Revival After the Great War Rebuild, Remember, Repair, Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quiet on the French Front”: the First World War Centenary in France and the Challenges of Republican Consensus

Comillas Journal of International Relations | nº 02 | 086-099 [2015] [ISSN 2386-5776] 86 DOI: cir.i02.y2015.007 “All QuieT ON THE FRENCH Front”: THE FIRST WORLD WAR CENTENARY IN FRANCE AND THE CHALLENGES OF REPUBLICAN CONSENSUS «Sin novedad en el frente»: el centenario de la Primera Guerra Mundial en Francia y los desafíos al Consenso Republicano Karine Varley University of Strathclyde Autores School of Humanities & Social Sciences E-mail: [email protected] The 2014 centenary commemorations of the First World War in France were described by many commentators as being marked by a level of consensus that stood in marked contrast Resumen with the broader political environment and the divisive memories of the Second World War. Yet despite shared desires to honour the poilu as a symbol of the sacrifices of all French soldiers, this article argues that the appearance of consensus masks deeper tensions between memories of the First World War and the ideas and values underpinning the French Republic. During the war and the period thereafter, myths of the nation in arms served to legitimise the mobilisation and immense sacrifices of the French people. The wars of the French Revolution had establis- hed the notion of the responsibility of the French people to defend their country, creating a close connection between military service, citizenship and membership of the nation. However, these ideas were challenged by memories of the mutinies of 1917 and of the punishment of those who had disobeyed orders. Having long been excluded from official commemorations, in 2014 the French government sought to rehabilitate the memory of the soldiers shot as an exam- ple for committing acts of disobedience, espionage and criminal offences. -

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

No Goose Step at the Cenotaph

,m,^M,w,m^«««^,,mr,'.^,:>-., .'.^^.^^•^.^n^'y^^, »g^y=^^^i^:^3,..^ i».s^-^^.^:n>.««».a»siBai AJ R Information Volume XLIX No. 6 June 1994 £3 (to non-members) Don't miss . The debate about German participation in the VE Day anniversary Controversial corridors p3 No goose step at the Cenotaph Before the anticlimax pl2 he proposed participation of German soldiers To reiterate these facts is not to rehearse the "let's- Musical in ceremonies on the 50th anniversary of VE be-beastly-to-the-Hun" theme beloved of the late midsummer Day is fuelling widespread and bitter debate. Lord Vansittart and currently echoed in sections of madness p. 16 T Amid the clash of contending opinions one truth the tabloid press. The Nazified Wehrmacht did not stands out beyond peradventure. The German army stand in direct line of succession to the Junker-led that surrendered in May 1945 had been an enthusi Prussian Army. Readers familiar with The Case of astic - and, at the very least, a supremely acquiescent Sergeant Grisha will have recognised the bourgeois- — instrument in Hitler's war of conquest. Buoyed up descended Ludendorff figure responsible for Grisha's The by the euphoria of early victories, it had helped inflict execution in the novel as a precursor of Manstein and unprecedented suffering on millions of Poles, Jews, Keitel in the Second World War. imperative Russians and other Europeans. In fact it was largely from the Junker class the that of Justice I German officers had shown none of their Italian opponents of Hitler who engineered the Officers' Plot counterparts' scruples about despatching Jews to of 20 July 1944 came. -

A Brief History of War Memorial Design

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR MEMORIAL DESIGN War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR MEMORIAL DESIGN war memorial may take many forms, though for most people the first thing that comes to mind is probably a freestanding monument, whether more sculptural (such as a human figure) or architectural (such as an arch or obelisk). AOther likely possibilities include buildings (functional—such as a community hall or even a hockey rink—or symbolic), institutions (such as a hospital or endowed nursing position), fountains or gardens. Today, in the 21st century West, we usually think of a war memorial as intended primarily to commemorate the sacrifice and memorialize the names of individuals who went to war (most often as combatants, but also as medical or other personnel), and particularly those who were injured or killed. We generally expect these memorials to include a list or lists of names, and the conflicts in which those remembered were involved—perhaps even individual battle sites. This is a comparatively modern phenomenon, however; the ancestors of this type of memorial were designed most often to celebrate a victory, and made no mention of individual sacrifice. Particularly recent is the notion that the names of the rank and file, and not just officers, should be set down for remembrance. A Brief History of War Memorial Design 1 War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy Ancient Precedents The war memorials familiar at first hand to Canadians are most likely those erected in the years after the end of the First World War. Their most well‐known distant ancestors came from ancient Rome, and many (though by no means all) 20th‐century monuments derive their basic forms from those of the ancient world. -

February, 1955

Library of The Harvard Musical Association Bulletin No. 23 February, 1955 Library Committee CHARLES R. NUTTER JOHN N. BURK RICHARD G. APPEL CYRUS DURGIN RUDOLPH ELIE Director of the Library and Library and Custodian of the Marsh Room Marsh Room Marsh Room CHARLES R. NUTTER MURIEL FRENCH FLORENCE C. ALLEN To the Members of the Association: Your attention is called to an article in this issue by Albert C. Koch. * * * * REPORT ON THE LIBRARY AND ON THE MARSH ROOM FOR THE YEAR 1954 To the President and the Directors of The Harvard Musical Association: Today, when television and the radio, both A.M. and F.M., are providing much of the intellectual sustenance for the common man and woman, the individual who turns for an intellectual repast to the writers of past centuries and also tries to phrase his thoughts both vocal and written with some regard to the rules of grammar and the principles of rhetoric is regarded as high‐brow and is thrown out of society. I am aware that I lay myself open to the charge of being a high‐brow, a charge that creates no reactionary emotion at all, especially as it comes usually from the low‐brow, and that I may be thrown out of society into a lower stratum, when I state that for the text of this report I have turned to a gentleman whose mortal life spanned the years between 1672 and 1719. Even the low‐brow has probably heard or read the name Joseph Addison, though it may convey nothing to him except the fact that it has an English and not a foreign sound. -

BULGARIA and HUNGARY in the FIRST WORLD WAR: a VIEW from the 21ST CENTURY 21St -Century Studies in Humanities

BULGARIA AND HUNGARY IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR: A VIEW FROM THE 21ST CENTURY 21st -Century Studies in Humanities Editor: Pál Fodor Research Centre for the Humanities Budapest–Sofia, 2020 BULGARIA AND HUNGARY IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR: A VIEW FROM THE 21ST CENTURY Editors GÁBOR DEMETER CSABA KATONA PENKA PEYKOVSKA Research Centre for the Humanities Budapest–Sofia, 2020 Technical editor: Judit Lakatos Language editor: David Robert Evans Translated by: Jason Vincz, Bálint Radó, Péter Szőnyi, and Gábor Demeter Lectored by László Bíró (HAS RCH, senior research fellow) The volume was supported by theBulgarian–Hungarian History Commission and realized within the framework of the project entitled “Peripheries of Empires and Nation States in the 17th–20th Century Central and Southeast Europe. Power, Institutions, Society, Adaptation”. Supported by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences NKFI-EPR K 113004, East-Central European Nationalisms During the First World War NKFI FK 128 978 Knowledge, Lanscape, Nation and Empire ISBN: 978-963-416-198-1 (Institute of History – Research Center for the Humanities) ISBN: 978-954-2903-36-9 (Institute for Historical Studies – BAS) HU ISSN 2630-8827 Cover: “A Momentary View of Europe”. German caricature propaganda map, 1915. Published by the Research Centre for the Humanities Responsible editor: Pál Fodor Prepress preparation: Institute of History, RCH, Research Assistance Team Leader: Éva Kovács Cover design: Bence Marafkó Page layout: Bence Marafkó Printed in Hungary by Prime Rate Kft., Budapest CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................... 9 Zoltán Oszkár Szőts and Gábor Demeter THE CAUSES OF THE OUTBREAK OF WORLD WAR I AND THEIR REPRESENTATION IN SERBIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY .................................. 25 Krisztián Csaplár-Degovics ISTVÁN TISZA’S POLICY TOWARDS THE GERMAN ALLIANCE AND AGAINST GERMAN INFLUENCE IN THE YEARS OF THE GREAT WAR................................ -

New Editions 2012

January – February 2013 Volume 2, Number 5 New Editions 2012: Reviews and Listings of Important Prints and Editions from Around the World • New Section: <100 Faye Hirsch on Nicole Eisenman • Wade Guyton OS at the Whitney • Zarina: Paper Like Skin • Superstorm Sandy • News History. Analysis. Criticism. Reviews. News. Art in Print. In print and online. www.artinprint.org Subscribe to Art in Print. January – February 2013 In This Issue Volume 2, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Visibility Associate Publisher New Editions 2012 Index 3 Julie Bernatz Managing Editor Faye Hirsch 4 Annkathrin Murray Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prodigiously Associate Editor Amelia Ishmael New Editions 2012 Reviews A–Z 10 Design Director <100 42 Skip Langer Design Associate Exhibition Reviews Raymond Hayen Charles Schultz 44 Wade Guyton OS M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp 46 Zarina: Paper Like Skin New Editions Listings 48 News of the Print World 58 Superstorm Sandy 62 Contributors 68 Membership Subscription Form 70 Cover Image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, I Am Busy (2012), 100% cotton towel. Published by WOW (Works on Whatever), New York, NY. Photo: James Ewing, courtesy Art Production Fund. This page: Barbara Takenaga, detail of Day for Night, State I (2012), aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite and white ground with hand coloring by the artist. Printed and published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, NH. Art in Print 3500 N. Lake Shore Drive Suite 10A Chicago, IL 60657-1927 www.artinprint.org [email protected] No part of this periodical may be published without the written consent of the publisher. -

VOL.40 No.4 APRIL 1985 (PDF) Download

MONTHLY JOUffNAL CF THE 2/4 INFANTRY BATTALION ASSOCIATION -----i PATRON: Major Genera! Sir Ivan Dougherty, C.B.E.. D.S.O. & Bar. E D., B.Ec.. LL.D (Hon.) I 40th Year of continuous publication fi ^SK. Registered by:- Australia Post Publication NAS1532. Price:- 50c per copy VoluBe 46 Ho. 4 Month:- April t985. President: Alf Carpenter 66 Chatham Rd, Georgetown 2298 Ph. 049-671969 Vice-Presidents: Senior Allen Lindsay 21a Mirral Rd, Caringbah 2229 02- 5241937 Queensland Laurie hcCosker 60 Hillsdon Rd, Tarlnga 4O66 07-3701395 Far Nth Coast Allan Kirk 1?9 Dibbs St, Lismore 248O 066-214464 Northern JISW £sca Riordan 111 Kemp St, Kempsey 244O 065-624671 Newcastle George Mitchell 6 verll Place Waratab 2298 049-672182 Southern NSW Artie Kleem 5 Karabah Awe, Young 2594 063-822461 Victoria Claude Raymond 92 Rose St, West Coburg 3058 03- 3541145 Sth Australia Peter Denver 15 Admiral Terrace Qoolwa 5214 O85-552252 West Australia Doug Slinger 53 Botham St Bayswater 6053 09-2717027 Committee: Cec Chrystal,Ferd Pegg, Ken Kesteven MC, John Hawkins, Ted Fox, Harry Wright, Worm Aubereon, George Stack, ecretary: Fred Staggs 13 Seven Hills Rd, Seven Hills 2147 02-6711765 .set. Secy: John Meehan 5/23 Dine St, Randwick 2031 02-3999606 Treasurer: Allen Lindsay 21a Mirral Rd, Caringbah 2229 02-5241937 Editor! Laurie Waterhouse 34 Milford Rd, Miranda 2228 02-5242114 Welfare Officer: Harry Wright 3 Boundary Rd, Carlingford 2118 02-8715312 Liaison Officer to the Gallipoli Memorial Club: Athol Heath 02-4514466 NEXT MLETIHQ. The next regular monthly meeting will be held on Tuesday, 28th MAY. -

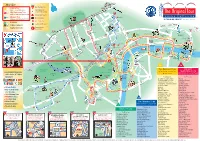

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

Les Monuments Aux Morts De La Grande Guerre Dans Le Nord-Pas-De-Calais

MOSAÏQUE, revue de jeunes chercheurs en SHS – Lille Nord de France – Belgique – n° 14, décembre 2014 Matthias MEIRLAEN Témoins de mémoires spécifiques : les monuments aux morts de la Grande Guerre dans le Nord-Pas-de-Calais Notice Biographique Matthias Meirlaen est docteur de l’université de Louvain (KU Leuven, Belgique), avec un travail portant sur l’émergence de l’enseignement de l’histoire dans les Pays-Bas méridionaux aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. Actuellement, il est Post-doctorant à l’Institut de Recherches Historiques du SePtentrion (IRHiS) de l’Université Lille 3 (France). Il y conduit un Projet de recherches intitulé « Retracer la Grande Guerre » sous la direction d’Élise Julien. Dans son contenu, le Projet ambitionne de s’attarder sur l’ensemble des phénomènes de la mémoire de la Première Guerre mondiale dans la région Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Résumé Dans l’entre-deux-guerres, un vaste mouvement commémoratif se développe. Presque chaque commune de France commémore alors ses morts tombés Pendant la Grande Guerre. Dans la majorité des communes, les manifestations en l’honneur des morts se déroulent autour de monuments érigés Pour l’occasion. cet article examine les représentations Portées Par les monuments communaux de la Première Guerre mondiale dans la région Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Cette région constitue du Point de vue de la guerre un esPace charnière spécifique. APrès les batailles d’octobre 1914, elle est partagée pour quatre années en trois zones distinctes : une zone de front, une zone occupée et une zone libre. L’article cherche à voir si les rePrésentations Portées Par les monuments aux morts de l’entre-deux- guerres diffèrent dans les trois secteurs concernés. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

The War to End All Wars. COMMEMORATIVE

FALL 2014 BEFORE THE NEW AGE and the New Frontier and the New Deal, before Roy Rogers and John Wayne and Tom Mix, before Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse and Felix the Cat, before the TVA and TV and radio and the Radio Flyer, before The Grapes of Wrath and Gone with the Wind and The Jazz Singer, before the CIA and the FBI and the WPA, before airlines and airmail and air conditioning, before LBJ and JFK and FDR, before the Space Shuttle and Sputnik and the Hindenburg and the Spirit of St. Louis, before the Greed Decade and the Me Decade and the Summer of Love and the Great Depression and Prohibition, before Yuppies and Hippies and Okies and Flappers, before Saigon and Inchon and Nuremberg and Pearl Harbor and Weimar, before Ho and Mao and Chiang, before MP3s and CDs and LPs, before Martin Luther King and Thurgood Marshall and Jackie Robinson, before the pill and Pampers and penicillin, before GI surgery and GI Joe and the GI Bill, before AFDC and HUD and Welfare and Medicare and Social Security, before Super Glue and titanium and Lucite, before the Sears Tower and the Twin Towers and the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, before the In Crowd and the A Train and the Lost Generation, before the Blue Angels and Rhythm & Blues and Rhapsody in Blue, before Tupperware and the refrigerator and the automatic transmission and the aerosol can and the Band-Aid and nylon and the ballpoint pen and sliced bread, before the Iraq War and the Gulf War and the Cold War and the Vietnam War and the Korean War and the Second World War, there was the First World War, World War I, The Great War, The War to End All Wars.