The Art of Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

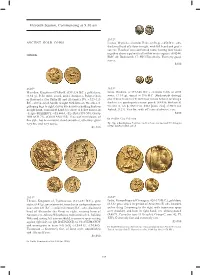

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt. -

American Journal of Numismatics 26

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF NUMISMATICS 26 Second Series, continuing The American Numismatic Society Museum Notes THE AMERICAN NUMISMATIC SOCIETY NEW YORK 2014 © 2014 The American Numismatic Society ISSN: 1053-8356 ISBN 978-0-89722-336-2 Printed in China Contents Editorial Committee v Jonathan Kagan. Notes on the Coinage of Mende 1 Evangeline Markou, Andreas Charalambous and Vasiliki Kassianidou. pXRF Analysis of Cypriot Gold Coins of the Classical Period 33 Panagiotis P. Iossif. The Last Seleucids in Phoenicia: Juggling Civic and Royal Identity 61 Elizabeth Wolfram Thill. The Emperor in Action: Group Scenes in Trajanic Coins and Monumental Reliefs 89 Florian Haymann The Hadrianic Silver Coinage of Aegeae (Cilicia) 143 Jack Nurpetlian. Damascene Tetradrachms of Caracalla 187 Dario Calomino. Bilingual Coins of Severus Alexander in the Eastern Provinces 199 Saúl Roll-Vélez. The Pre-reform CONCORDIA MILITVM Antoniniani of Maximianus: Their Problematic Attribution and Their Role in Diocletian’s Reform of the Coinage 223 Daniela Williams. Digging in the Archives: A Late Roman Coin Assemblage from the Synagogue at Ancient Ostia (Italy) 245 François de Callataÿ. How Poor are Current Bibliometrics in the Humanities? Numismatic Literature as a Case Study 275 Michael Fedorov. Early Mediaeval Chachian Coins with Trident-Shaped Tamghas, and Some Others 317 Antonino Crisà. An Eighteenth-Century Sicilian Coin Hoard from the Termini-Cerda Railway Construction Site (Palermo, 1869) 339 Review Articles 363 American Journal of Numismatics Andrew R. Meadows Oliver D. Hoover Editor Managing Editor Editorial Committee John W. Adams John H. Kroll Boston, Massachusetts Oxford, England Jere L. Bacharach Eric P. Newman University of Washington St. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Dying by the Sword: Did the Severan Dynasty Owe Its Downfall to Its Ultimate Failure to Live up to Its Own Militaristic Identity?

Dying by the Sword: Did the Severan dynasty owe its downfall to its ultimate failure to live up to its own militaristic identity? Exam Number: B043183 Master of Arts with Honours in Classical Studies Exam Number: B043183 1 Acknowledgements Warm thanks to Dr Matthew Hoskin for his keen supervision, and to Dr Alex Imrie for playing devil’s advocate and putting up with my daft questions. Thanks must also go to my family whose optimism and belief in my ability so often outweighs my own. Exam Number: B043183 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One – Living by the Sword 6 Chapter Two – Dying by the Sword 23 Chapter Three – Of Rocky Ground and Great Expectations 38 Conclusion 45 Bibliography 48 Word Count: 14,000 Exam Number: B043183 3 List of Illustrations Fig. 1. Chart detailing the percentage of military coin types promoted by emperors from Pertinax to Numerian inclusive (Source: Manders, E. (2012), Coining Images of Power: Patterns in the Representation of Roman Emperors on Imperial Coinage, AD 193-284, Leiden, p. 65, fig. 17). Fig. 2. Portrait statue showing Caracalla in full military guise (Source: https://www.dailysabah.com/history/2016/08/02/worlds-only-single-piece-2nd-century- caracalla-statue-discovered-in-southern-turkey (Accessed 14/01/17). Fig. 3. Bust of Caracalla wearing sword strap and paludamentum (Source: Leander Touati, A.M. (1991), ‘Portrait and historical relief. Some remarks on the meaning of Caracalla’s sole ruler portrait’, in A.M. Leander Touati, E. Rystedt, and O. Wikander (eds.), Munusula Romana, Stockholm, 117-31, p. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is an author's version which may differ from the publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/94472 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-30 and may be subject to change. Identities of emperor and empire in the third century AD By Erika Manders and Olivier Hekster1 In AD 238, at what is now called Gressenich, near Aachen, an altar was dedicated with the following inscription: [to Iupiter Optimus Maximus]/ and the genius of the place for/ the safety of the empire Ma/ sius Ianuari and Ti/ tianus Ianuari have kept their promise freely to the god who deserved it, under the care /of Masius, mentioned above, and of Macer Acceptus, in [the consulship] of Pius and Proclus ([I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo)] et genio loci pro salute imperi Masius Ianuari et Titianus Ianuari v(otum) s(olverunt) l(ibentes) m(erito) sub cura Masi s(upra) s(cripti) et Maceri Accepti, Pio et Proclo [cos.]).2 Far in the periphery of the Roman Empire, two men vowed to the supreme god of Rome and the local genius, not for the safety of the current rulers, but for that of the Empire as a whole. Few sources illustrate as clearly how, fairly early in the third century already, the Empire was thought, at least by some, to be under threat. At the same time though, the inscription makes clear how the Empire as a whole was perceived as a communal identity which had to be safeguarded by centre and periphery alike. -

Roman Coins Elementary Manual

^1 If5*« ^IP _\i * K -- ' t| Wk '^ ^. 1 Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google PROTAT BROTHERS, PRINTBRS, MACON (PRANCi) Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL COMPILED BY CAV. FRANCESCO gNECCHI VICE-PRBSIDENT OF THE ITALIAN NUMISMATIC SOaETT, HONORARY MEMBER OF THE LONDON, BELGIAN AND SWISS NUMISMATIC SOCIBTIES. 2"^ EDITION RKVISRD, CORRECTED AND AMPLIFIED Translated by the Rev<> Alfred Watson HANDS MEMBF,R OP THE LONDON NUMISMATIC SOCIETT LONDON SPINK & SON 17 & l8 PICCADILLY W. — I & 2 GRACECHURCH ST. B.C. 1903 (ALL RIGHTS RF^ERVED) Digitized by Google Arc //-/7^. K.^ Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL AUTHOR S PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION In the month of July 1898 the Rev. A. W. Hands, with whom I had become acquainted through our common interests and stud- ieSy wrote to me asking whether it would be agreeable to me and reasonable to translate and publish in English my little manual of the Roman Coinage, and most kindly offering to assist me, if my knowledge of the English language was not sufficient. Feeling honoured by the request, and happy indeed to give any assistance I could in rendering this science popular in other coun- tries as well as my own, I suggested that it would he probably less trouble ii he would undertake the translation himselt; and it was with much pleasure and thankfulness that I found this proposal was accepted. It happened that the first edition of my Manual was then nearly exhausted, and by waiting a short time I should be able to offer to the English reader the translation of the second edition, which was being rapidly prepared with additions and improvements. -

Framing the Sun: the Arch of Constantine and the Roman Cityscape Elizabeth Marlowe

Framing the Sun: The Arch of Constantine and the Roman Cityscape Elizabeth Marlowe To illustrate sonif oi the key paradigm shifts of their disci- C^onstantine by considering the ways its topographical setting pline, art historians often point to the fluctuating fortunes of articulates a relation between the emperor's military \ictoiy ihe Arrh of Constantine. Reviled by Raphael, revered by Alois and the favor of the sun god.'' Riegl, condemned anew by the reactionary Bernard Beren- son and conscripted by the openly Marxist Ranucchio Bian- The Position of the Arch rhi Bandineili, the arch has .sened many agendas.' Despite In Rome, triumphal arches usually straddled the (relatively their widely divergent conclusions, however, these scholars all fixed) route of the triumphal procession.^ Constantine's share a focus on the internal logic of the arcb's decorative Arch, built between 312 and 315 to celebrate his victory over program. Time and again, the naturalism of the monument's the Rome-based usuiper Maxentius (r. 306-12) in a bloody spoliated, second-century reliefs is compared to the less or- civil war, occupied prime real estate, for the options along ganic, hieratic style f)f the fourth-<:entur\'canings. Out of that the "Via Triumphalis" (a modern term but a handy one) must contrast, sweeping theorie.s of regrettable, passive decline or have been rather limited by Constantine's day. The monu- meaningful, active transformation are constructed. This ment was built at the end of one of the longest, straightest methodology' has persisted at the expense of any analysis of stretches along the route, running from the southern end of the structure in its urban context. -

Papal Overlordship and Protectio of the King, C.1000-1300

1 PAPAL OVERLORDSHIP AND PROTECTIO OF THE KING, c.1000-1300 Benedict Wiedemann UCL Submitted for the degree of PhD in History 2017 2 I, Benedict Wiedemann, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Papal Overlordship and Protectio of the King, c.1000-1300 Abstract This thesis focuses on papal overlordship of monarchs in the middle ages. It examines the nature of alliances between popes and kings which have traditionally been called ‘feudal’ or – more recently – ‘protective’. Previous scholarship has assumed that there was a distinction between kingdoms under papal protection and kingdoms under papal overlordship. I argue that protection and feudal overlordship were distinct categories only from the later twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. Before then, papal-royal alliances tended to be ad hoc and did not take on more general forms. At the beginning of the thirteenth century kingdoms started to be called ‘fiefs’ of the papacy. This new type of relationship came from England, when King John surrendered his kingdoms to the papacy in 1213. From then on this ‘feudal’ relationship was applied to the pope’s relationship with the king of Sicily. This new – more codified – feudal relationship seems to have been introduced to the papacy by the English royal court rather than by another source such as learned Italian jurists, as might have been expected. A common assumption about how papal overlordship worked is that it came about because of the active attempts of an over-mighty papacy to advance its power for its own sake. -

Classical Perspectives at the End of Antiquity

Classical Perspectives at the End of Antiquity: Author: Jakob Froelich Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:107418 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2017 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Classical Perspectives at the End of Antiquity Jakob Froelich Advisor: Mark Thatcher Boston College Department of Classical Studies April 2017 Truly, when [Constantius] came to the forum of Trajan, a unique construction under the heavens, as we deem, likewise deemed a marvel by the gods, he was stopped and was transfixed, as he wrapped his mind around the giant structures, which are not describable nor will they be achieved again by mortals.1 This quote from Ammianus’ long description of Constantius II’s adventus to Rome in 357 CE is the culmination of the emperor’s tour of Rome during a triumphal procession. He passes through the city and sees “[the] glories of the Eternal City,”2 before finally reaching Trajan’s Forum. Constantius is struck with awe when he sees Rome for the first time–in much the same way a tourist might today when walking through Rome. Rome loomed large in the Roman consciousness with the city’s 1000-year history and the monuments, which populated the urban space and, in many ways, physically embodies that history. This status was so ingrained that even in the fourth century when the city had lost much of its significance, “[Constantius] was eager to see Rome.”3 Ammianus deems Constantius’ awe to be appropriate as he describes the forum as a “unique construction;” however, he ends this statement with a pronouncement that men will not attain an accomplishment of that caliber again. -

Romans on Parade: Representations of Romanness in the Triumph

ROMANS ON PARADE: REPRESENTATIONS OF ROMANNESS IN THE TRIUMPH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfullment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Amber D. Lunsford, B.A., M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Erik Gunderson, Adviser Professor William Batstone Adviser Professor Victoria Wohl Department of Greek and Latin Copyright by Amber Dawn Lunsford 2004 ABSTRACT We find in the Roman triumph one of the most dazzling examples of the theme of spectacle in Roman culture. The triumph, though, was much more than a parade thrown in honor of a conquering general. Nearly every aspect of this tribute has the feel of theatricality. Even the fact that it was not voluntarily bestowed upon a general has characteristics of a spectacle. One must work to present oneself as worthy of a triumph in order to gain one; military victories alone are not enough. Looking at the machinations behind being granted a triumph may possibly lead to a better understanding of how important self-representation was to the Romans. The triumph itself is, quite obviously, a spectacle. However, within the triumph, smaller and more intricate spectacles are staged. The Roman audience, the captured people and spoils, and the triumphant general himself are all intermeshed into a complex web of spectacle and spectator. Not only is the triumph itself a spectacle of a victorious general, but it also contains sub-spectacles, which, when analyzed, may give us clues as to how the Romans looked upon non-Romans and, in turn, how they saw themselves in relation to others. -

The Imperial Cult During the Reign of Domitian

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Filosofická fakulta Katedra archeologie a muzeologie Klasická archeologie Bc. Barbora Chabrečková Cisársky kult v období vlády Domitiána Magisterská diplomová práca Vedúca práce: Mgr. Dagmar Vachůtová, Ph.D. Brno 2017 MASARYK UNIVERSITY Faculty of Arts Department of Archaeology and Museology Classical Archaeology Bc. Barbora Chabrečková The Imperial Cult During the Reign of Domitian Master's Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Dagmar Vachůtová, Ph.D. Brno 2017 2 I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work, created with use of primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ……………………………… Bc. Barbora Chabrečková In Brno, June 2017 3 Acknowledgement I would like to thank to my supervisor, Mgr. Dagmar Vachůtová, Ph.D., for her guidance and encouragement that she granted me throughout the entire creative process of this thesis, to my consulting advisor, Mgr. Ing. Monika Koróniová, who showed me the possibilities this topic has to offer, and to my friends and parents, for their care and support. 4 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 7 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 8 I) Definition, Origin, and Pre-Imperial History of the Imperial Cult ................................... 10 1.) Origin in the Private Cult & the Term Genius ........................................................... 10 -

Cover Page.Ai

CULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONS: DEPICTIONS OF ARCHITECTURE IN ROMAN STATE RELIEFS Elizabeth Wolfram Thill A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Dr. Monika Truemper Dr. Sheila Dillon Dr. Lidewijde de Jong Dr. Mary Sturgeon Dr. Richard Talbert ABSTRACT ELIZABETH WOLFRAM THILL: Cultural Constructions: Depictions of Architecture in Roman State Reliefs (Under the direction of Monika Truemper) Architectural depictions are an important window into crucial conceptual connections between architecture and culture in the Roman Empire. While previous scholarship has treated depictions of architecture as topographic markers, I argue that architectural depictions frequently served as potent cultural symbols, acting within the broader themes and ideological messages of sculptural monuments. This is true both for representations of particular historic buildings (identifiable depictions), and for the far more numerous depictions that were never meant to be identified with a specific structure (generic depictions). This latter category of depictions has been almost completely unexplored in scholarship. This dissertation seeks to fill this gap, and to situate architectural depictions within scholarship on state reliefs as a medium for political and ideological expression. I explore the ways in which architectural depictions, both identifiable and generic, were employed in state-sponsored sculptural monuments, or state reliefs, in the first and second centuries CE in and around the city of Rome. My work is innovative in combining the iconographic and iconological analysis of architectural depictions with theoretical approaches to the symbolism of built architecture, drawn from studies on acculturation (“Romanization”), colonial interactions, and imperialism.