Una Sola Casa: Salsa Consciente and the Poetics Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flores, Juan. “Creolité in the 'Hood: Diaspora As Source and Challenge

Centro Journal City University of New York. Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños [email protected] ISSN: 1538-6279 LATINOAMERICANISTAS 2004 Juan Flores CREOLITÉ IN THE ‘HOOD: DIASPORA AS SOURCE AND CHALLENGE Centro Journal, fall, año/vol. XVI, número 002 City University of New York. Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños New York, Latinoamericanistas pp. 282-293 Flores(v12).qxd 3/1/05 7:55 AM Page 282 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Creolité in the ‘Hood: Diaspora as Source and Challenge* JUAN FLORES ABSTRACT This article highlights the role of the Puerto Rican community in New York as the social base for the creation of Latin music of the 1960s and 1970s known as salsa, as well as its relation to the island. As implied in the subtitle, the argument is advanced that Caribbean diaspora communities need to be seen as sources of creative cultural innovation rather than as mere repositories or extensions of expressive traditions in the geographical homelands, and furthermore as a potential challenge to the assumptions of cultural authenticity typical of traditional conceptions of national culture. It is further contended that a transnational and pan- Caribbean framework is needed for a full understanding of these complex new conditions of musical migration and interaction. [Key words: salsa, transnationalism, authenticity, cultural innovation, New York music, musical migration] [ 283 ] Flores(v12).qxd 3/1/05 7:55 AM Page 284 he flight attendant let out became the basis of a widely publicized other final stop of the commute, -

Andy Gonzalez Entre Colegas Download Album Bassist Andy González, Who Brought Bounce to Latin Dance and Jazz, Dies at 69

andy gonzalez entre colegas download album Bassist Andy González, Who Brought Bounce To Latin Dance And Jazz, Dies At 69. Andy González, a New York bassist who both explored and bridged the worlds of Latin music and jazz, has died. The 69-year-old musician died in New York on Thursday night, from complications of a pre-existing illness, according to family members. Born and bred in the Bronx, Andy González epitomized the fiercely independent Nuyorican attitude through his music — with one foot in Puerto Rican tradition and the other in the cutting-edge jazz of his native New York. González's career stretched back decades, and included gigs or recordings with a who's-who of Latin dance music, including Tito Puente, Eddie Palmieri and Ray Barretto. He also played with trumpeter and Afro-Cuban jazz pioneer Dizzy Gillespie while in his twenties, as he explored the rich history of Afro-Caribbean music through books and records. In the mid-1970s, he and his brother, the trumpet and conga player Jerry González, hosted jam sessions — in the basement of their parents' home in the Bronx — that explored the folkloric roots of the then-popular salsa movement. The result was an influential album, Concepts In Unity, recorded by the participants of those sessions, who called themselves Grupo Folklórico y Experimental Nuevayorquino. Toward the end of that decade, the González brothers were part of another fiery collective known as The Fort Apache Band, which performed sporadically and went on to release two acclaimed albums in the '80s — and continued to release music through the following decades — emphasizing the complex harmonies of jazz with Afro-Caribbean underpinnings. -

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition by William D. Scott Bachelor of Arts, Central Michigan University, 2011 Master of Music, University of Michigan, 2013 Master of Arts, University of Michigan, 2015 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by William D. Scott It was defended on March 28, 2019 and approved by Mark A. Clague, PhD, Department of Music James P. Cassaro, MA, Department of Music Aaron J. Johnson, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Michael C. Heller, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by William D. Scott 2019 iii Michael C. Heller, PhD Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition William D. Scott, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 The term Latin jazz has often been employed by record labels, critics, and musicians alike to denote idioms ranging from Afro-Cuban music, to Brazilian samba and bossa nova, and more broadly to Latin American fusions with jazz. While many of these genres have coexisted under the Latin jazz heading in one manifestation or another, Panamanian pianist Danilo Pérez uses the expression “Pan-American jazz” to account for both the Afro-Cuban jazz tradition and non-Cuban Latin American fusions with jazz. Throughout this dissertation, I unpack the notion of Pan-American jazz from a variety of theoretical perspectives including Latinx identity discourse, transcription and musical analysis, and hybridity theory. -

MIC Buzz Magazine Article 10402 Reference Table1 Cuba Watch 040517 Cuban Music Is Caribbean Music Not Latin Music 15.Numbers

Reference Information Table 1 (Updated 5th June 2017) For: Article 10402 | Cuba Watch NB: All content and featured images copyrights 04/05/2017 reserved to MIC Buzz Limited content and image providers and also content and image owners. Title: Cuban Music Is Caribbean Music, Not Latin Music. Item Subject Date and Timeline Name and Topic Nationality Document / information Website references / Origins 1 Danzon Mambo Creator 1938 -- One of his Orestes Lopez Cuban Born n Havana on December 29, 1911 Artist Biography by Max Salazar compositions, was It is known the world over in that it was Orestes Lopez, Arcano's celloist and (Celloist and pianist) broadcast by Arcaño pianist who invented the Danzon Mambo in 1938. Orestes's brother, bassist http://www.allmusic.com/artist/antonio-arcaño- in 1938, was a Israel "Cachao" Lopez, wrote the arrangements which enables Arcano Y Sus mn0001534741/biography Maravillas to enjoy world-wide recognition. Arcano and Cachao are alive. rhythmic danzón Orestes died December 1991 in Havana. And also: entitled ‘Mambo’ In 29 August 1908, Havana, Cuba. As a child López studied several instruments, including piano and cello, and he was briefly with a local symphony orchestra. His Artist Biography by allmusic.com brother, Israel ‘Cachao’ López, also became a musician and influential composer. From the late 20s onwards, López played with charanga bands such as that led by http://www.allmusic.com/artist/orestes-lopez- Miguel Vásquez and he also led and co-led bands. In 1937 he joined Antonio mn0000485432 Arcaño’s band, Sus Maravillas. Playing piano, cello and bass, López also wrote many arrangements in addition to composing some original music. -

Mario Ortiz Jr

Hom e | Features | Columns | Hit Parades | Reviews | Calendar | News | Contacts | Shopping | E-Back Issues NOVEMBER 2009 ISSUE FROM THE EDITOR Welcome to the home of Latin Beat Magazine Digital! After publishing Latin Beat Magazine for 19 years in both print and online, Yvette and I have decided to continue pursuing our passion for Latin music with a digital version only. Latin Beat Magazine will continue its coverage of Latin music through monthly in-depth articles, informative Streaming Music columns, concert and CD reviews, and extensive news and information for everyone. Access to Somos Son www.lbmo.com or www.latinbeatmagazine.com (Latin Beat Magazine Online) is free for a limited Bilongo time only. Windows Media Quicktime Your events and new music submissions are welcome and encouraged by emailing to: [email protected]. The Estrada Brothers Latin beat is number one in the world of authentic Latin music. For advertising opportunities in Mr. Ray lbmo.com, call (310) 516-6767 or request advertising information at Windows Media [email protected]. Quicktime Back issues are still in print! Please order thru the Shopping section! Manny Silvera Bassed in America This issue of Latin Beat Magazine Volume 19, Number 9, November 2009, is our annual "Special Windows Media Percussion/Drum Issue", which celebrates "National Drum Month" throughout North America. Our Quicktime featured artist this month is Puerto Rican percussionist/bandleader Richie Flores. In addition, also featured are Poncho Sanchez (who's enjoying the release of his latest production Psychedelic Blues), and trumpeter/bandleader Mario Ortiz Jr. (who has one of the hottest salsa Bobby Matos productions of the year). -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

Grover Washington, Jr. Feels So Good Mp3, Flac, Wma

Grover Washington, Jr. Feels So Good mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Feels So Good Country: Canada Released: 1981 Style: Soul-Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1344 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1563 mb WMA version RAR size: 1756 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 407 Other Formats: WMA AA XM MP3 VOC TTA WAV Tracklist Hide Credits The Sea Lion A1 5:59 Written-By – Bob James Moonstreams A2 5:58 Written-By – Grover Washington, Jr. Knucklehead A3 7:51 Written-By – Grover Washington, Jr. It Feels So Good B1 8:50 Written-By – Ralph MacDonald, William Salter Hydra B2 9:07 Written-By – Grover Washington, Jr. Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Quality Records Limited Distributed By – Quality Records Limited Credits Arranged By – Bob James Bass – Gary King (tracks: A1 to A3), Louis Johnson (tracks: B1, B2) Bass Trombone – Alan Ralph*, Dave Taylor* Cello – Charles McCracken, Seymour Barab Drums – Jimmy Madison (tracks: A3), Kenneth "Spider Webb" Rice* (tracks: B1, B2), Steve Gadd (tracks: A1, A2) Electric Piano – Bob James Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder English Horn – Sid Weinberg* Flugelhorn – John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Randy Brecker, Bob Millikan* Guitar – Eric Gale Oboe – Sid Weinberg* Percussion – Ralph MacDonald Piano – Bob James Producer – Creed Taylor Saxophone [Soprano] – Grover Washington, Jr. Saxophone [Tenor] – Grover Washington, Jr. Synthesizer – Bob James Trombone – Barry Rogers Trumpet – John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Randy Brecker, Bob Millikan* Viola – Al Brown*, Manny Vardi* Violin – Barry Finclair, David Nadien, Emanuel Green, Guy Lumia, Harold Kohon, Harold Lookofsky*, Lewis Eley, Max Ellen, Raoul Poliakin Notes Recorded at Van Gelder Studios, May & July 1975 Manufactured and distributed in Canada M5-177V1 on cover & spine M 177V on labels Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Grover Feels So Good KU-24 S1 Kudu KU-24 S1 US 1975 Washington, Jr. -

CBS International's Study

BEFORE THE COPYRIGHT ROYALTY TRIBUNAL WASHINGTON, D.C. In the Matter of ) ) 1984 Juke-Box Royalty ) Docket No. Distribution Proceedings ) SUPPLEMENTAL STATEMENT PURSUANT TO 37 C.F.R. SECTION 305.4 Asociacion de Compositores y Editores de Musica Latino- americana ("ACEMLA"), having duly filed a claim of entitlement pursuant to 37 C.F.R. Sections 305.2, 305.3 and having filed a statement pursuant to 37 C.F.R. Section 305.4 on November 5, 1985, submits this supplemental statement and documentation on November 5th filing. 1. In Paragraph 4 of ACEMLA's November 5th Statement, I ACEMLA cited a study undertaken by Discos CBS International as cited in the publication "Music Video Retailer" in January 1983. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is the article concerning Discos CBS International's study. 2. In Paragraph 5 of ACEMLA's November 5th Statement, an article entitled "Spanish Speaking Market on the Move" from the January 1983 issue of "Music Video Retailer" was also cited. This article is attached as Exhibit 2. 3. Paragraph 7 of ACEMLA's November 5th Statement noted that "throughout 1984 a significant number of hits whose copy rights were owned or administered by ACEMLA appeared in trade charts both in 45 rpm or LP form. These trade charts reflect the major songs in the United States Hispanic market." 4. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 are hit Latin record charts from the publication "Canales", published in New York City, for the months of January 1984 through November 1984. The circled numbers next to the title and the circled titles in- dicate titles that are in in ACEMLA's catalogue. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Choreographing Politics, Dancing Modernity: Ballet and Modern Dance in the Construction of Modern México (1919-1940) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8z45r94t Author Reynoso, Jose Luis Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Choreographing Politics, Dancing Modernity: Ballet and Modern Dance in the Construction of Modern México (1919-1940) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Jose Luis Reynoso 2012 © Copyright by Jose Luis Reynoso 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Choreographing Politics, Dancing Modernity: Ballet and Modern Dance in the Construction of Modern México (1919-1940) by Jose Luis Reynoso Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair In this dissertation, I analyze the pivotal role that ballet and modern dance played in the construction of modern México during the development of its post-revolutionary history and culture from 1919 to 1940. In this doctoral research, I approach dance as a means of knowledge production that contributes to shaping the cultural contexts in which individual and collective identities are produced while perpetuating systems of sociopolitical and economic domination and/or offering alternatives to restructure unequal power relations. As an organizing principle, this dissertation presupposes that dances always enact, explicitly and/or implicitly, sets of political assumptions that affect the bodies that participate by dancing or by watching dance. In other words, I examine how dance represents race, class, gender, and sexuality; how corporeal ii difference is arranged in space; what does the dance say about human relations; and how subjectivity is constructed through dance training and performing on stage. -

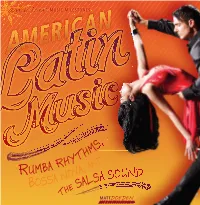

Rumba Rhythms, Salsa Sound

MUSIC MILESTONES AMERICAN MS, RUMBA RHYTH ND BOSSA NOVA, A THE SALSA SOUND MATT DOEDEN This Page Left Blank Intentionally MUSIC MILESTONES AMERICAN MS, RUMBA RHYTH ND BOSSA NOVA, A HE SALSA SOUND T MATT DOEDEN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY BOOKS MINNEAPOLIS NOTE TO READERS: some songs and music videos by artists discussed in this book contain language and images that readers may consider offensive. Copyright © 2013 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review. Twenty-First Century Books A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. 241 First Avenue North Minneapolis, MN 55401 U.S.A. Website address: www.lernerbooks.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Doeden, Matt. American Latin music : rumba rhythms, bossa nova, and the salsa sound / by Matt Doeden. p. cm. — (American music milestones) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–7613–4505–3 (lib. bdg. : alk. paper) 1. Popular music—United States—Latin American influences. 2. Dance music—Latin America—History and criticism. 3. Music— Latin America—History and criticism. 4. Musicians—Latin America. 5. Salsa (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3477.D64 2013 781.64089’68073—dc23 2012002074 Manufactured in the United States of America 1 – CG – 7/15/12 Building the Latin Sound www 5 Latin Fusions www 21 Sensations www 33 www The Latin Explosion 43 Glossary w 56 Source Notes w 61 Timeline w 57 Selected Bibliography w 61 Mini Bios w 58 Further Reading, w Websites, Latin Must-Haves 59 and Films w 62 w Major Awards 60 Index w 63 BUILDING THE Pitbull L E F T, Rodrigo y Gabriela R IG H T, and Shakira FAR RIGHT are some of the big gest names in modern Latin music. -

John Bailey Randy Brecker Paquito D'rivera Lezlie Harrison

192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:36 AM Page 1 E Festival & Outdoor THE LATIN SIDE 42 Concert Guide OF HOT HOUSE P42 pages 30-41 June 2018 www.hothousejazz.com Smoke Jazz & Supper Club Page 17 Blue Note Page 19 Lezlie Harrison Paquito D'Rivera Randy Brecker John Bailey Jazz Forum Page 10 Smalls Jazz Club Page 10 Where To Go & Who To See Since 1982 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:36 AM Page 2 2 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 3 3 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 4 4 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 5 5 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 6 6 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 7 7 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 8 8 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 11:45 AM Page 9 9 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 10 WINNING SPINS By George Kanzler RUMPET PLAYERS ARE BASI- outing on soprano sax. cally extroverts, confident and proud Live 1988, Randy Brecker Quintet withT a sound and tone to match. That's (MVDvisual, DVD & CD), features the true of the two trumpeters whose albums reissue of a long out-of-print album as a comprise this Winning Spins: John Bailey CD, accompanying a previously unreleased and Randy Brecker. Both are veterans of DVD of the live date, at Greenwich the jazz scene, but with very different Village's Sweet Basil, one of New York's career arcs. John has toiled as a first-call most prominent jazz clubs in the 1980s trumpeter for big bands and recording ses- and 1990s. -

Significado Y Antecedentes Del Movimiento Militar De 1924

SIGNIFICADO Y ANTECEDENTES DEL MOVIMIENTO MILITAR DE 1924. René Millar Carvacho INDICE Página PRÓLOGO…………………………………………………………………………………… 1 CAPÍTULO I. Los políticos y la frustración nacional 1891 – 1924………………………… 3 CAPÍTULO II. Las Fuerzas Armadas entre 1891 – 1920…………………………...……… 36 1.- Situación profesional y económica del personal de las Fuerzas Armadas……………….. 36 2.- Situación disciplinaria de las Fuerzas Armadas………………………………………….. 54 CAPÍTULO III. Las Fuerzas Armadas entre 1920 – 1924………………………………….. 73 1.- Alessandri y las Fuerzas Armadas…………………………………….………………….. 73 2.- La oposición y las Fuerzas Armadas………………………………….………………….. 92 3.- El pronunciamiento de septiembre……………………………………..………………… 96 1 SIGNIFICADO Y ANTECEDENTES DEL MOVIMIENTO MILITAR DE 1924∗ René Millar Carvacho Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile PROLOGO El 5 de septiembre de 1924 las Fuerzas Armadas efectuaron una intervención política que significó la caída del gobierno de Arturo Alessandri Palma y el término del régimen parlamentario. No resulta fácil explicar esa situación si se considera que los militares gozaban de gran fama por su profesionalismo y por mantenerse apegados al principio de no deliberación. Por otra parte, el parlamentarismo era el sistema de gobierno que el país practicaba sin restricciones desde 1891 y toda la clase política, salvo muy pocas excepciones, lo valoraba como el régimen más idóneo para garantizar las libertades y favorecer el progreso y no estaba dispuesto a cambiarlo. A debe sumarse la figura del Primer Mandatario de la época, que gozaba de una gran popularidad merced a sus dotes de caudillo y a sus propuestas de renovación y populistas. En este trabajo nosotros partimos de la hipótesis de que buena parte de esas imágenes existentes respecto a la institucionalidad del país no se ajustaban del todo a la realidad.