Personal Information As a Historical Source Using the Example of the Estonian and Other Baltic Diasporas in Kazakhstan1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sairan Bayandinova Zheken Mamutov Gulnura Issanova Man-Made Ecology of East Kazakhstan Environmental Science and Engineering

Environmental Science Sairan Bayandinova Zheken Mamutov Gulnura Issanova Man-Made Ecology of East Kazakhstan Environmental Science and Engineering Environmental Science Series editors Ulrich Förstner, Hamburg, Germany Wim H. Rulkens, Wageningen, The Netherlands Wim Salomons, Haren, The Netherlands More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/3234 Sairan Bayandinova • Zheken Mamutov Gulnura Issanova Man-Made Ecology of East Kazakhstan 123 Sairan Bayandinova Gulnura Issanova Faculty of Geography and Environmental Research Center of Ecology Sciences and Environment of Central Asia Al-Farabi Kazakh National University (Almaty), State Key Laboratory of Desert Almaty and Oasis Ecology, Xinjiang Institute Kazakhstan of Ecology and Geography Chinese Academy of Sciences Zheken Mamutov Urumqi Faculty of Geography and Environmental China Sciences Al-Farabi Kazakh National University and Almaty Kazakhstan U.U. Uspanov Kazakh Research Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry Almaty Kazakhstan ISSN 1863-5520 ISSN 1863-5539 (electronic) Environmental Science and Engineering ISSN 1431-6250 Environmental Science ISBN 978-981-10-6345-9 ISBN 978-981-10-6346-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6346-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017950252 © Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. -

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

2 (3)/2017 Scientific Journal “Fundamentalis Scientiam” (Madrid, Spain)

№2 (3)/2017 Scientific journal “Fundamentalis scientiam” (Madrid, Spain) ISSN 0378-5955 The journal is registered and published in Spain It is published 12 times a year. Articles are accepted in Spanish, Polish, English, Russian, Ukrainian, German, French languages for publication. Scientific journal “Fundamentalis scientiam” (lat. “Basic Science”) was established in Spain in the autumn of 2016. Its goal is attracting the masses to the interest of “knowledge.” We have immediately decided to grow to the international level, namely to bond the scientists of the Eurasian continent under the aegis of the common work, by filling the journal with research materials, articles, and results of work. Editorial board: Chief editor: Petr Novotný – Palacky University, Olomouc Managing editor: Lukáš Procházka – Jan Evangelista Purkyně University in Ústí nad Labem, Ústí nad Labem Petrenko Vladislav, PhD in geography, lecturer in social and economic geography. (Kiev, Ukraine) Andrea Biyanchi – University of Pavia, Pavia Bence Kovács – University of Szeged, Szeged Franz Gruber – University of Karl and Franz, Graz Jean Thomas – University of Limoges, Limoges Igor Frennen – Politechnika Krakowska im. Tadeusza Kościuszki Plaza Santa Maria Soledad Torres Acosta, Madrid, 28004 E-mai: [email protected] Web: www.fundamentalis-scientiam.com CONTENT CULTURAL SCIENCES Tattigul Kartaeva, Ainur Yermekbayeva THE SEMANTICS OF THE CHEST IN KAZAKH CULTURE .................................................................. 4 ECONOMICS Khakhonova N.N. INTERCONNECTION OF ACCOUNTING SYSTEMS IN THE COMPANY MANAGEMENT ...................................................... 10 HISTORICAL SCIENCES Bexeitov G.T., Satayeva B.E. Kunanbaeva A. СURRENT CONDITION AND RESEARCH SYSTEM FEEDS KAZAKHS .................................. 25 PROBLEMS OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL Eleuov Madiyar, Moldakhmet Arkhad EXCAVATIONS CONDUCTED WERE MADE IN MEDIEVAL SITE UTYRTOBE .............................. 28 THE MONUMENTS OF NEAR THE LOCATION– RAKHAT IN 2015 (ALMATY) .............................. -

Investor's Atlas 2006

INVESTOR’S ATLAS 2006 Investor’s ATLAS Contents Akmola Region ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Aktobe Region .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 Almaty Region ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Atyrau Region .............................................................................................................................................................. 17 Eastern Kazakhstan Region............................................................................................................................................. 20 Karaganda Region ........................................................................................................................................................ 24 Kostanai Region ........................................................................................................................................................... 28 Kyzylorda Region .......................................................................................................................................................... 31 Mangistau Region ........................................................................................................................................................ -

The Anguish of Repatriation. Immigration to Poland And

EEPXXX10.1177/0888325414532494East European Politics and SocietiesGrzymała-Kazłowska and Grzymała-Moszczyńska 532494research-article2014 East European Politics and Societies and Cultures Volume XX Number X Month 201X 1 –21 © 2014 SAGE Publications The Anguish of Repatriation: 10.1177/0888325414532494 http://eeps.sagepub.com hosted at Immigration to Poland and Integration http://online.sagepub.com of Polish Descendants from Kazakhstan Aleksandra Grzymała-Kazłowska University of Warsaw Halina Grzymała-Moszczyńska Jagiellonian University Repatriation remains an unsolved problem of Polish migration policy. To date, it has taken place on a small scale, mostly outside of the state’s repatriation system. Thousands of people with a promised repatriation visa are still waiting to be repatri- ated. The majority of the repatriates come from Kazakhstan, home to the largest popu- lation of descendants of Poles in the Asian part of the former USSR. They come to Poland not only for sentimental reasons, but also in search of better living conditions. However, repatriates—in particular older ones—experience a number of problems with adaptation in Poland, dominated by financial and housing-related issues. A further source of difficulties for repatriates, alongside their spatial dispersion, insufficient lin- guistic and cultural competencies, and identity problems, is finding a place on and adapting to the Polish labor market. Despite their difficult situation and special needs, the repatriates in Poland are not sufficiently supported due to the inefficiency of admin- istration and non-governmental institutions dealing with the task of repatriates’ integration. It results in the anguish of repatriation. Keywords: repatriation; repatriates from Kazakhstan; Polish integration policy; immigration to Poland; Polish minority in the former USSR Introduction Over two decades after the beginning of the transformation of the political and economic system in Poland, repatriation remains an unresolved issue. -

Zhanat Kundakbayeva the HISTORY of KAZAKHSTAN FROM

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN THE AL-FARABI KAZAKH NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Zhanat Kundakbayeva THE HISTORY OF KAZAKHSTAN FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO PRESENT TIME VOLUME I FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO 1991 Almaty "Кazakh University" 2016 ББК 63.2 (3) К 88 Recommended for publication by Academic Council of the al-Faraby Kazakh National University’s History, Ethnology and Archeology Faculty and the decision of the Editorial-Publishing Council R e v i e w e r s: doctor of historical sciences, professor G.Habizhanova, doctor of historical sciences, B. Zhanguttin, doctor of historical sciences, professor K. Alimgazinov Kundakbayeva Zh. K 88 The History of Kazakhstan from the Earliest Period to Present time. Volume I: from Earliest period to 1991. Textbook. – Almaty: "Кazakh University", 2016. - &&&& p. ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 In first volume of the History of Kazakhstan for the students of non-historical specialties has been provided extensive materials on the history of present-day territory of Kazakhstan from the earliest period to 1991. Here found their reflection both recent developments on Kazakhstan history studies, primary sources evidences, teaching materials, control questions that help students understand better the course. Many of the disputable issues of the times are given in the historiographical view. The textbook is designed for students, teachers, undergraduates, and all, who are interested in the history of the Kazakhstan. ББК 63.3(5Каз)я72 ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 © Kundakbayeva Zhanat, 2016 © al-Faraby KazNU, 2016 INTRODUCTION Данное учебное пособие is intended to be a generally understandable and clearly organized outline of historical processes taken place on the present day territory of Kazakhstan since pre-historic time. -

Kristian Nilsen (University Centre in Svalbard, Norway) Arne Jensen

№3/2017 VOL.2 Norwegian Journal of development of the International Science ISSN 3453-9875 It was established in November 2016 with support from the Norwegian Academy of Science. DESCRIPTION The Scientific journal “Norwegian Journal of development of the International Science” is issued 12 times a year and is a scientific publication on topical problems of science. Editor in chief – Karin Kristiansen (University of Oslo, Norway) The assistant of theeditor in chief – Olof Hansen James Smith (University of Birmingham, UK) Kristian Nilsen (University Centre in Svalbard, Norway) Arne Jensen (Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway) Sander Svein (University of Tromso, Norway) Lena Meyer (University of Gothenburg, Sweden) Hans Rasmussen (University of Southern Denmark, Denmark) Chantal Girard (ESC Rennes School of Business, France) Ann Claes (University of Groningen, Netherlands) Ingrid Karlsen (University of Oslo, Norway) Terje Gruterson (Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Norway) Sander Langfjord (University Hospital, Norway) Fredrik Mardosas (Oslo and Akershus University College, Norway) Emil Berger (Ministry of Agriculture and Food, Norway) Sofie Olsen (BioFokus, Norway) Rolf Ulrich Becker (University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany) Lutz Jancke (University of Zurich, Switzerland) Elizabeth Davies (University of Glasgow, UK) Chan Jiang(Peking University, China) 1000 copies Norwegian Journal of development of the International Science Iduns gate 4A, 0178, Oslo, Norway email: [email protected] site: http://www.njd-iscience.com CONTENT ECONOMIC SCIENCES Yerzhanova S., Romanko E., Mambetova S. Osipova E., Danilov A. ASSESSMENT OF CURRENT TRENDS OF METHODICAL RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF INVESTMENT ACTIVITY IN ASSESSMENT OF EFFICIENCY OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN ............. 4 PARTNERSHIP OF UNIVERSITY SCIENCE AND THE INDUSTRIAL COMPANIES DURING Zhukova O. -

Situation of Polish Deportees in Kazakhstan in the Post-War Period

Положение польских спецпоселенцев в Казахстане ... N.V.Stepanenko Situation of Polish deportees in Kazakhstan in the post-war period The article refers to the Polish deportees remaining in the territory of Kazakhstan after signing of the Soviet — Polish agreement on July 6, 1945. The main reasons on which the Polish deportees could not be deported to their homeland are specified. By the example of Kokchetau region as the most populated in post-war peri- od presented the work on involvement of Polish deportees in public life of Kazakhstan. The author emphasiz- es that the Poles left after re-evacuation consisted the Polish population of Kazakhstan and until 1956 their position was determined by the decree of the Council of People's Commissars dated January 8, 1945 «On the legal status of deportees». References У 1 Kalishevsky M. «Polonia» in the East: About the history of the Polish diaspora in Central Asia / M.Kalishevsky, M.: Nauka, 2009, р. 180. 2 Kazakh SSR NKVD information as of 7 January 1946 on applications and volunteers to get out of Soviet citizenshipГ /Central State Archive of RoK. fond p. 1137. finding aid 18. file 139 l. Р. 32. 3 Resolution of the Ministry of Education of the Kazakh SSR on sending to homeland of Polish children leftр in orphanages and in the settlement of the citizens (October, 1947) /Central State Archive of RoK. fond p. 1692. finding aid 1. file 1258. Р.154. 4 Information about the recent repatriation of Polish children home /Central State Archive of RoK. fond p. 1987. finding aid 1, 45. -

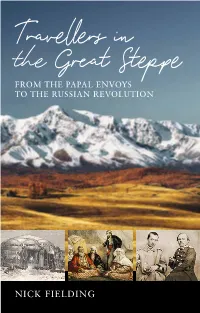

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Lake Dynamics in Central

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Lake dynamics in Central Asia in the past 30 years A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Geography by Shengan Zhan 2020 © Copyright by Shengan Zhan 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Lake dynamics in Central Asia in the past 30 years by Shengan Zhan Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor Dennis P. Lettenmaier, Co-Chair Professor Yongwei Sheng, Co-Chair Water is a key resource in arid Central Asia (CA) and is heavily affected by climate change and human activities. Temperature across the region has increased drastically especially in the mountain region while precipitation change is less homogeneous. The increased temperature has caused increased melting of glacier and snow which has a large contribution to the runoff in rivers. Human activities such as agriculture irrigation and reservoir management also affect water availability. In the Soviet era, agriculture in CA expanded continuously and large amount of water was extracted from rivers for irrigation. This has caused the catastrophic decline of the Aral Sea. In the post-Soviet era, countries in CA have reorganized their agriculture structure to be self- sufficient. It is important to understand how these changes affect water availability in CA especially under climate change. This dissertation uses lakes as proxy indicators of water ii availability and assesses how climate and human activities have affected lakes in CA. Seventeen lakes located in three former Soviet republics and western China from seven basins are examined using remote sensing and hydrologic modeling to estimate their changes in area, water level and volume. -

Jilili Abuduwaili · Gulnura Issanova Galymzhan Saparov Hydrology and Limnology of Central Asia Water Resources Development and Management

Water Resources Development and Management Jilili Abuduwaili · Gulnura Issanova Galymzhan Saparov Hydrology and Limnology of Central Asia Water Resources Development and Management Series editors Asit K. Biswas, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore Cecilia Tortajada, Institute of Water Policy, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore Editorial Board Dogan Altinbilek, Ankara, Turkey Francisco González-Gómez, Granada, Spain Chennat Gopalakrishnan, Honolulu, USA James Horne, Canberra, Australia David J. Molden, Kathmandu, Nepal Olli Varis, Helsinki, Finland Hao Wang, Beijing, China [email protected] More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/7009 [email protected] Jilili Abuduwaili • Gulnura Issanova Galymzhan Saparov Hydrology and Limnology of Central Asia 123 [email protected] Jilili Abuduwaili and State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology Faculty of Geography and Environmental and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences Sciences Al-Farabi Kazakh National University Urumqi Almaty China Kazakhstan and and Research Centre of Ecology and Research Centre of Ecology and Environment of Central Asia (Almaty) Environment of Central Asia (Almaty) Almaty Almaty Kazakhstan Kazakhstan Gulnura Issanova Galymzhan Saparov State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Research Centre of Ecology and Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology Environment of Central Asia (Almaty) and Geography, Chinese Academy of U.U. Uspanov Kazakh Research Institute of Sciences Soil Science and Agrochemistry Urumqi Almaty China Kazakhstan ISSN 1614-810X ISSN 2198-316X (electronic) Water Resources Development and Management ISBN 978-981-13-0928-1 ISBN 978-981-13-0929-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0929-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018943710 © Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. -

ASTRA Salvensis, Supplement No. 1/2021 561 HISTORY of POLE

ASTRA Salvensis, Supplement no. 1/2021 HISTORY OF POLE DIASPORA (ХІХ-ХХІ) Kanat A. YENSENOV1, Zhamilya M.-A. ASSYLBEKOVA2, Saule Z. MALIKOVA3,4, Krykbai M. ALDABERGENOV5, Bekmurat R. NAIMANBAYEV6 1Department of Source Studies, Historiography and Kazakhstan History, Institute of State History, Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic, Nur-Sultan, Republic of Kazakhstan 2Department of Social Sciences and Humanities, University of International Business, Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan 3North Kazakhstan State Regional Archive, Petropavlovsk, Republic of Kazakhstan 4Department of Kazakhstan History and Political – Social Sciences, M. Kozibayev North Kazakhstan State University, Petropavlovsk, Republic of Kazakhstan 5Department of Printing and Publishing, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Nur-Sultan, Republic of Kazakhstan 6Department of History of Kazakhstan and Geography, Silkway International University, Shymkent, Republic of Kazakhstan Abstract: This scientific research reports about destiny and history of Polish Diaspora in Kazakhstan. For example, it considers the start of Polish locating during the Russian Empire in the XIX century in the territory of Kazakhstan, the participation of the Polish nationality in the life of Kazakh people, the deportation of the Poles to Kazakhstan in 1936 in the period of the Soviet Union in the XX century, their location in the regions, difficulties in the history of the homeland, and the involvement in the development of the Republic Industry and virgin lands campaign. Moreover, the data are provided on the restoration of the Poles' rights in 1956 and their migrations to Poland were provided. In addition, the paper informs about the life of Polish Diaspora in Kazakhstan in the XXI century, their contributions for the development of the republic and the foundation and functioning of the “Kazakhstan Poles Union”, created in 1992, their political stability and interethnic accord with the people of Kazakhstan, population, location and activities of Polish originated people.