Documenting Hip-Hop Sampling As Critical Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigating Hip-Hop's Emergence in the Spaces of Late Capitalism

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2008 Re-Taking it to the Streets: Investigating Hip-Hop's Emergence in the Spaces of Late Capitalism Kevin Waide Kosanovich College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kosanovich, Kevin Waide, "Re-Taking it to the Streets: Investigating Hip-Hop's Emergence in the Spaces of Late Capitalism" (2008). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626547. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-zyvx-b686 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Re-Taking it to the Streets: Investigating Hip-Hop’s Emergence in the Spaces of Late Capitalism Kevin Waide Kosanovich Saginaw, Michigan Bachelor of Arts, University of Michigan, 2003 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August, 2008 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts aide KosanovichKej Approved,by the Committee, May, 2008 imittee Chair Associate Pro rn, The College of William & Mary Associate Professor A lege of William & Mary Assistant P ressor John Gamber, The College of William & Mary ABSTRACT PAGE Much of the scholarship focusing on rap and hip-hop argues that these cultural forms represent instances of African American cultural resistance. -

Williams, Justin A. (2010) Musical Borrowing in Hip-Hop Music: Theoretical Frameworks and Case Studies

Williams, Justin A. (2010) Musical borrowing in hip-hop music: theoretical frameworks and case studies. PhD thesis, University of Nottingham. Access from the University of Nottingham repository: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/11081/1/JustinWilliams_PhDfinal.pdf Copyright and reuse: The Nottingham ePrints service makes this work by researchers of the University of Nottingham available open access under the following conditions. · Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. · To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in Nottingham ePrints has been checked for eligibility before being made available. · Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not- for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. · Quotations or similar reproductions must be sufficiently acknowledged. Please see our full end user licence at: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/end_user_agreement.pdf A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the repository url above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information, please contact [email protected] MUSICAL BORROWING IN HIP-HOP MUSIC: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS AND CASE STUDIES Justin A. -

Westminsterresearch Synth Sonics As

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Synth Sonics as Stylistic Signifiers in Sample-Based Hip-Hop: Synthetic Aesthetics from ‘Old-Skool’ to Trap Exarchos, M. This is an electronic version of a paper presented at the 2nd Annual Synthposium, Melbourne, Australia, 14 November 2016. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 2nd Annual Synthposium Synthesisers: Meaning though Sonics Synth Sonics as Stylistic Signifiers in Sample-Based Hip-Hop: Synthetic Aesthetics from ‘Old-School’ to Trap Michail Exarchos (a.k.a. Stereo Mike), London College of Music, University of West London Intro-thesis The literature on synthesisers ranges from textbooks on usage and historiogra- phy1 to scholarly analysis of their technological development under musicological and sociotechnical perspectives2. Most of these approaches, in one form or another, ac- knowledge the impact of synthesisers on musical culture, either by celebrating their role in powering avant-garde eras of sonic experimentation and composition, or by mapping the relationship between manufacturing trends and stylistic divergences in popular mu- sic. The availability of affordable, portable and approachable synthesiser designs has been highlighted as a catalyst for their crossover from academic to popular spheres, while a number of authors have dealt with the transition from analogue to digital tech- nologies and their effect on the stylisation of performance and production approaches3. -

A History of Hip Hop in Halifax: 1985 - 1998

HOW THE EAST COAST ROCKS: A HISTORY OF HIP HOP IN HALIFAX: 1985 - 1998 by Michael McGuire Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2011 © Copyright by Michael McGuire, 2011 DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY The undersigned hereby certify that they have read and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies for acceptance a thesis entitled “HOW THE EAST COAST ROCKS: A HISTORY OF HIP HOP IN HALIFAX: 1985 - 1998” by Michael McGuire in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Dated: August 18, 2011 Supervisor: _________________________________ Readers: _________________________________ _________________________________ ii DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY DATE: August 18, 2011 AUTHOR: Michael McGuire TITLE: How the East Coast Rocks: A History Of Hip Hop In Halifax: 1985 - 1998 DEPARTMENT OR SCHOOL: Department of History DEGREE: MA CONVOCATION: October YEAR: 2011 Permission is herewith granted to Dalhousie University to circulate and to have copied for non-commercial purposes, at its discretion, the above title upon the request of individuals or institutions. I understand that my thesis will be electronically available to the public. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the thesis nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author’s written permission. The author attests that permission has been obtained for the use of any copyrighted material appearing in the -

BOONE-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Copyright by Christine Emily Boone 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Christine Emily Boone Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics Committee: James Buhler, Supervisor Byron Almén Eric Drott Andrew Dell‘Antonio John Weinstock Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics by Christine Emily Boone, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Acknowledgements I want to first acknowledge those people who had a direct influence on the creation of this document. My brother, Philip, introduced me mashups a few years ago, and spawned my interest in the subject. Dr. Eric Drott taught a seminar on analyzing popular music where I was first able to research and write about mashups. And of course, my advisor, Dr. Jim Buhler has given me immeasurable help and guidance as I worked to complete both my degree and my dissertation. Thank you all so much for your help with this project. Although I am the only author of this dissertation, it truly could not have been completed without the help of many more people. First I would like to thank all of my professors, colleagues, and students at the University of Texas for making my time here so productive. I feel incredibly prepared to enter the field as an educator and a scholar thanks to all of you. I also want to thank all of my friends here in Austin and in other cities. -

Theoretical Approaches to Quotation in Hip-Hop Recordings Justin A

Williams, J. A. (2014). Theoretical Approaches to Quotation in Hip- Hop Recordings. Contemporary Music Review, 33(2), 188-209. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2014.959276 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to published version (if available): 10.1080/07494467.2014.959276 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ This article was downloaded by: [University of Bristol] On: 26 March 2015, At: 13:07 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Contemporary Music Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gcmr20 Theoretical Approaches to Quotation in Hip-Hop Recordings Justin A. Williams Published online: 28 Oct 2014. Click for updates To cite this article: Justin A. Williams (2014) Theoretical Approaches to Quotation in Hip-Hop Recordings, Contemporary Music Review, 33:2, 188-209, DOI: 10.1080/07494467.2014.959276 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2014.959276 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. -

Hip-Hop Is My Passport! Using Hip-Hop and Digital Literacies to Understand Global Citizenship Education

HIP-HOP IS MY PASSPORT! USING HIP-HOP AND DIGITAL LITERACIES TO UNDERSTAND GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP EDUCATION By Akesha Monique Horton A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Curriculum, Teaching and Educational Policy – Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT HIP-HOP IS MY PASSPORT! USING HIP-HOP AND DIGITAL LITERACIES TO UNDERSTAND GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP EDUCATION By Akesha Monique Horton Hip-hop has exploded around the world among youth. It is not simply an American source of entertainment; it is a global cultural movement that provides a voice for youth worldwide who have not been able to express their “cultural world” through mainstream media. The emerging field of critical hip-hop pedagogy has produced little empirical research on how youth understand global citizenship. In this increasingly globalized world, this gap in the research is a serious lacuna. My research examines the intersection of hip-hop, global citizenship education and digital literacies in an effort to increase our understanding of how urban youth from two very different urban areas, (Detroit, Michigan, United States and Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) make sense of and construct identities as global citizens. This study is based on the view that engaging urban and marginalized youth with hip-hop and digital literacies is a way to help them develop the practices of critical global citizenship. Using principled assemblage of qualitative methods, I analyze interviews and classroom observations - as well as digital artifacts produced in workshops - to determine how youth define global citizenship, and how socially conscious, global hip-hop contributes to their definition Copyright by AKESHA MONIQUE HORTON 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely grateful for the wisdom and diligence of my dissertation committee: Michigan State University Drs. -

0 Musical Borrowing in Hip-Hop

MUSICAL BORROWING IN HIP-HOP MUSIC: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS AND CASE STUDIES Justin A. Williams, BA, MMus Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2009 0 Musical Borrowing in Hip-hop Music: Theoretical Frameworks and Case Studies Justin A. Williams ABSTRACT ‗Musical Borrowing in Hip-hop‘ begins with a crucial premise: the hip-hop world, as an imagined community, regards unconcealed intertextuality as integral to the production and reception of its artistic culture. In other words, borrowing, in its multidimensional forms and manifestations, is central to the aesthetics of hip-hop. This study of borrowing in hip-hop music, which transcends narrow discourses on ‗sampling‘ (digital sampling), illustrates the variety of ways that one can borrow from a source text or trope, and ways that audiences identify and respond to these practices. Another function of this thesis is to initiate a more nuanced discourse in hip-hop studies, to allow for the number of intertextual avenues travelled within hip-hop recordings, and to present academic frameworks with which to study them. The following five chapters provide case studies that prove that musical borrowing, part and parcel of hip-hop aesthetics, occurs on multiple planes and within myriad dimensions. These case studies include borrowing from the internal past of the genre (Ch. 1), the use of jazz and its reception as an ‗art music‘ within hip-hop (Ch. 2), borrowing and mixing intended for listening spaces such as the automobile (Ch. 3), sampling the voice of rap artists posthumously (Ch. 4), and sampling and borrowing as lineage within the gangsta rap subgenre (Ch. -

'You Never Been on a Ride Like This Befo'

[PMH 4.2 (2010) 160-176] Popular Music History (print) ISSN 1740-7133 doi:10.1558/pomh.v4i2.160 Popular Music History (online) ISSN 1743-1646 Justin A. Williams ‘You never been on a ride like this befo’: Los Angeles, automotive listening, and Dr. Dre’s ‘G-Funk’* Justin Williams is currently a Principal Lecturer in Department of Music and Popular Music at Anglia Ruskin University. He recently Performing Arts completed an ESRC-funded Postdoctoral Fellowship Anglia Ruskin University to research a project on music and automobility at the East Road Centre for Mobilities Research at Lancaster University. Cambridge CB1 1PT He is currently under contract from University of Mich- [email protected] igan Press to write a book on musical borrowing and intertextuality in hip-hop music. Abstract Since the 1920s, multiple historically specific factors led to the automobile-saturated environ- ment of Los Angeles, contributing to a car-dependent lifestyle for most of its inhabitants. With car travel as its primary mode of mobility, and as a hub of numerous cultural industries through- out the twentieth century, the city has been the breeding ground for a number of car cultures, including hot rods, custom cars, and lowriders in addition to the large output of films and music recordings produced. In rap music of the early 1990s, producer/rapper Dr. Dre’s (Andre Romelle Young) creation of a style labelled ‘G-funk’, according to him, was created and mixed specifically for listening in car stereo systems. This article provides one case study of music’s intersections with geography, both the influence of urban geography on music production and the geogra- phy of particular listening spaces. -

Abstract Humanities Jordan Iii, Augustus W. B.S. Florida

ABSTRACT HUMANITIES JORDAN III, AUGUSTUS W. B.S. FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY, 1994 M.A. CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY, 1998 THE IDEOLOGICAL AND NARRATIVE STRUCTURES OF HIP-HOP MUSIC: A STUDY OF SELECTED HIP-HOP ARTISTS Advisor: Dr. Viktor Osinubi Dissertation Dated May 2009 This study examined the discourse of selected Hip-Hop artists and the biographical aspects of the works. The study was based on the structuralist theory of Roland Barthes which claims that many times a performer’s life experiences with class struggle are directly reflected in his artistic works. Since rap music is a counter-culture invention which was started by minorities in the South Bronx borough ofNew York over dissatisfaction with their community, it is a cultural phenomenon that fits into the category of economic and political class struggle. The study recorded and interpreted the lyrics of New York artists Shawn Carter (Jay Z), Nasir Jones (Nas), and southern artists Clifford Harris II (T.I.) and Wesley Weston (Lii’ Flip). The artists were selected on the basis of geographical spread and diversity. Although Hip-Hop was again founded in New York City, it has now spread to other parts of the United States and worldwide. The study investigated the biography of the artists to illuminate their struggles with poverty, family dysfunction, aggression, and intimidation. 1 The artists were found to engage in lyrical battles; therefore, their competitive discourses were analyzed in specific Hip-Hop selections to investigate their claims of authorship, imitation, and authenticity, including their use of sexual discourse and artistic rivalry, to gain competitive advantage. -

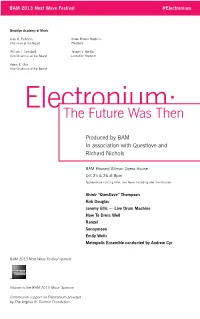

Electronium:The Future Was Then

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #Electronium Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Karen Brooks Hopkins, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Electronium:The Future Was Then Produced by BAM In association with Questlove and Richard Nichols BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Oct 25 & 26 at 8pm Approximate running time: two hours including one intermission Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson Kirk Douglas Jeremy Ellis — Live Drum Machine How To Dress Well Rahzel Sonnymoon Emily Wells Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Commission support for Electronium provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Electronium Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr: Kristin Lee, violin (concertmaster) Francisco Fullana, violin Karen Kim, viola Hiro Matsuo, cello Mellissa Hughes, soprano Virginia Warnken, alto Geoffrey Silver, tenor Jonathan Woody, bass-baritone ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Arrangements by Daniel Felsenfeld, DD Jackson, Patrick McMinn and Anthony Tid Lighting design by Albin Sardzinski Sound engineering by John Smeltz Stage design by Alex Delaunay Stage manager Cheng-Yu Wei Electronium references the first electronic synthesizer created exclusively for the composition and performance of music. Initially created for Motown by composer-technologist Raymond Scott, the electronium was designed but never released for distribution; the one remaining machine is undergoing restoration. Complemented by interactive lighting and aural mash-ups, the music of Electronium: The Future Was Then honors the legacy of the electronium in a production that celebrates both digital and live music interplay. -

Perspectives on the Evolution of Hip-Hop Music Through Themes of Race, Crime, and Violence Kelsey B

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Honors Theses Student Scholarship Fall 2015 Perspectives on the Evolution of Hip-Hop Music through Themes of Race, Crime, and Violence Kelsey B. Basham Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Basham, Kelsey B., "Perspectives on the Evolution of Hip-Hop Music through Themes of Race, Crime, and Violence" (2015). Honors Theses. 270. https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses/270 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: PERSPECTIVES ON THE EVOLUTION OF HIP-HOP MUSIC Eastern Kentucky University Perspectives on the Evolution of Hip-Hop Music through Themes of Race, Crime, and Violence Honors Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment Of The Requirements of HON 420 Fall 2015 By Kelsey B. Basham Faculty Mentor Dr. Ken Tunnell Department of Criminal Justice & Police Studies PERSPECTIVES ON THE EVOLUTION OF HIP-HOP MUSIC i Perspectives on the Evolution of Hip-Hop Music through Themes of Race, Crime, and Violence Kelsey Basham Dr. Ken Tunnell, Department of Criminal Justice & Police Studies This thesis examines the role or race, crime, and violence as major themes in hip-hop music through existing academic literature. Utilizing the three major themes, this paper discusses the inherent ties of race, crime, and violence to the production of hip-hop music which can reflect broader social issues existing in American society over the time period from 1970-present day.