This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

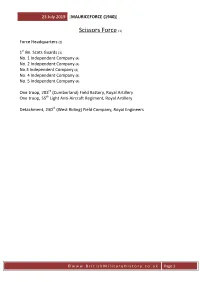

Scissors Force (1940)

23 July 2019 [MAURICEFORCE (1940)] Scissors Force (1) Force Headquarters (2) st 1 Bn. Scots Guards (3) No. 1 Independent Company (4) No. 2 Independent Company (4) No.3 Independent Company (4) No. 4 Independent Company (4) No. 5 Independent Company (4) One troop, 203rd (Cumberland) Field Battery, Royal Artillery One troop, 55th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery Detachment, 230th (West Riding) Field Company, Royal Engineers ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Page 1 23 July 2019 [MAURICEFORCE (1940)] NOTES: 1. Scissors Force was formed in early May 1940 under the command of Colonel Colin McVean GUBBINS. The role of this force was to form a base in the Bodo, Mo and Mosjoen area to the south of Narvik and to block and delay the German advance from the south. 2. The Force Headquarters was formed from the staff of the 61st Infantry Division on 15 April 1940. 3. The 1st Bn. Scots Guards was part of the 24th Infantry Brigade (Guards) which was sent to assist in blocking the road at Mo. 4. These companies were formed with volunteers from the Territorial Army divisions then stationed in the United Kingdom. They were: Ø No. 1 Independent Company – Formed by the 52nd (Lowland) Division; Ø No. 2 Independent Company – Formed by the 53rd (Welsh) Division; Ø No. 3 Independent Company – Formed by the 54th (East Anglian) Division; Ø No. 4 Independent Company – Formed by the 55th (West Lancashire) Division; Ø No. 5 Independent Company – Formed by the 56th (London) Division; Each company comprised five officers and about two-hundred and seventy men organised into three platoons, each consisting of three sections. -

Loch Arkaig Land Management Plan Summary

Loch Arkaig Land Management Plan Summary Loch Arkaig Forest flanks the Northern and Southern shores of Loch Arkaig near the hamlets of Clunes and Achnacarry, 15km North of Fort William. The Northern forest blocks are accessed by a minor dead end public road. The Southern blocks are accessed by boat. This area is noted for the fishing, but more so for its link with the training of commandos for World War II missions. The Allt Mhuic area of the forest is well known for its invertebrates such as the Chequered Skipper butterfly. Loch Arkaig LMP was approved on 19/10/2010 and runs for 10 years. What’s important in the new plan: Gradual restoration of native woodland through the continuation of a phased clearfell system Maximisation of available commercial restocking area outwith the PAWS through keeping the upper margin at the altitude it is at present and designing restock coupes to sit comfortably within the landscape Increase butterfly habitat through a network of open space and expansion of native woodland. Enter into discussions with Achnacarry Estate with the aim of creating a strategic timber transport network which is mutually beneficial to the FC and the Estate, with the aim of facilitating the harvesting of timber and native woodland restoration from the Glen Mallie and South Arkaig blocks. The primary objectives for the plan area are: Production of 153,274m3 of timber Restoration of 379 ha of native woodland following the felling of non- native conifer species on PAWS areas To develop access to the commercial crops to enable harvesting operations on the South side of Loch Arkaig To restock 161 ha of commercial productive woodland. -

Appeal Citation List External

The Highland and Western Isles Valuation Joint Board Citation List Valuation Appeal Committee Hearing Date of Hearing : 08 March 2018 Citations Issued : 24 November 2017 Seq Appeal Reference Description & Situation No Number 1 265435 01/05/394028/8 Site for ATM , 55 High Street, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4NE 2 268844 03/02/002650/4 Hydro Elec Works , Loch Rosque Hydro Scheme, Achnasheen, Ross-shire, IV22 2ER 3 268842 03/03/083400/9 Hydro Elec Works , Allt an Ruigh Mhoir Hydro, Heights of Kinlochewe, Kinlochewe, Achnasheen, Ross-shire, IV22 2 PA 4 268839 03/03/083600/7 Hydro Elec Works , Abhainn Srath Chrombaill Upper Hydro, Heights of Kinlochewe, Kinlochewe, Achnasheen, Ross-shire, IV22 2 PA 5 262235 03/09/300105/1 Depot (Miscellaneous), Ferry Road, Dingwall, Ross-shire, IV15 9QS 6 262460 04/06/031743/0 Workshop (Commercial), 3A Broom Place, Portree, Isle of Skye, IV51 9HL 7 268835 05/03/001900/4 Hydro Elec Works , Hydro Electric Works, Outward Bound Locheil Centre, Achdalieu, Fort William, PH33 7NN 8 268828 05/03/081950/3 Hydro Elec Works , Hydro Electric Works, Moy Hydro, Moy Farm, Banavie, Fort William, Inverness-shire, PH33 7PD 9 260730 05/03/087560/2 Hydro Elec Works , Rubha Cheanna Mhuir, Achnacarry, Spean Bridge, Inverness-shire, PH34 4EL 10 260728 05/03/087570/5 Hydro Elec Works , Achnasaul, Achnacarry, Spean Bridge, Inverness-shire, PH34 4EL 11 260726 05/03/087580/8 Hydro Elec Works , Arcabhi, Achnacarry, Spean Bridge, Inverness-shire, PH34 4EL 12 257557 05/06/023250/7 Hydro Elec Works , Hydro Scheme, Allt Eirichaellach, Glenquoich, -

Does Red Clydeside Really Matter Anymore?

Christopher Fevre 100009227 ‘Does Red Clydeside Really Matter Any More?’ Word Count: 4,290 Red Clydeside, described aptly by Maggie Craig as ‘those heady decades at the beginning of the twentieth century when passionate people and passionate politics swept like a whirlwind through Glasgow’ is arguably the most significant yet controversial subject in Scottish labour and social history.1 Yet, it is because of this controversy that questions still linger regarding the significance of Red Clydeside in the overall narrative of British and more specifically, Scottish history. The title of this paper, ‘Does Red Clydeside Really Matter Any More?’ has been generously borrowed from Terry Brotherstone’s interesting article in Militant Workers: Labour and Class Conflict on the Clyde 1900- 1950.2 Following a decade in which the legacy of the Red Clydesiders had been systematically attacked by revisionist historians agitated by contemporary attempts to link the events on the Clyde with those occurring in Russia in 1917, Brotherstone emphasised the new and developing common sense approach to the Red Clydeside debate. It was argued that ‘A new consensus seems to be emerging... which acknowledges the significance of the events associated with Red Clydeside, but seeks to dissociate them from what is now perceived as the ‘myth’ or ‘legend’ that they involved a revolutionary challenge to the British state’. However, as a consequence of the ever changing nature of Red Clydeside historiography it is now time for a re-assessment of the significance of Red Clydeside which incorporates new research into the rise of left-wing politics in Scotland more generally. -

Introduction the Waldegrave Initiative Is the Name Given to a Policy Introduced in 1992 by Lord Waldegrave, an English Conservat

Introduction The Waldegrave Initiative is the name given to a policy introduced in 1992 by Lord Waldegrave, an English Conservative politician who served in the British Cabinet from 1990 – 1997. Under this policy, all government departments were encouraged to re-examine what had been previously regarded as particularly sensitive records, with the objective of declassifying a greater quantity of information. This initiative is widely regarded as the precursor to the UK’s Freedom of Information Act 2000, and it set a precedent of declassification across Western democracies. The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a secret British organisation formed 22 July 1940 by Winston Churchill to conduct espionage, sabotage, and reconnaissance in occupied Europe against the Axis powers as well as to aid local resistance movements. As Mark Seaman put it, the SOE was formed to “foster occupied Europe’s resistance groups” and ensure that “Nazi occupation wasn’t an easy thing”.1 It operated in all countries or former countries occupied by or attacked by the Axis forces, except where demarcation lines were agreed with Britain's principal allies – namely the Soviet Union and the United States of America. Initially it was also involved in the formation of the Auxiliary Units, a top secret "stay-behind" resistance organisation, which would have been activated in the event of a German invasion of mainland Britain.2 To those who were part of the SOE or liaised with it, it was sometimes referred to as "the Baker Street Irregulars" (after the location of its London headquarters). It was also known as "Churchill's Secret Army" or the "Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare". -

0714685003.Pdf

CONTENTS Foreword xi Acknowledgements xiv Acronyms xviii Introduction 1 1 A terrorist attack in Italy 3 2 A scandal shocks Western Europe 15 3 The silence of NATO, CIA and MI6 25 4 The secret war in Great Britain 38 5 The secret war in the United States 51 6 The secret war in Italy 63 7 The secret war in France 84 8 The secret war in Spain 103 9 The secret war in Portugal 114 10 The secret war in Belgium 125 11 The secret war in the Netherlands 148 12 The secret war in Luxemburg 165 ix 13 The secret war in Denmark 168 14 The secret war in Norway 176 15 The secret war in Germany 189 16 The secret war in Greece 212 17 The secret war in Turkey 224 Conclusion 245 Chronology 250 Notes 259 Select bibliography 301 Index 303 x FOREWORD At the height of the Cold War there was effectively a front line in Europe. Winston Churchill once called it the Iron Curtain and said it ran from Szczecin on the Baltic Sea to Trieste on the Adriatic Sea. Both sides deployed military power along this line in the expectation of a major combat. The Western European powers created the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) precisely to fight that expected war but the strength they could marshal remained limited. The Soviet Union, and after the mid-1950s the Soviet Bloc, consistently had greater numbers of troops, tanks, planes, guns, and other equipment. This is not the place to pull apart analyses of the military balance, to dissect issues of quantitative versus qualitative, or rigid versus flexible tactics. -

Suez 1956 24 Planning the Intervention 26 During the Intervention 35 After the Intervention 43 Musketeer Learning 55

Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd i 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East Louise Kettle 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiiiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Louise Kettle, 2018 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/1 3 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 3795 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3797 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3798 1 (epub) The right of Louise Kettle to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iivv 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Contents Acknowledgements vii 1. Learning from History 1 Learning from History in Whitehall 3 Politicians Learning from History 8 Learning from the History of Military Interventions 9 How Do We Learn? 13 What is Learning from History? 15 Who Learns from History? 16 The Learning Process 18 Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 21 2. -

Ethnicity and the Writing of Medieval Scottish History1

The Scottish Historical Review, Volume LXXXV, 1: No. 219: April 2006, 1–27 MATTHEW H. HAMMOND Ethnicity and the Writing of Medieval Scottish history1 ABSTRACT Historians have long tended to define medieval Scottish society in terms of interactions between ethnic groups. This approach was developed over the course of the long nineteenth century, a formative period for the study of medieval Scotland. At that time, many scholars based their analysis upon scientific principles, long since debunked, which held that medieval ‘peoples’ could only be understood in terms of ‘full ethnic packages’. This approach was combined with a positivist historical narrative that defined Germanic Anglo-Saxons and Normans as the harbingers of advances in Civilisation. While the prejudices of that era have largely faded away, the modern discipline still relies all too often on a dualistic ethnic framework. This is particularly evident in a structure of periodisation that draws a clear line between the ‘Celtic’ eleventh century and the ‘Norman’ twelfth. Furthermore, dualistic oppositions based on ethnicity continue, particu- larly in discussions of law, kingship, lordship and religion. Geoffrey Barrow’s Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland, first published in 1965 and now available in the fourth edition, is proba- bly the most widely read book ever written by a professional historian on the Middle Ages in Scotland.2 In seeking to introduce the thirteenth century to such a broad audience, Barrow depicted Alexander III’s Scot- land as fundamentally -

To Revel in God's Sunshine

To Revel in God’s Sunshine The Story of RSM J C Lord MVO MBE Compiled by Richard Alford and Colleagues of RSM J C Lord © R ALFORD 1981 First Edition Published in 1981 Second Edition Published Electronically in 2013 Cover Pictures Front - Regimental Sergeant Major J C Lord in front of the Grand Entrance to the Old Building, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. Rear - Army Core Values To Revel in God’s Sunshine The Story of the Army Career of the late Academy Sergeant Major J.C. Lord MVO MBE As related by former Recruits, Cadets, Comrades and Friends Compiled by Richard Alford (2nd Edition - Edited by Maj P.E. Fensome R IRISH and Lt Col (Retd) A.M.F. Jelf) John Lord firmly believed the words of Emerson: “Trust men and they will be true to you. Treat them greatly and they will show themselves great.” Dedicated to SOLDIERS SOLDIERS WHO TRAIN SOLDIERS SOLDIERS WHO LEAD SOLDIERS The circumstances of many contributors to this book will have changed during the course of research and publication, and apologies are extended for any out of date information given in relation to rank and appointment. i John Lord when Regimental Sergeant Major The Parachute Regiment Infantry Training Centre ii CONTENTS 2ND EDITION Introduction General Sir Peter Wall KCB CBE ADC Gen – CGS v Foreword WO1 A.J. Stokes COLDM GDS – AcSM R M A Sandhurst vi Editor’s Note Major P.E Fensome R IRISH vii To Revel in God’s Sunshine Introduction The Royal British Legion Annual Parade at R.M.A Sandhurst viii Chapter 1 The Grenadier Guards, Brighton Police Force 1 Chapter 2 Royal Military College, Sandhurst. -

The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-39

THE POLICY OF NEGLECT: THE CANADIAN MILITIA IN THE INTERWAR YEARS, 1919-39 ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________ by Britton Wade MacDonald January, 2009 iii © Copyright 2008 by Britton W. MacDonald iv ABSTRACT The Policy of Neglect: The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-1939 Britton W. MacDonald Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Dr. Gregory J. W. Urwin The Canadian Militia, since its beginning, has been underfunded and under-supported by the government, no matter which political party was in power. This trend continued throughout the interwar years of 1919 to 1939. During these years, the Militia’s members had to improvise a great deal of the time in their efforts to attain military effectiveness. This included much of their training, which they often funded with their own pay. They created their own training apparatuses, such as mock tanks, so that their preparations had a hint of realism. Officers designed interesting and unique exercises to challenge their personnel. All these actions helped create esprit de corps in the Militia, particularly the half composed of citizen soldiers, the Non- Permanent Active Militia. The regulars, the Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force), also relied on their own efforts to improve themselves as soldiers. They found intellectual nourishment in an excellent service journal, the Canadian Defence Quarterly, and British schools. The Militia learned to endure in these years because of all the trials its members faced. The interwar years are important for their impact on how the Canadian Army (as it was known after 1940) would fight the Second World War. -

Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-8-2020 "The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812 Joseph R. Miller University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Joseph R., ""The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3208. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3208 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE MEN WERE SICK OF THE PLACE”: SOLDIER ILLNESS AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE WAR OF 1812 By Joseph R. Miller B.A. North Georgia University, 2003 M.A. University of Maine, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2020 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Liam Riordan, Professor of History Kathryn Shively, Associate Professor of History, Virginia Commonwealth University James Campbell, Professor of Joint, Air War College, Brigadier General (ret) Michael Robbins, Associate Research Professor of Psychology Copyright 2020 Joseph R. -

Dutch Military Landscapes Heritage and Archaeology on WWII Conflict Sites

Dutch Military Landscapes Heritage and Archaeology on WWII conflict sites Max VAN DER SCHRIEK Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Abstract: In the Netherlands, archaeological research concerning World War II (WWII) is not very well explored compared with the neighboring countries. Its key methodologies were developed already in the 1980s in the United States, where both specialized field techniques (such as advanced metal detectors) and methods for analysis like Geographical Information Systems (GIS) were administered to locate specific artefacts and to map and reconstruct military strategies and other war events. Dutch (conflict) archaeologists still need to develop, practice and reflect international developments in the subject area to learn from the experiences of colleagues abroad. Individual archaeologists participated in the research out of personal interest and/or a particular personal commitment to the features and artefacts they came across during excavations. However, there are still large differences in the approach to the archaeology of WWII between the various commercial excavation companies, provincial administration and municipalities. Even when recording has been systematically undertaken, there have sometimes been administrative, conservation, and legal difficulties in dealing with WWII conflict sites in the Netherlands. Modern Conflict Archaeology plays a vital role with regard to the preservation of these sites and relics. There are several non-invasive approaches and techniques which we can use without any juridical problems, for example KOCOA (Key terrain, Obstacles, Cover and concealment, Observation and fields of fire, Avenues of approach), an established approach to military analysis, and the application of LiDAR (Li ght Detection And Ranging), a remote sensing technology which can provide a detailed digital elevation model of a landscape.