Borrowed Color and Flora/Fauna Terminology in Northwest New Guinea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Linguistic Background to SE Asian Sea Nomadism

The linguistic background to SE Asian sea nomadism Chapter in: Sea nomads of SE Asia past and present. Bérénice Bellina, Roger M. Blench & Jean-Christophe Galipaud eds. Singapore: NUS Press. Roger Blench McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Department of History, University of Jos Correspondence to: 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: Cambridge, March 21, 2017 Roger Blench Linguistic context of SE Asian sea peoples Submission version TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. The broad picture 3 3. The Samalic [Bajau] languages 4 4. The Orang Laut languages 5 5. The Andaman Sea languages 6 6. The Vezo hypothesis 9 7. Should we include river nomads? 10 8. Boat-people along the coast of China 10 9. Historical interpretation 11 References 13 TABLES Table 1. Linguistic affiliation of sea nomad populations 3 Table 2. Sailfish in Moklen/Moken 7 Table 3. Big-eye scad in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 4. Lake → ocean in Moklen 8 Table 5. Gill-net in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 6. Hearth on boat in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 7. Fishtrap in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 8. ‘Bracelet’ in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 9. Vezo fish names and their corresponding Malayopolynesian etymologies 9 FIGURES Figure 1. The Samalic languages 5 Figure 2. Schematic model of trade mosaic in the trans-Isthmian region 12 PHOTOS Photo 1. Orang Laut settlement in Riau 5 Photo 2. -

A History of Fruits on the Southeast Asian Mainland

OFFPRINT A history of fruits on the Southeast Asian mainland Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation Cambridge, UK E-mail: [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Occasional Paper 4 Linguistics, Archaeology and the Human Past Edited by Toshiki OSADA and Akinori UESUGI Indus Project Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto, Japan 2008 ISBN 978-4-902325-33-1 A history of Fruits on the Southeast Asian mainland A history of fruits on the Southeast Asian mainland Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation Cambridge, UK E-mail: [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm ABSTRACT The paper presents an overview of the history of the principal tree fruits grown on the Southeast Asian mainland, making use of data from biogeography, archaeobotany, iconography and linguistics. Many assertions in the literature about the origins of particular species are found to be without empirical basis. In the absence of other data, comparative linguistics is an important source for tracing the spread of some fruits. Contrary to the Pacific, it seems that many of the fruits we now consider characteristic of the region may well have spread in recent times. INTRODUCTION empirical base for Pacific languages is not matched for mainland phyla such as Austroasiatic, Daic, Sino- This study 1) is intended to complement a previous Tibetan or Hmong-Mien, so accounts based purely paper on the history of tree-fruits in island Southeast on Austronesian tend to give a one-sided picture. Asia and the Pacific (Blench 2005). Arboriculture Although occasional detailed accounts of individual is very neglected in comparison to other types of languages exist (e.g. -

In Antoinette SCHAPPER, Ed., Contact and Substrate in the Languages of Wallacea PART 1

Contact and substrate in the languages of Wallacea: Introduction Antoinette SCHAPPER KITLV & University of Cologne 1. What is Wallacea?1 The term “Wallacea” originally refers to a zoogeographical area located between the ancient continents of Sundaland (the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Borneo, Java, and Bali) and Sahul (Australia and New Guinea) (Dickerson 1928). Wallacea includes Sulawesi, Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores, Sumba, Timor, Halmahera, Buru, Seram, and many smaller islands of eastern Indonesia and independent Timor-Leste (Map 1). What characterises this region is its diverse biota drawn from both the Southeast Asian and Australian areas. This volume uses the term Wallacea to refer to a linguistic area (Schapper 2015). In linguistic terms as in biogeography, Wallacea constitutes a transition zone, a region in which we observe the progression attenuation of the Southeast Asian linguistic type to that of a Melanesian linguistic type (Gil 2015). Centred further to the east than Biological Wallacea, Linguistic Wallacea takes in the Papuan and Austronesian languages in the region of eastern Nusantara including the Minor Sundic Islands east of Lombok, Timor-Leste, Maluku, the Bird’s Head and Neck of New Guinea, and Cenderawasih Bay (Map 2). Map 1. Biological Wallacea Map 2. Linguistic Wallacea 1 My editing and research for this issue has been supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research VENI project “The evolution of the lexicon. Explorations in lexical stability, semantic shift and borrowing in a Papuan language family” and by the Volkswagen Stiftung DoBeS project “Aru languages documentation”. Many thanks to Asako Shiohara and Yanti for giving me the opportunity to work with them on editing this NUSA special issue. -

The Status of the Least Documented Language Families in the World

Vol. 4 (2010), pp. 177-212 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4478 The status of the least documented language families in the world Harald Hammarström Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig This paper aims to list all known language families that are not yet extinct and all of whose member languages are very poorly documented, i.e., less than a sketch grammar’s worth of data has been collected. It explains what constitutes a valid family, what amount and kinds of documentary data are sufficient, when a language is considered extinct, and more. It is hoped that the survey will be useful in setting priorities for documenta- tion fieldwork, in particular for those documentation efforts whose underlying goal is to understand linguistic diversity. 1. InTroducTIon. There are several legitimate reasons for pursuing language documen- tation (cf. Krauss 2007 for a fuller discussion).1 Perhaps the most important reason is for the benefit of the speaker community itself (see Voort 2007 for some clear examples). Another reason is that it contributes to linguistic theory: if we understand the limits and distribution of diversity of the world’s languages, we can formulate and provide evidence for statements about the nature of language (Brenzinger 2007; Hyman 2003; Evans 2009; Harrison 2007). From the latter perspective, it is especially interesting to document lan- guages that are the most divergent from ones that are well-documented—in other words, those that belong to unrelated families. I have conducted a survey of the documentation of the language families of the world, and in this paper, I will list the least-documented ones. -

Tangguh LNG Project in Indonesia

Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Tangguh LNG Project in Indonesia June 2005 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 April 2005) Currency Unit – rupiah (Rp) Rp1.00 = $0.000105 $1.00 = Rp9,488 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AMDAL – analisis mengenai dampak lingkungan (environmental impact analysis system) ANDAL – analisis dampak lingkungan (environmental impact analysis ) BOD – biochemical oxygen demand CI – Conservation International COD – chemical oxygen demand DAV – directly affected village DGS – diversified growth strategy EPC – engineering, procurement, and construction GDA – global development alliance GHG – green house gas HDD – horizontal directional drilling JNCC – Joint Nature Conservation Committee KJP – A consortium of Kellogg Brown and Root–JGC–Pertafinikki LARAP – land acquisition and resettlement action plan (ADB terminology for equivalent document is involuntary resettlement plan) LNG – liquefied natural gas MARPOL – International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Convention Ships (1973) MBAS – methylene blue active substances MODU – mobile offshore drilling unit MOE – Ministry of Environment NGO non government organization PSC – production-sharing contract RKL – rencana pengelolaan lingkungan (environmental management plan) RPL – rencana pemantauan lingkungan (environmental monitoring plan) SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment TMRC – Tanah Merah resettlement committee TNC – The Nature Conservancy TSS – total suspended solid UNDP – United Nations Development Programme USAID – United State -

Special Issue 2012 Part I ISSN: 0023-1959

Language & Linguistics in Melanesia Special Issue 2012 Part I ISSN: 0023-1959 Journal of the Linguistic Society of Papua New Guinea ISSN: 0023-1959 Special Issue 2012 Harald Hammarström & Wilco van den Heuvel (eds.) History, contact and classification of Papuan languages Part One Language & Linguistics in Melanesia Special Issue 2012 Part I ISSN: 0023-1959 THE KEUW ISOLATE: PRELIMINARY MATERIALS AND CLASSIFICATION David Kamholz University of California, Berkeley [email protected] ABSTRACT Keuw is a poorly documented language spoken by less than 100 people in southeast Cenderawasih Bay. This paper gives some preliminary data on Keuw, based on a few days of field work. Keuw is phonologically similar to Lakes Plain languages: it lacks contrastive nasals and has at least two tones. Basic word order is SOV. Lexical comparison with surrounding languages suggests that Keuw is best classified as an isolate. Keywords: Keuw, Kehu, Papua, Indonesia, New Guinea, isolate, description, classification 1 INTRODUCTION Keuw (ISO 639-3 khh, also known as Kehu or Keu) is a poorly documented language spoken by a small ethnic group of the same name in southeast Cenderawasih Bay. Keuw territory is located in a swampy lowland plain along the Poronai river in Wapoga distrct, Nabire regency, Papua province, Indonesia (see Figure 1 and 2). The Keuw are reported to be in occasional contact with the Burate (bti, East Geelvink Bay family), who live downstream near the mouth of the Poronai (village: Totoberi), and the Dao/Maniwo (daz, Paniai Lakes family), who live upstream in the highlands (village: Taumi). There is no known contact with other nearby ethnic groups, which include a group of Waropen (wrp, Austronesian) who live just south of the Burate (village: Samanui), and the Auye (auu, Paniai Lakes family), who live in the highlands along the Siriwo river. -

Language Documentation in Papua: the State of the Art

18/02/2012 Language Documentation in Papua: The state of the art Apriani Arilaha, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Novita Ndiken, Sutriani Narfafan 276 languages presented by according to Nikolaus P. Himmelmann Ethnologue Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/ Known Problems of Language Listings 1. Language/dialect distinction, here particularly relevant for Asmat, Dani, Yali, Irires 2. Data quality (alternate names, census = 38% of all info, maps, etc) languages 3. Inclusion of regional and national spoken in languages, e.g. Papua Malay (not Indonesia (276 of 726) included, but 4 kinds of Malay in Maluku, 2 in NTT, 2 in Sulawesi) Older Listings SHWNG: West New Guinea (34) Oceanic: Sarmi Jayapura Bay (14) Voorhoeve (1975): 199 languages (many ? with various dialects) Silzer & Heikkinen (1984): 230 languages and 10 major varieties (mostly Dani and Asmat). Hays 2003 – papuaweb.org: 269 languages (based also mostly on Ethnologue) CMP: Bomberai Austronesian (56) North/South (5) 1 18/02/2012 Papuan Languages (220) Speaker numbers Lakes Plain (20) Tor Kwerba (24) Largest, smallest, mean, median Trans‐New Guinea (93) Administrative structure of Irian Jaya before Sociopolitical Setting 1998 (?): 1 Province, 12 Kabupaten Kab. Biak Numfor Accelerating change in the last 150 years: Kab. Manokwari Kab. Sorong Kab. Yapen Waropen - Christian mission since 1855, last ‘first’ Kab. Jayapura Kab. Nabire contacts in the late 1970s Kab. Puncak Jaya Kab. Fakfak Kab. Paniai - Dutch colonial rule 1898 till 1962 Kab. Jayawijaya Kab. Mimika - Indonesiasikan 1962-1998 Kab. Merauke - Otonomi daerah 2001-?? PROVINSI PAPUA Demographic change Population figures 1988/2010 2010 1988 Papua Papua Barat (Irian Jaya) Rural Urban Rural Urban PROVINSI PAPUA BARAT 2.097.752 735.629 532.659 227.763 2.833.381 760.422 Now 2 Provinces with all 1,452,900 3,593,803 together 28 Kabupaten (19 Kabupaten in Papua and 9 Kabupaten in Papua Barat). -

IMS Data Reference Tables

IMS REFERENCE DATA – VERSION 1.7 TABLES 1. Substance .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Local Authority ....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 3. Drug Action Team (DAT) ...................................................................................................................................................... 13 4. Nationality ........................................................................................................................................................................... 17 5. Ethnicity ............................................................................................................................................................................... 22 6. Sexual Orientation ............................................................................................................................................................... 22 7. Religion or Belief .................................................................................................................................................................. 22 8. Employment Status .............................................................................................................................................................. 23 9. Accommodation Status -

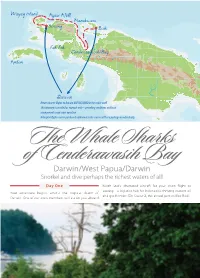

Darwin/West Papua/Darwin Snorkel and Dive Perhaps the Richest Waters of All!

Wayag Island Ayau Atoll Manokwari Sorong Biak Fak Fak Cenderawasih Bay Ambon Darwin Return charter flights ex Darwin ARE INCLUDED in the cruise tariff. This itinerary is provided as example only – prevailing conditions and local arrangements may cause variation. Helicopter flights can be purchased additional to the cruise tariff as a package or individually. TheWhale Sharks of Cenderawasih Bay Darwin/West Papua/Darwin Snorkel and dive perhaps the richest waters of all! Day One North Star’s chartered aircraft for your short flight to Sorong – a logistics hub for Indonesia’s thriving eastern oil Your adventure begins amidst the tropical charm of and gas frontier (On Cruise 2, the arrival port will be Biak). Darwin. One of our crew members will escort you aboard Sorong is also where we will welcome you aboard the spearfishing to collecting eatable worms from the magnificent TRUE NORTH. powdery-white sand beaches. The atoll is surrounded by crystal clear water that is frequented by large pods of Enjoy a welcome aboard cocktail as we begin to cruise dolphins. The outer-reef drops sharply to over 1000m and through the equally magnificent Raja Ampat archipelago. clouds of beautiful fishes carpet the reef walls. We’ll have Located off the northwest tip of Bird’s Head Peninsula a chance to snorkel and dive at several sites around the on the island of New Guinea, in Indonesia’s West Papua atoll, or you can head off to the big-blue (outside the Ayau province, Raja Ampat, or the Four Kings, is an archipelago Marine Park) to try your luck at some deep water trolling. -

Constructing a Narrative Discourse in Iau

Iau Narrative Discourse CONSTRUCTING A NARRATIVE DISCOURSE IN IAU . with updated appendices- By Janet Bateman Draft-Final copy for comment only not to be quoted Summer Institute of Linguistics Original paper in cooperation with Universitas Cenderawasih Jayapura, Irian Jaya INDONESIA Original from Ivan Lowe Workshop (1984?85?) with subsequent revisions from 1998-2006 Submitted to Mike Moxness Jan 2006 Updated appendices 2020 1 Contents Iau Narrative Discourse CONSTRUCTING A NARRATIVE DISCOURSE IN IAU . with updated appendices- ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 Introduction to Iau ................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Language Classification ................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Language Characteristics . ................................................................................................................ 3 2.0 The Data Base....................................................................................................................................... 4 3.0 Titles and Openings .............................................................................................................................. 6 3.1Titles ................................................................................................................................................. -

The West Papua Dilemma Leslie B

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2010 The West Papua dilemma Leslie B. Rollings University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rollings, Leslie B., The West Papua dilemma, Master of Arts thesis, University of Wollongong. School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2010. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3276 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. School of History and Politics University of Wollongong THE WEST PAPUA DILEMMA Leslie B. Rollings This Thesis is presented for Degree of Master of Arts - Research University of Wollongong December 2010 For Adam who provided the inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION................................................................................................................................ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... iii Figure 1. Map of West Papua......................................................................................................v SUMMARY OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 -

The Malayic-Speaking Orang Laut Dialects and Directions for Research

KARLWacana ANDERBECK Vol. 14 No., The 2 Malayic-speaking(October 2012): 265–312Orang Laut 265 The Malayic-speaking Orang Laut Dialects and directions for research KARL ANDERBECK Abstract Southeast Asia is home to many distinct groups of sea nomads, some of which are known collectively as Orang (Suku) Laut. Those located between Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula are all Malayic-speaking. Information about their speech is paltry and scattered; while starting points are provided in publications such as Skeat and Blagden (1906), Kähler (1946a, b, 1960), Sopher (1977: 178–180), Kadir et al. (1986), Stokhof (1987), and Collins (1988, 1995), a comprehensive account and description of Malayic Sea Tribe lects has not been provided to date. This study brings together disparate sources, including a bit of original research, to sketch a unified linguistic picture and point the way for further investigation. While much is still unknown, this paper demonstrates relationships within and between individual Sea Tribe varieties and neighbouring canonical Malay lects. It is proposed that Sea Tribe lects can be assigned to four groupings: Kedah, Riau Islands, Duano, and Sekak. Keywords Malay, Malayic, Orang Laut, Suku Laut, Sea Tribes, sea nomads, dialectology, historical linguistics, language vitality, endangerment, Skeat and Blagden, Holle. 1 Introduction Sometime in the tenth century AD, a pair of ships follows the monsoons to the southeast coast of Sumatra. Their desire: to trade for its famed aromatic resins and gold. Threading their way through the numerous straits, the ships’ path is a dangerous one, filled with rocky shoals and lurking raiders. Only one vessel reaches its destination.