Commando 14/08/2012 13:40 Page Iii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amnesty International Report 2014/15 the State of the World's Human Rights

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL OF THE WORLD’S HUMAN RIGHTS THE STATE REPORT 2014/15 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL REPORT 2014/15 THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S HUMAN RIGHTS The Amnesty International Report 2014/15 documents the state of human rights in 160 countries and territories during 2014. Some key events from 2013 are also reported. While 2014 saw violent conflict and the failure of many governments to safeguard the rights and safety of civilians, significant progress was also witnessed in the safeguarding and securing of certain human rights. Key anniversaries, including the commemoration of the Bhopal gas leak in 1984 and the Rwanda genocide in 1994, as well as reflections on 30 years since the adoption of the UN Convention against Torture, reminded us that while leaps forward have been made, there is still work to be done to ensure justice for victims and survivors of grave abuses. AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL This report also celebrates those who stand up REPORT 2014/15 for human rights across the world, often in difficult and dangerous circumstances. It represents Amnesty International’s key concerns throughout 2014/15 the world, and is essential reading for policy- THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S makers, activists and anyone with an interest in human rights. HUMAN RIGHTS Work with us at amnesty.org AIR_2014/15_cover_final.indd All Pages 23/01/2015 15:04 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. -

International Co-Operation in the Use of Elite Military

INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATION IN THE USE OF ELITE MILITARY FORCES TO COUNTER TERRORISM: THE BRITISH AND AMERICAN EXPERIENCE, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THEIR RESPECTIVE EXPERIENCES IN THE EVOLUTION OF LOW-INTENSITY OPERATIONS BY JOSEPH PAUL DE BOUCHERVILLE TAILLON A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE LONDON, ENGLAND, 1992 UMI Number: U615541 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615541 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7 0 XJl\lbj6S3 ABSTRACT J. Paul de B. Taillon "International Co-operation in the Employment of Elite Military Forces to Counter-Terrorism: The British and American Experience With Special Reference to Their Respective Experiences in the Evolution of Low-Intensity Operations." This thesis examines the employment of elite military forces in low-intensity and counter-terrorist operations, and in particular, placing the principal emphasis on the aspect of international co-operation in the latter. The experiences of Great Britain and the United States in such operations are the main elements of the discussion, reflecting their heavy involvement in such operations. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Commando Country Special training centres in the Scottish highlands, 1940-45. Stuart Allan PhD (by Research Publications) The University of Edinburgh 2011 This review and the associated published work submitted (S. Allan, 2007. Commando Country. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Publishing) have been composed by me, are my own work, and have not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Stuart Allan 11 April 2011 2 CONTENTS Abstract 4 Critical review Background to the research 5 Historiography 9 Research strategy and fieldwork 25 Sources and interpretation 31 The Scottish perspective 42 Impact 52 Bibliography 56 Appendix: Commando Country bibliography 65 3 Abstract S. Allan, 2007. Commando Country. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Publishing. Commando Country assesses the nature of more than 30 special training centres that operated in the Scottish highlands between 1940 and 1945, in order to explore the origins, evolution and culture of British special service training during the Second World War. -

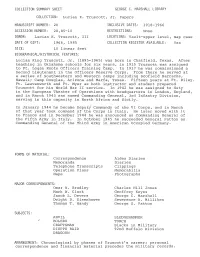

Inclusive Dates: 1918-1966 Restrictions: Collection

COLLECTION SUMMARY SHEET GEORGE C. MARSHALL LIBRARY COLLECTION: Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. Papers MANUSCRIPT NUMBER: 20 INCLUSIVE DATES: 1918-1966 ACCESSION NUMBER: 20,85-10 RESTRICTIONS: None DONOR: Lucian K. Truscott, III LOCATIONS: Vault-upper level, map case DATE OF GIFT: 1966, 1985 COLLECTION REGISTER AVAILABLE: Yes SIZE: 10 linear feet BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL FEATURES: Lucian King Truscott, Jr. (1895-1965) was born in Chatfield, Texas. After teaching in Oklahoma schools for six years, in 1915 Truscott was assigned to Ft. Logan Roots Officers Training Camp. In 1917 he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Officers Reserve Corps. From there he served at a series of Southwestern and Western camps including Scofield Barracks, Hawaii; Camp Douglas, Arizona and Marfa, Texas. Fifteen years at Ft. Riley. Ft. Leavenworth and Ft. Myer as both iI1;structor and student prepared Truscott for his World War II service. In 1942 he was assigned to duty in the European Theater of Operations with headquarters in London, England, and in March 1943 was named Commanding General, 3rd Infantry Division, serving in this capacity in North Africa and Sicily. " I In January 1944 he became Deputy Commandy of the VI Corps, and in March of that year took command of the Corps in Italy. He later moved with it to France and in December 1944 he was announced as Commanding General of the Fifth Army in Italy. In October 1945 he succeeded General Patton as Commanding General of the Third Army in American Occupied Germany. FORMS OF MATERIAL: Correspondence Aides Diaries Memoranda Diaries Telephone Transcripts Clippings Operation Plans Memorabilia lvlaps Photographs MAJOR CORRESPONDENTS: Omar N. -

Download Catalogue 31

WORLD WAR BOOKS Oaklands, Camden Park, Tunbridge Wells, Kent, England. TN2 5AE Tel / Fax 01892 538465 Email [email protected] TERMS OF BUSINESS The items in this catalogue are in net sterling prices. Postage and insurance are additional. If overseas customers wish to use airmail then please advise. The goods remain the property of World War Books until full payment has been received. PAYMENT Post and packing will be quoted at the time of order. For new or overseas customers payment will be required prior to despatch of books. For existing customers invoices are payable on receipt of books. Payment from abroad should be by sterling cheque drawn on UK bank, sterling bankers draft, or payment direct into our bank account using BIC. We are also pleased to take VISA or MASTERCARD in payment. WANTS LIST We make every effort to help customers find the book they require and are happy to add wants lists to our files. PURCHASE OF BOOKS AND EPHEMERA We are very keen to purchase good quality books and particularly ephemera including photo albums, scrapbooks, manuscripts, trench maps. We are always interested in any quantity, single items or collections and will travel anywhere to view and collect, if necessary. WORLD WAR BOOKS Catalogue 31 CONTENTS Items DIARIES, BOUND REPORTS, PHOTOGRAPH ALBUM, 1 - 43 EPHEMERA TRENCH MAPS 44 - 49 WORLD WAR ONE, INCLUDING REGIMENTAL 50 - 100 HISTORIES BOOKS FROM THE LIBRARY OF THE LATE ADMIRAL 101 - 152 & LADY KEYES & LORD ROGER KEYES WORLD WAR TWO (INCLUDING REGIMENTAL 153 - 166 HISTORIES ETC.) MANUALS (ARTILLERY, MACHINE GUN, MORTARS, 167 - 183 AMMUNITION MANUALS ETC. -

Bombing the European Axis Powers a Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945

Inside frontcover 6/1/06 11:19 AM Page 1 Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 Air University Press Team Chief Editor Carole Arbush Copy Editor Sherry C. Terrell Cover Art and Book Design Daniel M. Armstrong Composition and Prepress Production Mary P. Ferguson Quality Review Mary J. Moore Print Preparation Joan Hickey Distribution Diane Clark NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page i Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 RICHARD G. DAVIS Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2006 NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page ii Air University Library Cataloging Data Davis, Richard G. Bombing the European Axis powers : a historical digest of the combined bomber offensive, 1939-1945 / Richard G. Davis. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-148-1 1. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations. 2. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations––Statistics. 3. United States. Army Air Forces––History––World War, 1939- 1945. 4. Great Britain. Royal Air Force––History––World War, 1939-1945. 5. Bombing, Aerial––Europe––History. I. Title. 940.544––dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Book and CD-ROM cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page iii Contents Page DISCLAIMER . -

Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES CSC 31 / CCEM 31 MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES COORDINATION AND COMMAND RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN AXIS POWERS IN THE NAVAL WAR IN THE MEDITERRANEAN 1940-1943 By /par KKpt/LCdr/Capc Andreas Krug This paper was written by a student attending La présente étude a été rédigée par un stagiaire the Canadian Forces College in fulfilment of one du Collège des Forces canadiennes pour of the requirements of the Course of Studies. satisfaire à l'une des exigences du cours. The paper is a scholastic document, and thus L'étude est un document qui se rapporte au contains facts and opinions which the author cours et contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and correct for que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et the subject. -

Raising a Pragmatic Army Officer Education at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1946

RAISING A PRAGMATIC ARMY OFFICER EDUCATION AT THE U.S. ARMY COMMAND AND GENERAL STAFF COLLEGE, 1946 - 1986 BY C2010 Michael David Stewart Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Theodore A. Wilson Chairperson Adrian R. Lewis Jeffrey Moran James H. Willbanks Susan B. Twombly Date Defended 4/22/2010 The Dissertation Committee for Michael David Stewart certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: RAISING A PRAGMATIC ARMY OFFICER EDUCATION AT THE U.S. ARMY COMMAND AND GENERAL STAFF COLLEGE, 1946 - 1986 Committee: Theodore A. Wilson Chairperson Adrian R. Lewis Jeffrey Moran James H. Willbanks Susan B. Twombly Date approved: 4/22/2010 i ABSTRACT RAISING A PRAGMATIC ARMY: Officer Education at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1946 – 1986 By Michael D. Stewart Department of History, University of Kansas Professor Theodore A. Wilson, Advisor This dissertation explains the evolution of the United States Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas from 1946 to 1986. Examination of change at the United States Army’s Command and General Staff College focuses on the curriculum as a system—students, instructors, professional knowledge, and lessons—mixing within a framework to produce an educational outcome of varying quality. Consideration of non- resident courses and allied officer attendance marks two unique aspects of this study. The curriculum of the Command and General Staff College changed drastically over four decades because of the rapid expansion of professional jurisdiction, an inability to define the Army’s unique body of professional knowledge, and shifting social and professional characteristics of the U.S. -

Bombing the European Axis Powers a Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945

Inside frontcover 6/1/06 11:19 AM Page 1 Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 Air University Press Team Chief Editor Carole Arbush Copy Editor Sherry C. Terrell Cover Art and Book Design Daniel M. Armstrong Composition and Prepress Production Mary P. Ferguson Quality Review Mary J. Moore Print Preparation Joan Hickey Distribution Diane Clark NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page i Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 RICHARD G. DAVIS Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2006 NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page ii Air University Library Cataloging Data Davis, Richard G. Bombing the European Axis powers : a historical digest of the combined bomber offensive, 1939-1945 / Richard G. Davis. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-148-1 1. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations. 2. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations––Statistics. 3. United States. Army Air Forces––History––World War, 1939- 1945. 4. Great Britain. Royal Air Force––History––World War, 1939-1945. 5. Bombing, Aerial––Europe––History. I. Title. 940.544––dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Book and CD-ROM cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page iii Contents Page DISCLAIMER . -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Commando Country Special training centres in the Scottish highlands, 1940-45. Stuart Allan PhD (by Research Publications) The University of Edinburgh 2011 This review and the associated published work submitted (S. Allan, 2007. Commando Country. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Publishing) have been composed by me, are my own work, and have not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Stuart Allan 11 April 2011 2 CONTENTS Abstract 4 Critical review Background to the research 5 Historiography 9 Research strategy and fieldwork 25 Sources and interpretation 31 The Scottish perspective 42 Impact 52 Bibliography 56 Appendix: Commando Country bibliography 65 3 Abstract S. Allan, 2007. Commando Country. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Publishing. Commando Country assesses the nature of more than 30 special training centres that operated in the Scottish highlands between 1940 and 1945, in order to explore the origins, evolution and culture of British special service training during the Second World War. -

Download (1MB)

In the Picture COSTERUS NEW SERIES 207 Series Editors: C.C. Barfoot, Laszlo Sandor Chardonnens and Theo D'haen In the Picture The Facts behind the Fiction in Evelyn Sword of Honour Waugh's . Donat Gallagher and Carlos Villar Flor ~ Amsterdam-New York, NY 2014 Quotations from the works of Evelyn Waugh © Evelyn Waugh © The Estate of Laura Waugh Used by permission. All rights reserved. All other rights in the Author's works, including but not limited to all further publication, serial, syndication and translation rights, whether now existing or which may hereafter come into existence which are not specifically granted to the Licensee in this letter are reserved to the Proprietor. No further use of this material in extended distribution, other media, further printings or future editions shall be made without the express written consent of The Wylie Agency (UK) Ltd. Cover artist: Axel Cardona. Cover design: Aart Jan Bergshoeff The paper on which this book is printed meets the requirements of "ISO 9706:1994, Information and documentation - Paper for documents - Requirements for permanence". ISBN: 978-90-420-3900-1 E-Book ISBN: 978-94-012-1182-6 ©Editions Rodopi B.V., Amsterdam - New York, NY 2014 Printed in the Netherlands CONTENTS Acknowledgments Vll Introduction PART I: A PLACE IN THAT BATTLE 15 Carlos Villar Flor Chapter 1 The Enemy Was Plain in View 17 Chapter 2 The Commandos and the Battle for Crete (1940-41) 49 Chapter 3 The Locust Years 1941-45 91 PART II: FOUR MYTHS EXPLORED 133 Donat Gallagher Chapter 4 Was Waugh ''Utterly Unfitted to Be an Officer"? 135 Chapter 5 Cretan Labyrinth: The Way Out 173 Chapter 6 Liquidated! How Lord Lovat "Kicked Waugh Out" of the Special Service Brigade and Fantasized about It Afterwards 219 Chapter 7 Civil Waugh in Yugoslavia 253 CONCLUSIONS 303 Bibliography 331 Index 347 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are sincerely grateful to many persons and institutions for their assistance and encouragement. -

Long Range Desert Group (LRDG ) Covers the Minefields: Areas with Operations of the British LRDG and Special Mines Or Axis Defenses

COMMANDO mini GAME SCENARIO RULES 32.0 RESERVE RECRUIT counter) adjacent to a space containing a face combat. An Air Supply marker may be used POINTS (RP) down Objective marker. Roll one die: if even, reveal the objective; if odd, nothing happens. in the same way to Increase movement or RP which you did not expend during initial For an Air Recon, use one Airstrike and reveal firepower. After the conclusion of the movement deployment can be saved to: 1) Purchase one face down Objective anywhere on the or combat in which the supply column or Air additional Ops: pay 2 RP and receive one map on an even roll; if odd, nothing happens. Supply is so employed, roll one die: on an even additional Op. This can be done at any In either case, check for availability (29.0). result, the supply column or Air Supply remains point in a scenario. Or 2) . In a campaign in play. On an odd result a supply column or game, RPs can be accrued from one 34.0 additional logisticS Air Supply is placed in the Recruit Pool. mission to the next (but see 39.13). A player may use a supply column to increase the movement factor of a force with which 35.0 AIRCRAFT TURNAROUND 33.0 RECONNAISSANCE it moves by one space. Additionally, a player Airstrikes and Air Supply returned to the A force conducting an Operation can attempt may use a supply column to declare “Full Recruit Pool due to an Availability check one Recon. This is done at the start of the Firepower” at the beginning of a battle if it (29.0) may be returned to play by paying one Op, prior to movement, and can be either one is part of a force engaged in combat.