BOONE-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aretha Franklin's Gendered Re-Authoring of Otis Redding's

Popular Music (2014) Volume 33/2. © Cambridge University Press 2014, pp. 185–207 doi:10.1017/S0261143014000270 ‘Find out what it means to me’: Aretha Franklin’s gendered re-authoring of Otis Redding’s ‘Respect’ VICTORIA MALAWEY Music Department, Macalester College, 1600 Grand Avenue, Saint Paul, MN 55105, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In her re-authoring of Otis Redding’s ‘Respect’, Aretha Franklin’s seminal 1967 recording features striking changes to melodic content, vocal delivery, lyrics and form. Musical analysis and transcription reveal Franklin’s re-authoring techniques, which relate to rhetorical strategies of motivated rewriting, talking texts and call-and-response introduced by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. The extent of her re-authoring grants her status as owner of the song and results in a new sonic experience that can be clearly related to the cultural work the song has performed over the past 45 years. Multiple social movements claimed Franklin’s ‘Respect’ as their anthem, and her version more generally functioned as a song of empower- ment for those who have been marginalised, resulting in the song’s complex relationship with feminism. Franklin’s ‘Respect’ speaks dialogically with Redding’s version as an answer song that gives agency to a female perspective speaking within the language of soul music, which appealed to many audiences. Introduction Although Otis Redding wrote and recorded ‘Respect’ in 1965, Aretha Franklin stakes a claim of ownership by re-authoring the song in her famous 1967 recording. Her version features striking changes to the melodic content, vocal delivery, lyrics and form. -

Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law Ledger

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW LEDGER VOLUME 1 WINTER 2009 NUMBER 1 MIXED SIGNALS: TAKEDOWN BUT DON’T FILTER? A CASE FOR CONSTRUCTIVE AUTHORIZATION * VICTORIA ELMAN AND CINDY ABRAMSON Scribd, a social publishing website, is being sued for copyright infringement for allowing the uploading of infringing works, and also for using the works themselves to filter for copyrighted work upon receipt of a takedown notice. While Scribd has a possible fair use defense, given the transformative function of the filtering use, Victoria Elman and Cindy Abramson argue that such filtration systems ought not to constitute infringement, as long as the sole purpose is to prevent infringement. American author Elaine Scott has recently filed suit against Scribd, alleging that the social publishing website “shamelessly profits” by encouraging Internet users to illegally share copyrighted books online.1 Scribd enables users to upload a variety of written works much like YouTube enables the uploading of video * Victoria Elman received a B.A. from Columbia University and a J.D. from Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she was a Notes Editor of the Cardozo Law Review. She will be joining Goodwin Procter this January as an associate in the New York office. Cindy Abramson is an associate in the Litigation Department in the New York office of Morrison & Foerster LLP. She recieved her J.D. from the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she completed concentrations in Intellectual Property and Litigation and was Senior Notes Editor of the Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Morrison & Foerster, LLP. -

Investigating Hip-Hop's Emergence in the Spaces of Late Capitalism

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2008 Re-Taking it to the Streets: Investigating Hip-Hop's Emergence in the Spaces of Late Capitalism Kevin Waide Kosanovich College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kosanovich, Kevin Waide, "Re-Taking it to the Streets: Investigating Hip-Hop's Emergence in the Spaces of Late Capitalism" (2008). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626547. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-zyvx-b686 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Re-Taking it to the Streets: Investigating Hip-Hop’s Emergence in the Spaces of Late Capitalism Kevin Waide Kosanovich Saginaw, Michigan Bachelor of Arts, University of Michigan, 2003 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August, 2008 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts aide KosanovichKej Approved,by the Committee, May, 2008 imittee Chair Associate Pro rn, The College of William & Mary Associate Professor A lege of William & Mary Assistant P ressor John Gamber, The College of William & Mary ABSTRACT PAGE Much of the scholarship focusing on rap and hip-hop argues that these cultural forms represent instances of African American cultural resistance. -

1 the Versions Project: Exploring

THE VERSIONS PROJECT: EXPLORING MASHUP CULTURE By FRANCESCA LYN SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Benjamin DeVane, CHAIR Melinda McAdams, MEMBER James Oliverio, MEMBER A PROJECT IN LIEU OF THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 1 MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 2 ©2011 Francesca Lyn To everyone who has encouraged me to never give up, this would have never happened without all of you. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a pleasure to thank the many people who made this thesis possible. Thank you to my thesis chair Professor Ben DeVane and to my committee. I know that I was lucky enough to be guided by experts in their fields and I am extremely grateful for all of the assistance. I am grateful for every mashup artist that filled out a survey or simply retweeted a link. Special thanks goes to Kris Davis, the architect of idealMashup who encouraged me to become more of an activist with my work. And thank you to my parents and all of my friends. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………….4 ABSTRACT……..………………………………………………………………………………...6 INTRODUCTION..……………………………………………………………………………….7 Remix Culture and Broader Forms………………………………………………………………..9 EARLY ANTECEDENTS………………………………………………………………………10 Hip-hop…………………………………………………………………………………………..11 THE MODERN MASHUP ERA………………………………………………………………..13 NEW MEDIA ARTIFACTS…………………………………………………………………….14 The Hyperreal……………………………………………………………………………………15 Properties of New Media………………………………………………………………………...17 Community……………………………………………………………………………...…18 -

A Remix Manifesto

An Educational Guide About The Film In RiP: A remix manifesto, web activist and filmmaker Brett Gaylor explores issues of copyright in the information age, mashing up the media landscape of the 20th century and shattering the wall between users and producers. The film’s central protagonist is Girl Talk, a mash‐up musician topping the charts with his sample‐based songs. But is Girl Talk a paragon of people power or the Pied Piper of piracy? Creative Commons founder, Lawrence Lessig, Brazil’s Minister of Culture, Gilberto Gil, and pop culture critic Cory Doctorow also come along for the ride. This is a participatory media experiment from day one, in which Brett shares his raw footage at opensourcecinema.org for anyone to remix. This movie‐as‐mash‐up method allows these remixes to become an integral part of the film. With RiP: A remix manifesto, Gaylor and Girl Talk sound an urgent alarm and draw the lines of battle. Which side of the ideas war are you on? About The Guide While the film is best viewed in its entirety, the chapters have been summarized, and relevant discussion questions are provided for each. Many questions specifically relate to music or media studies but some are more general in nature. General questions may still be relevant to the arts, but cross over to social studies, law and current events. Selected resources are included at the end of the guide to help students with further research, and as references for material covered in the documentary. This guide was written and compiled by Adam Hodgins, a teacher of Music and Technology at Selwyn House School in Montreal, Quebec. -

ALLA Press Release May 26 2015 FINAL

! ! ! A$AP ROCKY’S NEW ALBUM AT.LONG.LAST.A$AP AVAILABLE NOW ON A$AP WORLDWIDE/POLO GROUNDS MUSIC/RCA RECORDS TRENDING NO. 1 ON ITUNES IN THE US, UK, CANADA, AUSTRALIA, FRANCE, GERMANY AND MORE SOPHOMORE ALBUM FEATURES APPEARANCES BY KANYE WEST, LIL WAYNE, ScHOOLBOY Q, MIGUEL, ROD STEWART, MARK RONSON, MOS DEF, JUICY J, JOE FOX AND OTHERS [New York, NY – May 26, 2015] A$AP Rocky released his highly anticipated new album, At.Long.Last.A$AP, today (5/26) due to the album leaking a week prior to its scheduled June 2nd release date. The album is currently No. 1 at iTunes in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, France, Germany, Denmark, Finland, New Zealand, Poland, Switzerland, Russia and more. The follow-up to the charismatic Harlem MC’s 2013 release, Long.Live.A$AP, A$AP Rocky’s sophomore album, features a stellar line up of guest appearances by Rod Stewart, Miguel and Mark Ronson on “Everyday,” ScHoolboy Q on “Electric Body,” Lil Wayne on a new version of the previously released “M’$,” Kanye West and Joe Fox on “Jukebox Joints,” plus Mos Def, Juicy J, UGK and more on other standout tracks. Producers Danger Mouse, Jim Jonsin, Juicy J and Mark Ronson among others, contributes to the album’s trippy new sound. Executive Producers include Danger Mouse, A$AP Yams and A$AP Rocky with Co-Executive Producers Hector Delgado, Juicy J, Chace Johnson, Bryan Leach and AWGE. In 2013, A$AP Rocky announced his global arrival in a major way with his chart- topping debut album LONG.LIVE.A$AP. -

Frank Musarra Multimedia Artist and Technologist Born in Cleveland OH, 1981 BA, Bard College, Annandale-On-Hudson, NY, 2003 Lives and Works in Brooklyn NY

Frank Musarra Multimedia Artist and Technologist Born in Cleveland OH, 1981 BA, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY, 2003 Lives and works in Brooklyn NY Selected Multimedia Fabrications 2019: Kunsthalle Basel, Dora Budor: ‘The Preserving Machine’, Basel, Switzerland ● Raspberry Pi & Arduino microcontroller programming, biomechanical flying bird controlled via bluetooth and custom javascript / node.js code. Flight pattern based on data taken from Beethoven's 9th symphony. Musical data was parsed with Ableton Live and a custom Max/MSP patch, data translated into Javascript. Nike, ‘Nike Soho: Department of Unimaginable’, New York, NY ● Kinetic sculpture commission for mixed media installation and window display at Nike’s 5-story Soho retail location. 3D printed components, Arduino microcontroller programming, LEDs, GPU liquid cooling system pumps and fans, UV sensitive paint and filament, reclaimed e-waste. Esther Klein Gallery, Laura Splan: ‘Remote Entanglements’, ‘Contested Territories’, Philadelphia, PA ● Designed, programmed, and fabricated custom networked sculptures. Modified fan, wireless Raspberry Pi control, adjusting wind speed in real time to data from a biological laboratory. Twitter actuated lab mixer, IOT microcontroller, networked control. Wonderspaces Gallery, Foo/Skou: ‘Harmony of Spheres’, San Diego, CA ● Prototyping, development and fabrication of an interactive light and sound sculpture. Eighty-one wooden spheres coated in touch-sensitive conductive paint triggering eighty-one audio loops of choral vocalists and eighty-one LED spotlights. Interactive spatial playback on eighteen separate audio channels. Arduino microcontroller programming, capacitive touch sensor, polyphonic audio module, programmable LEDs. Amaro Montenegro, ‘Zest’s Lab’, Brooklyn Bar Convention, Brooklyn, NY ● Interactive sculpture commission for immersive theater performance / experiential marketing campaign. Mixed media, custom audio synthesizer, lighting, peristaltic liquid pumps for elaborate cocktail mixing device. -

The Grey Album and Musical Composition in Configurable Culture

What Did Danger Mouse Do? The Grey Album and Musical Composition in Configurable Culture This article uses The Grey Album, Danger Mouse’s 2004 mashup of Jay-Z’s Black Album with the Beatles’“White Album,” to explore the ontological status of mashups, with a focus on determining what sort of creative work a mashup is. After situating the album in relation to other types of musical borrowing, I provide brief analyses of three of its tracks and build upon recent research in configurable-music practices to argue that the album is best conceptualized as a type of musical performance. Keywords: The Grey Album, The Black Album, the “White Album,” Danger Mouse, Jay-Z, the Beatles, mashup, configurable music. Downloaded from captions. What’s most embarrassing about this is how http://mts.oxfordjournals.org/ immensely improved both cartoons turned out to be.”2 n 1989 Gary Larson published The PreHistory of The Far Larson’s tantalizing use of quotation marks around “acci- Side, a retrospective of his groundbreaking cartoon. In a dentally” implies that the editor responsible for switching the I section of the book titled Mistakes—Mine and Theirs, captions may have done so deliberately. If we assume this to be Larson discussed a couple of curious instances when the Dayton the case and agree that both cartoons are improved, a number of Daily News switched the captions for The Far Side with the one questions emerge. What did the editor do? He/she did not for Dennis the Menace, its neighbor on the comics page. The come up with a concept, did not draw a cartoon, and did not first of these two instances had, by far, the funnier result: on the compose a caption. -

The Hood Internet Mixes It Up

CROSSFADER (//CROSSFADER.FM/) ARCHIVE (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/ARCHIVE/) APPS (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/APPS/) DJZ (http://www.djz.com/) CROSSFADER (//CROSSFADER.FM/) ARCHIVE (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/ARCHIVE/) APPS (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/APPS/) EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW INTERVIEW: THE HOOD INTERNET MIXES IT UP Kim Reyes • SEP 11, 2013 Tweet 1 Aaron Brink and Steve Reidell decided to break out into the mash-up music scene under the moniker The Hood Internet (http://www.djz.com/tag/the-hood- internet) in a time when the genre was hot. Brink and Reidell, known by their DJ names ABX and STV SLV, have been releasing free mash-up songs and mixes on their website since 2007. What began as an internet project has transformed overtime to incorporate live DJ sets and a studio album of original tracks. Before taking the stage at the San Francisco venue The Independent on August 17, Reidell briefly explained the history of how The Hood Internet came to be. “ABX and I had a history of experimenting with looped-based software, just kind of making fun beats out of songs for our friends to rap on. The internet at the time seemed to be really receptive to mashups and I think we wanted to approach them with a little different twist.” In order to set themselves apart from other mash-up peers like Girl Talk (http://illegal-art.net/girltalk/), The Hood Internet decided to curate music by fusing rap and hip-hop with indie and electronic music. These songs were not necessarily chosen for their mainstream popularity, but were tracks chosen from Brink and Reidell’s own personal library of music. -

Client and Artist List

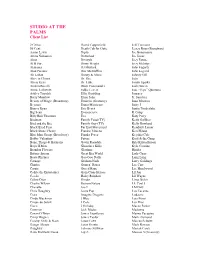

STUDIO AT THE PALMS Client List 2 Cellos David Copperfield Jeff Timmons 50 Cent Death Cab for Cutie Jersey Boys (Broadway) Aaron Lewis Diplo Joe Bonamassa Akina Nakamori Disturbed Joe Jonas Akon Divinyls Joey Fatone Al B Sure Dizzy Wright Joey McIntyre Alabama DJ Mustard John Fogarty Alan Parsons Doc McStuffins John Legend Ali Lohan Donny & Marie Johnny Gill Alice in Chains Dr. Dre JoJo Alicia Keys Dr. Luke Jordin Sparks Andrea Bocelli Duck Commander Josh Gracin Annie Leibovitz Eddie Levert Jose “Pepe” Quintano Ashley Tinsdale Ellie Goulding Journey Barry Manilow Elton John Jr. Sanchez Beauty of Magic (Broadway) Eminem (Grammy) Juan Montero Beyonce Ennio Morricone Juicy J Bianca Ryan Eric Benet Justin Timberlake Big Sean Evanescence K Camp Billy Bob Thornton Eve Katy Perry Birdman Family Feud (TV) Keith Galliher Bird and the Bee Family Guy (TV) Kelly Rowland Black Eyed Peas Far East Movement Kendrick Lamar Black Stone Cherry Frankie Moreno Keri Hilson Blue Man Group (Broadway) Franky Perez Keyshia Cole Bobby Valentino Future Kool & the Gang Bone, Thugs & Harmony Gavin Rossdale Kris Kristofferson Boyz II Men Ghostface Killa Kyle Cousins Brandon Flowers Gloriana Hinder Britney Spears Great Big World Lady Gaga Busta Rhymes Goo Goo Dolls Lang Lang Carnage Graham Nash Larry Goldings Charise Guns n’ Roses Lee Carr Cassie Gucci Mane Lee Hazelwood Cedric the Entertainer Gym Class Heroes Lil Jon Cee-lo Haley Reinhart Lil Wayne Celine Dion Hinder Limp Bizkit Charlie Wilson Human Nature LL Cool J Chevelle Ice-T LMFAO Chris Daughtry Icona Pop Los -

Serra-Joan-Identification-Of-Versions

Identification of Versions of the Same Musical Composition by Processing Audio Descriptions Joan Serrà Julià TESI DOCTORAL UPF / 2011 Director de la tesi: Dr. Xavier Serra i Casals Dept. of Information and Communication Technologies Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Copyright c Joan Serrà Julià, 2011. Dissertation submitted to the Deptartment of Information and Communica- tion Technologies of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR PER LA UNIVERSITAT POMPEU FABRA, with the mention of European Doctor. Music Technology Group (http://mtg.upf.edu), Dept. of Information and Communica- tion Technologies (http://www.upf.edu/dtic), Universitat Pompeu Fabra (http://www. upf.edu), Barcelona, Spain. Als meus avis. Acknowledgements I remember I was quite shocked when, one of the very first times I went to the MTG, Perfecto Herrera suggested that I work on the automatic identification of versions of musical pieces. I had played versions (both amateur and pro- fessionally) since I was 13 but, although being familiar with many MIR tasks, I had never thought of version identification before. Furthermore, how could they (the MTG people) know that I played song versions? I don’t think I had told them anything about this aspect... Before that meeting with Perfe, I had discussed a few research topics with Xavier Serra and, after he gave me feedback on a number of research proposals I had, I decided to submit one related to the exploitation of the temporal information of music descriptors for music similarity. Therefore, when Perfe suggested the topic of version identification I initially thought that such a suggestion was not related to my proposal at all. -

Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. V. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music, 45 Hastings L.J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 45 | Issue 2 Article 4 1-1994 Thou hS alt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music Carl A. Falstrom Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Carl A. Falstrom, Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music, 45 Hastings L.J. 359 (1994). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol45/iss2/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music by CARL A. FALSTROM* Introduction Digital sound sampling,1 the borrowing2 of parts of sound record- ings and the subsequent incorporations of those parts into a new re- cording,3 continues to be a source of controversy in the law.4 Part of * J.D. Candidate, 1994; B.A. University of Chicago, 1990. The people whom I wish to thank may be divided into four groups: (1) My family, for reasons that go unstated; (2) My friends and cohorts at WHPK-FM, Chicago, from 1986 to 1990, with whom I had more fun and learned more things about music and life than a person has a right to; (3) Those who edited and shaped this Note, without whom it would have looked a whole lot worse in print; and (4) Especially special persons-Robert Adam Smith, who, among other things, introduced me to rap music and inspired and nurtured my appreciation of it; and Leah Goldberg, who not only put up with a whole ton of stuff for my three years of law school, but who also managed to radiate love, understanding, and support during that trying time.