IND34701 Country: India Date: 1 May 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT – RC 6 Religion, Faith and the Craft: Social Practices In

ABSTRACT – RC 6 Religion, Faith and the Craft: Social Practices in Dealing with Life Crisis Dr. Anannya Gogoi Assistant Professor Department of Sociology Dibrugarh University Phone: 9435057396 Email: [email protected] LMI - 3198 Abstract: Social Anthropology and Social Psychology have fruitfully attempted to observe and interpret the relationship and interdependency between religion on the one hand and the community and society on the other. Emile Durkheim, James Frazer, Bronislaw Malinowski and Carl Jung are the few names that have contributed immensely to the study of the role of religion in shaping the belief systems of people in a given society. In different social context the definition and the significance of religion have varied. Nevertheless religion as a system of belief has always been an important social institution. However science and rationality are often considered polar opposite of a few of these belief systems and faith in the modern society. The rising visibility of incidences of witchcraft and ‘black magic’ in the North Easternstates of India as well as other societies has posed a challenge in bringing social order and spreading modern education and literacy. The current discussion is a narrative of certain practices such as magic, witchcraft, faith healing and counseling in religious tenets that are followed by the people during crisis. The paper tries to look at these practices from a socio- psychological approach. I would 1 like to do thisby narrating and interpreting the practices and their significance as a system of belief and faith. The Changing Gender roles in early Christianity Melissa. C. Remedios M.Phil Christ University Bangalore Email: [email protected] Membership: Awaited Abstract: The paper intends to study how religion influences women in their gender makeup and the roles they played in the larger society. -

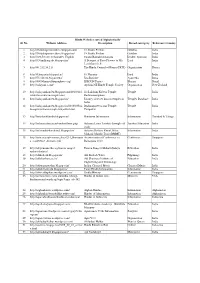

Janakeeya Hotel Updation 07.09.2020

LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Home No. of Sl. Rural / No Of Parcel By Sponsored by District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Initiative Delivery units No. Urban Members Unit LSGI's (Sept 7th ) (Sept 7th ) (Sept 7th) Janakeeya 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI church, Kodukulanji Rural 5 32 0 0 Hotel Coir Machine Manufacturing Janakeeya 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Ruchikoottu Janakiya Bhakshanasala Urban 4 194 0 15 Company Hotel Janakeeya 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Samrudhi janakeeya bhakshanashala Pazhaveedu Urban 5 137 220 0 Hotel Janakeeya 4 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 0 60 5 Hotel Janakeeya 5 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 112 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 6 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 63 12 10 Hotel Janakeeya 7 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Sasneham Janakeeya Hotel Koyickal chantha Rural 5 73 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 8 Alappuzha Budhanoor sampoorna mooshari parampil building Rural 5 10 0 0 Hotel chengannur market building Janakeeya 9 Alappuzha Chenganoor SRAMADANAM Urban 5 70 0 0 complex Hotel Chennam pallipuram Janakeeya 10 Alappuzha Chennam Pallippuram Friends Rural 3 0 55 0 panchayath Hotel Janakeeya 11 Alappuzha Cheppad Sreebhadra catering unit Choondupalaka junction Rural 3 63 0 0 Hotel Near GOLDEN PALACE Janakeeya 12 Alappuzha Cheriyanad DARSANA Rural 5 110 0 0 AUDITORIUM Hotel Janakeeya 13 Alappuzha Cherthala Municipality NULM canteen Cherthala Municipality Urban 5 90 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 14 Alappuzha Cherthala Municipality Santwanam Ward 10 Urban 5 212 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 15 Alappuzha Cherthala South Kashinandana Cherthala S Rural 10 18 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 16 Alappuzha Chingoli souhridam unit karthikappally l p school Rural 3 163 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 17 Alappuzha Chunakkara Vanitha Canteen Chunakkara Rural 3 0 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 18 Alappuzha Ezhupunna Neethipeedam Eramalloor Rural 8 0 0 4 Hotel Janakeeya 19 Alappuzha Harippad Swad A private Hotel's Kitchen Urban 4 0 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 20 Alappuzha Kainakary Sivakashi Near Panchayath Rural 5 0 0 0 Hotel 43 LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Home No. -

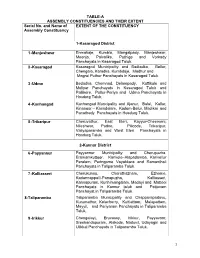

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Impact of Resettlement on Scheduled Tribes in Kerala: a Study on Aralam Farm

Impact of Resettlement on Scheduled Tribes in Kerala: A study on Aralam Farm A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Sociology by Deepa Sebastian (Reg. No.1434502) Under the Guidance of Sudhansubala Sahu Assistant Professor Department of Sociology CHRIST UNIVERSITY BENGALURU, INDIA December 2016 APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Dissertation entitled ‘Impact of Resettlement on Scheduled Tribes in Kerala: A Study on Aralam Farm’ b y Deepa Sebastian Reg. No. 1434502 is approved for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in Sociology. Examiners: 1. 2. Supervisor: ___________________ ___________________ Chairman: ___________________ ___________________ Date: Place: Bengaluru ii DECLARATION I Deepa Sebastian hereby declare that the dissertation, titled ‘Impact of Resettlement on Scheduled Tribes in Kerala: A Study on Aralam Farm’ is a record of original research work undertaken by me for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in Sociology. I have completed this study under the supervision of Dr Sudhansubala Sahu, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology. I also declare that this dissertation has not been submitted for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship or other title. It has not been sent for any publication or presentation purpose. I hereby confirm the originality of the work and that there is no plagiarism in any part of the dissertation. Place: Bengaluru Date: Deepa Sebastian Reg. No.1434502 Department of Sociology Christ University, Bengaluru iii CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation submitted by Deepa Sebastian (1434502 ) titl ed ‘Impact of Resettlement on Scheduled Tribes in Kerala: A Study on Aralam Farm’ is a record of research work done by her during the academic year 2014-2016 under my supervision in partial fulfillment for the award of Master of Philosophy in Sociology. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Challenges Before Kerala's Landless: the Story of Aralam Farm

SPECIAL ARTICLE Challenges before Kerala’s Landless: The Story of Aralam Farm M S Sreerekha Whether from a class perspective or from a community truggles waged by the landless at Muthanga, Chengara identity perspective, it is undeniably the biggest failure and elsewhere for more than a decade indicate how that decades after the land reforms, a good majority of SK erala’s much-fl aunted history of land reforms is becom- ing increasingly questionable. For the adivasi community, the the dalits and adivasis in Kerala remain fully landless. In struggle has been essentially about the restoration of their alien- the context of the Supreme Court verdict of 21 July 2009, ated land. Every piece of law enacted towards this has failed or which rejected a stay order by the Kerala High Court on made to fail; the passing of the Kerala Restriction on Transfer by important sections of the Kerala Restriction on Transfer and Restoration of Lands to Scheduled Tribes Act, 1999 by the state assembly was yet another blow. The Supreme Court verdict by and Restoration of Lands to Scheduled Tribes Act, on 21 July 2009 rejected a stay order by the Kerala High Court on 1999 and the new scenario where the legislature and the important sections of this act. This verdict has validated the 1999 judiciary proclaim that the adivasi community has now Act. For the adivasi population of around 3.21 lakh (of which 80% agreed for alternate land, and therefore, the issue of are landless), as far as restoration of their alienated land is con- cerned, this judgment is a battle lost legally. -

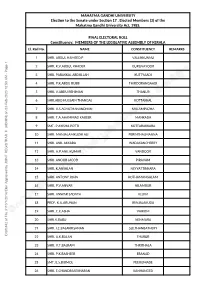

MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY Election to The

MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY Election to the Senate under Section 17 , Elected Members (3) of the Mahatma Gandhi University Act, 1985. FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL Constituency: MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF KERALA El. Roll No. NAME CONSTITUENCY REMARKS 1 SHRI. ABDUL HAMEED.P VALLIKKUNNU 2 SHRI. K.V.ABDUL KHADER GURUVAYOOR 3 SHRI. PARAKKAL ABDULLAH KUTTYAADI 4 SHRI. P.K.ABDU RUBB THIROORANGAADI 5 SHRI. V.ABDU REHIMAN THANUR 6 SHRI.ABID HUSSAIN THANGAL KOTTAKKAL 7 SHRI. V.S ACHUTHANANDHAN MALAMPUZHA 8 SHRI. T.A.AHAMMAD KABEER MANKADA 9 SMT. P AYISHA POTTI KOTTARAKKARA 10 SHRI. MANJALAMKUZHI ALI PERINTHALMANNA 11 SHRI. ANIL AKKARA WADAKANCHERRY 12 SHRI. A.P.ANIL KUMAR VANDOOR 13 SHRI. ANOOB JACOB PIRAVAM 14 SHRI. K.ANSALAN NEYYATTINKARA 15 SHRI. ANTONY JOHN KOTHAMANGALAM 16 SHRI. P.V.ANVAR NILAMBUR 17 SHRI. ANWAR SADATH ALUVA 18 PROF. K.U.ARUNAN IRINJALAKUDA 19 SHRI. C.K.ASHA VAIKOM 20 SHRI.K.BABU NENMARA 21 SHRI. I.C.BALAKRISHNAN SULTHANBATHERY Draft #42 of File 3110/1/2014/Elen Approved by JOINT REGISTRAR II (ADMIN) on 03-Feb-2020 10:50 AM - Page 1 22 SHRI. A.K.BALAN THARUR 23 SHRI. V.T.BALRAM THRITHALA 24 SHRI. P.K.BASHEER ERANAD 25 SMT. E.S.BIJIMOL PEERUMADE 26 SHRI. E.CHANDRASEKHARAN KANHANGED 27 SHRI. K.DASAN QUILANDY 28 SHRI. B.D DEVASSY CHALAKUDI 29 SHRI. C.DIVAKARAN NEDUMANGAD 30 SHRI. V.K.IBRAHIM KUNJU KALAMASSERY 31 SHRI. ELDO ABRAHAM MUVATTUPUZHA 32 SHRI. ELDOSE P KANNAPPILLIL PERUMBAVOOR 33 SHRI. K.B.GANESH KUMAR PATHANAPURAM 34 SMT. GEETHA GOPI NATTIKA 35 SHRI. GEORGE M THOMAS THIRUVAMBADI 36 SHRI. -

Janakeeya Hotel Updation 02.11.2020

LUNCH LUNCH Parcel LUNCH Home Sponsored by No. of By Unit Delivery Sl. No. District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Rural / Urban No Of Members Initiative LSGI's units (November (November 2 (November 2 2nd) nd) nd) 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI church, Kodukulanji Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Ruchikoottu Janakiya Bhakshanasala Coir Machine Manufacturing Company Urban 4 Janakeeya Hotel 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Samrudhi janakeeya bhakshanashala Pazhaveedu Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 4 Alappuzha Ambalppuzha North Swaruma Neerkkunnam Rural 10 Janakeeya Hotel 5 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 6 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 Janakeeya Hotel 7 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 8 Alappuzha Aroor Navaruchi Vyasa charitable trust Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 9 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Sasneham Janakeeya Hotel Koyickal chantha Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 10 Alappuzha Budhanoor sampoorna mooshari parampil building Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 11 Alappuzha Chambakulam Jyothis Near party office Rural 4 Janakeeya Hotel 12 Alappuzha Chenganoor SRAMADANAM chengannur market building complex Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 13 Alappuzha Chennam Pallippuram Friends Chennam pallipuram panchayath Rural 3 Janakeeya Hotel 14 Alappuzha Chennithala Bhakshana sree canteen Chennithala Town Rural 4 Janakeeya Hotel 15 Alappuzha Cheppad Sreebhadra catering unit Choondupalaka junction Rural 3 Janakeeya Hotel 16 Alappuzha Cheriyanad DARSANA Near -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Documentation Kerala

DDOOCCUUMMEENNTTAATTIIOONN KKEERRAALLAA An index to articles in journals/periodicals available in the Legislature Library Vol. 11 (1) January – March 2016 SECRETARIAT OF THE KERALA LEGISLATURE THIRUVANANTHAPURAM DOCUMENTATION KERALA An index to articles in journals/periodicals available in the Legislature Library Vol.11 (1) January - March 2016 Compiled by G. Maryleela, Chief Librarian V. Lekha, Librarian Preetha Rani K.R., Deputy Librarian Hima.P.R, Catalogue Assistant Type setting Sunitha V.S BapJw \nbak`m sse{_dnbn e`yamb {][m\s¸« B\pImenI {]kn²oIcW§fn h¶n-«pÅ teJ-\-§-fn \n¶pw kmamPnIÀ¡v {]tbmP\{]Zhpw ImenI {]m[m\yapÅXpambh sXc-sª-Sp¯v X¿m-dm-¡nb Hcp kqNnIbmWv ""tUm¡psatâj³ tIcf'' F¶ ss{Xamk {]kn²oIcWw. aebmf `mjbnepw Cw¥ojnepapÅ teJ\§fpsS kqNnI hnjbmSnØm\¯n c−v `mK§fmbn DÄs¸Sp¯nbn«p−v. Cw¥ojv A£camem {Ia¯n {]tXyI "hnjbkqNnI' aq¶mw `mK¯pw tNÀ¯n«p−v. \nbak`m kmamPnIÀ¡v hnhn[ hnjb§fn IqSp-X At\z-jWw \S-¯m³ Cu "teJ\kqNnI' klmbIcamIpsa¶v IcpXp¶p. Cu {]kn²oIcWs¯¡pdn¨pÅ kmamPnIcpsS A`n{]mb§fpw \nÀt±i§fpw kzm-KXw sN¿p¶p. ]n. Un. imcw-K-[-c³ sk{I«dn tIcf \nbak`. CONT ENTS Pages Malayalam Section 01-40 English Section 41-51 Index 52-76 PART I MALAYALAM Accident 5. ]¨-¡dn X«n¸v tImbm-ap-Ip-¶¯v tIc-f-i-_vZw, 3 P\p-hcn 2016, t]Pv 38þ40 1. hml\ A]-I-S-§Ä Ipd-bv¡m³ am\-´-hmSn t»m¡v 2013þ14 km¼-¯nI hÀjw AUz. kt´mjv F.-F³ \S-¸m-¡nb Xncp-hm-Xnc ka-{K-]-¨-¡dn Irjn Nn´, 5 s^{_p-hcn 2016, t]Pv 35þ39 \S-¯n-¸p-ambn _Ô-s¸«v Agn-aXn \S-¶-Xmbn hÀ²n-¨p-h-cp¶ tdmU-]-I-S-§Ä Ipd-bv¡p-¶-Xn\v PnÃm-[-\-Imcy ]cn-tim-[-\-hn-`mKw Is−-¯n-b- Bh-iy-amb aps¶m-cp-¡-§-sf-¡p-dn¨v Xn-s\-¡p-dn-¨pÅ teJ-\w. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore