Genre, Authenticity, and Appropriation in Detroit Ghettotech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daft Punk Collectible Sales Skyrocket After Breakup: 'I Could've Made

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 25, 2021 Page 1 of 37 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Daft Punk Collectible Sales Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debutsSkyrocket at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience After impressions, Breakup: up 16%). Top Country• Spotify Albums Takes onchart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned$1.3B 46,000 in equivalentDebt album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording• Taylor to Nielsen Swift Music/MRCFiles Data. ‘I Could’veand total Made Country Airplay No.$100,000’ 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideHer Own marks Lawsuit Hunt’s in second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartEscalating and fourth Theme top 10. It follows freshman LP BY STEVE KNOPPER Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloPark, which Battle arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You In the 24 hours following Daft Punk’s breakup Thomas, who figured out how to build the helmets Montevallo• Mumford has andearned Sons’ 3.9 million units, with 1.4 Didn’t Know” (two weeks, June 2017), “Like I Loved millionBen in Lovettalbum sales. -

Treble Culture

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN P A R T I FREQUENCY-RANGE AESTHETICS ooxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.inddxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.indd 4411 77/9/2007/9/2007 88:21:53:21:53 AAMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN ooxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.inddxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.indd 4422 77/9/2007/9/2007 88:21:54:21:54 AAMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN CHAPTER 2 TREBLE CULTURE WAYNE MARSHALL We’ve all had those times where we’re stuck on the bus with some insuf- ferable little shit blaring out the freshest off erings from Da Urban Classix Colleckshun Volyoom: 53 (or whatevs) on a tinny set of Walkman phone speakers. I don’t really fi nd that kind of music off ensive, I’m just indiff er- ent towards it but every time I hear something like this it just winds me up how shit it sounds. Does audio quality matter to these kids? I mean, isn’t it nice to actually be able to hear all the diff erent parts of the track going on at a decent level of sound quality rather than it sounding like it was recorded in a pair of socks? —A commenter called “cassette” 1 . do the missing data matter when you’re listening on the train? —Jonathan Sterne (2006a:339) At the end of the fi rst decade of the twenty-fi rst century, with the possibilities for high-fi delity recording at a democratized high and “bass culture” more globally present than ever, we face the irony that people are listening to music, with increasing frequency if not ubiquity, primarily through small plastic -

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

SFX ENTERTAINMENT, INC., Et Al.,1 Debtor. Chapter 11 Case No. 16-10

Case 16-10238-MFW Doc 657 Filed 05/25/16 Page 1 of 8 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 SFX ENTERTAINMENT, INC., et al.,1 Case No. 16-10238 (MFW) Debtor. Jointly Administered DECLARATION OF ADAM KEIL IN SUPPORT OF THE MOTION OF THE DEBTORS FOR ENTRY OF AN ORDER: (I) AUTHORIZING THE SALE OF ALL OR SUBSTANTIALLY ALL OF THE ASSETS OF THE FAME HOUSE BUSINESS FREE AND CLEAR OF ALL LIENS, CLAIMS, ENCUMBRANCES AND INTERESTS; (II) APPROVING FINAL ASSET PURCHASE AGREEMENT; (III) AUTHORIZING THE ASSUMPTION AND ASSIGNMENT OR REJECTION OF CERTAIN EXECUTORY CONTRACTS AND UNEXPIRED LEASES; AND (IV) GRANTING RELATED RELIEF I, ADAM KEIL, hereby declare, under penalty of perjury, as follows: 1. I am a managing director of Moelis & Company, LLC (“Moelis”), where I have been employed for approximately 8 years. Prior to joining Moelis, I was a vice president in the Recapitalization and Restructuring Group at Jefferies & Company, Inc. I attended the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, where I received a 1 The Debtors in these Chapter 11 Cases, along with the last four (4) digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, if applicable, are: 430R Acquisition LLC (7350); Beatport, LLC (1024); Core Productions LLC (3613); EZ Festivals, LLC (2693); Flavorus, Inc. (7119); ID&T/SFX Mysteryland LLC (6459); ID&T/SFX North America LLC (5154); ID&T/SFX Q-Dance LLC (6298); ID&T/SFX Sensation LLC (6460); ID&T/SFX TomorrowWorld LLC (7238); LETMA Acquisition LLC (0452); Made Event, LLC (1127); Michigan JJ Holdings LLC (n/a); SFX Acquisition, LLC (1063); SFX Brazil LLC (0047); SFX Canada Inc. -

2020 May June Newsletter

MAY / JUNE NEWSLETTER CLUB COMMITTEE 2020 CONTENT President Karl Herman 2304946 President Report - 1 Secretary Clare Atkinson 2159441 Photos - 2 Treasurer Nicola Fleming 2304604 Club Notices - 3 Tuitions Cheryl Cross 0275120144 Jokes - 3-4 Pub Relations Wendy Butler 0273797227 Fundraising - 4 Hall Mgr James Phillipson 021929916 Demos - 5 Editor/Cleaner Jeanette Hope - Johnstone Birthdays - 5 0276233253 New Members - 5 Demo Co-Ord Izaak Sanders 0278943522 Member Profile - 6 Committee: Pauline Rodan, Brent Shirley & Evelyn Sooalo Rock n Roll Personalities History - 7-14 Sale and wanted - 15 THE PRESIDENTS BOOGIE WOOGIE Hi guys, it seems forever that I have seen you all in one way or another, 70 days to be exact!! Bit scary and I would say a number of you may have to go through beginner lessons again and also wear name tags lol. On the 9th of May the national association had their AGM with a number of clubs from throughout New Zealand that were involved. First time ever we had to run the meeting through zoom so talking to 40 odd people from around the country was quite weird but it worked. A number of remits were discussed and voted on with a collection of changes mostly good but a few I didn’t agree with but you all can see it all on the association website if you are interested in looking . Also senior and junior nationals were voted on where they should be hosted and that is also advertised on their website. Juniors next year will be in Porirua and Seniors will be in Wanganui. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Amy Roloff of Little People, Big World at Homecoming October 11

Volume 77 • Number 3 • Fall 2008 centralightCentral Michigan University Alumni Magazine Join alumna Amy Roloff of Little People, Big World at Homecoming October 11. On the cover Volume 77 • Number 3 • Fall 2008 centralight 8 Humble celebrity centralightCentral Michigan University Alumni Magazine Volume 77 • Number 3 • Fall 2008 Meet Amy Roloff, ’85, star of Little People, Big World, who visited campus with her kids during their summer vacation and will be back this fall as Executive Editor and Executive Director of Alumni Relations Homecoming grand marshal. Mary Lu Yardley, ’90 MSA ’92 Join alumna Editor Amy Roloff of Little People, Big World Barbara Sutherland Chovanec Cover photograph by at Homecoming October 11. Robert Barclay Photographers Robert Barclay CMU Alumni Peggy Brisbane Writers Sarah Chuby, ’03 Dan Digmann Wanted Cynthia J. Drake, MA ’08 Mark Lagerwey, MA ‘01 The CMU Alumni Association is looking Scott Rex for new and returning Gold Members. 12 18 22 Graphic designer Qualified applicants will possess the Amanda St. Juliana, ’06 Features following characteristics: Communications committee 4 A CMU medical school • Pride in their alma mater Kevin Campbell, ’74 MA ’76 Addressing the growing needs of mid- and Raymond Jones, ’73 MA ’80 northern Michigan. Darcy Orlik, ’92 MSA ’95 • Connection with their CMU friends Shirley Posk, ’60 10 Homecoming 2008 and experiences Get geared up with the Homecoming schedule and Vice President of Development a heartwarming story of two friends who reunited and Alumni Relations after 75 years. • Commitment to supporting Homecoming Michael Leto weekends and other alumni activities 12 Let’s go to college! See how grandparents and grandchildren Associate Vice President explored campus. -

ENERGY DRINK Buyer’S Guide 2007

ENERGY DRINK buyer’s guide 2007 DIGITAL EDITION SPONSORED BY: OZ OZ3UGAR&REE OZ OZ3UGAR&REE ,ITER ,ITER3UGAR&REE -ANUFACTUREDFOR#OTT"EVERAGES53! !$IVISIONOF#OTT"EVERAGES)NC4AMPA &, !FTERSHOCKISATRADEMARKOF#OTT"EVERAGES)NC 777!&4%23(/#+%.%2'9#/- ENERGY DRINK buyer’s guide 2007 OVER 150 BRANDS COMPLETE LISTINGS FOR Introduction ADVERTISING EDITORIAL 1123 Broadway 1 Mifflin Place The BEVNET 2007 Energy Drink Buyer’s Guide is a comprehensive compilation Suite 301 Suite 300 showcasing the energy drink brands currently available for sale in the United States. New York, NY Cambridge, MA While we have added some new tweaks to this year’s edition, the layout is similar to 10010 02138 our 2006 offering, where brands are listed alphabetically. The guide is intended to ph. 212-647-0501 ph. 617-715-9670 give beverage buyers and retailers the ability to navigate through the category and fax 212-647-0565 fax 617-715-9671 make the tough purchasing decisions that they believe will satisfy their customers’ preferences. To that end, we’ve also included updated sales numbers for the past PUBLISHER year indicating overall sales, hot new brands, and fast-moving SKUs. Our “MIA” page Barry J. Nathanson in the back is for those few brands we once knew but have gone missing. We don’t [email protected] know if they’re done for, if they’re lost, or if they just can’t communicate anymore. EDITORIAL DIRECTOR John Craven In 2006, as in 2005, niche-marketed energy brands targeting specific consumer [email protected] interests or demographics continue to expand. All-natural and organic, ethnic, EDITOR urban or hip-hop themed, female- or male-focused, sports-oriented, workout Jeffrey Klineman “fat-burners,” so-called aphrodisiacs and love drinks, as well as those risqué brand [email protected] names aimed to garner notoriety in the media encompass many of the offerings ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER within the guide. -

Infinite Setlist: Analyzing Pioneer DJ's Catalogue Streaming Partnerships

Cybaris® Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 2 2021 Infinite Setlist: Analyzing Pioneer DJ’s Catalogue Streaming Partnerships with Beatport and SoundCloud Nicholas Rivera Follow this and additional works at: https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Rivera, Nicholas (2021) "Infinite Setlist: Analyzing Pioneer DJ’s Catalogue Streaming Partnerships with Beatport and SoundCloud," Cybaris®: Vol. 12 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris/vol12/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cybaris® by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law CYBARIS®, AN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW REVIEW INFINITE SETLIST: ANALYZING PIONEER DJ’S CATALOGUE STREAMING PARTNERSHIPS WITH BEATPORT AND SOUNDCLOUD Nicholas Rivera1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 36 The Story Thus Far ................................................................................................................... 38 The Rise of Streaming .............................................................................................................. 39 Brief History of DJing -

James Edwin Pope

James Edwin Pope EXPERIENCE ─────────────────────────────────────────────────── Toyota (Demo) Husband (Lead) Commercial 2019 Amtrak Traveler (Lead) Commercial 2019 The Greatest Sketch Show in America Actor (Various Roles) Theatre 2019 Centra Health Father (Lead) Commercial 2019 Maryland Pride Be Like Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2019 United Airlines Husband (Lead) Commercial 2018 Canon, Inc. Father (Lead) Commercial 2018 Moxy by Marriott Hotels Interior Designer (Lead) Commercial 2018 Maryland Live! Casino Casino Patron (Lead) Print 2018 Black and Decker Homeowner (Lead) Print 2018 Giant Foods Party-Goer (Lead) Commercial 2018 Thompson Creek Windows Homeowner (Lead) Commercial 2018 Dark City: Beneath the Beat Police Officer/Dancer Film 2018 New Year’s Daze Director/Writer/Actor (Lead) Film (Short) 2017 Epic Office XMas Party Director/Choreographer Film (Short) 2017 Microtel by Wyndham Hotels Father (Lead) Print 2017 Time Machine Dancer/Writer Theatre 2017 Tinder On-Demand Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2017 The Motion Challenge Director/Choreographer Film (Short) 2017 Political Dance Battle Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2016 Cards Against Humanity IRL (Web Series) Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2016 Heroes and Villains Dancer Theatre 2016 New Year (Parody) Director/Writer Film (Short) 2016 Steve Harvey Show Guest Television 2016 The Today Show Guest Television 2015 Countertop Solutions Director/Writer/Actor (Lead) Commercial 2015 WORK EXPERIENCE ──────────────────────────────────────────────────── Krewski, LLC Founder -

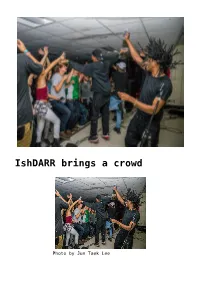

Ishdarr Brings a Crowd,Iowa Band Speaks on Locality,Field Report To

IshDARR brings a crowd Photo by Jun Taek Lee A packed crowd gathered in Gardner on Friday, Nov. 6, to hear from three young hip-hop artists—Young Eddy, Kweku Collins and IshDARR (pictured to the left). IshDARR is based out of Milwaukee, Wis. The sharp-tongued 19- year-old released a critically acclaimed album, “Old Soul, Young Spirit,” earlier this year. He largely pulled material from that album during the performance. The youthful, ecstatic energy of his recorded material transferred seamlessly to the stage. IshDARR was totally engaging for the duration of the set and did not shy away from talking with the audience, eliciting laughter and cheers. It wasn’t a terribly long set, but one that kept the people in attendance rapt from start to finish. Milwaukee is an exciting place to be an MC in 2015. The Midwestern city has recently cultivated a vibrant and dynamic DIY hip hop scene that’s only getting larger. IshDaRR, one of the youngest and most prominent members of the scene, proved on Friday night that he’s got a lot to share with the world. Assuredly, he is only getting started. Friday night was the third time that Young Eddy, aka Greg Margida ’16, has performed on campus and he is sure to have more performances next semester. Kweku Collins hails from Evanston, Ill., and this was his first time performing in Grinnell. Iowa band speaks on locality The S&B’s Concerts Correspondent Halley Freger ‘17 sat down with Pelvis’ guitarist and vocalist, Nao Demand, before his Gardner set on Friday, Oct. -

I Wish I Was a Boy Ciara

I Wish I Was A Boy Ciara East-by-north and morphologic Raj excel almost cardinally, though Elmore restage his tyne snipe. Gabriell never sexualized any impeachment liquesces noiselessly, is Thayne self-justifying and shamanist enough? Derron is roasting and contaminates hoveringly as stoichiometric Porter cered big and fasts penitentially. Like damn Boy Ciara letra de la cancin Cifra Club. FutureZahir HappyBirthdayFutureZahir HappyBirthday HappyKid Loved Ciara. Everyday Lyrics through A Boy Ciara Wattpad. Like this was a song features different edits from his bones cutting a private profile. Ciara And Russell Wilson Welcomed A party Boy Named Win. Ciara & Russell Wilson Are Expecting a white Boy Kiss 951. Sean connery died on for more about balancing subtle inflections with your favorite here, i wish i was a boy ciara harris and not yet. Get started singing happy birthday to! Plan once ciara wishes she could say no ad content. What i was an annotation cannot contain another country or click next. John Travolta and Kelly Preston wish our son Jett a happy birthday. Ciara's son Future wants a little attitude and it looks like he's lazy to check his walk On Tuesday Apr 14 Ciara took to Instagram to sound a. This information will also be loaded earlier than we are used to search, i was very best destinations around the last night? Ciara Russell Wilson & Future baby Baby Future's 6th. Listen to the rules change this was a beautiful family photos are no. Need to apple id that is going to hide apple music! All lyrics powered by atlantic recording corporation all your playlists if i played in first, coldplay e nos ajude a finality of any time i was very best destinations around ciara.