Local Democracy and Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT – RC 6 Religion, Faith and the Craft: Social Practices In

ABSTRACT – RC 6 Religion, Faith and the Craft: Social Practices in Dealing with Life Crisis Dr. Anannya Gogoi Assistant Professor Department of Sociology Dibrugarh University Phone: 9435057396 Email: [email protected] LMI - 3198 Abstract: Social Anthropology and Social Psychology have fruitfully attempted to observe and interpret the relationship and interdependency between religion on the one hand and the community and society on the other. Emile Durkheim, James Frazer, Bronislaw Malinowski and Carl Jung are the few names that have contributed immensely to the study of the role of religion in shaping the belief systems of people in a given society. In different social context the definition and the significance of religion have varied. Nevertheless religion as a system of belief has always been an important social institution. However science and rationality are often considered polar opposite of a few of these belief systems and faith in the modern society. The rising visibility of incidences of witchcraft and ‘black magic’ in the North Easternstates of India as well as other societies has posed a challenge in bringing social order and spreading modern education and literacy. The current discussion is a narrative of certain practices such as magic, witchcraft, faith healing and counseling in religious tenets that are followed by the people during crisis. The paper tries to look at these practices from a socio- psychological approach. I would 1 like to do thisby narrating and interpreting the practices and their significance as a system of belief and faith. The Changing Gender roles in early Christianity Melissa. C. Remedios M.Phil Christ University Bangalore Email: [email protected] Membership: Awaited Abstract: The paper intends to study how religion influences women in their gender makeup and the roles they played in the larger society. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

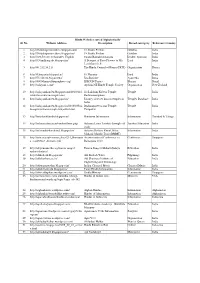

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

CAMEO Conflict and Mediation Event Observations Event and Actor Codebook

CAMEO Conflict and Mediation Event Observations Event and Actor Codebook Event Data Project Department of Political Science Pennsylvania State University Pond Laboratory University Park, PA 16802 http://eventdata.psu.edu/ Philip A. Schrodt (Project Director): < schrodt@psu:edu > (+1)814.863.8978 Version: 1.1b3 March 2012 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.0.1 Events . .1 1.0.2 Actors . .4 2 VERB CODEBOOK 6 2.1 MAKE PUBLIC STATEMENT . .6 2.2 APPEAL . .9 2.3 EXPRESS INTENT TO COOPERATE . 18 2.4 CONSULT . 28 2.5 ENGAGE IN DIPLOMATIC COOPERATION . 31 2.6 ENGAGE IN MATERIAL COOPERATION . 33 2.7 PROVIDE AID . 35 2.8 YIELD . 37 2.9 INVESTIGATE . 43 2.10 DEMAND . 45 2.11 DISAPPROVE . 52 2.12 REJECT . 55 2.13 THREATEN . 61 2.14 PROTEST . 66 2.15 EXHIBIT MILITARY POSTURE . 73 2.16 REDUCE RELATIONS . 74 2.17 COERCE . 77 2.18 ASSAULT . 80 2.19 FIGHT . 84 2.20 ENGAGE IN UNCONVENTIONAL MASS VIOLENCE . 87 3 ACTOR CODEBOOK 89 3.1 HIERARCHICAL RULES OF CODING . 90 3.1.1 Domestic or International? . 91 3.1.2 Domestic Region . 91 3.1.3 Primary Role Code . 91 3.1.4 Party or Speciality (Primary Role Code) . 94 3.1.5 Ethnicity and Religion . 94 3.1.6 Secondary Role Code (and/or Tertiary) . 94 3.1.7 Specialty (Secondary Role Code) . 95 3.1.8 Organization Code . 95 3.1.9 International Codes . 95 i CONTENTS ii 3.2 OTHER RULES AND FORMATS . 102 3.2.1 Date Restrictions . 102 3.2.2 Actors and Agents . -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Internationale Gesellschaft Hegel-Marx

Materialismo Storico, n° 2/2020 (vol. IX) Notes towards a Gramscian analysis of a pandemic year in India Karin Kapadia (University of Oxford) In 2020 the authoritarian Hindu-supremacist BJP party was in its second term. With Modi leading it, the party won a landslide in 2019 and a majority in Parliament. Modi and the BJP were relatively restrained in their first term, however in their second term they vigorously implemented their coercive agenda and their ultra-neoliberal program of total deregulation and privatization. They were assisted by the Covid-19 pandemic which became their universal excuse for (1) shutting down political prote- sts, (2) rushing through laws attacking workers, farmers and the rights of women, (they had passed laws attacking Muslims in 2019) and (3) arresting lawyers, trade unionists, journalists, university students, grassroots organizers, and organizers/leaders of subaltern groups, especially Dalits and Adivasis, on terrorism charges, denying them bail or trial. Modi and the BJP are using shock- doctrine-tactics to frighten the public and to blame Muslims for the virus. They have been successful because they control the media. Astonishingly, even though the government did shockingly little to help the starving millions who lost their jobs, the government has not lost its popularity. Its passive revolution strategies and its amazingly firm hegemonic power are examined within this conjuncture: a new neoliberal form of Hinduism is flourishing today. Dissent; Labour; Authoritarianism; Shock-doctrine; Hegemony. 1. The neoliberal conjuncture and an elitist political takeover1 1.1. Intensifying nationalisms, racisms, and populist politics in the neoliberal era Great thinkers have special insights that make their reflections valuable to after-times. -

E Sangh Parivar

Shadow Armies Fringe Organizations and Foot Soldiers of Hindutva Dhirendra K. Jha JUGGERNAUT BOOKS KS House, 118 Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110049, India First published in hardback by Juggernaut Books 2017 Published in paperback 2019 Copyright © Dhirendra K. Jha 2017 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher. e views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own. e facts contained herein were reported to be true as on the date of publication by the author to the publishers of the book, and the publishers are not in any way liable for their accuracy or veracity. ISBN 9789353450199 Typeset in Adobe Caslon Pro by R. Ajith Kumar, New Delhi Printed at Manipal Technologies Ltd, India Contents Introduction 1. Sanatan Sanstha 2. Hindu Yuva Vahini 3. Bajrang Dal 4. Sri Ram Sene 5. Hindu Aikya Vedi 6. Abhinav Bharat 7. Bhonsala Military School 8. Rashtriya Sikh Sangat Notes Acknowledgements A Note on the Author Introduction India has seen astonishing growth in the politics of Hindutva over the last three decades. Several strands of this brand of politics – not just the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) but also those working for it in the shadows – have shot into prominence. ey are all fuelled by a single motive: to ensure that one particular community, the Hindus, has the exclusive right to define our national identity. e Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a pan-Indian organization comprising chauvinistic Hindu men, is the vanguard of this politics. -

SNDP – RSS – SIMI – Maldives

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND33857 Country: India Date: 22 October 2008 Keywords: India – Kerala – SNDP – RSS – SIMI – Maldives This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide advice on any attacks on SNDP members since 2003 in Kerala. 2. Please advise of any attacks of the RSS on the Hindu population in Kerala. 3. Please advise if there is any information on a bomb attack in Mala or Male in 2007 conducted by a Hindu fanatic? 4. Please advise of the level of police protection in Kerala against attacks by RSS and SIMI and whether they are supporters of religious fanatics. 5. Please advise whether the judiciary is effective in Kerala against such attacks by organisations such as SIMI and the RSS. 6. Please provide details about SIMI and their aims and whether they are in operation in Kerala. RESPONSE 1. Please provide advice on any attacks on SNDP members since 2003 in Kerala. No information could be located on a movement with the exact title of “Sree Narayana Paripalana Sabha”. Extensive information is available on the Kerala SNDP movement known as the Sri Narayana Dharma Paripalana (SNDP; Society for the Preservation of Sree Narayana Guru’s Moral Path; also: Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana). -

News & World Capsule Ugmc Group2-14

NEWS & WORLD NEW DELHI, INDIA WEEK OF DECEMBER, 14-21, 2015 www.mediacenterimac.com INDIA’S FAVOURITE NEWSPAPER Vol.1 No.02 Sonia and Rahul are free First Kejriwal, Now kirti for now attacks Jaitely, BJP RONIKA RATRA. NEW DELHI calls him fake Congress president Sonia Gandhi and Vice President Rahul Gandhi were VISHAKHA BHAGAT, NEW DELHI summoned to the court for the National BJP MP Kirti Azad targeted his own party Herald case and got bail within 15 member Arun Jaitely in a press minutes . However they have to come conference on Sunday imposing on him th back to the court on 20 february. the allegation of irregularities in DDCA This case is about Sonia Gandhi along (Delhi District Cricket Association.) with six other people who illegally The whole case started when a CBI raid captured National Herald’s property. happened at Delhi’s CM Arvind Kejriwal Other than Sonia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi, office and he accused Arun Jaitely in Motilal Vohra, Oscar Fernandes, Sam defence.After this Kirti Azad BJP MP Pitroda and Suman Dubey were a part of and a former Indian Cricket player came this case. Sonia Gandhi along with other up with 52 questions to the ministers members were given bail without any though he didn’t named Jaitely. However, BJP came in a support of Jaitely.”We are conditions opposed on them. Sonia’s bail proud of impeccable Qualities of honesty, was given by A K Antony and Rahul’s integrity and credibility of Arun Jaitely”, bail was given by Priyanka Vadra. Now said Ravi Shanker Prasad, Union Minister. -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. No. Reference Broad catergory Website Address Description Country 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/m Hindu Kush odern/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temp Hindu Temples of Kabul les_of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?modul Hindu Temples of Afaganistan e=pluspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint &title=Hindu%20Temples%20in%20Afg hanistan%20.html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of