Impact of Resettlement on Scheduled Tribes in Kerala: a Study on Aralam Farm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Alienation and Livelihood Problems of Scheduled Tribes in Kerala

Research on Humanities and Social Sciences www.iiste.org ISSN (Paper)2224-5766 ISSN (Online)2225-0484 (Online) Vol.4, No.10, 2014 Land Alienation and Livelihood Problems of Scheduled Tribes in Kerala Dr. Haseena V.A Assistant professor, Post Graduate Department of Economics, M.E.S Asmabi College P.Vemballur, Kodunagllur, Thrissur, Kerala Email: [email protected] Introduction The word 'tribe' is generally used for a socially cohesive unit, associated with a territory, the member of which regards them as politically autonomous. Often a tribe possesses a distinct dialect and distinct cultural traits. Tribe can be defined as a “collection of families bearing a common name, speaking a common dialect, occupying or professing to occupy a common territory and is not usually endogamous though originally it might have been so”. According to R.N. Mukherjee, a tribe is that human group, whose members have common interest, territory, language, social law and economic occupation. Scheduled Tribes in India are generally considered to be ‘Adivasis,’ meaning indigenous people or original inhabitants of the country. The tribes have been confined to low status and are often physically and socially isolated instead of being absorbed in the mainstream Hindu population. Psychologically, the Scheduled Tribes often experience passive indifference that may take the form of exclusion from educational opportunities, social participation, and access to their own land. All tribal communities are not alike. They are products of different historical and social conditions. They belong to different racial stocks and religious backgrounds and speak different dialects. Discrimination against women, occupational differentiation, and emphasis on status and hierarchical social ordering that characterize the predominant mainstream culture are generally absent among the tribal groups. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kannur District from 19.04.2020To25.04.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kannur district from 19.04.2020to25.04.2020 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Name of the Age & Address of Cr. No & Police Sl. No. father of which Time of Officer, at which Accused Sex Accused Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 560/2020 U/s 269,271,188 IPC & Sec ZHATTIYAL 118(e) of KP Balakrishnan NOTICE HOUSE, Chirakkal 25-04- Act &4(2)(f) VALAPATTA 19, Si of Police SERVED - J 1 Risan k RASAQUE CHIRAkkal Amsom 2020 at r/w Sec 5 of NAM Male Valapattanam F C M - II, amsom,kollarathin Puthiyatheru 12:45 Hrs Kerala (KANNUR) P S KANNUR gal Epidermis Decease Audinance 2020 267/2020 U/s KRISNA KRIPA NOTICE NEW MAHE 25-04- 270,188 IPC & RATHEESH J RAJATH NALAKATH 23, HOUSE,Nr. New Mahe SERVED - J 2 AMSOM MAHE 2020 at 118(e) of KP .S, SI OF VEERAMANI, VEERAMANI Male HEALTH CENTER, (KANNUR) F C M, PALAM 19:45 Hrs Act & 5 r/w of POLICE, PUNNOL THALASSERY KEDO 163/2020 U/s U/S 188, 269 Ipc, 118(e) of Kunnath house, kp act & sec 5 NOTICE 25-04- Abdhul 28, aAyyappankavu, r/w 4 of ARALAM SERVED - J 3 Abdulla k Aralam town 2020 at Sudheer k Rashhed Male Muzhakunnu kerala (KANNUR) F C M, 19:25 Hrs Amsom epidemic MATTANNUR diseases ordinance 2020 149/2020 U/s 188,269 NOTICE Pathiriyad 25-04- 19, Raji Nivas,Pinarayi IPC,118(e) of Pinarayi Vinod Kumar.P SERVED - A 4 Sajid.K Basheer amsom, 2020 at Male amsom Pinarayi KP Act & 4(2) (KANNUR) C ,SI of Police C J M, Mambaram 18:40 Hrs (f) r/w 5 of THALASSERY KEDO 2020 317/2020 U/s 188, 269 IPC & 118(e) of KP Act & Sec. -

Patterns of Discovery of Birds in Kerala Breeding of Black-Winged

Vol.14 (1-3) Jan-Dec. 2016 newsletter of malabar natural history society Akkulam Lake: Changes in the birdlife Breeding of in two decades Black-winged Patterns of Stilt Discovery of at Munderi Birds in Kerala Kadavu European Bee-eater Odonates from Thrissur of Kadavoor village District, Kerala Common Pochard Fulvous Whistling Duck A new duck species - An addition to the in Kerala Bird list of - Kerala for subscription scan this qr code Contents Vol.14 (1-3)Jan-Dec. 2016 Executive Committee Patterns of Discovery of Birds in Kerala ................................................... 6 President Mr. Sathyan Meppayur From the Field .......................................................................................................... 13 Secretary Akkulam Lake: Changes in the birdlife in two decades ..................... 14 Dr. Muhamed Jafer Palot A Checklist of Odonates of Kadavoor village, Vice President Mr. S. Arjun Ernakulam district, Kerala................................................................................ 21 Jt. Secretary Breeding of Black-winged Stilt At Munderi Kadavu, Mr. K.G. Bimalnath Kattampally Wetlands, Kannur ...................................................................... 23 Treasurer Common Pochard/ Aythya ferina Dr. Muhamed Rafeek A.P. M. A new duck species in Kerala .......................................................................... 25 Members Eurasian Coot / Fulica atra Dr.T.N. Vijayakumar affected by progressive greying ..................................................................... 27 -

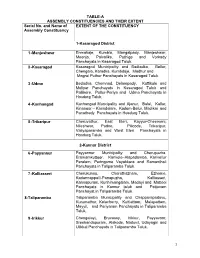

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

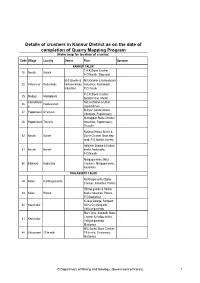

Details of Crushers in Kannur District As on the Date of Completion Of

Details of crushers in Kannur District as on the date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of crusher) Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator KANNUR TALUK T.A.K.Stone Crusher , 16 Narath Narath P.O.Narath, Step road M/S Granite & M/S Granite & Hollowbricks 20 Valiyannur Kadankode Holloaw bricks, Industries, Kadankode , industries P.O.Varam P.C.K.Stone Crusher, 25 Madayi Madaippara Balakrishnan, Madai Cherukkunn Natural Stone Crusher, 26 Pookavanam u Jayakrishnan Muliyan Constructions, 27 Pappinisseri Chunkam Chunkam, Pappinissery Muthappan Stone Crusher 28 Pappinisseri Thuruthi Industries, Pappinissery, Thuruthi National Hollow Bricks & 52 Narath Narath Stone Crusher, Near step road, P.O.Narath, Kannur Abhilash Granite & Hollow 53 Narath Narath bricks, Neduvathu, P.O.Narath Maligaparambu Metal 60 Edakkad Kadachira Crushers, Maligaparambu, Kadachira THALASSERY TALUK Karithurparambu Stone 38 Kolari Karithurparambu Crusher, Industries, Porora Hill top granite & Hollow 39 Kolari Porora bricks industries, Porora, P.O.Mattannur K.Jose George, Sampath 40 Keezhallur Stone Crushing unit, Velliyamparambu Mary Jose, Sampath Stone Crusher & Hollow bricks, 41 Keezhallur Velliyamparambu, Mattannur M/S Santhi Stone Crusher, 44 Chavesseri 19 th mile 19 th mile, Chavassery, Mattannur © Department of Mining and Geology, Government of Kerala. 1 Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator M/S Conical Hollow bricks 45 Chavesseri Parambil industries, Chavassery, Mattannur Jaya Metals, 46 Keezhur Uliyil Choothuvepumpara K.P.Sathar, Blue Diamond Vellayamparamb 47 Keezhallur Granite Industries, u Velliyamparambu M/S Classic Stone Crusher 48 Keezhallur Vellay & Hollow Bricks Industries, Vellayamparambu C.Laxmanan, Uthara Stone 49 Koodali Vellaparambu Crusher, Vellaparambu Fivestar Stone Crusher & Hollow Bricks, 50 Keezhur Keezhurkunnu Keezhurkunnu, Keezhur P.O. -

Date of Publication of Tender / Bids

GOVERNMENT OF KERALA LOCAL SELF GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENT Office of the Assistant Executive Engineer,LSGD Sub Division, Iritty Block Panchayath e-Tender No: D/TNR/3/2016-17 Dated 17/11/2016 e-Government Procurement (e-GP) NOTICE INVITING TENDER The Assistant Executive Engineer, LSGD Sub Division, Iritty Block Panchayath, LSG (EW) Department for and on behalf of the Governor of Kerala invites online bids from the registered bidders of PWD. Date of publication of Tender / Bids - 19/11/2016 11:00 AM Last date and time of Receipt of Tender / Bids - 26/11/2016 11:00 AM Date and Time of Opening of Tender - 29/11/2016 11:00 AM Sl. Name of Work PAC Estimate EMD Fee VAT Total Fee Period of Classification No. Amount including completion of Bidder VAT (in months) 1 Iritty Block Panchayath Project No. S0018/17 - Tarring Works to 4,95,448 5,00,000 12,500 1,000 50 1,050 4 D Class and Ottakombanchal Kunnu Road in Pyam GP above 2 Iritty Block Panchayath Project No. S0019/17 - Tarring Works to 4,94,038 5,00,000 12,500 1,000 50 1,050 4 D Class and Thazhekappil Karakkattu Junction Kochangadi Road km 0/065 to above 0/155 in Ayyankunnu GP 3 Iritty Block Panchayath Project No. S0020/17 - Tarring Works to 8,99,546 9,00,000 22,500 1,800 90 1,890 4 D Class and Uruppumkutti Ezhamkadavu Road km 0/260 to 0/360 in above Ayyankunnu GP 4 Iritty Block Panchayath Project No. S0021/17 - Tarring works to 7,96,213 8,00,000 20,000 1,600 80 1,680 4 D Class and Chedikkulam Pannimoola Road in Aralam GP above 5 Iritty Block Panchayath Project No. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kannur District from 09.12.2018To15.12.2018

Accused Persons arrested in Kannur district from 09.12.2018to15.12.2018 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kidinhiyil House, Cr No 682/18 Nelson 38/18 Chembilode 09.12.2018 Bailed by 1 Pramod.K Balan Nair Chirakkuthazhe, U/S 118 (a) of Edakkad Nicholause, SI ,Male amsom Chala at 18.05 hrs Police Thottada KP Act of Police Edakkad Cr No 683/18 Mahesh 19/18,M Nallamthottathil amsom Nr 09.12.2018 Bailed by 2 Vishnu.P Prasannan U/S 118 (a) of Edakkad Kandambeth ale House, Edakkad PO Mathrubhumi at 23.50 hrs Police KP Act ,SI Of Police Office Prakasan,SI of Thazheppurakkal(H),C 636/18U/s Ahammadkutt 60/18,m 2018-12- Sreekandapur Police,Sreekan Released on 3 Youseph hengalayi Amsom Kottoor 279IPC&185 of y ale 09T20:10 am dpauram bail; Cheramoola MV Act Police Station VijilNivas, 708/18 u/s 118( 29, Chakkarakkal 09 12 2018 Released on 4 Sherin Prakash Prakashan Uchulikunnummal, e) of KP Act & Chakkarakkal Babumon SI Male Town at 0030 hrs bail Mamba 185 of MV Act 09 12 2018 709/18 u/s 118( 57, Koyodan House, Released on 5 Pavithran K Sankaran Kanhirode at e) of KP Act & Chakkarakkal Babumon SI Male Koodali Mandapam bail 1100 hrs 185 of MV Act 710/18 u/s 118( 23, Thattantevalappil(H), 09 12 2018 e) of KP Act & Released on 6 Shijil KC Rajan Sona Road Chakkarakkal Babumon SI Male Kannadivelicham at 1730 -

The State of Art of Tribal Studies an Annotated Bibliography

The State of Art of Tribal Studies An Annotated Bibliography Dr. Nupur Tiwary Associate Professor in Political Science and Rural Development Head, Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Tribal Affairs Contact Us: Centre of Tribal Research and Exploration, Indian Institute of Public Administration, Indraprastha Estate, Ring Road, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi, Delhi 110002 CENTRE OF TRIBAL RESEARCH & EXPLORATION (COTREX) Phone: 011-23468340, (011)8375,8356 (A Centre of Excellence under the aegis of Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India) Fax: 011-23702440 INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Email: [email protected] NUP 9811426024 The State of Art of Tribal Studies An Annotated Bibliography Edited by: Dr. Nupur Tiwary Associate Professor in Political Science and Rural Development Head, Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Tribal Affairs CENTRE OF TRIBAL RESEARCH & EXPLORATION (COTREX) (A Centre of Excellence under Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India) INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION THE STATE OF ART OF TRIBAL STUDIES | 1 Acknowledgment This volume is based on the report of the study entrusted to the Centre of Tribal Research and Exploration (COTREX) established at the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA), a Centre of Excellence (CoE) under the aegis of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA), Government of India by the Ministry. The seed for the study was implanted in the 2018-19 action plan of the CoE when the Ministry of Tribal Affairs advised the CoE team to carried out the documentation of available literatures on tribal affairs and analyze the state of art. As the Head of CoE, I‘d like, first of all, to thank Shri. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Revised Draft Prepared by Premlal .M, DHRD on 11 on .M, DHRD Premlal by Prepared Draft Revised th July 2011 2011 July IPP519 1 TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR JALANIDHI -2 Introduction The problem of tribal development has reached a critical stage and has assumed an added significance in the context of high priority accorded to social justice in a new planning effort. The Indian constitution enjoin on the state the responsibility to promote, with special care, the education and economic interests of scheduled tribes and protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation. Their development is a special responsibility of the state. The successive plans have been laying considerable emphasis on special development programmes for the tribals. The physical development of an area itself will not be sufficient. It must go hand in hand with the development of the people of the region. No section of any community should be allowed to expose to the exploitation and benefits of the development must diffuse as widely as possible. Background Jalanidhi phase 1 covered 8664 tribal households in 33 Grama panchayaths, during the first phase of Jalanidhi KRWSA adopted separate Tribal development plan in 10 Grama panchayaths namely Agali, Pudur, Sholayur, Muthalamada, Pothukal, Athirappally, Perumatty , Kulathupuzha and Thirunelly and Chaliyar. It is evident that the coverage of tribal population is much higher than in TDP comparing to general water supply and sanitation project. The tribal, who hitherto had received free service, have accepted the change in thinking and contributed Rs.83.6 lakhs in cash and labor to the beneficiary share. -

Challenges Before Kerala's Landless: the Story of Aralam Farm

SPECIAL ARTICLE Challenges before Kerala’s Landless: The Story of Aralam Farm M S Sreerekha Whether from a class perspective or from a community truggles waged by the landless at Muthanga, Chengara identity perspective, it is undeniably the biggest failure and elsewhere for more than a decade indicate how that decades after the land reforms, a good majority of SK erala’s much-fl aunted history of land reforms is becom- ing increasingly questionable. For the adivasi community, the the dalits and adivasis in Kerala remain fully landless. In struggle has been essentially about the restoration of their alien- the context of the Supreme Court verdict of 21 July 2009, ated land. Every piece of law enacted towards this has failed or which rejected a stay order by the Kerala High Court on made to fail; the passing of the Kerala Restriction on Transfer by important sections of the Kerala Restriction on Transfer and Restoration of Lands to Scheduled Tribes Act, 1999 by the state assembly was yet another blow. The Supreme Court verdict by and Restoration of Lands to Scheduled Tribes Act, on 21 July 2009 rejected a stay order by the Kerala High Court on 1999 and the new scenario where the legislature and the important sections of this act. This verdict has validated the 1999 judiciary proclaim that the adivasi community has now Act. For the adivasi population of around 3.21 lakh (of which 80% agreed for alternate land, and therefore, the issue of are landless), as far as restoration of their alienated land is con- cerned, this judgment is a battle lost legally. -

Report of Rapid Impact Assessment of Flood/ Landslides on Biodiversity Focus on Community Perspectives of the Affect on Biodiversity and Ecosystems

IMPACT OF FLOOD/ LANDSLIDES ON BIODIVERSITY COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVES AUGUST 2018 KERALA state BIODIVERSITY board 1 IMPACT OF FLOOD/LANDSLIDES ON BIODIVERSITY - COMMUnity Perspectives August 2018 Editor in Chief Dr S.C. Joshi IFS (Retd) Chairman, Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram Editorial team Dr. V. Balakrishnan Member Secretary, Kerala State Biodiversity Board Dr. Preetha N. Mrs. Mithrambika N. B. Dr. Baiju Lal B. Dr .Pradeep S. Dr . Suresh T. Mrs. Sunitha Menon Typography : Mrs. Ajmi U.R. Design: Shinelal Published by Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram 2 FOREWORD Kerala is the only state in India where Biodiversity Management Committees (BMC) has been constituted in all Panchayats, Municipalities and Corporation way back in 2012. The BMCs of Kerala has also been declared as Environmental watch groups by the Government of Kerala vide GO No 04/13/Envt dated 13.05.2013. In Kerala after the devastating natural disasters of August 2018 Post Disaster Needs Assessment ( PDNA) has been conducted officially by international organizations. The present report of Rapid Impact Assessment of flood/ landslides on Biodiversity focus on community perspectives of the affect on Biodiversity and Ecosystems. It is for the first time in India that such an assessment of impact of natural disasters on Biodiversity was conducted at LSG level and it is a collaborative effort of BMC and Kerala State Biodiversity Board (KSBB). More importantly each of the 187 BMCs who were involved had also outlined the major causes for such an impact as perceived by them and suggested strategies for biodiversity conservation at local level. Being a study conducted by local community all efforts has been made to incorporate practical approaches for prioritizing areas for biodiversity conservation which can be implemented at local level. -

Land Question and the Tribals of Kerala

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 2, ISSUE 9, SEPTEMBER 2013 ISSN 2277-8616 Land Question And The Tribals Of Kerala Nithya N.R. Abstract: The paper seeks to examine the land question of tribals in Kerala, India. In the context of developing countries such as India, the state of Kerala has often been cited as a model. Notable among its achievements is the good health indicator in terms of mortality and fertility rates and high levels of utilization of formal health services and cent percent literacy. Later, it was observed that this model has several outlier communities in which tribal communities were the most victimized ones. The tribals are children of nature and their lifestyle is conditioned by the Ecosystem. After the sixty years of formation of the state tribals continues as one of the most marginalized community within the state, the post globalised developmental projects and developmental dreams of the state has again made the deprivation of the tribals of Kerala and the developmental divide has increased between the tribal and non-tribal in the state. The paper argues that deprivation of land and forests are the worst forms of oppression that these people experience. Index Terms: Land, Tribals, India, Kerala, Globalization, Government, Alienation ———————————————————— 1 INTRODUCTION There are over 700 Scheduled Tribes notified under Article The forest occupies a central position in tribal culture and 342 of the Constitution of India, spread over different States economy. India is also characterized by having second and Union Territories of the country. Tribals are among the largest tribal (Adivasis) population in the world.