WARLMANPA LANGUAGE & COUNTRY David Nash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kimberley Itinerary (Travelwise Can Organise Your Flight from Any State

Kimberley Itinerary (Travelwise can organise your flight from any state to join this tour) Day 1 – Saturday 04th June 06.30am – Depart Boomerang Beach 06.50am – Depart Forster Keys 07.00am – Depart Golden Ponds 07.05am – Depart Southern Parkway & Akala 07.15am – Depart Pacific Smiles 07.25am – Depart Club Forster 07.35am – Depart Tuncurry Beach St Bus Shelter 07.40am – Depart Chapmans Rd Tuncurry 08.10am – Depart Taree South Service Centre 08.30am – Depart Club Taree 08.45am – Depart Caravilla Motel Taree 09.00am – Depart Taree Airport 09.50am – Arrive Port Doughnut (comfort stop) 10.00am – Depart Port Doughnut 01.10pm – Arrive Walcha (lunch at own leisure) 02.00pm – Depart Walcha 05.30pm – Arrive Burk & Wills Motor Inn, Moree NSW 07.00pm – Dinner Day 2 – Sunday 05th June 07.00am – Breakfast 08.30am – Depart Moree 11.15am – Arrive Saint George QLD (lunch at own leisure) 12.10pm – Depart Saint George 05.45pm – Arrive Tambo Mill Motel, Tambo QLD Enjoy the slower pace and all the history that the oldest town in Outback Queensland has to offer (including town chicken races). 07.00pm – Dinner Provided (Carrangarra Hotel) Day 3 – Monday 06th June 07.00am – Breakfast Provided (Fanny Mae’s) 08.00pm – Depart Tambo 10.00am – Arrive Lara Station wetlands (morning tea provided) 10.30am – Depart Lara Station 12.00pm – Arrive Qantas Founders Museum Longreach (tour & lunch provided) Qantas Founders Museum is an award winning, world-class museum and cultural display, eloquently telling the story of Qantas through interpretive displays, interactive exhibits, original and replica aircraft and an impressive collection of genuine artifacts. -

Than One Way to Catch a Frog: a Study of Children's

More than one way to catch a frog: A study of children’s discourse in an Australian contact language Samantha Disbray Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics University of Melbourne December, 2008 Declaration This is to certify that: a. this thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD b. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all material used c. the text is less than 100,000 words, exclusive of tables, figures, maps, examples, appendices and bibliography ____________________________ Samantha Disbray Abstract Children everywhere learn to tell stories. One important aspect of story telling is the way characters are introduced and then moved through the story. Telling a story to a naïve listener places varied demands on a speaker. As the story plot develops, the speaker must set and re-set these parameters for referring to characters, as well as the temporal and spatial parameters of the story. To these cognitive and linguistic tasks is the added social and pragmatic task of monitoring the knowledge and attention states of their listener. The speaker must ensure that the listener can identify the characters, and so must anticipate their listener’s knowledge and on-going mental image of the story. How speakers do this depends on cultural conventions and on the resources of the language(s) they speak. For the child speaker the development narrative competence involves an integration, on-line, of a number of skills, some of which are not fully established until the later childhood years. -

Endangered Songs and Endangered Languages

Endangered Songs and Endangered Languages Allan Marett and Linda Barwick Music department, University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia [[email protected], [email protected]] Abstract Without immediate action many Indigenous music and dance traditions are in danger of extinction with It is widely reported in Australia and elsewhere that songs are potentially destructive consequences for the fabric of considered by culture bearers to be the “crown jewels” of Indigenous society and culture. endangered cultural heritages whose knowledge systems have hitherto been maintained without the aid of writing. It is precisely these specialised repertoires of our intangible The recording and documenting of the remaining cultural heritage that are most endangered, even in a traditions is a matter of the highest priority both for comparatively healthy language. Only the older members of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Many of the community tend to have full command of the poetics of our foremost composers and singers have already song, even in cases where the language continues to be spoken passed away leaving little or no record. (Garma by younger people. Taking a number of case studies from Statement on Indigenous Music and Performance Australian repertories of public song (wangga, yawulyu, 2002) lirrga, and junba), we explore some of the characteristics of song language and the need to extend language documentation To close the Garma Symposium, Mandawuy Yunupingu to include musical and other dimensions of song and Witiyana Marika performed, without further performances. Productive engagements between researchers, comment, two djatpangarri songs—"Gapu" (a song performers and communities in documenting songs can lead to about the tide) and "Cora" (a song about an eponymous revitalisation of interest and their renewed circulation in contemporary media and contexts. -

The Status of Degrees in Warlpiri

The status of degrees in Warlpiri Margit Bowler, UCLA Stanford Fieldwork Group: November 4, 2015 Stanford University Margit Bowler, UCLA The status of degrees in Warlpiri Roadmap Overview of Australian languages & my fieldwork site My methodologies for collecting degree data −! Methodological issues Background on degrees and degree constructions Presentation of Warlpiri data −! Degree data roughly following Beck, et al. (2009) −! Potentially problematic morphemes/constructions What can this tell us about: −! Degrees in Warlpiri? (They do not exist!) Wrap-up Margit Bowler, UCLA The status of degrees in Warlpiri Australian languages 250-300 languages were spoken when Australia was colonized in the late 1700s; ∼100 languages are spoken today (Dixon 2002) −! Of these, only approximately 20 languages have a robust speaker population; Warlpiri has 3,000 speakers Divided into Pama-Nyungan (90% of languages in Australia) versus non-Pama-Nyungan Margit Bowler, UCLA The status of degrees in Warlpiri Common features of Australian languages (Split-)ergativity −! Warlpiri has ergative case marking, roughly accusative agreement marking Highly flexible word order Extensive pro-drop Adjectives pattern morphosyntactically like nouns −! Host case marking, trigger agreement marking, and so on Margit Bowler, UCLA The status of degrees in Warlpiri Yuendumu, NT ∼300km northwest of Alice Springs, NT Population ∼800, around 90% Aboriginal 95% of children at the Yuendumu school speak Warlpiri as a first language Languages spoken include Warlpiri, Pintupi/Luritja, -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 10:48:31PM Via Free Access

journal of language contact 11 (2018) 71-112 brill.com/jlc The Development of Phonological Stratification: Evidence from Stop Voicing Perception in Gurindji Kriol and Roper Kriol Jesse Stewart University of Saskatchewan [email protected] Felicity Meakins University of Queensland [email protected] Cassandra Algy Karungkarni Arts [email protected] Angelina Joshua Ngukurr Language Centre [email protected] Abstract This study tests the effect of multilingualism and language contact on consonant perception. Here, we explore the emergence of phonological stratification using two alternative forced-choice (2afc) identification task experiments to test listener perception of stop voicing with contrasting minimal pairs modified along a 10-step continuum. We examine a unique language ecology consisting of three languages spo- ken in Northern Territory, Australia: Roper Kriol (an English-lexifier creole language), Gurindji (Pama-Nyungan), and Gurindji Kriol (a mixed language derived from Gurindji and Kriol). In addition, this study focuses on three distinct age groups: children (group i, 8>), preteens to middle-aged adults (group ii, 10–58), and older adults (group iii, 65+). Results reveal that both Kriol and Gurindji Kriol listeners in group ii contrast the labial series [p] and [b]. Contrarily, while alveolar [t] and velar [k] were consis- tently identifiable by the majority of participants (74%), their voiced counterparts ([d] and [g]) showed random response patterns by 61% of the participants. Responses © Jesse Stewart et al., 2018 | doi 10.1163/19552629-01101003 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc license at the time of publication. -

Show 2.0 Is Coming to Tennant MAYOR Jeffrey Mclaughlin Said He’S Proud to Announce “Show 2.0” and District Show Society

ENNANT & DISTRICT TIMES SAY NO MORE TO www.tdtimes.com.au | Phone (08) 8962 1040 | Email [email protected] FAMILY VIOLENCE Vol. 45 No. 29 FRIDAY 30 JULY 2021 FREE Nyinkka Nyunyu hosts NAIDOC Week finale o By CATHERINE GRIMLEY TENNANT Creek’s NAIDOC festivities ended on a high note on Saturday with a community gathering at Nyinkka Nyunyu. Tjupi Band played their hearts out for the crowd, even being joined on stage by Mayor Jeffrey McLaughlin, who got a reminder of how long it has been since he played hand drums, and what muscles he needs to use to play them. The bacon and egg sandwiches and coffee were popular, but café workers and volunteers kept the lines moving quickly. With the jumping castle, face painting and even a visit from Donald Duck the kids were able to have a barrel of fun while the adults enjoyed the live music. A great finale to a week of activities that the NAIDOC Committee should be proud of. Turn to pages 10-11 for more photo coverage. Show 2.0 is coming to Tennant MAYOR Jeffrey McLaughlin said he’s proud to announce “Show 2.0” and District Show Society. is coming to Tennant Creek next weekend. “After COVID-19 reached Central Australia and the restrictions hit causing The Show with a difference will include a Sideshow Alley next Friday 6 us to miss out on the annual show, there was a team working to bring it back August. to the Barkly,” he said. Barkly Regional Arts’ annual Desert Harmony Festival, which kicked off “It shows the resilience of the town that was crying out for something to yesterday, will hold the Barkly Area Music Festival (BAMFest) on Saturday celebrate in these troubled times. -

The Economics of Road Transport of Beef Cattle

THE ECONOMICS OF ROAD TRANSPORT OF BEEF CATTLE NORTHERN TERRITORY AND QUEENSLAND CHANNEL COUNTRY BUREAU OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS \CANBERRA! AUSTRALIA C71 A.R.A.PURA SEA S5 CORAL SEA NORTHERN TER,RITOR 441I AND 'go \ COUNTRY DARWIN CHANNEL Area. ! Arnhem Land k OF 124,000 S9.mla Aborig R e ), QUEENSLAND DARWIN 1......../L5 GULF OF (\11 SHOWING CARPENTARIA NUMBERS —Zr 1, AREAS AND CATTLE I A N ---- ) TAKEN AT 30-6-59 IN N:C.AND d.1 31-3-59 IN aLD GULF' &Lam rol VI LO Numbers 193,000 \ )14 LEGEND Ar DISTRIT 91, 200 Sy. mls. ••• The/ Elarkl .'-lc • 'Tx/at:viand ER Area , 94 000'S‘frn Counb-v •• •1 411111' == = == Channal Cattle Numbers •BARKLY• = Fatizning Araas 344,0W •• 4* • # DISTRICT • Tannin! r Desert TABLELANDS, 9.4• • 41" amoowea,1 •• • • Area, :NV44. 211,800Sq./nil -N 4 ••• •Cloncurry ALICE NXil% SOCITIf PACIFIC DISTRI W )• 9uches `N\ OCEAN Cattle \ •Dajarra, -r Number 28,000 •Winbon 4%,,\\ SPRINGS A rn/'27:7 0 liazdonnell Ji Ranges *Alice Springs Longreach Simpson DISTRICT LCaWe Desert Numbers v 27.1000 ITh Musgra Ranges. T ullpq -_,OUNTRY JEJe NuTber4L. S A 42Anc SAE al- (gCDET:DWaD [2 ©MU OniVITELE2 NORTHERN TERRITORY AND QUEENSLAND CHANNEL COUNTRY 1959 BUREAU OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 4. REGISTERED AT THE G.P.O. SYDNEY FOR TRANSMISSION BY POST AS A BOOK PREFACE. The Bureau of Agricultural Economics has undertaken an investigation of the economics of road transport of beef cattle in the remote parts of Australia inadequately served by railways. The survey commenced in 1958 when investigations were carried out in the pastoral areas of Western Australia and a report entitled "The Economics of Road Transport of Beef Cattle - Western Australian Pastoral Areas" was subsequently issued. -

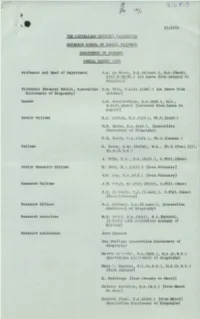

General Editor, Australian Dictionary of Biography

J_ \,. r-- 1 21/1970 RESF.ARCH SCHOOL OF SOCL\1....;s.,ru_~F.S DEPARTMENr OF li1§_TO~~ ANNUAL REPORT J.969 Professor and Head of Department J.A. La N2uz~, B.A.(W.Aust.), M.A.(Oxon), Litt.D. (M2lb.) [on leave from January to t~ov c r.:be r ] Professor (General Editor, Australian D. I-I. Pil:c, D. Litt. (Adel. ) [ on leave from Dictionary of Biography) October] Reader L.F. Fit~h3rdinge, B.A.(Syd.), M.A., B.Li t t .(Oxon) [returned from leave in Aug us t] Senior Fellows R.A. Golian, M. A. ( Syd.), Ph.D.(Lond.) N.B. Nairn, H.A. (Syd.), (Australian Dicti or.ary of Biography) F.B. S:nith, !1. A.(:1e lb.), Ph.D.(Cantab.) Fellows R. KtL.~r, B.Sc.(Delhi), M.A., Ph.D.(Panj.(I)), Ph .D. (A. :q.u,) J. E".!dy, S.J., B.A.(?'ielb.), D.Phil.(Oxon) Senior Research Fellows W. E:i t c , 11. A. {:::lb.) [from February] P.R. 1':'ly, i'1, A. ( n.z. ) [from February] Research Fellows J.H. \1-)igt, D:- . phil.(Ki e l), D.Phil,(Oxon) B. K. c~ Gnis, !1. A. (W,Aust.), D.Phil.(Oxon) [ frc:::i. ;;; ~bruary] Research Officer H.J. Gib~n~y, E.A.(W.Aust:), (Australian Dictfo:,.-1~-y of Diogrnphy) Research Associate M.E. I-:c ~c"l , B.A. (Hull), M.A.(Monash), ( j.:'.in ::::~.y ,;ith /,untralian Academy of Scbr..ce) Research Assistants Joa n Lynra·.m Nan Phillips (Australian Dictionary of Biography) Martha F..c'::!. -

Noun Phrase Constituency in Australian Languages: a Typological Study

Linguistic Typology 2016; 20(1): 25–80 Dana Louagie and Jean-Christophe Verstraete Noun phrase constituency in Australian languages: A typological study DOI 10.1515/lingty-2016-0002 Received July 14, 2015; revised December 17, 2015 Abstract: This article examines whether Australian languages generally lack clear noun phrase structures, as has sometimes been argued in the literature. We break up the notion of NP constituency into a set of concrete typological parameters, and analyse these across a sample of 100 languages, representing a significant portion of diversity on the Australian continent. We show that there is little evidence to support general ideas about the absence of NP structures, and we argue that it makes more sense to typologize languages on the basis of where and how they allow “classic” NP construal, and how this fits into the broader range of construals in the nominal domain. Keywords: Australian languages, constituency, discontinuous constituents, non- configurationality, noun phrase, phrase-marking, phrasehood, syntax, word- marking, word order 1 Introduction It has often been argued that Australian languages show unusual syntactic flexibility in the nominal domain, and may even lack clear noun phrase struc- tures altogether – e. g., in Blake (1983), Heath (1986), Harvey (2001: 112), Evans (2003a: 227–233), Campbell (2006: 57); see also McGregor (1997: 84), Cutfield (2011: 46–50), Nordlinger (2014: 237–241) for overviews and more general dis- cussion of claims to this effect. This idea is based mainly on features -

Highways Byways

Highways AND Byways THE ORIGIN OF TOWNSVILLE STREET NAMES Compiled by John Mathew Townsville Library Service 1995 Revised edition 2008 Acknowledgements Australian War Memorial John Oxley Library Queensland Archives Lands Department James Cook University Library Family History Library Townsville City Council, Planning and Development Services Front Cover Photograph Queensland 1897. Flinders Street Townsville Local History Collection, Citilibraries Townsville Copyright Townsville Library Service 2008 ISBN 0 9578987 54 Page 2 Introduction How many visitors to our City have seen a street sign bearing their family name and wondered who the street was named after? How many students have come to the Library seeking the origin of their street or suburb name? We at the Townsville Library Service were not always able to find the answers and so the idea for Highways and Byways was born. Mr. John Mathew, local historian, retired Town Planner and long time Library supporter, was pressed into service to carry out the research. Since 1988 he has been steadily following leads, discarding red herrings and confirming how our streets got their names. Some remain a mystery and we would love to hear from anyone who has information to share. Where did your street get its name? Originally streets were named by the Council to honour a public figure. As the City grew, street names were and are proposed by developers, checked for duplication and approved by Department of Planning and Development Services. Many suburbs have a theme. For example the City and North Ward areas celebrate famous explorers. The streets of Hyde Park and part of Gulliver are named after London streets and English cities and counties. -

2. Working on the Dictionary

2 Working on the dictionary Rhonda Inkamala Aranda1 Imanka kngarriparta ntjarra purta urrkapumala ngkitja Aranda nurnaka kngartiwuka pa intalhilaka. Ngkitja intalhilakala nhanha nama marra, rilha ntjarrala, artwala, arrkutjala, kitjia itna kaltjirramala ngkitja nurnakanha ritamilatjika, intalhilatjika, kitjia ntjarranha ikarltala kuta kaltjanthitjika. Kuka yatinya ntjarraka pmara ntilatjika, ngkitja Arandala pmara rritnya ilatjika, marna pa tnuntha rilhakanha ingkarraka ntyarra nthitjika. Kaltjala ntama ngkitja nurnakanha ikarlta kuta tnyinatjinanga. Pipa Dictionary nhanhala ngkitja nurnakanha Luritja pa Aranda lhangkarama, nthakanha intalhilatja, ritamilatjika ngkitja nurnakanha ikarlta kuta tnyinatjika. Kwaiya kngarra nuka ‘Nangalanha’ Clara Ngala Inkamala ira imangka urrkaputjarta CAAMA2 Radio Imparja Television—Nganampa Anwernekenhe Language and Culture Programme. Nhanha ntama ngkitja kuka irala ngkama: ‘Ngkitja nurnakanha ilkarlta kuta tnyinatjika’. 1 I choose to use this spelling of our language, because it is phonetic and reflects our history. 2 Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association. 15 CARL STREHLOW’S 1909 ComparatiVE Heritage Dictionary Figure 8: Rhonda Inkamala working at the Strehlow Research Centre, 2017. Source: Adam Macfie, Strehlow Research Centre, Alice Springs. Luritja Irriti Anangu nganampa tjuta tjungungkuya wangka Luritja kampa kutjupa nguru walkatjunu. Wangka nganampa kwarri palya ngaranyi, uwankarrangku ritamilanytjaku walkatjunkunytjaku. Nganampa waltja tjutaya irriti ngurra nyanga tjanala nyinapayi, Ungkungka-la -

A Grammar of Jingulu, an Aboriginal Language of the Northern Territory

A grammar of Jingulu, an Aboriginal language of the Northern Territory Pensalfini, R. A grammar of Jingulu, an Aboriginal language of the Northern Territory. PL-536, xix + 262 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 2003. DOI:10.15144/PL-536.cover ©2003 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Also in Pacific Linguistics John Bowden, 2001, Taba: description of a South Halmahera Austronesian language. Mark Harvey, 2001, A grammar of Limilngan: a language of the Mary River Region, Northern Territory, Allstralia. Margaret Mutu with Ben Telkitutoua, 2002, Ua Pou: aspects of a Marquesan dialect. Elisabeth Patz, 2002, A grammar of the Kukll Yalanji language of north Queensland. Angela Terrill, 2002, Dharumbal: the language of Rockhampton, Australia. Catharina Williams-van Klinken, John Hajek and Rachel Nordlinger, 2002, Tetlin Dili: a grammar of an East Timorese language. Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, southeast and south Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Shldies at the Australian National University. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the school's Department of Linguistics. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise, who are usually not members of the editorial board.