Raising a Pragmatic Army Officer Education at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1946

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

68 STAT. Private Law 391 CHAPTER 260 Be It Enacted Hy the /Senate

A62 PRIVATE LAW 391-JUNE 3, 1954 [68 STAT. Private Law 391 CHAPTER 260 June 3, 19S4 ^^ ACT —CH' R. 4996]— p^j^. ^jjg i-eiigf of Colonel Henry M. Denning, and others. Be it enacted hy the /Senate and House of Representatives of the Col. Henry M. Denning and United States of America in Congress assembled, Tliat relief is hereby others. " granted the various disbursing officers of the United States or claim ants hereinafter mentioned in amounts shown herein, said amounts representing amounts of erroneous payments made by said disbursing officers of public funds for which said officers are accountable or amounts due said claimants as listed in and under the circumstances described in identical letters of the Secretary of the Army to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and chairman, Committee on Armed Services, United States Senate. SEC. 2. That the Comptroller General of the United States be, and he is hereby, authorized and directed to credit in the accounts of the following officers and employees of the Army of the United States the amounts set opposite their names: Colonel Henry M. Denning, Finance Corps (now retired), $133.77; Colonel C. K. McAlister, Finance Corps, $39.79; Colonel Frank Richards, Finance Corps (now retired), $34.69; Colonel H. R. Cole, Corps of Engineers, $18.72, the said amounts representing erroneous payments of public funds for which these persons are accountable, resulting from minor errors in deter mining amounts of pay and allowances due former members of the Civilian Conservation Corps, former officers, enlisted men, and civilian employees of the Army or contractors from whom collection of the overpayments cannot be effected, and which amounts have been disal lowed by the Comptroller General of the United States. -

THE ARIZONA ROUGH RIDERS by Harlan C. Herner a Thesis

The Arizona rough riders Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Herner, Charles Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 02:07:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551769 THE ARIZONA ROUGH RIDERS b y Harlan C. Herner A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1965 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of require ments for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under the rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of this material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: MsA* J'73^, APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: G > Harwood P. -

Profile of the United States Army (2016)

Interested in becoming a member of AUSA? Join online at: www.ausa.org/membership Profile of the United States Army is produced for you, and we value your opinion about its appearance and content. Please send any feedback (positive or negative) regarding this edition of Profile to Ellen Toner at: [email protected] Developed by AUSA’s Institute of Land Warfare RESEARCH AND WRITING EDITING Ellen Toner Sandra J. Daugherty GRAPHICS AND DESIGN TECHNICAL SUPPORT Kevin Irwin Master Print, Inc. Photographs courtesy of the United States Army and the Department of Defense. ©2016 by the Association of the United States Army. All rights reserved. Association of the United States Army Institute of Land Warfare 2425 Wilson Boulevard, Arlington, Virginia 22201-3385 703-841-4300 • www.ausa.org CONTENTS F FOREWORD v 1 NATIONAL DEFENSE 1 2 LAND COMPONENT 9 3 ARMY ORGANIZATION 21 4 THE SOLDIER 31 5 THE UNIFORM 39 6 THE ARMY ON POINT 49 7 ARMY FAMILIES 55 8 ARMY COMMAND STRUCTURE 63 9 ARMY INSTALLATIONS 85 G GLOSSARY 93 M MAPS 95 III FOREWORD hroughout its 241 years, the United States has maintained its Army as the world’s most Tformidable fighting force. Under General George Washington, the Continental Army fought for the independence and rights of a fledgling nation. This first American Army— primarily made up of ordinary citizens with little or no warfighting experience—comprised Soldiers who held a zealous desire for independence. Their motivation for freedom ultimately led them to defeat the well-established and well-trained British army. This motivation and love for country are instilled in today’s Soldiers as they continue to fight for and defend freedom from oppression for all. -

Page 2033 TITLE 10—ARMED FORCES § 3064 (D) the Organized

Page 2033 TITLE 10—ARMED FORCES § 3064 (d) The organized peace establishment of the (13) such other basic branches as the Sec- Army consists of all— retary considers necessary. (1) military organizations of the Army with (b) The Secretary may discontinue or consoli- their installations and supporting and auxil- date basic branches of the Army for the duration iary elements, including combat, training, ad- of any war, or of any national emergency de- ministrative, and logistic elements; and clared by Congress. (2) members of the Army, including those (c) The Secretary may not assign to a basic not assigned to units; branch any commissioned officer appointed in a necessary to form the basis for a complete and special branch. immediate mobilization for the national defense (Aug. 10, 1956, ch. 1041, 70A Stat. 166.) in the event of a national emergency. (Aug. 10, 1956, ch. 1041, 70A Stat. 166; Pub. L. HISTORICAL AND REVISION NOTES 109–163, div. A, title X, § 1057(a)(6), Jan. 6, 2006, Revised 119 Stat. 3441.) section Source (U.S. Code) Source (Statutes at Large) HISTORICAL AND REVISION NOTES 3063(a) ..... 10:1g(a) (less words of 1st June 28, 1950, ch. 383, sentence after semi- § 306(a), 64 Stat. 269. colon, and less last Revised Source (U.S. Code) Source (Statutes at Large) sentence). section 3063(b) ..... 10:1g(a) (last sentence). 3063(c) ..... 10:1g(a) (words of 1st sen- 3062(a) ..... 10:20. July 10, 1950, ch. 454, § 2, tence after semicolon). 3062(b) ..... 5:181–1(e). § 101, 64 Stat. 321. 3062(c) .... -

The Mexican General Officer Corps in the US

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Latin American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-1-2011 Valor Wrought Asunder: The exM ican General Officer Corps in the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847. Javier Ernesto Sanchez Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ltam_etds Recommended Citation Sanchez, Javier Ernesto. "Valor Wrought Asunder: The exM ican General Officer Corps in the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847.." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ltam_etds/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Latin American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Javier E. Sánchez Candidate Latin-American Studies Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: L.M. García y Griego, Chairperson Teresa Córdova Barbara Reyes i VALOR WROUGHT ASUNDER: THE MEXICAN GENERAL OFFICER CORPS IN THE U.S.-MEXICAN WAR, 1846 -1847 by JAVIER E. SANCHEZ B.B.A., BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO 2009 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2011 ii VALOR WROUGHT ASUNDER: THE MEXICAN GENERAL OFFICER CORPS IN THE U.S.-MEXICAN WAR, 1846-1847 By Javier E. Sánchez B.A., Business Administration, University of New Mexico, 2008 ABSTRACT This thesis presents a reappraisal of the performance of the Mexican general officer corps during the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847. -

Basic Branches of the United States Army Basic Branch Information After

Basic Branches of the United States Army Basic Branch Information After graduation from ROTC Advanced Camp and before commissioning, cadets make the most important decision of their emerging Army career which branch to serve in. The reasons for choosing a branch are varied and personal. The choice can based on the desire to use the academic credentials gained while at school or simply a desire to do something exciting. The 16 basic branches available to cadets are all important to the total Army force and each cannot function without the other. Adjutant General To plan, develop, and direct systems for managing the Army's personnel, administrative, and Army band systems. These systems impact on unit readiness, morale, and soldier career satisfaction, and cover the life cycle management of all Army personnel. Air Defense Artillery The primary mission will be to protect the force and critical tactical and geopolitical assets. This important task is made especially challenging by the evolution of modern tactical ballistic missiles, unmanned aerial vehicles and aircraft. Armor/Cavalry The heritage and spirit of the United States Calvary lives today in Armor. And although the horse has been replaced by 60 tons of steel driven by 1,500HP engine, the dash and daring of the Horse Calvary still reside in Armor. Today, the Armor branch of the Army (which includes Armored Calvary), is one of the Army's most versatile combat arms. It’s continually evolving to meet worldwide challenges and potential threats. Aviation One of the most exciting and capable elements of the Combined Arms Team. As the only branch of the Army that operates in the third dimension of the battlefield, Aviation plays a key role by performing a wide range of missions under diverse conditions. -

Michael Schroeder Retired at US Army [email protected]

Michael Schroeder Retired at US Army [email protected] Summary • Talented professional seeking meaningful and responsible opportunities to apply my knowledge, skills, experience and expertise in service to society. • Accomplished leader with over three decades of leadership and staff experience in progressively larger and more complex organizations with a blend of operational and financial management experience and expertise. • Established an exemplary track record as a principal financial advisor to senior executive leaders with fiduciary oversight responsibilities for multi-billion dollar programs for operations, equipment, procurement and technology. • Proven leader of multi-functional, formal/informal teams focused on complex problem-solving and the operational synchronization of large, integrated organizations. • Strong business acumen, highest integrity, excellent communicator…well-spoken, good writer. • Active Federal Top Secret – Sensitive Compartmented Information (SCI) Security Clearance. AREAS OF EXPERTISE: Leadership; Strategic Planning & Implementation; Accounting/Funds Control; Financial Management; Employee Relations; Auditing/Internal Controls; Budget Planning & Execution; Process Improvement; Procurement/Acquisition; Personnel Management; Training & Development; Change Management; Program Management; Performance Management; Operations Experience Retired at US Army February 2017 - Present CFO January 2016 - February 2017 (1 year 2 months) Budget Officer, Supervisor at United States Army Forces Command (FORSCOM) -

10, George C. Marshall

'The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, Department of Defense or the US Government.'" USAFA Harmon Memorial Lecture #10 “George C. Marshall: Global Commander” Forrest C. Pogue, 1968 It is a privilege to be invited to give the tenth lecture in a series which has become widely-known among teachers and students of military history. I am, of course, delighted to talk with you about Gen. George C. Marshall with whose career I have spent most of my waking hours since1956. Douglas Freeman, biographer of two great Americans, liked to say that he had spent twenty years in the company of Gen. Lee. After devoting nearly twelve years to collecting the papers of General Marshall and to interviewing him and more than 300 of his contemporaries, I can fully appreciate his point. In fact, my wife complains that nearly any subject from food to favorite books reminds me of a story about General Marshall. If someone serves seafood, I am likely to recall that General Marshall was allergic to shrimp. When I saw here in the audience Jim Cate, professor at the University of Chicago and one of the authors of the official history of the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, I recalled his fondness for the works of G.A. Henty and at once there came back to me that Marshall once said that his main knowledge of Hannibal came from Henty's The Young Carthaginian. If someone asks about the General and Winston Churchill, I am likely to say, "Did you know that they first met in London in 1919 when Marshall served as Churchill's aide one afternoon when the latter reviewed an American regiment in Hyde Park?" Thus, when I mentioned to a friend that I was coming to the Air Force Academy to speak about Marshall, he asked if there was much to say about the General's connection with the Air Force. -

The National Guard Bureau

NATIONAL GUIDELINES FOR APPRENTICESHIP STANDARDS DEVELOPED BY THE NATIONAL GUARD BUREAU FOR ALL MILITARY OCCUPATIONS, SPECIALTIES, AND BRANCHES LISTED IN THESE STANDARDS DEVELOPED IN COOPERATION WITH THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR OFFICE OF APPRENTICESHIP APPROVED AND CERTIFIED BY THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR, OFFICE OF APPRENTICESHIP BY: __/s/___________________ JOHN V. LADD, ADMINISTRATOR OFFICE OF APPRENTICESHIP CERTIFICATION DATE: ____December 10, 2010____ CERTIFICATION NUMBER: ____C-2011-02_________ NOTICE: National Guard Apprentices are required to read these Standards before beginning their apprenticeship program. FOREWORD The National Guard Bureau recognizes the need for structured training programs to maintain the high level of skill and competence demanded in industry. Registered apprenticeship is the most practical and sound training system available to meet that need, to develop individuals into skilled journeyworkers, and to ensure industry an adequate supply of skilled workers. Title 29, Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), part 29, outlines the requirements for registration of acceptable apprenticeship programs for Federal purposes, and sets forth labor standards that safeguard the welfare of apprentices. Such registration may be by the U. S. Department of Labor, Office of Apprenticeship, or by a State Apprenticeship Agency recognized by the Office of Apprenticeship as the appropriate body in that State for approval of local apprenticeship programs for Federal purposes. Title 29, CFR part 30 sets forth the requirements for equal employment opportunity in apprenticeship to which all registered apprenticeship programs must adhere. The purpose of these National Guidelines for Apprenticeship Standards (National Guideline Standards) is to provide policy and guidance to local Sponsors in developing these Standards for Apprenticeship for local approval and registration. -

Military Rank Equivalency

Military rank equivalency Although GS civilians do not have military rank by virtue of their GS position, regulations include civilian and military grade equivalencies for pay and protocol comparison purposes. Military rank or civilian grade often have no bearing on supervisory precedence—generally, precedence and authority are guided by situational expertise. For example, a GS-9 is considered comparable to a first lieutenant or lieutenant (junior grade) (O-2), while a GS-15 (top of the General Schedule) is the equivalent grade of a colonel or captain (O-6). Senior Executive Service (SES) and Senior Level grades correspond for protocol purposes to flag and general officers (admirals and generals). Grade equivalencies were created by the U.S. Department of Defense for the purpose of treating civilians serving alongside the Armed Forces who have been captured as prisoners of war according to the Geneva Convention.[6] Geneva Convention Category GS MILITARY Senior Executive V: General Officer O-7 through O-10 Service GS-15 O-6 IV: Field Grade Officer GS-14/GS-13 O-5 GS-12 O-4 O-3 GS-11/GS-10 O-2 and W-4/W- III: Company Grade Officer GS-9/GS-8 3 GS-7 O-1 and W-2/W- 1 II: Non-commissioned Officer/Staff Non-Comissioned GS-6 E-7 through E-9 Officer GS-5 E-6/E-5 GS-4 E-4 I: Enlisted GS-1 through GS-3 E-1 through E-3 Grade equivalencies have also been issued by the U.S. Department of State for other purposes, such as assignment of permanent and transient housing to eligible civilian employees. -

BIOGRAPHICAL DATA BOO KK Class 2019-4 15

BBIIOOGGRRAAPPHHIICCAALL DDAATTAA BBOOOOKK Class 2019-4 15 Jul - 16 Aug 2019 National Defense University NDU PRESIDENT Vice Admiral Fritz Roegge, USN 16th President Vice Admiral Fritz Roegge is an honors graduate of the University of Minnesota with a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering and was commissioned through the Reserve Officers' Training Corps program. He earned a Master of Science in Engineering Management from the Catholic University of America and a Master of Arts with highest distinction in National Security and Strategic Studies from the Naval War College. He was a fellow of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Seminar XXI program. VADM Fritz Roegge, NDU President (Photo His sea tours include USS Whale (SSN 638), USS by NDU AV) Florida (SSBN 728) (Blue), USS Key West (SSN 722) and command of USS Connecticut (SSN 22). His major command tour was as commodore of Submarine Squadron 22 with additional duty as commanding officer, Naval Support Activity La Maddalena, Italy. Ashore, he has served on the staffs of both the Atlantic and the Pacific Submarine Force commanders, on the staff of the director of Naval Nuclear Propulsion, on the Navy staff in the Assessments Division (N81) and the Military Personnel Plans and Policy Division (N13), in the Secretary of the Navy's Office of Legislative Affairs at the U. S, House of Representatives, as the head of the Submarine and Nuclear Power Distribution Division (PERS 42) at the Navy Personnel Command, and as an assistant deputy director on the Joint Staff in both the Strategy and Policy (J5) and the Regional Operations (J33) Directorates. -

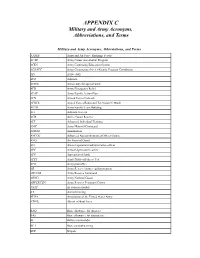

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College