India and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha District Gazetteers Nabarangpur

ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR DR. TARADATT, IAS CHIEF EDITOR, GAZETTEERS & DIRECTOR GENERAL, TRAINING COORDINATION GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ii iii PREFACE The Gazetteer is an authoritative document that describes a District in all its hues–the economy, society, political and administrative setup, its history, geography, climate and natural phenomena, biodiversity and natural resource endowments. It highlights key developments over time in all such facets, whilst serving as a placeholder for the timelessness of its unique culture and ethos. It permits viewing a District beyond the prismatic image of a geographical or administrative unit, since the Gazetteer holistically captures its socio-cultural diversity, traditions, and practices, the creative contributions and industriousness of its people and luminaries, and builds on the economic, commercial and social interplay with the rest of the State and the country at large. The document which is a centrepiece of the District, is developed and brought out by the State administration with the cooperation and contributions of all concerned. Its purpose is to generate awareness, public consciousness, spirit of cooperation, pride in contribution to the development of a District, and to serve multifarious interests and address concerns of the people of a District and others in any way concerned. Historically, the ―Imperial Gazetteers‖ were prepared by Colonial administrators for the six Districts of the then Orissa, namely, Angul, Balasore, Cuttack, Koraput, Puri, and Sambalpur. After Independence, the Scheme for compilation of District Gazetteers devolved from the Central Sector to the State Sector in 1957. -

Status of Entitlement Issued by Accountant General in July, 2020 in Respect of Gazetted Officers

ENTITLEMENTS AUTHORISED/ISSUED BY ACCOUNTANT GENERAL IN July 2020 IN RESPECT OF GAZETTED OFFICER PAY SLIP ISSUED NAME DESIGNATION STATUS Ajay Kumar अधधकण अभभययतत (ससवतभनववत) ISSUED Ajay Kumar Srivastava No-1 PRINCIPAL JUDGE, FAMILY COURT ISSUED Akhilesh Kumar District co-operative officer ISSUED Alok Kumar TECHNICAL ADVISOR ISSUED Amar Singh कतयरपतलक अभभययतत, ISSUED Amarendra Prasad Singh (भनलयभबत ) ISSUED Amrit Lal Meena अपर ममखय सभचव, ISSUED Anil Kumar Superintending Engineer, ISSUED Anil Kumar Anand Senior Reporter, ISSUED Anil Kumar Thakur Retired Medical Officer, ISSUED Anwar Hussain Member, Bihar Police Sub-ordinate Services Commission, Santosh Mansion, ISSUED B-Block, Near R.P.S. Law College, Arbind Prasad Shahi Retd District Immunisation Officer, Katihar ISSUED Arun Kumar Medical Officer, ISSUED Arun Kumar Sinha Executive Engineer, ISSUED Arun Kumar Srivastava PRINCIPAL JUDGE, FAMILY COURT ISSUED Arunish Chawla Central deputation ISSUED Arvind Kumar Pandey Principal Chief Conservator of Forests(HOFF) ISSUED Ashesh Kumar Retd. Superintendent ISSUED Ashok Kumar Chaudhary Superintending Engineer, ISSUED Ashok Kumar Jha Executive Engineer(NABARD,External Sustained), Chief Engineer(Budget & ISSUED Planning) Ashok Kumar Yadav Dy. Director, Medical Education Deptt. ISSUED Atma Nand Kumar Civil Surgeon Cum Chief Medical Officer ISSUED Awdhesh Kumar Civil Surgeon Cum Chief Medical Officer ISSUED Ayodhya Singh Additional S.P. (Operation), ISSUED Bharat Singh Professor ISSUED Bhaskar Chandra Bharti DIVISIONAL FOREST OFFICER, PURNEA ISSUED -

APPENDIX-V FOREIGN CONTRIBUTION (REGULATION) ACT, 1976 During the Emergency Regime in the Mid-1970S, Voluntary Organizations

APPENDIX-V FOREIGN CONTRIBUTION (REGULATION) ACT, 1976 During the Emergency Regime in the mid-1970s, voluntary organizations played a significant role in Jayaprakash Narayan's (JP) movement against Mrs. Indira Gandhi. With the intervention of voluntary organizations, JP movement received funds from external sources. The government became suspicious of the N GOs as mentioned in the previous chapter and thus appointed a few prominent people in establishing the Kudal Commission to investigate the ways in which JP movement functioned. Interestingly, the findings of the investigating team prompted the passage of the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act during the Emergency Period. The government prepared a Bill and put it up for approval in 1973 to regulate or control the use of foreign aid which arrived in India in the form of donations or charity but it did not pass as an Act in the same year due to certain reasons undisclosed. However, in 1976, Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act was introduced to basically monitor the inflow of funds from foreign countries by philanthropists, individuals, groups, society or organization. Basically, this Act was enacted with a view to ensure that Parliamentary, political or academic institutions, voluntary organizations and individuals who are working in significant areas of national life may function in a direction consistent with the values of a sovereign democratic republic. Any organizations that seek foreign funds have to register with the Ministry of Home Affairs, FCRA, and New Delhi. This Act is applicable to every state in India including organizations, societies, companies or corporations in the country. NGOs can apply through the FC-8 Form for a permanent number. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : MUMBAI Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 16.01.001 SAKHARAM SHETH VIDYALAYA, KALYAN,THANE 185 185 22 57 52 29 160 86.48 27210508002 16.01.002 VIDYANIKETAN,PAL PYUJO MANPADA, DOMBIVLI-E, THANE 226 226 198 28 0 0 226 100.00 27210507603 16.01.003 ST.TERESA CONVENT 175 175 132 41 2 0 175 100.00 27210507403 H.SCHOOL,KOLEGAON,DOMBIVLI,THANE 16.01.004 VIVIDLAXI VIDYA, GOLAVALI, 46 46 2 7 13 11 33 71.73 27210508504 DOMBIVLI-E,KALYAN,THANE 16.01.005 SHANKESHWAR MADHYAMIK VID.DOMBIVALI,KALYAN, THANE 33 33 11 11 11 0 33 100.00 27210507115 16.01.006 RAYATE VIBHAG HIGH SCHOOL, RAYATE, KALYAN, THANE 151 151 37 60 36 10 143 94.70 27210501802 16.01.007 SHRI SAI KRUPA LATE.M.S.PISAL VID.JAMBHUL,KULGAON 30 30 12 9 2 6 29 96.66 27210504702 16.01.008 MARALESHWAR VIDYALAYA, MHARAL, KALYAN, DIST.THANE 152 152 56 48 39 4 147 96.71 27210506307 16.01.009 JAGRUTI VIDYALAYA, DAHAGOAN VAVHOLI,KALYAN,THANE 68 68 20 26 20 1 67 98.52 27210500502 16.01.010 MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KUNDE MAMNOLI, KALYAN, THANE 53 53 14 29 9 1 53 100.00 27210505802 16.01.011 SMT.G.L.BELKADE MADHYA.VIDYALAYA,KHADAVALI,THANE 37 36 2 9 13 5 29 80.55 27210503705 16.01.012 GANGA GORJESHWER VIDYA MANDIR, FALEGAON, KALYAN 45 45 12 14 16 3 45 100.00 27210503403 16.01.013 KAKADPADA VIBHAG VIDYALAYA, VEHALE, KALYAN, THANE 50 50 17 13 -

Waromung an Ao Naga Village, Monograph Series, Part VI, Vol-I

@ MONOGRAPH CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 No. I VOLUME-I MONOGRAPH SERIES Part VI In vestigation Alemchiba Ao and Draft Research design, B. K. Roy Burman Supervision and Editing Foreword Asok Mitra Registrar General, InOla OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA WAROMUNG MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (an Ao Naga Village) NEW DELHI-ll Photographs -N. Alemchiba Ao K. C. Sharma Technical advice in describing the illustrations -Ruth Reeves Technical advice in mapping -Po Lal Maps and drawings including cover page -T. Keshava Rao S. Krishna pillai . Typing -B. N. Kapoor Tabulation -C. G. Jadhav Ganesh Dass S. C. Saxena S. P. Thukral Sudesh Chander K. K. Chawla J. K. Mongia Index & Final Checking -Ram Gopal Assistance to editor in arranging materials -T. Kapoor (Helped by Ram Gopal) Proof Reading - R. L. Gupta (Final Scrutiny) P. K. Sharma Didar Singh Dharam Pal D. C. Verma CONTENTS Pages Acknow ledgement IX Foreword XI Preface XIII-XIV Prelude XV-XVII I Introduction ... 1-11 II The People .. 12-43 III Economic Life ... .. e • 44-82 IV Social and Cultural Life •• 83-101 V Conclusion •• 102-103 Appendices .. 105-201 Index .... ... 203-210 Bibliography 211 LIST OF MAPS After Page Notional map of Mokokchung district showing location of the village under survey and other places that occur in the Report XVI 2 Notional map of Waromung showing Land-use-1963 2 3 Notional map of Waromung showing nature of slope 2 4 (a) Notional map of Waromung showing area under vegetation 2 4 (b) Notional map of Waromung showing distribution of vegetation type 2 5 (a) Outline of the residential area SO years ago 4 5 (b) Important public places and the residential pattern of Waromung 6 6 A field (Jhurn) Showing the distribution of crops 58 liST OF PLATES After Page I The war drum 4 2 The main road inside the village 6 3 The village Church 8 4 The Lower Primary School building . -

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples' Issues

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues Republic of India Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues REPUBLIC OF INDIA Submitted by: C.R Bijoy and Tiplut Nongbri Last updated: January 2013 Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations ‗developed‘ and ‗developing‘ countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. All rights reserved Table of Contents Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples‘ Issues – Republic of India ......................... 1 1.1 Definition .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Scheduled Tribes ......................................................................................... 4 2. Status of scheduled tribes ...................................................................................... 9 2.1 Occupation ........................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Poverty .......................................................................................................... -

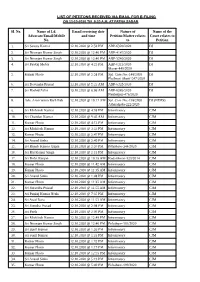

LIST of PETITONS RECEIVED VIA EMAIL for E-FILING Sl. No. Name

LIST OF PETITONS RECEIVED VIA EMAIL FOR E-FILING ON 13-10-2020 Till 9:30 A.M. AT PATNA SADAR Sl. No. Name of Ld. Email receiving date Nature of Name of the Advocate/Email/Mobile and time Petition/Matter relates Court relates to No. to Petition 1. Sri Sanjay Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 2:50 PM ABP-6320/2020 DJ 2. Sri Niranjan Kumar Singh 12.10.2020 @ 12:46 PM ABP-4187/2020 DJ 3. Sri Niranjan Kumar Singh 12.10.2020 @ 12:46 PM ABP-5240/2020 DJ 4. Sri Pankaj Mehta 12.10.2020 @ 4:23 PM ABP-6313/2020 DJ Maner-440/2020 5. Kumar Photo 12.10.2020 @ 5:58 PM Spl. Case No.-148/2020 DJ Phulwari Sharif-547/2020 6. Sri Devendra Prasad 13.10.2020 @ 5:22 AM ABP-6235/2020 DJ 7. Sri Rashid Zafar 13.10.2020 @ 6:06 AM ABP-6385/2020 DJ Naubatpur-476/2020 8. Adv. Association Barh Bab 12.10.2020 @ 10:17 AM Spl. Case No.-138/2020 DJ (NDPS) Athmalgola-222/2020 9. Sri Mithilesh Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 4:38 PM Informatory CJM 10. Sri Chandan Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 9:45 AM Informatory CJM 11. Kumar Photo 12.10.2020 @ 4:13 PM Informatory CJM 12. Sri Mithilesh Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 3:32 PM Informatory CJM 13. Kumar Photo 12.10.2020 @ 2:47 PM Informatory CJM 14. Sri Anand Sinha 12.10.2020 @ 2:40 PM Informatory CJM 15. Sri Rajesh Kumar Gupta 12.10.2020 @ 2:36 PM Pribahore-344/2020 CJM 16. -

Scheduled Tribes

Annual Report 2008-09 Ministry of Tribal Affairs Photographs Courtesy: Front Cover - Old Bonda by Shri Guntaka Gopala Reddy Back Cover - Dha Tribal in Wheat Land by Shri Vanam Paparao CONTENTS Chapters 1 Highlights of 2008-09 1-4 2 Activities of Ministry of Tribal Affairs- An Overview 5-7 3 The Ministry: An Introduction 8-16 4 National Commission for Scheduled Tribes 17-19 5 Tribal Development Strategy and Programmes 20-23 6 The Scheduled Tribes and the Scheduled Area 24-86 7 Programmes under Special Central Assistance to Tribal Sub-Plan 87-98 (SCA to TSP) and Article 275(1) of the Constitution 8 Programmes for Promotion of Education 99-114 9 Programmes for Support to Tribal Cooperative Marketing 115-124 Development Federation of India Ltd. and State level Corporations 10 Programmes for Promotion of Voluntary Action 125-164 11 Programmes for Development of Particularly Vulnerable 165-175 Tribal Groups (PTGs) 12 Research, Information and Mass Media 176-187 13 Focus on the North Eastern States 188-191 14 Right to Information Act, 2005 192-195 15 Draft National Tribal Policy 196-197 16 Displacement, Resettlement and Rehabilitation of Scheduled Tribes 198 17 Gender Issues 199-205 Annexures 3-A Organisation Chart - Ministry of Tribal Affairs 13 3-B Statement showing details of BE, RE & Expenditure 14-16 (Plan) for the years 2006-07, 2007-08 & 2008-09 5-A State-wise / UT- wise details of Annual Plan (AP) outlays for 2008-09 23 & status of the TSP formulated by States for Annual Plan (AP) 2008-09. 6-A Demographic Statistics : 2001 Census 38-39 -

District Census Handbook, Thane

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK THANE Compiled by THE MAHARASHTRA CENSUS DIRECTORATE BOMBAY PRINTED IN INDIA BY THE MANAGER, GOVERNMENT CENTRAL PRESS, BOMBAY AND PUBLISHED BY THE DIRECTOR, GOVERNMENT PRINTING, STATIONERY AND PUBLICATIONS, MAHARASHTRA STATE, BOMBAY 400 004 1986 [Price-Rs.30·00] MAHARASHTRA DISTRICT THANE o ADRA ANO NAGAR HAVELI o s y ARABIAN SEA II A G , Boundary, Stote I U.T. ...... ,. , Dtstnct _,_ o 5 TClhsa H'odqllarters: DCtrict, Tahsil National Highway ... NH 4 Stat. Highway 5H' Important M.talled Road .. Railway tine with statIOn, Broad Gauge River and Stream •.. Water features Village having 5000 and above population with name IIOTE M - PAFU OF' MDKHADA TAHSIL g~~~ Err. illJ~~r~a;~ Size', •••••• c- CHOLE Post and Telegro&m othce. PTO G.P-OAJAUANDHAN- PATHARLI [leg .... College O-OOMBIVLI Rest House RH MSH-M4JOR srAJE: HIJHWAIY Mud. Rock ." ~;] DiStRICT HEADQUARTERS IS ALSO .. TfIE TAHSIL HEADQUARTERS. Bo.ed upon SUI"'Ye)' 0' India map with the Per .....ion 0( the Surv.y.,.. G.,.roI of ancIo © Gover..... ,,, of Incfa Copyrtgh\ $8S. The territorial wat.,. rilndia extend irato the'.,a to a distance 01 tw.1w noutieol .... III80sured from the appropf'iG1. ba .. tin .. MOTIF Temples, mosques, churches, gurudwaras are not only the places of worship but are the faith centres to obtain peace of the mind. This beautiful temple of eleventh century is dedicated to Lord Shiva and is located at Ambernath town, 28 km away from district headquarter town of Thane and 60 km from Bombay by rail. The temple is in the many-cornered Chalukyan or Hemadpanti style, with cut-corner-domes and close fitting mortarless stones, carved throughout with half life-size human figures and with bands of tracery and belts of miniature elephants and musicians. -

Bihar Police Constable

Bihar Police Constable Online Form 2020 Central Selection Board of Constable CSBC Bihar Police Constable Recruitment 2020 Total 8415 Post Important Dates: Bihar Police Constable Form Start Date 13 November 2020 Bihar Consta ble 2020 Last Date 14 December 2020 CSBC Bihar Police Constable Last Date Payment 14 December 2020 Application Fees: • General / OBC / Other State : Rs. 450/- • SC / ST: Rs. 112/- Age Limit: • Age Calculate on 01 August 2020 • Minimum 18 Years & Maximum 25 Years Eligibility: • Intermediate in Any Stream from Any Recognized Board Vacancy Details: General EWS OBC EOBC OBC-Female SC ST Total 3489 842 980 1470 245 1307 82 8415 District Wise Vacancy Details: District Name Total Post District Name Total Post Patna 600 Madhubandi 40 Bhojpur 260 Saharsa 40 Kaimur 80 Madhepura 70 Aurangabad 100 Kishanganj 20 Jahanabad 80 Arriya 20 Muzaffarpur 400 Baka 250 Shivhar 20 Khagadiya 130 Betiyan 80 Begusarai 130 Saran 160 Lakhisarai 150 Gopalganj 100 Rail Patna 100 Bihar Military Police 01 Patna 248 Rail Katihar 100 B.R.O.S.B Patna 1206 Military Police Central Region 07 Central Area Patna 06 Horseman Military Police Ara 52 Tirhut Area, Muzaffapur 07 S.O.I.R.B. Bodhgaya 208 Punia Area 05 Magadh Area Gaya 05 Koshi Area Saharsha 15 Mithila Area Darbanga 09 Eastern Area Bhagalpur 14 Shahabad Area Dehari 02 Munger Area 08 Champaran Area Betiyan 12 Traffic Police H.Q. Patna 16 Begularsarai Area 06 Training H.Q. Patna 44 Bihar Police H.Q. Patna 90 Caste Department, Patna 40 Finance H.Q. Patna 20 State Other Backward Prosecution 44 Special Branch, Patna 468 Bureau Nalanda 240 Economic Offenses U nit , Patna 216 Rohtas 90 Supaul 70 Gaya 200 Purnia 230 Newada 250 Katihar 90 Arwal 06 Bhagalpur 90 Vaishali 150 Navgachiya 70 Sitamarhi 190 Munger 200 Motihari 80 Sekhpura 20 Siwan 100 Jamui 300 Darbangha 170 Rail Muzaffarpur 40 Samastipur 140 Military Police H.Q. -

Annual-Report-2018-2019-Compressed-Final.Pdf

S.N. Particulars Page No. I Highlights of Year 2018 – 2019 3 II Activities of Centers i. Rural Homoeopathic Hospital, Palghar 4-13 ii. Smt. Janaki Bachhu Dube Homoeopathic 14-31 Hospital, Bhopoli iii. Dahisar Branch Activities 32 iv. Dr. M.L. Dhawale Memorial Homoeopathic Medico 33- 39 Surgical and Research Centre, Malad v. Pune Branch Activities 40-41 III Urban Charitable Clinics 42-49 IV EMR Project 50-52 V Postgraduate Academic Activities 53-57 VII Our Supporters 58 Dr. M L Dhawale Memorial Trust 2 Annual Report 2018-19 Highlights of the Year 2018-19 MLDT’s Rural Homeopathic Hospital, Palghar received IMC Ramkrishna Bajaj National Quality Certificate 2018 Pre-accreditation entry level certification was received from NABH for allopathic services ICICI Bank has extended support to indigent Dialysis patients, Medical Mobile Van and Malnourishment project as their Corporate Social Responsibility Oracle has been a consistent partner in our fight against malnutrition in Vikramgadh Taluka for fourth year A team of Volunteers from Transworld celebrated international Women’s day at Bhopoli with more than 200 women. The Team performed a street-play to create awareness of menstrual hygiene. The day ended with watching PADAMAN to further remove taboo connected with the subject TATA Pro –engagers have voluntarily assisted the Malad, Palghar and Bhopoli hospital teams to provide professional help. They are working on a variety of projects ranging from data analysis to app development to creative writing Dr. M L Dhawale Memorial Trust 3 Annual Report 2018-19 DR. M.L. DHAWALE MEMORIAL TRUST’S RURAL HOMOEOPATHIC HOSPITAL, PALGHAR Main Highlights: Inauguration of the following facilities at the Rural Homoeopathic Hospital, Palghar Date: 30th September 2018 Prof.Ram Kapse Geriatric Care Center Dialysis Machine donated by Shri Harakchandbhai K Savla.