A Cosmopolitan Defence of International Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018–2019 Information Pack Mathematical Literacy Reading

ISA International Schools’ Assessment ISAInternational Schools’ Assessment 2018–2019 Information Pack Mathematical Literacy Reading Writing Scientific Literacy Australian Council for Educational Research What is the ISA? The ISA is a set of tests used by international schools and schools with an international focus to monitor student performance over time and confirm that their internal assessments are aligned with international expectations of performance. Designed and developed by the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER), the ISA reading, mathematical literacy and scientific literacy assessments are based on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). PISA is developed under the auspices of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Note that the ISA is not part of PISA and is not endorsed by the OECD. What is ACER? ACER is one of the world's leading educational research centres, committed to creating and promoting research-based knowledge, products and services that can be used to improve learning across the life span. ACER has built a strong reputation as a reliable provider of support and expertise to education policy makers and professional practitioners since it was established in 1930. The development of the ISA is linked to ACER’s work on PISA: ACER led a consortium of research and educational institutions as the major contractor to deliver the PISA project on behalf of the OECD from 2000 to 2012. What is PISA? PISA is a triennial international survey which aims to evaluate education systems worldwide by testing the skills and knowledge of nationally representative samples of 15-year-old students in key subjects: reading literacy, mathematical literacy and scientific literacy in order to inform national stakeholders about how well their education systems are preparing young people for life after compulsory education. -

Handreichung Interkulturelle Bildung Und Erziehung

Senatsverwaltungfür Schule,JugendundSport Handreichung fürLehrkräfte anBerlinerSchulen BildungundErziehung 2 Impressum Herausgeber: Senatsverwaltung für Schule, Jugend und Sport Beuthstraße 6 - 8,10117 Berlin Telefon (030) 9026 111 Fax (030) 9026 5001 eMail: [email protected] Internet: www.sensjs.berlin.de Redaktion: Moritz Felgner (verantwortlich), Ulrike Grassau, Sabine Froese (Basistext) Gestaltung: ITpro Druck: Verwaltungsdruckerei Berlin, Kohlfurter Str. 41/43, 10999 Berlin Auflage: 10.000 Berlin, Juli 2001 Diese Broschüre ist Teil der Öffentlichkeitsarbeit des Landes Berlin. Sie ist nicht zum Verkauf bestimmt und darf nicht zur Werbung für politische Partei- en verwendet werden. 3 Interkulturelle Bildung und Erziehung - Inhalt INHALT Vorwort ..............................................................................................6 1. Einführung ................................................................................7 1.1 Aufbau und Ziel der Handreichung .............................................7 1.2 Die rechtlichen Grundlagen ........................................................9 Exkurse: • Begegnung mit dem Fremden .........................................................12 • Eigenes und Fremdes .....................................................................17 2. Interkulturelles Lernen ..........................................................22 2.1 Die Wahrnehmung anderer Kulturen ........................................24 2.2 Genese und Konzept interkulturellen Lernens ..........................28 -

Schulträgerbudget Typ-A Allgemeinbildende Gemäß 3.1

Anlage Zusatz1-Schulträgerbudget Typ-A Allgemeinbildende gemäß 3.1. Zusatz1-DigitalPakt-SifT Nr. Träger Schule BSN SuS mögliche Förderung mögliche Förderung Schulträger 1 Aktion Sonnenschein Berlin gGmbH Erste Aktivschule Charlottenburg (Grundschule) 04P22 49 2.815,05 € 2.815,05 € 2 Neue Freie Schule Pankow e.G. Freie Schule Pankow (Integrierte Sekundarschule) 03P13 109 6.262,05 € 6.262,05 € 3 Alternativschule Berlin e.V. Alternativschule Berlin (Gemeinschaftsschule) 12P11 123 7.066,35 € 7.066,35 € 4 Annie Heuser Schule e.V. Annie-Heuser-Schule 04P12 299 17.177,55 € 17.177,55 € 5 Berlin Bilingual School Pfefferwerk gGmbH Berlin Bilingual School (Grundschule) 02P11 291 16.717,95 € 23.267,25 € 6 Berlin Bilingual School Pfefferwerk gGmbH Berlin Bilingual School (Integrierte Sekundarschule) 03P37 114 6.549,30 € 7 Berlin British School gGmbH Berlin British School (Grundschule) 04P39 97 5.572,65 € 7.813,20 € 8 Berlin British School gGmbH Berlin British School (Integierte Sekundarschule) 04P40 39 2.240,55 € 9 Berlin Metropolitan School GmbH Berlin Metropolitan School (Integrierte Sekundarschule) 01P16 825 47.396,25 € 47.396,25 € 10 Berthold-Otto-Schule e.V. Gemeinschaftsschule nach der Pädagogik Berthold Ottos 06P13 164 9.421,80 € 9.421,80 € 11 BifiZ Bildung für eine intelligente Zukunft gemeinnützige GmbH Private Goethe-Schulen 12P07 193 11.087,85 € 11.087,85 € 12 BSB GmbH BEST-Sabel-Gemeinnützige Bildungsgesellschaft BEST-Sabel-Oberschule 09P09 291 16.717,95 € 13 BSB GmbH BEST-Sabel-Gemeinnützige Bildungsgesellschaft BEST-Sabel-Grundschule Kaulsdorf 10P13 343 19.705,35 € 56.703,15 € 14 BSB GmbH BEST-Sabel-Gemeinnützige Bildungsgesellschaft BEST-Sabel-Grundschule Mahlsdorf 10P05 353 20.279,85 € 15 Canisius-Kolleg GmbH Canisius-Kolleg (Gymnasium) 01P06 877 50.383,65 € 50.383,65 € 16 Caroline von Heydebrand-Heim e.V. -

Vereinbarung Über Die Anerkennung Des IB-Diploma

Vereinbarung über die Anerkennung des „International Baccalaureate Diploma/ Diplôme du Baccalauréat International“ ___________________________________________________________________ (Beschluss der Kultusministerkonferenz vom 10.03.1986 i. d. F. vom 26.11.2020) SEKRETARIAT DER KULTUSMINISTERKONFERENZ BERLIN · Taubenstraße 10 · 10117 Berlin · Postfach 11 03 42 · 10833 Berlin · Telefon +49 30 25418-499 BONN · Graurheindorfer Straße 157 · 53117 Bonn · Postfach 22 40 · 53012 Bonn · Telefon +49 228 501-0 Seite 2 1. Ein nach den Bestimmungen der/des "International Baccalaureate Organisation (IBO)/Office du Baccalauréat International" erworbenes "International Baccalau- reate Diploma/Diplôme du Baccalauréat International" wird als Hochschulzu- gangsqualifikation anerkannt, wenn es nach einem Besuch von mindestens zwölf aufsteigenden Jahrgangsstufen an Schulen mit Vollzeitunterricht erworben wor- den ist und die nachstehenden Bedingungen erfüllt sind: a) Unter den sechs Prüfungsfächern des "International Baccalaureate Dip- loma/Diplôme du Baccalauréat International" (IB) müssen folgende nach der Terminologie des IB bezeichnete Fächer sein: - zwei Sprachen auf dem Niveau A oder B (davon mindestens eine fort- gesetzte Fremdsprache als "Language A"1 oder „Language B HL“2), - ein naturwissenschaftliches Fach (Biology, Chemistry, Physics), - Mathematik (Mathematics: Analysis and Approaches3 oder Mathema- tics: Applications and Interpretation3)4, - ein gesellschaftswissenschaftliches Fach (History, Geography, Eco- nomics, Psychology, Philosophy, Social -

School Id Name Street Plz Ort Bezirk 1 Grundschule Am Arkonaplatz Ruppiner Str

school_id name street plz ort bezirk 1 Grundschule am Arkonaplatz Ruppiner Str. 10115 Berlin Mitte 2 Papageno‐Grundschule Bergstr. 10115 Berlin Mitte 4 Grundschule Neues Tor Hannoversche Str. 10115 Berlin Mitte 31 Grundschule am Koppenplatz Koppenplatz 10115 Berlin Mitte 36 Jüdisches Gymnasium Moses Mendelssohn Große Hamburger Str. 10115 Berlin Mitte 41 Berlin Metropolitan School (Integrierte Sekundarschule) Linienstr. 10115 Berlin Mitte 48 Musikgymnasium Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Rheinsberger Str. 10115 Berlin Mitte 6 Grundschule am Brandenburger Tor Wilhelmstr. 10117 Berlin Mitte 3 Kastanienbaum‐Grundschule Gipsstr. 10119 Berlin Mitte 43 Berlin Cosmopolitan School Rückerstr. 10119 Berlin Mitte 110 Grundschule am Teutoburger Platz Templiner Str. 10119 Berlin Pankow 35 Evangelische Schule Berlin Mitte (Gemeinschaftsschule) Rochstr. 10178 Berlin Mitte 37 Freie Waldorfschule Berlin Mitte Weinmeisterstr. 10178 Berlin Mitte 5 GutsMuths‐Grundschule Singerstr. 10179 Berlin Mitte 7 City‐Grundschule Sebastianstr. 10179 Berlin Mitte 55 Ludwig‐Hoffmann‐Grundschule Lasdehner Str. 10243 Berlin Friedrichshain‐Kreuzberg 79 Blumen‐Grundschule Andreasstr. 10243 Berlin Friedrichshain‐Kreuzberg 85 Kreativitätsschulzentrum Berlin gGmbH Strausberger Str. 10243 Berlin Friedrichshain‐Kreuzberg 86 Netzwerk‐Schule (Gemeinschaftsschule) Marchlewskistr. 10243 Berlin Friedrichshain‐Kreuzberg 88 Temple‐Grandin‐Schule Lasdehner Str. 10243 Berlin Friedrichshain‐Kreuzberg 89 Margarethe‐von‐Witzleben‐Schule Palisadenstr. 10243 Berlin Friedrichshain‐Kreuzberg 91 Andreas‐Gymnasium -

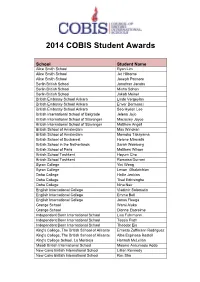

2014 COBIS Student Awards

2014 COBIS Student Awards School Student Name Alice Smith School Ryan Lim Alice Smith School Jet Hilborne Alice Smith School Joseph Patmore Berlin British School Jonathan Jacobs Berlin British School Misha Sohan Berlin British School Jakob Meinel British Embassy School Ankara Linde Vergeylan British Embassy School Ankara Enver Dermanci British Embassy School Ankara Seo Hyeon Lee British International School of Belgrade Jelena Jojic British International School of Stavanger Macauley Joyce British International School of Stavanger Matthew Angell British School of Amsterdam Max Winokan British School of Amsterdam Momoko Takayama British School of Bucharest Helene Miravalls British School in the Netherlands Sarah Weinberg British School of Paris Matthew Wilson British School Tashkent Hoyurn Cho British School Tashkent Romaisa Durrani Byron College Yini Weng Byron College Levon Ghalatchian Doha College Hollie Jenkins Doha College Tisal Edirisinghe Doha College Nina Nair English International College Vladimir Solomatin English International College Emma Bell English International College Jonas Fleega Grange School Wami Aluko Grange School Dionne Eboreime Independent Bonn International School Lisa Fuhrmann Independent Bonn International School Tassia Flath Independent Bonn International School Theodor Eis King's College, The British School of Alicante Ernesto Zoffmann Rodriguez King's College, The British School of Alicante Alba Espinosa Rastoll King's College School, La Moraleja Hannah McLellan Maadi British International School Maame Assumadu Addo New Cairo British International School Lillian Kennedy New Cairo British International School Kim Sha New Cairo British International School Georgina Bonney Olga Gudynn International School Vlad Asaftei Olga Gudynn International School Matei Manea Olga Gudynn International School Alexia Micheli Riverside School Ladislav Charouz Riverside School Vojtěch Smekal Riverside School Anna Zvagule Sir James Henderson British School of Milan Davide Ravaccia St. -

TEFL Contactscontacts Usefuluseful Informationinformation Andand Contactscontacts

TEFLTEFL ContactsContacts UsefulUseful informationinformation andand contactscontacts www.onlinetefl.comwww.onlinetefl.com 1000’s of job contacts – designed to help you find the job of your dreams You’ve done all the hard work, you’ve completed a TEFL course, you’ve studied for hours and now you’ll have to spend weeks trawling through 100’s of websites and job’s pages trying to find a decent job! But do not fear, dear reader, there is help at hand! We may have mentioned it before, but we’ve been doing this for years, so we’ve got thousands of job contacts around the world and one or two ideas on how you can get a decent teaching job overseas - without any of the hassle. Volunteer Teaching Placements Working as a volunteer teacher gives you much needed experience and will be a fantastic addition to your CV. We have placements in over 20 countries worldwide and your time and effort will make a real difference to the lives of your students. Paid Teaching Placements We’ll find you well-paid work in language schools across the world, we’ll even arrange accommodation and an end of contract bonus. Get in touch and let us do all the hard work for you. For more information, give us a call on: +44 (0)870 333 2332 –UK (Toll free) 1 800 985 4864 – USA +353 (0)58 40050 – Republic of Ireland +61 1300 556 997 – Australia Or visit www.i-to-i.com If you’re determined to find your own path, then our list of 1000’s of job contacts will give you all the information you’ll need to find the right job in the right location. -

8. Hans Soldan Moot in Hannover, 30.9. - 10.10.2020 Facebook | Für Die Anwälte Von Morgen

BUNDESWEITER MOOT COURT-WETTBEWERB FÜR STUDIERENDE DEUTSCHER JURAFAKULTÄTEN 8. Hans Soldan Moot in Hannover, 30.9. - 10.10.2020 facebook | für die Anwälte von morgen. Impressum Leibniz Universität Hannover Juristische Fakultät Lehrstuhl für Bürgerliches Recht, Deutsches, Europäisches und Internationales Zivilprozessrecht Professor Dr. Christian Wolf Königsworther Platz 1 30167 Hannover Seite 2 Geleitworte Präsident der Bundesrechtsanwaltskammer Präsidentin des Deutschen Anwaltvereins Vorsitzender des Deutschen Juristen-Fakultätentages Vorstand der Hans Soldan Stiftung Geschäftsführender Direktor des IPA Teams Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg I Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg II Bucerius Law School I Bucerius Law School II Bucerius Law School III Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel Freie Universität Berlin I Freie Universität Berlin II Friedrich-Alexander Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg Team I Friedrich-Alexander Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg Team II Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Team I Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Team II Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Team III Leibniz Universität Hannover Team I Leibniz Universität Hannover Team II Ruhr-Universität Bochum Universität Bayreuth Team I Universität Bayreuth Team II Universität Bayreuth Team III Univeristät Hamburg Team I Univeristät Hamburg Team II Univeristät Hamburg Team III Universität zu Köln I Universität zu Köln II Paarungen Konferenzprogramm Sprecher der Konferenz Praktiker als Richter und Juroren Preise des Soldan Moots Seite 3 GELEITWORTE Liebe Soldan-Moot-Teilnehmer, -

20Th November 2015 Dear Request for Information Under the Freedom

Governance & Legal Room 2.33 Services Franklin Wilkins Building 150 Stamford Street Information Management London and Compliance SE1 9NH Tel: 020 7848 7816 Email: [email protected] By email only to: 20th November 2015 Dear Request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (“the Act”) Further to your recent request for information held by King’s College London, I am writing to confirm that the requested information is held by the university. Some of the requested is being withheld in accordance with section 40 of the Act – Personal Information. Your request We received your information request on 26th October 2015 and have treated it as a request for information made under section 1(1) of the Act. You requested the following information. “Would it be possible for you provide me with a list of the schools that the 2015 intake of first year undergraduate students attended directly before joining the Kings College London? Ideally I would like this information as a csv, .xls or similar file. The information I require is: Column 1) the name of the school (plus any code that you use as a unique identifier) Column 2) the country where the school is located (ideally using the ISO 3166-1 country code) Column 3) the post code of the school (to help distinguish schools with similar names) Column 4) the total number of new students that joined Kings College in 2015 from the school. Please note: I only want the name of the school. This request for information does not include any data covered by the Data Protection Act 1998.” Our response Please see the attached spreadsheet which contains the information you have requested. -

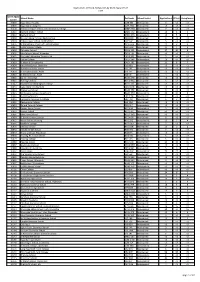

2017 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2017 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 7 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 13 6 5 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 5 5 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 5 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 11 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 17 4 3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 10 8 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 5 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 21 8 7 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 4 <3 <3 10040 Garth Hill College RG42 2AD Maintained <3 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 3 <3 <3 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained 3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU -

ISA 2013–14 Participating Schools

ISA 2013–14 Participating Schools Over 70 000 students from 333 schools participated in ISA 2013-14. The following 296 schools have given permission for their school's name to be published by ACER for information, general reporting, and/or publicity purposes. ASIA SINGAPORE German European School Singapore UNITED KINGDOM ACS Egham International School AZERBAIJAN The International School of Azerbaijan ISS International School International Community School BANGLADESH International School Dhaka One World International School International School of Aberdeen CAMBODIA Hope International School SOUTH KOREA Busan International Foreign School Marymount International School, London International School of Phnom Penh Dwight School Seoul Southbank International School, Northbridge International School Cambodia Gyeonggi Suwon International School Hampstead CHINA Access International Academy Ningbo Hyundai Foreign School Southbank International School, Beijing City International School Seoul International School Kensington Beijing World Youth Academy Taejon Christian International School Southbank International School , Canadian International School of Beijing SRI LANKA The Overseas School of Colombo Westminster Chengdu International School THAILAND Chiang Mai International School The International School of Azerbaijan Daystar Academy Concordian International School The King Fahad Academy Etonhouse International School Wuxi Gecko School Guangzhou Nanhu International School Heathfield International School Hua Mao Multicultural Education Academy International -

Athletics-ASAP-Brochure-2021-2022

After School Sports & Activities Program ISS After School Sports & Activities Program Dear ISS Students and Parents, Participation in the After School Sports and Activities Program will add a level of responsibility and commitment, but also fun, to both academic and social life. It will challenge you as a student and will foster an attitude of positive participation. We hope this booklet will help you understand the expectations involved in becoming a member of one of our programs. We at the International School of Stuttgart e.V. (ISS) wish this experience to be as satisfying as possible for both students and parents. Sincerely, Radi Zdravkovic, Athletics Director Our Mission The Goal of the ISS After School Sports and Activities Program is to provide and coordinate a variety of competitive, noncompetitive and recreational activities for our students to further develop physical, social and interpersonal abilities. The program enhances the ISS experience, promotes our school’s identity and helps to prepare our students for future challenges. The International School of Stuttgart e.V. is a global and international school community that gives its students opportunities to grow in many different ways. Learning is always at the heart of all we do. However, learning can happen in many places, not just inside the classroom. It is for this reason that we try to offer a wide variety of activities for all students, in sports and many other different activities. We always hope that as many students as possible take advantage of these opportunities. INSPIRE. CHALLENGE. SUPPORT. 3 GISST ISS is a member of the German International School Sports Tournaments league (GISST).