State and Society in Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Socio-Economic Underpinnings of Vaikam Sathyagraha in Travancore

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Colonialism, Social Reform and Social Change : The Socio-Economic underpinnings of Vaikam Sathyagraha in Travancore Dr. Subhash. S Asst. Professor Department of History Government College , Nedumangadu Thiruvanathapuram, Kerala. Abstract Vaikam Sathyagraha was a notable historical event in the history of Travancore. It was a part of antiuntouchability agitation initiated by Indian National Congress in 1924. In Travancore the Sathyagraha was led by T.K.Madhavan. Various historical factors influenced the Sathyagraha. The social structure of Travancore was organised on the basis of cast prejudices and obnoxious caste practices. The feudal economic system emerged in the medieval period was the base of such a society. The colonial penetration and the expansion of capitalism destroyed feudalism in Travancore. The change in the structure of economy naturally changed the social structure. It was in this context so many social and political movements emerged in Travancore. One of the most important social movements was Vaikam Sathyagraha. The British introduced free trade and plantations in Travancore by the second half of nineteenth century. Though it helped the British Government to exploit the economy of Travancore, it gave employment opportunity to so many people who belonged to Avarna caste. More over lower castes like the Ezhavas,Shannars etc. economically empowered through trade and commerce during this period. These economically empowered people were denied of basic rights like education, mobility, employment in public service etc. So they started social movements. A number of social movements emerged in Travancore in the nineteenth century and the first half of twentieth century. -

{A.Ffi Proceedings of the District Collector & District Magistarte Ldukki (Issued Under Section 21 of Crpc Tg73) (Preseng: H Dinesha N TAS)

/" {a.ffi Proceedings of the District Collector & District Magistarte ldukki (issued under Section 21 of CrPC tg73) (Preseng: H Dinesha n TAS) Sub : Disaster Manasement - Covid 19 Pandemic - Imminent / Possible surge - Effective Containment - Reinvigorating enforcement - Appointing Gazetted Officers of various Departments as Sectoral Magistarte & Covid Sentinels in local bodles - Order issued. Read: 1. GO (Rt) No 768/2020/DMD dated 29.09.2020 of Disaster Management (A) Department 2. GO (R0 No 77412020/DMD ated 01.10.2020 of Disaster Management (A) Department Proceedings No. DCIDIV 1640/2020- DM1 Dated : 04.10.2020 In the light of the surge in number of Covid 19 cases in the State, Government have decided to reinvigorate enforcement at the level of local bodies to check the surge in positive cases. Vide Order (2) above District Magistrates are directed to assess the ground situation in tleir districts and use the relevent provisions and orders under section 144, CrPC to control the spread of the desease. It was also directed that strict restrictions shall be imposed in the containment zones and in specific areas where the spread of desease is apprehended. Vide Order (1) cited, the Government ordered that the DDMA's shall depute Exclusively one or more, able Gazetted Officers from other departments of the State government (Deparments other than Health, Police, Revenue and LSGD) working in the District as Sectoral Magistrates & Covid Sentinels, in each local body who shall be tasked to reinvigorate monitoring and enforcement of Covid containment activities in their Jurisdiction. In the above circumstances, I, H Dineshan IAS, the District Magistrate and District Collector Idukki, by virtue of the powers conffened on me under the Disaster Management Act 2005, here by appoint and empower the following officers as Sector officers to monitor and enforce ali Covid Containment measures - existing and those introduced from time to time in their areas of jurisdisction specified by DDMA. -

The 123 Meeting of the SEAC KERALA Was Held Online During 27

MINUTES OF THE 123rd MEETING OF THE SEAC KERALA HELD DURING 27th – 30th JULY 2021 AT THE CONFERENCE HALL, STATE ENVIRONMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM The 123rd meeting of the SEAC KERALA was held online during 27th – 30th July, 2021 observing all the Covid-19 protocols stipulated by the Government. The meeting started at 10.00 AM on 27th July, 2021 with Dr.C. Bhaskaran, Chairman, SEAC KERALA chairing. The Chairman welcomed the members to the meeting. The Committee then moved on to the deliberations on the agenda items. PHYSICAL FILES Item No. 123. 01 Minutes of the 122nd SEAC meeting held on 15th – 18th June 2021 Decision: Noted. The Committee also ratified the decisions of the Chairman with respect to the changes in the Field Inspection Teams and nominations to the Joint Inspection Committees. Item No.123.02 Environmental Clearance for Granite building Stone Quarry in Sy. Nos. 464/2A, 464/2B/1, 464/1A/1,462/1A/2, 463/3B, 464/3/2 and 464/3/1 in Thirumarady Village, Muvattupuha Taluk, Ernakulam District - Judgment in WP (C) 7697/2021 (J) filed by Smt. Bindhu P.A.,Thevarmadom Granites -Revalidation of EC (File No. 997/EC3/4906/2015) Decision: The proponent and the RQP were present. The RQP made the presentation. The Committee entrusted Sri.K.Krishna Panicker and Dr.N. Ajith Kumar with the field inspection. Item No. 123.03 Judgment in WP (C) 3721/2021 filed by Sri.C.P.Muhammed- regarding the validity of EC. (File No.748/EC4/2021/SEIAA) Decision: The proponent’s authorised representative and the RQP were present. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Marxist Praxis: Communist Experience in Kerala: 1957-2011

MARXIST PRAXIS: COMMUNIST EXPERIENCE IN KERALA: 1957-2011 E.K. SANTHA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737102 November 2016 To my Amma & Achan... ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the outset, let me express my deep gratitude to Dr. Vijay Kumar Thangellapali for his guidance and supervision of my thesis. I acknowledge the help rendered by the staff of various libraries- Archives on Contemporary History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, C. Achutha Menon Study and Research Centre, Appan Thampuran Smaraka Vayanasala, AKG Centre for Research and Studies, and C Unniraja Smaraka Library. I express my gratitude to the staff at The Hindu archives and Vibha in particular for her immense help. I express my gratitude to people – belong to various shades of the Left - who shared their experience that gave me a lot of insights. I also acknowledge my long association with my teachers at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur and my friends there. I express my gratitude to my friends, Deep, Granthana, Kachyo, Manu, Noorbanu, Rajworshi and Samten for sharing their thoughts and for being with me in difficult times. I specially thank Ugen for his kindness and he was always there to help; and Biplove for taking the trouble of going through the draft intensely and giving valuable comments. I thank my friends in the M.A. History (batch 2015-17) and MPhil/PhD scholars at the History Department, S.U for the fun we had together, notwithstanding the generation gap. I express my deep gratitude to my mother P.B. -

1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 GENERAL River Periyar, the Longest of All the Rivers in the State of Kerala and Also the Largest in Poten

Pre Feasibility Report Page 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 GENERAL River Periyar, the longest of all the rivers in the State of Kerala and also the largest in potential, having a length of 244 km originates in the Sivagiri group of hills at an elevation of about +1830 m above MSL. This river basin is the second largest basin of Kerala State with a drainage area of 5398 Sq Km of which 114 sq km in the Anamalai fold lies in the State of Tamil Nadu. The Periyar Basin lies between 090 15’ N to 100 20’ N and longitude 760 10’ E to 770 30’E. From its origin, Periyar traverses through an immense cliff of rocks in a northerly direction receiving several streamlets in its course. About 48 km downstream, the Mullayar joins the main river at an elevation of +854 m above MSL. Afterwards, the river flows westwards and at about 11 km downstream of the confluence of Mullayar and Periyar, the river passes through a narrow gorge, where the present Mullaperiyar Dam is constructed in 1895. The name Mullaperiyar is derived from a portmanteau of Mullayar and Periyar. Below the Mullaperiyar Dam, the river flows in a winding course taking a north westerly direction. On its travel down, it is enriched by many tributaries like Kattappana Ar, Cheruthoni Ar, Perinjankutty Ar, Muthirapuzha Ar and Idamala Ar. Lower down of Malayatoor; the Pre Feasibility Report Page 2 river takes a meandering course and flows calmly and majestically for about 23 km through Kalady and Chowara and reaches Alwaye. -

MEDIA Handbook 2018

MEDIA hAnDbook 2018 Information & Public Relations Department Government of Kerala PERSONAL MEMORANDA Name................................................................................... Address Office Residence .......................... ............................... .......................... ............................... .......................... ............................... .......................... ............................... .......................... ............................... MEDIA HANDBOOK 2018 .......................... ............................... Information & Public Relations Department .......................... ............................... Government of Kerala Telephone No. Office ............................................... Chief Editor T V Subhash IAS Mobile ............................................... Co-ordinating Editor P Vinod Fax ............................................... Deputy Chief Editor K P Saritha E-mail ............................................... Editor Manoj K. Puthiyavila Residence ............................................. Editorial assistance Priyanka K K Nithin Immanuel Vehicle No .......................................................................... Gautham Krishna S Driving Licence No .............................................................. Ananthan R M Expires on . .......................................................................... Designer Ratheesh Kumar R Accreditation Card No ........................ Date....................... Circulation -

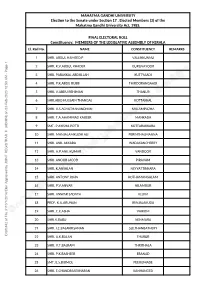

MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY Election to The

MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY Election to the Senate under Section 17 , Elected Members (3) of the Mahatma Gandhi University Act, 1985. FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL Constituency: MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF KERALA El. Roll No. NAME CONSTITUENCY REMARKS 1 SHRI. ABDUL HAMEED.P VALLIKKUNNU 2 SHRI. K.V.ABDUL KHADER GURUVAYOOR 3 SHRI. PARAKKAL ABDULLAH KUTTYAADI 4 SHRI. P.K.ABDU RUBB THIROORANGAADI 5 SHRI. V.ABDU REHIMAN THANUR 6 SHRI.ABID HUSSAIN THANGAL KOTTAKKAL 7 SHRI. V.S ACHUTHANANDHAN MALAMPUZHA 8 SHRI. T.A.AHAMMAD KABEER MANKADA 9 SMT. P AYISHA POTTI KOTTARAKKARA 10 SHRI. MANJALAMKUZHI ALI PERINTHALMANNA 11 SHRI. ANIL AKKARA WADAKANCHERRY 12 SHRI. A.P.ANIL KUMAR VANDOOR 13 SHRI. ANOOB JACOB PIRAVAM 14 SHRI. K.ANSALAN NEYYATTINKARA 15 SHRI. ANTONY JOHN KOTHAMANGALAM 16 SHRI. P.V.ANVAR NILAMBUR 17 SHRI. ANWAR SADATH ALUVA 18 PROF. K.U.ARUNAN IRINJALAKUDA 19 SHRI. C.K.ASHA VAIKOM 20 SHRI.K.BABU NENMARA 21 SHRI. I.C.BALAKRISHNAN SULTHANBATHERY Draft #42 of File 3110/1/2014/Elen Approved by JOINT REGISTRAR II (ADMIN) on 03-Feb-2020 10:50 AM - Page 1 22 SHRI. A.K.BALAN THARUR 23 SHRI. V.T.BALRAM THRITHALA 24 SHRI. P.K.BASHEER ERANAD 25 SMT. E.S.BIJIMOL PEERUMADE 26 SHRI. E.CHANDRASEKHARAN KANHANGED 27 SHRI. K.DASAN QUILANDY 28 SHRI. B.D DEVASSY CHALAKUDI 29 SHRI. C.DIVAKARAN NEDUMANGAD 30 SHRI. V.K.IBRAHIM KUNJU KALAMASSERY 31 SHRI. ELDO ABRAHAM MUVATTUPUZHA 32 SHRI. ELDOSE P KANNAPPILLIL PERUMBAVOOR 33 SHRI. K.B.GANESH KUMAR PATHANAPURAM 34 SMT. GEETHA GOPI NATTIKA 35 SHRI. GEORGE M THOMAS THIRUVAMBADI 36 SHRI. -

Impact of Coastal Erosion on Fisheries मत्स्यपालन, पशुपालनऔरडेयरीमंत्र

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF FISHERIES, ANIMAL HUSBANDRY AND DAIRYING DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION No. 313 TO BE ANSWERED ON 10TH AUGUST, 2021 Impact of Coastal Erosion on Fisheries *313: ADV. ADOOR PRAKASH: Will the Minister of FISHERIES, ANIMAL HUSBANDRY AND DAIRYING मत्स्यपालन, पशुपालनऔरडेयरीमंत्री be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government is aware of the struggle of fishermen families due to fast rising coastal erosion in the country; (b) whether the Government sought report from the States to review the impact of coastal erosion and if so, the details thereof; (c) the areas which are most affected with coastal erosion, State-wise; (d) whether the Government is aware that coastal areas in the State of Kerala are worst hit and majority of shoreline has been eroded and if so, the details thereof; and (e) whether the Government will consider special assistance to the State for effective preventive measures in this regard and if so, the details thereof? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF FISHERIES, ANIMAL HUSBANDRYAND DAIRYING (PARSHOTTAM RUPALA) (a) to (e): A Statement is placed on the Table of the House. ***** Statement referred to in reply to the Lok Sabha Starred Question No. *313 put in by Adv. Adoor Prakash, Member of Parliament for answer on 10th August, 2021 regarding Impact of Coastal Erosion on Fisheries (a) to (e): Some stretches of India’s shoreline are subject to varying degree of erosion due to natural causes or anthropogenic activities. The coastal erosion does impact coastal communities residing in the erosion prone areas including fishermen communities. -

Adoor Prakash [I.N.C

ADOOR PRAKASH [I.N.C. – KONNI] Son of late N. Kunjuraman and Smt. V. M. Vilasini; born at Adoor on 24th May 1955; B.A., LL.B.; Advocate, Political and Trade Union Worker. Entered politics through student movement; Was, President, K.S.U. (I) Kollam Taluk Committee (1976-77), K.S.U.(I) Kollam District Committee (1978-79); Vice President, K.S.U. (I) State Committee (1979-81); General Secretary, Youth Congress (I) Kollam District Committee (1981-84); President, Youth Congress(I) Pathanamthitta District (1984-88); General Secretary, Youth Congress(I) State Committee (1988-92). Joint Secretary, KPCC (I) (1997-2001); elected Member of the KPCC(I) from 1992; Vice President, D.C.C.(I), Pathanamthitta from 1993. Also held the posts of Working President, Kerala Private College Employees Association and General Secretary, Kerala State Electricity Employees Congress; President, Pampa Rubber Employees Association, Traco Cable Employees Association, Financial Enterprises Employees Congress; President, Adoor Taluk Taxi and Mini Vehicles Drivers Congress; Director, Kerala State Co-operative Bank, Kerala State Co- operative Rubber Marketing Federation, District Co-operative Bank, Pathanamthitta; President, Adoor Taluk Co-operative Rubber Marketing Society; President, Other Backward Class Co-operative Agriculture Society. 36 FOURTEENTH KERALA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Was Minister for Food and Civil Supplies and Consumer Affairs, Printing and Stationery from 5-9-2004 to 12-5-2006. In the Ministry headed by Shri Oommen Chandy, he was the Minister for Health and Coir,Pollution Control from 23-5-2011 to 11-4-2012 and the Minister for Revenue and Coir,Legal Meterology from 12-4-2012 to 20-5-2016. -

Subject Index, 1978

Economic and Political Weekly INDEX Vol. XIII, Nos. 1-52 January-December 1978 Ed = Editorials MMR = Money Market Review F = Feature RA= Review Article CL = Civil Liberties SA = Special Article C = Commentary D = Discussion P = Perspectives SS = Special Statistics BR = Book Review LE = Letters to Editor SUBJECT INDEX, 1978 ABORTION AFGHANISTAN Criteria for Denying Medical Termination End to 'Power of the Family': Afghanistan of Pregnancy: A Comment; Hunter P Mabry (Ed) (SA) Issue no: 18, May 06-12, p.742 Issue no: 36, Sep 09-15, p.1565 AFRICA ACCIDENTAL DEATHS African Summit (Ed) Anonymous Killer: Death (Ed) Issue no: 29, Jul 22-28, p.1157 Issue no: 20, May 20-26, p.828 Auxiliaries in Service of Imperialism: ADMINISTRATION Africa; Karrim Essack (C) Stirring the Administration; Romesh Thapar Issue no: 12, Mar 25-31, p.547 (F) Issue no: 14, Apr 08-14, p.597 From Bitter Division to Fragile Unity: OAU Summit (C) ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS Issue no: 35, Sep 02-08, p.1501 Administrative Improvement at Organisation Level: A System Design; A P Saxena Operation ORTAG: Africa; B Radhakrishna (RA) Rao (C) Issue no: 08, Feb 25-Mar 03, p.M16 Issue no: 03, Jan 21-27, p.96 Stirring the Administration; Romesh Thapar AGRARIAN REFORMS (F) Raking-Up Muck and Magic for Agricultural Issue no: 14, Apr 08-14, p.597 Progress; Ian Carruthers (C) Issue no: 20, May 20-26, p.834 ADULT EDUCATION Paper Plan (Ed) AGRARIAN RELATIONS Issue no: 27, Jul 08-14, p.1085 Agrarian Relations in Two Rice Regions of Kerala; Joan P Mencher (SA) ADVERTISING Issue no: 06-07, Feb 11-24, -

Shri.Ramesh Chennithala, Hon'ble Home Minister of Kerala

Shri.Ramesh Chennithala, Hon’ble Home Minister of Kerala inaugurated Neera Processing Plant of Karappuram Coconut Producer Company Ltd, Alappuzha, Kerala on 10-July-2015 Coconut Farmers Need to Focus More on Product Diversification: Ramesh Chennithala Coconut farmers should focus more or product diversification and quality of the Church, who has been supporting the activities of the company from the beginning. Dr. value-added products, opined Shri. Ramesh Chennithala, Home Minister, Govt. of P.K. Mani, CEO, Karappuram Coconut Producer’s Company, presented report. Adv. Kerala, while inaugurating the Neera plant set up by Karappuram Coconut Producer’s A.M. Arif MLA, Adv. U. Prathibhahari, President, Alappuzha District Panchayath, Mr. Company Limited at Ayyappanchery in Alappuzha on Friday. He also said that Suresh Richard, District Excise Deputy Commissioner, Shri. Shajahan Kanjiravilayil, finding a market for the products is one of the important things to be kept in mind. Chairman, Consortium of Coconut Producer Companies ets were present at the event. The Home Minister also said that the farmer producer companies have to concentrate Adv. D. PriyeshKumar, Chairman, Karappuram Coconut Producer’s Company Ltd more on bringing out quality products, which would help them get an easy entry into (KCPCL) delivered the welcome speech and Shri. T.S. Viswan, Director, KCPCL, international markets. The minister also praised the measures taken by Coconut delivered vote of thanks. The inaugural ceremony kick started with a musical event lead Development Board and the Department of Excise for making Neera project by famous singer Kumari Kanmani. successful in the state. Shri. Ramesh Chennithala also said that though the people in The Neera plant, located at Ayyappanchery in Alappuzha, has a capacity to produce Kerala are late in realizing the potential of coconut, they have started bringing out 2500 litres of Neera per day.