The Reconstruction of Proto-SHWNG Morphology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Languages with Longer Words Have More Lexical Change Søren

Languages with longer words have more lexical change Søren Wichmann and Eric W. Holman 1. Introduction: Aims and data1 The findings to be presented in this paper were not anticipated, but came about as an unexpected result of looking at how the application of a version of the Levenshtein distance to word lists compares with cognate counting. We were interested in the degree to which the two correlate. The results of this investigation are intrinsically interesting and will be presented in the following section 2, but even more interesting is our finding that differ- ences between counting cognates and measuring the Levenshtein distances vary as a function of average word lengths in the word lists compared. This observation will occupy the remainder of the paper, with section 3 devoted to establishing the sta tis tical significance of the observation across language families, while section 4 establishes the significance within language groups, and section 5 discusses competing explanations. First we briefly explain the specific version of the Levenshtein distance used and the concept of cognate identification. In numerous previous papers, beginning in Holman et al. (2008a), the present authors as well as other members of the network of scholars partici- pating in the project known as ASJP (or Automated Similarity Judgment Pro gram) have applied a computer-assisted comparison of word lists in order to derive a measure of differences among languages. Our method consists in comparing pairs of words to determine the Levenshtein distance, LD, which is defined as the number of substitutions, insertions, and deletions necessary to transform one word into another. -

Languages of Irian Jaya: Checklist. Preliminary Classification, Language Maps, Wordlists

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS S elLA..e.� B - No. 3 1 LANGUAGES OF IRIAN JAYA CHECKLIST PRELIMINARY CLASSIFICATION, LANGUAGE MAPS, WORDLISTS by C.L. Voorhoeve Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Voorhoeve, C.L. Languages of Irian Jaya: Checklist. Preliminary classification, language maps, wordlists. B-31, iv + 133 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1975. DOI:10.15144/PL-B31.cover ©1975 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. ------ ---------------------------- PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is published by the Lingui�tic Ci�cte 06 Canbe��a and consists of four series: SERIES A - OCCASIONAL PAPERS SERIES B - MONOGRAPHS SERIES C - BOOKS SERIES V - SPECIAL PU BLICATIONS. EDITOR: S.A. Wurm. ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton. ALL CORRESPONDENCE concerning PACIF IC LINGUISTICS, including orders and subscriptions, should be addressed to: The Secretary, PACIFIC LINGUISTICS, Department of Linguistics, School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, Box 4, P.O., Canberra, A.C.T. 2600 . Australia. Copyright � C.L. Voorhoeve. First published 1975. Reprinted 1980. The editors are indebted to the Australian National University for help in the production of this series. This publication was made possible by an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. National Library of Australia Card Number and ISBN 0 85883 128 7 TAB LE OF CONTENTS -

UNENGAGED BIBLELESS LANGUAGES (UBL List by Languages: ROL) September, 2018

UNENGAGED BIBLELESS LANGUAGES (UBL List by Languages: ROL) September, 2018. Version 1.0 Language ROL # Zones # Countries Country Lang. Population Anambé aan 1 1 Brazil 6 Pará Arára aap 1 1 Brazil 340 Aasáx aas 2 1 Tanzania 350 Mandobo Atas aax 1 1 Indonesia 10,000 Bankon abb 1 1 Cameroon 12,000 Manide abd 1 1 Philippines 3,800 Abai Sungai abf 1 1 Malaysia 500 Abaga abg 1 1 Papua New Guinea 600 Lampung Nyo abl 11 1 Indonesia 180,000 Abaza abq 3 1 Russia 37,800 Pal abw 1 1 Papua New Guinea 1,160 Áncá acb 2 2 Cameroon; Nigeria 300 Eastern Acipa acp 2 1 Nigeria 5,000 Cypriot Arabic acy 1 1 Cyprus 9,760 Adabe adb 1 1 Indonesia 5,000 Andegerebinha adg 2 1 Australia 5 Adonara adr 1 1 Indonesia 98,000 Adnyamathanha adt 1 1 Australia 110 Aduge adu 3 1 Nigeria 1,900 Amundava adw 1 1 Brazil 83 Haeke aek 1 1 New Caledonia 300 Arem aem 3 2 Laos; Vietnam 270 Ambakich aew 1 1 Papua New Guinea 770 Andai afd 1 1 Papua New Guinea 400 Defaka afn 2 1 Nigeria 200 Afro-Seminole Creole afs 3 2 Mexico; United States 200 Afitti aft 1 1 Sudan 4,000 Argobba agj 3 1 Ethiopia 46,940 Agta, Isarog agk 1 1 Philippines 5 Tainae ago 1 1 Papua New Guinea 1,000 Remontado Dumagat agv 3 1 Philippines 2,530 Mt. Iriga Agta agz 1 1 Philippines 1,500 Aghu ahh 1 1 Indonesia 3,000 Aizi, Tiagbamrin ahi 1 1 Côte d'Ivoire 9,000 Aizi, Mobumrin ahm 1 1 Côte d'Ivoire 2,000 Àhàn ahn 2 1 Nigeria 300 Ahtena aht 1 1 United States 45 Ainbai aic 1 1 Papua New Guinea 100 Amara aie 1 1 Papua New Guinea 230 Ai-Cham aih 1 1 China 2,700 Burumakok aip 1 1 Indonesia 40 Aimaq aiq 7 1 Afghanistan 701000 Airoran air 1 1 Indonesia 1,000 Ali aiy 2 2 Central African Republic; Congo Kinshasa 35,000 Aja (Sudan) aja 1 1 South Sudan 200 Akurio ako 2 2 Brazil; Suriname 2 Akhvakh akv 1 1 Russia 210 Alabama akz 1 1 United States 370 Qawasqar alc 1 1 Chile 12 Amaimon ali 1 1 Papua New Guinea 1,780 Amblong alm 1 1 Vanuatu 150 Larike-Wakasihu alo 1 1 Indonesia 12,600 Alutor alr 1 1 Russia 25 UBLs by ROL Page 1 Language ROL # Zones # Countries Country Lang. -

2 the Trans New Guinea Family Andrew Pawley and Harald Hammarström

2 The Trans New Guinea family Andrew Pawley and Harald Hammarström 2.1 Introduction The island of New Guinea is a region of spectacular, deep linguistic diversity.1 It contains roughly 850 languages, which on present evidence fall into at least 18 language families that are not demonstrably related, along with several iso- lates.2 This immense diversity, far greater than that found in the much larger area of Europe, is no doubt mainly a consequence of the fact that New Guinea has been occupied for roughly 50,000 years by peoples organised into small kin-based social groups, lacking overarching political affiliations, and dispersed across a terrain largely dominated by rugged mountains and swampy lowlands, with quite frequent population movements. Among the non-Austronesian families of New Guinea one family stands out for its large membership and wide geographic spread: Trans New Guinea (TNG). With a probable membership of between 300 and 500 discrete languages, plus hundreds of highly divergent dialects, TNG is among the most numerous of the world’s language families.3 TNG languages are spoken from the Bomberai Pen- insula at the western end of mainland New Guinea (132 degrees E) almost to the eastern tip of the island (150 degrees E). Most of the cordillera that runs for more than 2000 kilometers along the centre of New Guinea is occupied exclusively by TNG languages. They are also prominent in much of the lowlands to the south of the cordillera and in patches to the north, especially from central Madang Province eastwards. There are possible outliers spoken on Timor, Alor and Pantar. -

Culture Change, Language Change

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C-120 CULTURE CHANGE, LANGUAGE CHANGE CASE STUDIES FROM MELANESIA edited by Tom Dutton Published with financial assistance from the UNES CO Office for the Pacific Studies Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Dutton, T. editor. Culture change, language change: Case studies from Melanesia. C-120, viii + 164 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1992. DOI:10.15144/PL-C120.cover ©1992 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES C: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurrn EDITORIAL BOARD: K.A. Adelaar, T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIALADVISERS: B.W. Bender K.A. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Instituteof Linguistics David Bradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii Michael G. Clyne P. Miihlhausler Monash University Linacre College, Oxford S.H. Elbert G.N. O' Grady University of Hawaii University of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Franklin K.L. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W. Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W. Grace Gillian Sankoff University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K. Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K. Tsou Harvard University City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. -

Diversification and Change in South Halmahera–West New Guinea

Austronesians in Papua: Diversification and change in South Halmahera–West New Guinea by David Christopher Kamholz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Andrew Garrett, Chair Professor Larry Hyman Professor Johanna Nichols Fall 2014 Austronesians in Papua: Diversification and change in South Halmahera–West New Guinea Copyright 2014 by David Christopher Kamholz 1 Abstract Austronesians in Papua: Diversification and change in South Halmahera–West New Guinea by David Christopher Kamholz Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Andrew Garrett, Chair This dissertation presents a new subgrouping of South Halmahera–West New Guinea (SHWNG) languages. The 38 SHWNG languages form a small, poorly known branch of Austronesian. The Austronesian family originated in Taiwan and later spread into In- donesia, across New Guinea, and to the remote Pacific. In New Guinea, approximately 3500 years ago, Austronesian speakers first came into contact with so-called Papuan languages—the non-Austronesian languages indigenous to New Guinea, comprising more than 20 families. The Austronesian languages still extant from this initial spread into New Guinea fall into two branches: SHWNG and Oceanic. In great contrast to Oceanic, only a few SHWNG languages are well-described, and almost nothing has been reconstructed at the level of Proto-SHWNG. Contact with Papuan languages has given the SHWNG lan- guages a typological profile quite different from their linguistic forebears. Chapter 1 puts the SHWNG languages in context, describing their significance for Aus- tronesian and their broader relevance to historical linguistics. -

Diversification and Change in South-Halmahera-West New Guinea

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Austronesians in Papua: Diversification and Change in South-Halmahera-West New Guinea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6nj8g0b3 Author Kamholz, David Publication Date 2014 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Austronesians in Papua: Diversification and change in South Halmahera–West New Guinea by David Christopher Kamholz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Andrew Garrett, Chair Professor Larry Hyman Professor Johanna Nichols Fall 2014 Austronesians in Papua: Diversification and change in South Halmahera–West New Guinea Copyright 2014 by David Christopher Kamholz 1 Abstract Austronesians in Papua: Diversification and change in South Halmahera–West New Guinea by David Christopher Kamholz Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Andrew Garrett, Chair This dissertation presents a new subgrouping of South Halmahera–West New Guinea (SHWNG) languages. The 38 SHWNG languages form a small, poorly known branch of Austronesian. The Austronesian family originated in Taiwan and later spread into In- donesia, across New Guinea, and to the remote Pacific. In New Guinea, approximately 3500 years ago, Austronesian speakers first came into contact with so-called Papuan languages—the non-Austronesian languages indigenous to New Guinea, comprising more than 20 families. The Austronesian languages still extant from this initial spread into New Guinea fall into two branches: SHWNG and Oceanic. In great contrast to Oceanic, only a few SHWNG languages are well-described, and almost nothing has been reconstructed at the level of Proto-SHWNG. -

Indonesian Linguistigs

Hsiatic Society flDonoorapto VOL. XV AN INTRODUGTION TO INDONESIAN LINGUISTIGS BEING FOUR ESSAYS BY REN WARD BRANDSTETTER, Ph.D. TRANSLATED BY C. O. BLAGDEN, M.A., M.R.A.S. LONDON PUBLISHED BY THE ROYAL ASIATIG SOCIETY 22, ALBEMARLE STREET, W. 1916 PREFACE THE Indonesian languages constitute the Western division of the great Austronesian (or Malayo-Polynesian, or Oceanic) family of speech, which extends over a vast portion of the earth'a surface, bnt has an almost entirely insular domain, reaching as it does from Madagascar, near the coast of Africa, to Easter Island, an outlying dependency of South. America, and from Eormosa and Hawaii in the North to New Zealand in the South. The whole family is of great interest and im- portance from the linguistic point of view and can fairly claim to rank with the great families of speech, such as the Inclo- European, the Semitic, the Ural-Altaie, the Tibeto-Chinese, etc. Th.ou.gh hut a amall part of its area falls on the mainland of Asia, there is no reasonable doubt that it is of genuinely Asiatic origin, and of late years it has been linked up with anotlier Asiatic family, which inoludes a number of the languages of India and Indo-China (e.g., Munda, Khasi, Mon, Khmor, Nicobarese, Sakai, etc.). The Indonesian division of the Austronesian family is the part that has best preserved the traces of its origin, and it forms therefore an essential olue to the study of the family as a whole. It has also been more thoroughly investigated than the other two divisions—viz., the Micronesian and Melanesian group and the Polynesian. -

Wabo. This Language Is Also Called Nusari

TUE LlNGVISTIC SITVATION IN TIIE IS"ANDS OF YAPEN, KVIIVDV, NAV ...fND ItIIOSNVItI. NEW GVIN.A VE RH AN DE LIN GEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL·, LAND· EN VOLKENKUNDE DEEL 35 THE LINGUISTIC SITUA.TION IN THE ISLANDS OF YAPEN, KURUDU, NAU AND MIOSNUM, NEW GUINEA BY J. C. ANCEAUX PUBUCATlON COMMISSIONED AND FINANCED BY TUE GOVEBNMENT OF NETHEBLANDS NE'IV GUINEA 'S·G RA VEN H A G E - MAR TIN U S N U HOF F - 1 96 1 OON.rENTS l. Introduction 1 2. The Sourees 3 3. The Language Map . 6 4. The Comparative Word-List. 13 5. The quantitative Analysis . 80 6. Phonological Relationships 149 7. Verbal Forms 150 8. Elements for indicating personal possession of the parts of the body. .. .... 157 9. Elements to indicate possession with regard to kinship terms. 163 Language Map at the end of the volume. ~---------- --- ------,\ \\ ~~ ....... A \ \ ~~ \ ~~.... e .. \ <R.......... ,.... " ..e. \ A- Biak B- Waropen ----____4:2_, C-Mor ',------------------ D- Wandamen E- Dusner ~ F- Ron G- Meoswar H -Irarutu Geelvink Boy .......... / .... ,;' / / / / /B" / " / ,," &0 / / Sketch Map , ____ -1 I IIU:.rtt.. / / of the • I cvt9J' !;.:.-J I Geelvink Bay Area ~_J. (Scale 1 : 2.350.000) Indicated are the areas of the languages used for comparison. -r. 1. INTRODUu.nON Relatively little is known about the languages spoken on and around the island of Yapen. The published sources contain little more than a few brief word-lists, although there is more material to be found in manuscript form. This includes, for example, the lexicographical and other notes on the Yava language (especially of the Mantembu dialect) by Dominee 1. -

Language and Power Among Language Speaking Communities in North of Papua, Indonesia

- International Refereed Social Sciences Journal DOI : 10.18843/rwjasc/v11i1/01 DOI URL : http://dx.doi.org/10.18843/rwjasc/v11i1/01 Language and Power among Language Speaking Communities in North of Papua, Indonesia Hendrik Arwam, Yusuf W. Sawaki,* Faculty of Letters and Culture Faculty of Letters and Culture University of Papua University of Papua Manokwari, Papua Barat, Indonesia Manokwari, Papua Barat, Indonesia *(Corresponding Author) ABSTRACT The article aims at describing the interrelated factors between language and power among language speaking communities in Papua, Indonesia. It focuses on the connection between language use and unequal relation among language speaking communities in West Papua, Indonesia, especially among Biak, Wandamen and Waropen speaking groups and other small- size speech communities. In terms of ecology of language in Papua, the diverse linguistic situation is equal to the diversity of language speech communities in different ecological environment. Besides, the diversity of languages is also contributed by the diversity of non- linguistic factors such as imbalances in economic, social, politic, and cultural powers. This condition creates unequal power among language speaking communities living closed to each other that has a connection to language use. Language use provides evidence between language and power between more dominant speech communities and less dominant ones. Thus, this creates sociolinguistic phenomena such as multilingualism, lingua franca, language shift, and language endangerment. Keywords: Language and power, language use, non-linguistic factors, language speaking community, Papua, Indonesia. INTRODUCTION: Language may not be just defined as a linguistic phenomenon, but it can be also defined as a social behavior or social activity in which a language speaking community used to express their social identity and social status (Krauss and Chiu 1998; Fairclough 1989; Bourdieu 1991; Sawaki and Arwam 2018). -

Innovative Numerals in Malayo- Polynesian Languages Outside of Oceania

Innovative numerals in Malayo- Polynesian languages outside of Oceania Antoinette Schappera & Harald Hammarströmb Leiden Universitya, Universität zu Kölna, Radboud Universityb & Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropologyb In this paper we seek to draw attention to Malayo- Polynesian languages outside of the Oceanic subgroup with innovative bases and complex numerals involving various additive, subtractive and multiplicative procedures. We highlight that the number of languages showing such innovations is more than previously recognised in the literature. Finally, we observe that the concentration of complex numeral innovations in the region of eastern Indonesia suggests Papuan influence, either through contact or substrate. However, we also note that socio-cultural factors, in the form of numeral taboos and conventionalised counting practices, may have played a role in driving innovations in numerals. 1. INTRODUCTION1 There has been much discussion of the developments in innovative numeral formations in Oceanic languages. Galis (1960) observed that many AN languages to the north of New Guinea have exchanged the ancestral decimal system for various quinary systems. More recently, Dunn et al. (2008:739) observed that the decimal system in their sample of 22 western Oceanic languages was not very stable, having changed in almost half the languages to quinary systems. Blust (2009:274) suggests that the emergence of such different numeral systems in Oceanic languages is due to intensive contact and trading between Austronesian and Papuan language-speaking peoples. Smith (1988:51-53) similarly observed that counting systems were not particularly stable due to trading and exchange relations between AN and Papuan language speaking peoples in Morobe province of Papua New Guinea. -

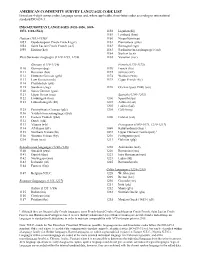

American Community Survey Language Code List

AMERICAN COMMUNITY SURVEY LANGUAGE CODE LIST Listed are 4-digit census codes, language names and, where applicable, three-letter codes according to international standard ISO 639-3. INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES (1053-1056, 1069- 1073, 1110-1564) 1158 Ligurian (lij) 1159 Lombard (lmo) Haitian (1053-1056)1 1160 Neapolitan (nap) 1053 Guadeloupean Creole French (gcf) 1161 Piemontese (pms) 1054 Saint Lucian Creole French (acf) 1162 Romagnol (rgn) 1055 Haitian (hat) 1163 Sardinian (macrolanguage) (srd) 1164 Sicilian (scn) West Germanic languages (1110-1139, 1234) 1165 Venetian (vec) German (1110-1124) French (1170-1175) 1110 German (deu) 1170 French (fra) 1111 Bavarian (bar) 1172 Jèrriais (nrf) 1112 Hutterite German (geh) 1174 Walloon (wln) 1113 Low German (nds) 1175 Cajun French (frc) 1114 Plautdietsch (ptd) 1115 Swabian (swg) 1176 Occitan (post 1500) (oci) 1120 Swiss German (gsw) 1121 Upper Saxon (sxu) Spanish (1200-1205) 1122 Limburgish (lim) 1200 Spanish (spa) 1123 Luxembourgish (ltz) 1201 Asturian (ast) 1202 Ladino (lad) 1125 Pennsylvania German (pdc) 1205 Caló (rmq) 1130 Yiddish (macrolanguage) (yid) 1131 Eastern Yiddish (ydd) 1206 Catalan (cat) 1132 Dutch (nld) 1133 Vlaams (vls) Portuguese (1069-1073, 1210-1217) 1134 Afrikaans (afr) 1069 Kabuverdianu (kea) 1 1135 Northern Frisian (frr) 1072 Upper Guinea Crioulo (pov) 1 1136 Western Frisian (fry) 1210 Portuguese (por) 1234 Scots (sco) 1211 Galician (glg) Scandinavian languages (1140-1146) 1218 Aromanian (aen) 1140 Swedish (swe) 1220 Romanian (ron) 1141 Danish (dan) 1221 Istro Romanian (ruo)