo in 1975 in Niagara-on- the-Lake, Ontario. They had met the previous year, when Karl Kaiser, a winemaker and chemist, purchased some grapes from Donald Ziraldo, who owned and operated Ziraldo Nurseries. The two shared a vision of producing better quality Canadian wines and formed a partnership, with Kaiser making the wine and Ziraldo serving as company President. -

Canadian Blended Wine Industry and Labelling Overview January 2017 There Are Two Types of Wines Primarily Produced in Canada

Canadian Blended Wine Industry and Labelling Overview January 2017 There are two types of wines primarily produced in Canada: 100% Canadian (includes VQA and BC VQA) and International Canadian Blends. Together, they contribute an annual economic impact of $6.8 billion ($3.7B for 100% Canadian and $3.1B for blended wines). Blended wines are an important part of the Canadian wine industry, supporting over 10,000 jobs (direct and indirect) and purchasing more than 15,000 tonnes of Canadian grapes annually. International Canadian Blended (ICB) wines use the label “Cellared in Canada by (naming the company), (address) from imported and/or domestic wines” label designation must include domestic content to meet federal labelling requirements to ensure the label is not false, misleading or deceptive. Ontario regulations require that blended wines produced and sold in the province, contain a minimum 25% Ontario grape content. ICB wines are sold domestically to compete against imported wines in the value price category. For example, the LCBO reports that the average price of an ICB wine is $7.54, compared $13.25 for a VQA wine and $31.56 for a VQA wine in its specialty section, VINTAGES. Canada has a long history of blending domestic and imported wines. We are not unique, as blended wines are produced around the world, including major wine producing countries like Europe and the United States. Labelling of Wine in Canada Canada’s Food and Drug Act Regulations require wine labels to include “a clear indication of the country of origin,” while beer, spirits and all other food products can voluntarily indicate country of origin on the label. -

Ontario's Local Food Report

Ontario’s Local Food Report 2015/16 Edition Table of Contents Message from the Minister 4 2015/16 in Review 5 Funding Summary 5 Achievements 5 Why Local Food Matters 6 What We Want to Achieve 7 Increasing Awareness 9 Initiatives & Achievements 9 The Results 11 Success Stories 13 Increasing Access 15 Initiatives & Achievements 15 The Results 17 Success Stories 19 Increasing Supply and Sales 21 Initiatives & Achievements 21 The Results 25 Success Stories 27 The Future of Local Food 30 Message from the Minister Ontario is an agri-food powerhouse. Our farmers harvest an impressive abundance from our fields and farms, our orchards and our vineyards. And our numerous processors — whether they be bakers, butchers, or brewers — transform that bounty across the value chain into the highest-quality products for consumers. Together, they generate more than $35 billion in GDP and provide more than 781,000 jobs. That is why supporting the agri-food industry is a crucial component of the Ontario government’s four-part plan for building our province up. Ontario’s agri-food industry is the cornerstone of our province’s success, and the government recognizes not only its tremendous contributions today, but its potential for growth and success in the future. The 2013 Local Food Act takes that support further, providing the foundation for our Local Food Strategy to help increase demand for Ontario food here at home, create new jobs and enhance the economic contributions of the agri-food industry. Ontario’s Local Food Strategy outlines three main objectives: to enhance awareness of local food, to increase access to local food and to boost the supply of food produced in Ontario. -

Cabernet Franc VQA Niagara Peninsula 2017

inniskillin.com ICEWINE Cabernet Franc VQA Niagara Peninsula 2017 HARVEST After a spectacular warm and dry fall the weather turned sharply cold in November, bringing the first hard frost in the first week of the month and the first freeze/thaw event shortly thereafter allowing the grapes to begin developing all the classic Icewine characteristics. Ready for harvesting in the early morning of December 14 the Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Riesling and Vidal were harvested over the next few consecutive days, as temperatures were perfect falling between -9°C to -11°C. Thanks to this early harvest, the juice was of the highest quality, with plentiful yields and excellent concentration. WINEMAKING The grapes for this Cabernet Franc Icewine were harvested from select vineyards throughout the Niagara Peninsula at a frigid temperature of -10°C. Pressed immediately, the viscous juice was cold settled for 7 days before racking and inoculating. Fermented cool for approximately 21 days the resulting wine was filtered and transferred to a stainless steel tank to await bottling. WINEMAKER'S NOTES This concentrated and vibrant Icewine is bursting with juicy fruit aromatics of strawberry and cherry with hints of fresh cream. On the palate rich layers of strawberry, raspberry and rhubarb dominate with another hint of fresh vanilla cream. This luscious Icewine has a well-balanced acidity and long fruit filled finish. FOOD PAIRINGS Chocolate mousse Chocolate covered strawberries Blueberry pudding and chocolate sauce PRODUCT INFORMATION TECHNICAL ANALYSIS Size 375 mL Alcohol/Vol 9.45 % Winemaker Bruce Nicholson pH 3.27 Residual Sugar 244 g/l Total Acidity 9.15 g/l Oak Aging NO. -

2020 Canada Province-Level Wine Landscapes

WINE INTELLIGENCE CANADA PROVINCE-LEVEL WINE LANDSCAPES 2020 FEBRUARY 2020 1 Copyright © Wine Intelligence 2020 • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means) without the permission of the copyright owners. Application for permission should be addressed to Wine Intelligence. • The source of all information in this publication is Wine Intelligence unless otherwise stated. • Wine Intelligence shall not be liable for any damages (including without limitation, damages for loss of business or loss of profits) arising in contract, tort or otherwise from this publication or any information contained in it, or from any action or decision taken as a result of reading this publication. • Please refer to the Wine Intelligence Terms and Conditions for Syndicated Research Reports for details about the licensing of this report, and the use to which it can be put by licencees. • Wine Intelligence Ltd: 109 Maltings Place, 169 Tower Bridge Road, London SE1 3LJ Tel: 020 73781277. E-mail: [email protected]. Registered in England as a limited company number: 4375306 2 CONTENTS ▪ How to read this report p. 5 ▪ Management summary p. 7 ▪ Wine market provinces: key differences p. 21 ▪ Ontario p. 32 ▪ Alberta p. 42 ▪ British Colombia p. 52 ▪ Québec p. 62 ▪ Manitoba p. 72 ▪ Nova Scotia p. 82 ▪ Appendix p. 92 ▪ Methodology p. 100 3 CONTENTS ▪ How to read this report p. 5 ▪ Management summary p. 7 ▪ Wine market provinces: key differences p. 21 ▪ Ontario p. 32 ▪ Alberta p. 42 ▪ British Colombia p. 52 ▪ Québec p. -

Media Kit the Wines of British Columbia “Your Wines Are the Wines of Sensational!” British Columbia ~ Steven Spurrier

MEDIA KIT THE WINES OF BRITISH COLUMBIA “YOUR WINES ARE THE WINES OF SENSATIONAL!” BRITISH COLUMBIA ~ STEVEN SPURRIER British Columbia is a very special place for wine and, thanks to a handful of hard-working visionaries, our vibrant industry has been making a name for itself nationally and internationally for the past 25 years. “BC WINE OFTEN HAS In 1990, the Vintner’s Quality Alliance (VQA) standard was created to guarantee consumers they A RADICAL FRESHNESS were drinking wine made from 100% BC grown grapes. Today, BC VQA Wines dominate wine sales AND A REMARKABLE in British Columbia, and our wines are finding their way to more places than ever before, winning ABILITY TO DEFY over both critics and consumers internationally. THE CONVENTIONAL CATEGORIES OF TASTE.” The Wines of British Columbia truly are a reflection of the land where the grapes are grown and the exceptional people who craft them. We invite you to join us to savour all that makes the Wines of STUART PIGOTT British Columbia so special. ~ “WHAT I LOVE MOST ABOUT BC WINES IS THEY MIMIC THE PLACE, THEY MIMIC THE PURITY. YOU LOOK OUT AND FEEL THE AIR, TASTE THE WATER AND LOOK AT THE LAKE AND YOU CAN’T HELP BUT BE STRUCK BY A SENSE OF PURITY AND IT CARRIES OVER TO THE WINE. THEY HAVE PURITY AND A SENSE OF WEIGHTLESSNESS WHICH IS VERY ETHEREAL AND CAPTIVATING.” ~ KAREN MACNEIL DID YOU KNOW? • British Columbia’s Vintners Quality Alliance (BC VQA) designation celebrated 25 years of excellence in 2015. • BC’s Wine Industry has grown from just 17 grape wineries in 1990 to more than 275 today (as of January 2017). -

Inniskillin.Com

inniskillin.com DISCOVERY SERIES P3 VQA NIAGARA PENINSULA 2012 HARVEST The 2012 Harvest was spectacular. The hot, dry summer conditions delivered one of the best quality harvests for Ontario in years across all varietals. The summer conditions were reflected in what was our earliest start on record, with grapes being processed for the first time in August, and in turn, having all varieties in house before November. The ideal weather conditions delivered fully ripening fruit. The aromatic whites, Riesling and Pinot Grigio, are more varietal specific while the fruit definition for Chardonnay and Pinot Noir are simply stunning. The depth of colour and intensity of flavors are strong on the late ripening Merlot, Cabernets and Shiraz, which flourished in the hot, dry conditions. WINEMAKING These 3 Pinot varieties were picked from select vineyards throughout the Niagara Peninsula. The Pinot Noir and Pinot Blanc were fermented separately in stainless steel while the Pinot Grigio was fermented and aged in French Oak for three months for added complexity. To make the final blend the wines were then put together at a ratio of 49% Pinot Noir, 35% Pinot Grigio and 16% Pinot Blanc. WINEMAKER’S NOTES This unique blend provides citrus notes of lemon and lime, along with floral notes and a touch of vanilla. The palate shows flavours of green apple and peach balanced by a crisp, refreshing acidity. FOOD PAIRINGS Great sipping and reception wine! Delicate summer salads such as baby spinach and strawberries; watermelon and cucumber with feta; fresh angel hair pasta with olive oil or crispy vegetable spring rolls. -

Connecting Wine with Tourism – Inniskillin Has Been the 'Ice Breaker

Connecting Wine with Tourism – Inniskillin has been the ‘Ice Breaker’. Inniskillin is one of the Canadian wine industry’s original pioneers, producing distinctive estate wines that rank among the world’s finest. But it is Inniskillin’s constant dedication to innovation that recognises it as being one of the best among its peers and it has become a leader in wider industry focus on education and research. Inniskillin was established in 1975 and has become famous for its Icewine due to its unique microclimate on the Niagara Peninsula, only twenty minutes from the famous Niagara Falls. The 1980s saw Ontario take its place at the table of the world’s cool climate wine regions. The 1990s saw to create a Canadian character. Ziraldo believes this is it finesse its style, identify its most privileged sites and one of the major brand images for Inniskillin and planned build its reputation beyond regional interest into the future expansion and renovation (which will include a wine mainstream of the world’s acknowledged fine wines. The education centre focusing on the Icewine Experience) will evolution of wines in Canada has been nothing short of be in keeping with this style of architecture. phenomenal. Inniskillin Icewine is a global brand that is positioned as the luxury wine from Canada taking The philosophy has always been about connecting wine advantage of the strong association between Canada, ice with tourism as Ziraldo believes ‘it’s not what you say and snow. Red wine development has accelerated rapidly about yourself, but letting others have their say about and Pinot Noir is finding a very quality-focused niche in you’. -

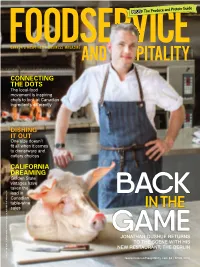

Connecting the Dots

CONNECTING THE DOTS The local-food movement is inspiring chefs to look at Canadian ingredients differently DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit all when it comes to dinnerware and cutlery choices CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden State vintages have taken the lead in Canadian table-wine sales JONATHAN GUSHUE RETURNS TO THE SCENE WITH HIS NEW RESTAURANT, THE BERLIN CANADIAN PUBLICATION MAIL PRODUCT SALES AGREEMENT #40063470 CANADIAN PUBLICATION foodserviceandhospitality.com $4 | APRIL 2016 VOLUME 49, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2016 CONTENTS 40 27 14 Features 11 FACE TIME Whether it’s eco-proteins 14 CONNECTING THE DOTS The 35 CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden or smart technology, the NRA Show local-food movement is inspiring State vintages have taken the lead aims to connect operators on a chefs to look at Canadian in Canadian table-wine sales host of industry issues ingredients differently By Danielle Schalk By Jackie Sloat-Spencer By Andrew Coppolino 37 DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit 22 BACK IN THE GAME After vanish - all when it comes to dinnerware and ing from the restaurant scene in cutlery choices By Denise Deveau 2012, Jonathan Gushue is back CUE] in the spotlight with his new c restaurant, The Berlin DEPARTMENTS By Andrew Coppolino 27 THE SUSTAINABILITY PARADIGM 2 FROM THE EDITOR While the day-to-day business of 5 FYI running a sustainable food operation 12 FROM THE DESK is challenging, it is becoming the new OF ROBERT CARTER normal By Cinda Chavich 40 CHEF’S CORNER: Neil McCue, Whitehall, Calgary PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY [NEIL M OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE FOODSERVICEANDHOSPITALITY.COM FOODSERVICE AND HOSPITALITY APRIL 2016 1 FROM THE EDITOR For daily news and announcements: @foodservicemag on Twitter and Foodservice and Hospitality on Facebook.