The Visual Languages of the Columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius and Their Artistic Representation of Rome's Barbarian Enemies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domitian's Dacian War Domitian'in Daçya Savaşi

2020, Yıl 4, Sayı 13, 75 - 102 DOMITIAN’S DACIAN WAR DOMITIAN’IN DAÇYA SAVAŞI DOI: 10.33404/anasay.714329 Çalışma Türü: Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article1 Gökhan TEKİR* ABSTRACT Domitian, who was one of the most vilified Roman emperors, had suf- fered damnatio memoriae by the senate after his assassination in 96. Senator historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio ignored and criticized many of Domitian’s accomplishments, including the Dacian campaign. Despite initial setbacks in 86 and 87, Domitian managed to push the invading Dacians into the Dacian terri- tory and even approached to the Dacian capital in 88. However, the Saturninus revolt and instability in the Chatti and Pannonia in 89 prevented Domitian from concluding the campaign. The peace treaty stopped the Dacian incursions and made Dacia a dependent state. It is consistent with Domitian’s non-expansionist imperial policy. This peace treaty stabilized a hostile area and turned Dacia a client kingdom. After dealing with various threats, he strengthened the auxiliary forces in Dacia, stabilizing the Dacian frontier. Domitian’s these new endeavors opened the way of the area’s total subjugation by Trajan in 106. Keywords: Domitian, Roman Empire, Dacia, Decebalus, security 1- Makale Geliş Tarihi: 03. 04. 2020 Makale Kabül Tarihi: 15. 08. 2020 * Doktor, Email: [email protected] ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3985-7442 75 DomItIan’s DacIan War ÖZ Domitian 96 yılında düzenlenen suikast sonucunda hakkında senato tarafından ‘hatırası lanetlenen’ ve hakkında en çok karalama yapılan Roma imparatorlarından birisidir. Senatör tarihçilerden olan Tacitus ve Cassius Dio, Domitian’ın bir çok başarısını görmezden gelmiş ve eleştirmiştir. -

Resettlement Into Roman Territory Across the Rhine and the Danube Under the Early Empire (To the Marcomannic Wars)*

Eos C 2013 / fasciculus extra ordinem editus electronicus ISSN 0012-7825 RESETTLEMENT INTO ROMAN TERRITORY ACROSS THE RHINE AND THE DANUBE UNDER THE EARLY EMPIRE (TO THE MARCOMANNIC WARS)* By LESZEK MROZEWICZ The purpose of this paper is to investigate the resettling of tribes from across the Rhine and the Danube onto their Roman side as part of the Roman limes policy, an important factor making the frontier easier to defend and one way of treating the population settled in the vicinity of the Empire’s borders. The temporal framework set in the title follows from both the state of preser- vation of sources attesting resettling operations as regards the first two hundred years of the Empire, the turn of the eras and the time of the Marcomannic Wars, and from the stark difference in the nature of those resettlements between the times of the Julio-Claudian emperors on the one hand, and of Marcus Aurelius on the other. Such, too, is the thesis of the article: that the resettlements of the period of the Marcomannic Wars were a sign heralding the resettlements that would come in late antiquity1, forced by peoples pressing against the river line, and eventu- ally taking place completely out of Rome’s control. Under the Julio-Claudian dynasty, on the other hand, the Romans were in total control of the situation and transferring whole tribes into the territory of the Empire was symptomatic of their active border policies. There is one more reason to list, compare and analyse Roman resettlement operations: for the early Empire period, the literature on the subject is very much dominated by studies into individual tribe transfers, and works whose range en- * Originally published in Polish in “Eos” LXXV 1987, fasc. -

Annual State 4-H Show and Sale on Campus Today

THE SPECTRUM VOLUME LVIII Z 545a STATE COLLEGE STATION, NORTH DAKOTA, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 30, 1942 NUMBER 4 Scabbard and Blade We Did Our Part Bismarck, N. D. Oct. 23, 1942 Annual State 4-H Dr. Frank L. Eversull, NDAC President: Elects Twelve Juniors I want to personally thank your faculty and student body for your Twelve juniors with payroll splendid part in the saving of North Show And Sale Dakota crops. Not only has the statis in the advanced ROTC actual work you have performed been of tremendous importance, but equally course have been elected to Scab- important has been the lift in morale bard and Blade, national honorary Marine, V-1 resulting from youth of the state lay- military fraternity for ROTC stu- ing aside educational pursuits to help On Campus Today our farmers in their hour of need. The dents. schools of the state have made an out- Confusion Is standing contribution to victory. Livestock and poultry exhibits for the 17th annual They are: John Moses, Richard Carley Governor. North Dakota 4-H club show and market sale were in place Waldo Gerlitz Explained this morning in the NDAC judging pavilion and exhibitors Sam Hess Bruce Hoverson Students enlisting in the navy were preparing their animals for James Kyser V-1 and the marine reserve pro- the judges who will judge all ex- Ellsworth Moe grams may not be enrolled in Paper Gets hibits tomorrow. Sale of the ani- Arvid Melby ROTC at the time of their enlist- mals is scheduled for Monday, Roy Gordon ment, but are allowed to take the according to H. -

Bullard Eva 2013 MA.Pdf

Marcomannia in the making. by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Greek and Roman Studies Eva Bullard 2013 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Marcomannia in the making by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 Supervisory Committee Dr. John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member During the last stages of the Marcommani Wars in the late second century A.D., Roman literary sources recorded that the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was planning to annex the Germanic territory of the Marcomannic and Quadic tribes. This work will propose that Marcus Aurelius was going to create a province called Marcomannia. The thesis will be supported by archaeological data originating from excavations in the Roman installation at Mušov, Moravia, Czech Republic. The investigation will examine the history of the non-Roman region beyond the northern Danubian frontier, the character of Roman occupation and creation of other Roman provinces on the Danube, and consult primary sources and modern research on the topic of Roman expansion and empire building during the principate. iv Table of Contents Supervisory Committee ..................................................................................................... -

The City's Memory: Texts of Preservation and Loss in Imperial St. Petersburg Julie Buckler, Harvard University Petersburg's Im

The City’s Memory: Texts of Preservation and Loss in Imperial St. Petersburg Julie Buckler, Harvard University Petersburg's imperial-era chroniclers have displayed a persistent, paradoxical obsession with this very young city's history and memory. Count Francesco Algarotti was among the first to exhibit this curious conflation of old and new, although he seems to have been influenced by sentiments generally in the air during the early eighteenth century. Algarotti attributed the dilapidated state of the grand palaces along the banks of the Neva to the haste with which these residences had been constructed by members of the court whom Peter the Great had obliged to move from Moscow to the new capital: [I]t is easy to see that [the palaces] were built out of obedience rather than choice. Their walls are all cracked, quite out of perpendicular, and ready to fall. It has been wittily enough said, that ruins make themselves in other places, but that they were built at Petersburg. Accordingly, it is necessary every moment, in this new capital, to repair the foundations of the buildings, and its inhabitants built incessantly; as well for this reason, as on account of the instability of the ground and of the bad quality of the materials.1 In a similar vein, William Kinglake, who visited Petersburg in the mid-1840s, scornfully advised travelers to admire the city by moonlight, so as to avoid seeing, “with too critical an eye, plaster scaling from the white-washed walls, and frost-cracks rending the painted 1Francesco Algarotti, “Letters from Count Algarotti to Lord Hervey and the Marquis Scipio Maffei,” Letter IV, June 30, 1739. -

2013 Virginia Senior Classical League State Finals Certamen Level III NOTE to MODERATORS: in Answers, Information in Parentheses Is Optional Extra Information

2013 Virginia Senior Classical League State Finals Certamen Level III NOTE TO MODERATORS: in answers, information in parentheses is optional extra information. A slash ( / ) indicates an alternate answer. Underlined portions of a longer, narrative answer indicate required information. ROUND ONE 1. TOSSUP: From what Latin noun, with what meaning, do the words ignition and igneous ultimately derive? ANS: IGNIS, FIRE BONUS: From what Latin verb, with what meaning, do the words coherent and adhesion derive? ANS: HAEREŌ, STICK/CLING 2. TOSSUP: According to Livy and Plutarch, what legendary Roman triumphed four times, was dictator five times, was never once consul, was honored with the title “Second Founder of Rome,” and conquered the city of Veii in 396 BC? ANS: (M. FURIUS) CAMILLUS BONUS: Following the victory over Veii, for what accusation did his political adversaries impeach Camillus? ANS: EMBEZZLEMENT 3. TOSSUP: According to Hesiod, what moon titan, the daughter of Ouranos and Gaia, bore Leto from the union with her brother Coeus? ANS: PHOEBE BONUS: According to Hesiod, what Star goddess was also the daughter of Phoebe and Coeus and the mother of Hecate? ANS: Asteria 4. TOSSUP: What fifteen-book work of Ovid ends with the apotheosis of Julius Caesar? ANS: METAMORPHOSES BONUS: What other work of Ovid, consisting of epistolary poems written by mythological heroines, allowed him to claim that he had created a new genre of mythological elegy? ANS: HEROIDES rd 5. TOSSUP: Give the 3 person singular, pluperfect active subjunctive of noceō, nocēre. ANS: NOCUISSET nd BONUS: Now give the 2 person plural present subjunctive of morior, morī. -

Analecta Romana Instituti Danici Xxxv/Xxxvi

ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI XXXV/XXXVI ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI XXXV/XXXVI 2010/11 ROMAE MMX-MMXI ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI XXXV-XXXVI © 2011 Accademia di Danimarca ISSN 2035-2506 Published with the support of a grant from: Det Frie Forskningsråd / Kultur og Kommunikation SCIENTIFIC BOARD Ove Hornby (Bestyrelsesformand, Det Danske Institut i Rom) Jesper Carlsen (Syddansk Universitet) Astrid Elbek (Det Jyske Musikkonservatorium) Karsten Friis-Jensen (Københavns Universitet) Helge Gamrath (Aalborg Universitet) Maria Fabricius Hansen (Ny Carlsbergfondet) Michael Herslund (Copenhagen Business School) Hannemarie Ragn Jensen (Københavns Universitet) Kurt Villads Jensen (Syddansk Universitet) Mogens Nykjær (Aarhus Universitet) Gunnar Ortmann (Det Danske Ambassade i Rom) Bodil Bundgaard Rasmussen (Nationalmuseet, København) Birger Riis-Jørgensen (Det Danske Ambassade i Rom) Lene Schøsler (Københavns Universitet) Poul Schülein (Arkitema, København) Anne Sejten (Roskilde Universitet) EDITORIAL BOARD Marianne Pade (Chair of Editorial Board, Det Danske Institut i Rom) Erik Bach (Det Danske Institut i Rom) Patrick Kragelund (Danmarks Kunstbibliotek) Gitte Lønstrup Dal Santo (Det Danske Institut i Rom) Gert Sørensen (Københavns Universitet) Birgit Tang (Det Danske Institut i Rom) Maria Adelaide Zocchi (Det Danske Institut i Rom) Analecta Romana Instituti Danici. — Vol. I (1960) — . Copenhagen: Munksgaard. From 1985: Rome, «L’ERMA» di Bretschneider. From 2007 (online): Accademia di Danimarca ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI encourages scholarly contributions within the Academy’s research fields. All contributions will be peer reviewed. Manuscripts to be considered for publication should be sent to: [email protected]. Authors are requested to consult the journal’s guidelines at www.acdan.it. Contents STINE BIRK Third-Century Sarcophagi from the City of Rome: A Chronological Reappraisal 7 URSULA LEHMANN-BROCKHAUS Asger Jorn: Il grande rilievo nell’Aarhus Statgymnasium 31 METTE MIDTGÅRD MADSEN: Sonne’s Frieze versus Salto’s Reconstruction. -

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

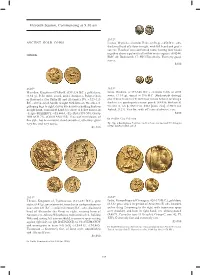

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt. -

Marcus Aurelius' Rain Miracle: When and Where?1 Péter Kovács

šTUDIJNÉ ZVESTI ARCHEOLOGICKÉHO ÚSTAVU SAV 62, 2017, 101 – 111 MARCUS AURELIUS’ rAIN MIRACLE: WHEN AND WHERE?1 Péter Kovács Key words: Marcus Aurelius, Pannonia, rain miracle, Barbaricum, Marcomannic wars Kľúčové slová: Marcus Aurelius, Pannonia, zázračný dážď, barbari- kum, markomanské vojny Marcus Aurelius’ rain miracle: when and where? In his paper the author deals with the two most important problems of the rain miracle during Marcus Aurelius’ campaign against the Quadi: where and when did it happen. After examining the written sources (esp. the accounts of Cassius Dio, the vita Marci of the Historia Augusta, Tertullianus and Eusebius and Marcus Aurelius’ forged letter) and the depictions of the Antonine Column in Rome (scenes XI and XVI), the author comes to the conclusion that there were two miracles (lightning and rain miracles: the former one in the presence of the emperor) the year could be 172 AD (but 171 cannot be excluded either) and the miracle happened probably in the borders of the Quadi and the Cotini. The ancient and medieval sources on Marcus Aurelius’ Marcomannic-Sarmatian wars usually highlight two events.2 The first of these occurred during the first war between AD 169 and 175, when divine intervention – a lightning and rain miracle – saved the Roman troops, which were surrounded by the enemy and were suffering from a water shortage. Thunderbolts struck the Germans, while rain soothed the Romans’ suffering. The Column of Marcus Aurelius depicted the miracles in two different scenes narrating the first Roman campaign in the Barbaricum (Scenes XI and XVI; Fig. 1; 2), clear testi- mony that the lightning and rain miracle were two different events.3 Among the written sources, only the account in the vita Marci in the Historia Augusta separates them: fulmen de caelo precibus suis contra hostium machinamentum extorsit, su<i>s pluvia impetrata, cum siti laborarent (24.4). -

The Remaking of the Dacian Identity in Romania and the Romanian Diaspora

THE REMAKING OF THE DACIAN IDENTITY IN ROMANIA AND THE ROMANIAN DIASPORA By Lucian Rosca A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Sociology Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2015 George Mason University, Fairfax, VA The Remaking of the Dacian Identity in Romania and the Romanian Diaspora A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University By Lucian I. Rosca Bachelor of Arts George Mason University, 2015 Director: Patricia Masters, Professor Department of Sociology Fall Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis coordinators: Professor Patricia Masters, Professor Dae Young Kim, Professor Lester Kurtz, and my wife Paula, who were of invaluable help. Fi- nally, thanks go out to the Fenwick Library for providing a clean, quiet, and well- equipped repository in which to work. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables................................................................................................................... v List of Figures ............................................................................................................... -

165 Years of Roman Rule on the Left Bank of the Danube. at The

92 Chapter III PROVINCIA DACIA AUGUSTI: 165 years of Roman rule on the left bank of the Danube. At the beginning of the 2nd century, in the Spring of 101AD, Roman Forces marched against the Kingdom of Decebal. We already know what the Roman's rationale was for starting this war and we also know that the real reason was likely to have been the personal ambition of the first Provincial Emperor, Trajan (he was born in Hispania a man of Macedonian background among Greeks). The Roman armies marched against a client-state of Rome, which was a subordinate ally of Rome. Decebal did not want to wage war against Rome and his recurring peace offers confirm this. It is unlikely that Trajan would only have decided on the total conquest of the Dacian Kingdom after he waged his first campaign in 101-102. After this, Roman garrisons were established in the Province - their ongoing presence is reflected by the Latin names of towns (as recorded by Ptolemy). At Dobreta they begin to build the stone bridge which will span the Danube. It was built in accordance with plans made by Apollodorus of Damascus to promote continuous traffic - it was an accomplishment unmatched - even by Rome. This vast project portends that Trajan began the expedition against Dacia in 101 with the intention of incorporating the Kingdom into the Roman Empire. The Emperor, who founded a city (Nicopolis) to commemorate his victory over Dacia, has embarked on this campaign not only for reasons of personal ambition. The 93 economic situation of the Empire was dismal at the beginning of Trajan's reign; by the end of the second Dacian War it has vastly improved. -

Was Galatian Really Celtic? Anthony Durham & Michael Goormachtigh First Published November 2011, Updated to October 2016

Was Galatian Really Celtic? Anthony Durham & Michael Goormachtigh first published November 2011, updated to October 2016 Summary Saint Jerome’s AD 386 remark that the language of ancient Galatia (around modern Ankara) resembled the language of the Treveri (around modern Trier) has been misinterpreted. The “Celts”, “Gauls” or “Galatians” mentioned by classical authors, including those who invaded Greece and Anatolia around 277 BC, were not Celtic in the modern sense of speaking a Celtic language related to Welsh and Irish, but tall, pale-skinned, hairy, warrior peoples from the north. The 150 or so words and proper names currently known from Galatian speech show little affinity with Celtic but more with Germanic. Introduction In AD 386 Saint Jerome wrote: Apart from the Greek language, which is spoken throughout the entire East, the Galatians have their own language, almost the same as the Treveri. For many people this short remark is the linchpin of a belief that ancient Celtic speech spread far outside its Atlantic-fringe homeland, reaching even into the heart of Anatolia, modern Turkey. However, we wish to challenge the idea that Galatians spoke a language that was Celtic in the modern sense of being closely related to Welsh or Irish. Galatia was the region around ancient Ancyra, modern Ankara, in the middle of Turkey. Anatolia (otherwise known as Asia Minor) has seen many civilisations come and go over the millennia. Around 8000 BC it was a cradle of agriculture and the Neolithic revolution. The whole family of Indo-European languages originated somewhere in that region. We favour the idea that they grew up around the Black Sea all the way from northern Anatolia, past the mouth of the river Danube, to southern Russia and Ukraine.