The Exeter Blitz Information for Teachers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War II

World War II. – “The Blitz“ This information report describes the events of “The Blitz” during the Second World War in London. The attacks between 7th September 1940 and 10 th May 1941 are known as “The Blitz”. The report is based upon information from http://www.secondworldwar.co.uk/ , http://www.worldwar2database.com/ and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Blitz . Prelude to the War in London The Second World War started on 1 st September 1939 with the German attack on Poland. The War in London began nearly one year later. On 24 th August 1940 the German Air Force flew an attack against Thames Haven, whereby some German bombers dropped bombs on London. At this time London was not officially a target of the German Air Force. As a return, the Royal Air Force attacked Berlin. On 5th September 1940 Hitler ordered his troops to attack London by day and by night. It was the beginning of the Second World War in London. Attack on Thames Haven in 1940 The Attacks First phase The first phase of the Second World War in London was from early September 1940 to mid November 1940. In this first phase of the Second World War Hitler achieved great military success. Hitler planned to destroy the Royal Air Force to achieve his goal of British invasion. His instruction of a sustainable bombing of London and other major cities like Birmingham and Manchester began towards the end of the Battle of Britain, which the British won. Hitler ordered the German Air Force to switch their attention from the Royal Air Force to urban centres of industrial and political significance. -

The Blitz and Its Legacy

THE BLITZ AND ITS LEGACY 3 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2010 PORTLAND HALL, LITTLE TITCHFIELD STREET, LONDON W1W 7UW ABSTRACTS Conference organised by Dr Mark Clapson, University of Westminster Professor Peter Larkham, Birmingham City University (Re)planning the Metropolis: Process and Product in the Post-War London David Adams and Peter J Larkham Birmingham City University [email protected] [email protected] London, by far the UK’s largest city, was both its worst-damaged city during the Second World War and also was clearly suffering from significant pre-war social, economic and physical problems. As in many places, the wartime damage was seized upon as the opportunity to replan, sometimes radically, at all scales from the City core to the county and region. The hierarchy of plans thus produced, especially those by Abercrombie, is often celebrated as ‘models’, cited as being highly influential in shaping post-war planning thought and practice, and innovative. But much critical attention has also focused on the proposed physical product, especially the seductively-illustrated but flawed beaux-arts street layouts of the Royal Academy plans. Reconstruction-era replanning has been the focus of much attention over the past two decades, and it is appropriate now to re-consider the London experience in the light of our more detailed knowledge of processes and plans elsewhere in the UK. This paper therefore evaluates the London plan hierarchy in terms of process, using new biographical work on some of the authors together with archival research; product, examining exactly what was proposed, and the extent to which the different plans and different levels in the spatial planning hierarchy were integrated; and impact, particularly in terms of how concepts developed (or perhaps more accurately promoted) in the London plans influenced subsequent plans and planning in the UK. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

February, 1955

Library of The Harvard Musical Association Bulletin No. 23 February, 1955 Library Committee CHARLES R. NUTTER JOHN N. BURK RICHARD G. APPEL CYRUS DURGIN RUDOLPH ELIE Director of the Library and Library and Custodian of the Marsh Room Marsh Room Marsh Room CHARLES R. NUTTER MURIEL FRENCH FLORENCE C. ALLEN To the Members of the Association: Your attention is called to an article in this issue by Albert C. Koch. * * * * REPORT ON THE LIBRARY AND ON THE MARSH ROOM FOR THE YEAR 1954 To the President and the Directors of The Harvard Musical Association: Today, when television and the radio, both A.M. and F.M., are providing much of the intellectual sustenance for the common man and woman, the individual who turns for an intellectual repast to the writers of past centuries and also tries to phrase his thoughts both vocal and written with some regard to the rules of grammar and the principles of rhetoric is regarded as high‐brow and is thrown out of society. I am aware that I lay myself open to the charge of being a high‐brow, a charge that creates no reactionary emotion at all, especially as it comes usually from the low‐brow, and that I may be thrown out of society into a lower stratum, when I state that for the text of this report I have turned to a gentleman whose mortal life spanned the years between 1672 and 1719. Even the low‐brow has probably heard or read the name Joseph Addison, though it may convey nothing to him except the fact that it has an English and not a foreign sound. -

The Belfast Blitz

The Belfast Blitz Blitz is short for ‘Blitzkrieg’ which is the German word for a lightning war. It was named after the bombs, light flashes and the noise of the German bomber planes in the Second World War. Belfast was one of the most bombed cities in the UK. The worst attacks were on 15th April 1941 and 4th May 1941. Unprepared James Craig (Lord Craigavon) was prime minister of Northern Ireland and was responsible for preparing Belfast for any attacks by the German ‘Luftwaffe’. He and his team did very little to prepare the city for the bombings. In fact, they even forgot to tell the army that an attack might happen! Belfast was completely unprepared for the Blitz. Belfast had a large number of people living in the city but it had very few air raid shelters. There were only 200 public shelters in the whole of Belfast for everyone to share. Searchlights were designed to scan the sky for bombing aircrafts. However, they were not even set up before the attacks began. The Germans were much better prepared. They knew Belfast was not ready for them. They choose seven targets to hit: Belfast Power Station, Belfast Waterworks, Connswater Gasworks, Harland and Wolff Shipyards, Rank and Co. Mill, Short’s Aircraft Factory and Victoria Barracks. Why Was Belfast Attacked? Belfast was famous and still is famous for ship building and aircraft building. At the time of the Blitz, the Harland and Wolff shipyards were some of the largest in the world. There were over 3,000 ships in the Belfast docks area and the Germans wanted to destroy them. -

The Axis Advances

wh07_te_ch17_s02_MOD_s.fm Page 568 Monday, March 12, 2007 2:32WH07MOD_se_CH17_s02_s.fm PM Page 568 Monday, January 29, 2007 6:01 PM Step-by-Step German fighter plane SECTION Instruction 2 WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO Objectives Janina’s War Story As you teach this section, keep students “ It was 10:30 in the morning and I was helping my focused on the following objectives to help mother and a servant girl with bags and baskets as them answer the Section Focus Question they set out for the market. Suddenly the high- and master core content. pitch scream of diving planes caused everyone to 2 freeze. Countless explosions shook our house ■ Describe how the Axis powers came to followed by the rat-tat-tat of strafing machine control much of Europe, but failed to guns. We could only stare at each other in horror. conquer Britain. Later reports would confirm that several German Janina Sulkowska in ■ Summarize Germany’s invasion of the the early 1930s Stukas had screamed out of a blue sky and . Soviet Union. dropped several bombs along the main street— and then returned to strafe the market. The carnage ■ Understand the horror of the genocide was terrible. the Nazis committed. —Janina Sulkowska,” Krzemieniec, Poland, ■ Describe the role of the United States September 12, 1939 before and after joining World War II. Focus Question Which regions were attacked and occupied by the Axis powers, and what was life like under their occupation? Prepare to Read The Axis Advances Build Background Knowledge L3 Objectives Diplomacy and compromise had not satisfied the Axis powers’ Remind students that the German attack • Describe how the Axis powers came to control hunger for empire. -

New Editions 2012

January – February 2013 Volume 2, Number 5 New Editions 2012: Reviews and Listings of Important Prints and Editions from Around the World • New Section: <100 Faye Hirsch on Nicole Eisenman • Wade Guyton OS at the Whitney • Zarina: Paper Like Skin • Superstorm Sandy • News History. Analysis. Criticism. Reviews. News. Art in Print. In print and online. www.artinprint.org Subscribe to Art in Print. January – February 2013 In This Issue Volume 2, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Visibility Associate Publisher New Editions 2012 Index 3 Julie Bernatz Managing Editor Faye Hirsch 4 Annkathrin Murray Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prodigiously Associate Editor Amelia Ishmael New Editions 2012 Reviews A–Z 10 Design Director <100 42 Skip Langer Design Associate Exhibition Reviews Raymond Hayen Charles Schultz 44 Wade Guyton OS M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp 46 Zarina: Paper Like Skin New Editions Listings 48 News of the Print World 58 Superstorm Sandy 62 Contributors 68 Membership Subscription Form 70 Cover Image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, I Am Busy (2012), 100% cotton towel. Published by WOW (Works on Whatever), New York, NY. Photo: James Ewing, courtesy Art Production Fund. This page: Barbara Takenaga, detail of Day for Night, State I (2012), aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite and white ground with hand coloring by the artist. Printed and published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, NH. Art in Print 3500 N. Lake Shore Drive Suite 10A Chicago, IL 60657-1927 www.artinprint.org [email protected] No part of this periodical may be published without the written consent of the publisher. -

Downloads of Technical Information

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Nuclear Spaces: Simulations of Nuclear Warfare in Film, by the Numbers, and on the Atomic Battlefield Donald J. Kinney Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES NUCLEAR SPACES: SIMULATIONS OF NUCLEAR WARFARE IN FILM, BY THE NUMBERS, AND ON THE ATOMIC BATTLEFIELD By DONALD J KINNEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Donald J. Kinney defended this dissertation on October 15, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Dissertation Joseph R. Hellweg University Representative Jonathan A. Grant Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member Guenter Kurt Piehler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Morgan, Nala, Sebastian, Eliza, John, James, and Annette, who all took their turns on watch as I worked. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Kris Harper, Jonathan Grant, Kurt Piehler, and Joseph Hellweg. I would especially like to thank Ron Doel, without whom none of this would have been possible. It has been a very long road since that afternoon in Powell's City of Books, but Ron made certain that I did not despair. Thank you. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract..............................................................................................................................................................vii 1. -

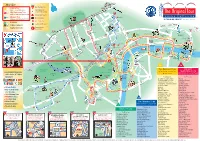

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Exeter Blitz for Adobe

Devon Libraries Exeter Blitz Factsheet 17 On the night of 3 rd - 4 th of May 1942, Exeter suffered its most destructive air raid of the Second World War. 160 high explosive bombs and 10,000 incendiary devices were dropped on the city. The damage inflicted changed the face of the city centre forever. Exeter suffered nineteen air raids between August 1940 and May 1942. The first was on the night of 7 th – 8 th of August 1940, when a single German bomber dropped five high explosive bombs on St. Thomas. Luckily no one was hurt and the damage was slight. The first fatalities were believed to have been in a raid on 17 th September 1940, when a house in Blackboy Road was destroyed, killing four boys. In most of the early raids it is likely that the city was not the intended target. The Luftwaffe flew over Exeter on its way towards the industrial cities to the north. It is possible that these earlier attacks on Exeter were caused by German bombers jettisoning unused bombs on the city when returning from raiding these industrial targets. It was not until the raids of 1942 that Exeter was to become the intended target. The town of Lubeck is a port on the Baltic; it had fine medieval architecture reflecting its wealth and importance. Although it was used to supply the German army and had munitions factories on the outskirts of the town, it was strategically unimportant. The bombing of this town on the night of 28 th – 29 th March on the orders of Bomber Command is said to be the reason why revenge attacks were carried out on ‘some of the most beautiful towns in England’. -

2007 Lnstim D'hi,Stoire Du Temp

WORLD "TAR 1~WO STlIDIES ASSOCIATION (formerly American Committee on the History ofthe Second World War) Mark P. l'arilIo. Chai""an Jona:han Berhow Dl:pat1menlofHi«ory E1izavcla Zbeganioa 208 Eisenhower Hall Associare Editors KaDsas State University Dct>artment ofHistory Manhattan, Knnsas 66506-1002 208' Eisenhower HnJl 785-532-0374 Kansas Stale Univemty rax 785-532-7004 Manhattan, Kansas 66506-1002 parlllo@,'<su.edu Archives: Permanent Directors InstitlJle for Military History and 20" Cent'lly Studies a,arie, F. Delzell 22 J Eisenhower F.all Vandcrbijt Fai"ersity NEWSLETTER Kansas State Uoiversit'j Manhattan, Kansas 66506-1002 Donald S. Detwiler ISSN 0885·-5668 Southern Ulinoi' Va,,,,,,,sity The WWT&« is a.fIi!iilI.etf witJr: at Ccrbomlale American Riston:a1 A."-'iociatioG 400 I" Street, SE. T.!rms expiring 100(, Washingtoo, D.C. 20003 http://www.theah2.or9 Call Boyd Old Dominio" Uaiversity Comite internationa: dlli.loire de la Deuxii:me G""",, Mondiale AI"".nde< CochrnIl Nos. 77 & 78 Spring & Fall 2007 lnstiM d'Hi,stoire du Temp. PreSeDt. Carli5te D2I"n!-:'ks, Pa (Centre nat.onal de I. recberche ,sci,,,,tifiqu', [CNRSJ) Roj' K. I'M' Ecole Normale S<rpeneure de Cach411 v"U. Crucis, N.C. 61, avenue du Pr.~j~'>Ut WiJso~ 94235 Cacllan Cedex, ::'C3nce Jolm Lewis Gaddis Yale Universit}' h<mtlJletor MUitary HL'mry and 10'" CenJury Sllldie" lIt Robin HiRbam Contents KaIUa.r Stare Universjly which su!'prt. Kansas Sl.ll1e Uni ....ersity the WWTSA's w-'bs;te ":1 the !nero.. at the following ~ljjrlrcs:;: (URL;: Richa.il E. Kaun www.k··stare.eDu/his.tD.-y/instltu..:..; (luive,.,,)' of North Carolw.