Muse49.Pdf (5.350Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estudos De Egiptologia Vi

ESTUDOS DE EGIPTOLOGIA VI 2ª edição SESHAT - Laboratório de Egiptologia do Museu Nacional Rio de Janeiro – Brasil 2019 SEMNA – Estudos de Egiptologia VI 2ª edição Antonio Brancaglion Junior Cintia Gama-Rolland Gisela Chapot Organizadores Seshat – Laboratório de Egiptologia do Museu Nacional/Editora Klínē Rio de Janeiro/Brasil 2019 Este trabalho está licenciado com uma Licença Creative Commons - Atribuição-Não Comercial- Compartilha Igual 4.0 Internacional. Capa: Antonio Brancaglion Jr. Diagramação e revisão: Gisela Chapot Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Ficha Catalográfica B816s BRANCAGLION Jr., Antonio. Semna – Estudos de Egiptologia VI/ Antonio Brancaglion Jr., Cintia Gama-Rolland, Gisela Chapot., (orgs.). 2ª ed. – Rio de Janeiro: Editora Klínē,2019. 179 f. Bibliografia. ISBN 978-85-66714-12-8 1. Egito antigo 2. Arqueologia 3. História 4. Coleção I. Título CDD 932 CDU 94(32) I. Título. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Museu Nacional Programa de Pós-graduação em Arqueologia CDD 932 Seshat – Laboratório de Egiptologia CDU 94(32) Quinta da Boa Vista, s/n, São Cristóvão Rio de Janeiro, RJ – CEP 20940-040 Editora Klínē 2 Sumário APRESENTAÇÃO ..................................................................................................................... 4 OLHARES SOBRE O EGITO ANTIGO: O CASO DA DANÇA DO VENTRE E SUA PROFISSIONALIZAÇÃO ........................................................................................................... 5 LUTAS DE CLASSIFICAÇÕES NO EGITO ROMANO (30 AEC - 284 EC): UMA CONTRIBUIÇÃO A PARTIR DA -

In Ancient Egypt

THE ROLE OF THE CHANTRESS ($MW IN ANCIENT EGYPT SUZANNE LYNN ONSTINE A thesis submined in confonnity with the requirements for the degm of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civiliations University of Toronto %) Copyright by Suzanne Lynn Onstine (200 1) . ~bsPdhorbasgmadr~ exclusive liceacc aiiowhg the ' Nationai hiof hada to reproduce, loan, distnia sdl copies of this thesis in miaof#m, pspa or elccmnic f-. L'atm criucrve la propri&C du droit d'autear qui protcge cette thtse. Ni la thèse Y des extraits substrrntiets deceMne&iveatetreimprimCs ouraitnmcrtrepoduitssanssoai aut&ntiom The Role of the Chmaes (fm~in Ancient Emt A doctorai dissertacion by Suzanne Lynn On*, submitted to the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 200 1. The specitic nanire of the tiUe Wytor "cimûes", which occurrPd fcom the Middle Kingdom onwatd is imsiigated thrwgh the use of a dalabase cataloging 861 woinen whheld the title. Sorting the &ta based on a variety of delails has yielded pattern regatding their cbnological and demographical distribution. The changes in rhe social status and numbers of wbmen wbo bore the Weindicale that the Egyptians perceivecl the role and ams of the titk âiffefcntiy thugh tirne. Infomiation an the tities of ihe chantressw' family memkrs bas ailowed the author to make iderences cawming llse social status of the mmen who heu the title "chanms". MiMid Kingdom tifle-holders wverc of modest backgrounds and were quite rare. Eighteenth DMasty women were of the highest ranking families. The number of wamen who held the titk was also comparatively smaii, Nimeenth Dynasty women came [rom more modesi backgrounds and were more nwnennis. -

The Burial of the Urban Poor in Italy in the Late Republic and Early Empire

Death, disposal and the destitute: The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Republic and early Empire Emma-Jayne Graham Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Sheffield December 2004 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk The following have been excluded from this digital copy at the request of the university: Fig 12 on page 24 Fig 16 on page 61 Fig 24 on page 162 Fig 25 on page 163 Fig 26 on page 164 Fig 28 on page 168 Fig 30on page 170 Fig 31 on page 173 Abstract Recent studies of Roman funerary practices have demonstrated that these activities were a vital component of urban social and religious processes. These investigations have, however, largely privileged the importance of these activities to the upper levels of society. Attempts to examine the responses of the lower classes to death, and its consequent demands for disposal and commemoration, have focused on the activities of freedmen and slaves anxious to establish or maintain their social position. The free poor, living on the edge of subsistence, are often disregarded and believed to have been unceremoniously discarded within anonymous mass graves (puticuli) such as those discovered at Rome by Lanciani in the late nineteenth century. This thesis re-examines the archaeological and historical evidence for the funerary practices of the urban poor in Italy within their appropriate social, legal and religious context. The thesis attempts to demonstrate that the desire for commemoration and the need to provide legitimate burial were strong at all social levels and linked to several factors common to all social strata. -

589 Thesis in the Date of Tomb TT 254 Verification Through Analysis Of

Thesis in The Date Of Tomb TT 254 Verification Through Analysis of its Scenes Thesis in The Date of Tomb TT 254 Verification through Analysis of its Scenes Sahar Mohamed Abd el-Rahman Ibrahim Faculty of Archeology, Cairo University, Egypt Abstract: This paper extrapolates and reaches an approximate date of the TOMB of TT 254, the tomb of Mosi (Amenmose) (TT254), has not been known to Egyptologists until year 1914, when it was taken up from modern occupants by the Antiquities Service, The tomb owner is Mosi , the Scribe of the treasury and custodian of the estate of queen Tiye in the domain of Amun This tomb forms with two other tombs (TT294-TT253) a common courtyard within Al-Khokha necropolis. Because the Titles/Posts of the owner of this tomb indicated he was in charge of the estate of Queen Tiye, no wonder a cartouche of this Queen were written among wall paintings. Evidently, this tomb’s stylistic features of wall decorations are clearly influenced by the style of Amarna; such as the male figures with prominent stomachs, and elongated heads, these features refer that tomb TT254 has been finished just after the reign of Amenhotep IV (Akhenatun). Table stands between the deceased and Osiris which is divided into two parts: the first part (as a tray) is loading with offerings, then the other is a bearer which consisted of two stands shaped as pointed pyramids… based on the connotations: 1- Offerings tables. 2- Offerings Bearers. 3- Anubis. 4- Mourners. 5- Reclamation of land for cultivation. 6- Banquet in some noble men tombs at Thebes through New Kingdom era. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

Urban Development at Rome's Porta Esquilina and Church of San Vito

This is the first page only. On how to acquire the full article please click this link. Urban development at Rome’s Porta Esquilina and church of San Vito over the longue durée Margaret Andrews and Seth Bernard San Vito’s modern location on the Esquiline betrays little of the importance of the church’s site in the pre-modern city (fig. 1). The small church was begun under Pope Six- tus IV for the 1475 jubilee and finished two years later along what was at that time the main route between Santa Maria Maggiore and the Lateran.1 Modern interventions, however, and particularly the creation of the quartiere Esquilino in the late 19th c., changed the traffic patterns entirely. An attempt was made shortly thereafter to connect it with the new via Carlo Alberto by reversing the church’s orientation and constructing a new façade facing this modern street. This façade, built into the original 15th-c. apse, was closed when the church was returned to its original orientation in the 1970s, and, as a result, San Vito today appears shuttered.2 In the ancient and mediaeval periods, by contrast, San Vito was set at a key point in Rome’s eastern environs. It was at this very spot that the main route from the Forum, leading eastward up the Argiletum and clivus Suburanus, crossed the Republican city-walls at the Porta Esquilina to become the consular via Tiburtina (fig. 2). The central of the original three bays of the Augustan arch marking the Porta Esquilina still stands against the W wall of the early modern church, bearing a rededication in A.D. -

Problems in Athenian Democracy 510-480 BC Exiles

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1971 Problems in Athenian Democracy 510-480 B. C. Exiles: A Case of Political Irrationality Peter Karavites Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Karavites, Peter, "Problems in Athenian Democracy 510-480 B. C. Exiles: A Case of Political Irrationality" (1971). Dissertations. Paper 1192. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1192 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1971 Peter. Karavites PROBLEMS IN ATHENIAN DEMOCRACY 510-480 B.C. EXILES A Case of Political Irrationality A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty o! the Department of History of Loyola University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy b;y Peter Karavites ?ROBLEt'.n IN ATP.EHIA:rT n:s::ocRACY 5'10-480 n.c. EXIL:ffi: A case in Politioal Irrationality Peter·KARAVIT~ Ph.D. Loyola UniVGl'Sity, Chicago, 1971 This thesis is m attempt to ev"aluate the attitude of the Athenian demos during the tormative years of the Cleisthenian democracy. The dissertation tries to trace the events of the period from the mpul sion of Hippian to the ~ttle of Sal.amis. Ma.tural.ly no strict chronological sequence can be foll.amtd.. The events are known to us only f'ragmen~. some additional archaeological Wormation has trickled dcmn to us 1n the last tro decad.all 11h1ch shed light on the edating historical data prO\Tided ma:1nly by Herodotus md Arletotle. -

La Chiesa E Il Quartiere Di San Francesco a Pisa

Edizioni dell’Assemblea 206 Ricerche Franco Mariani - Nicola Nuti La chiesa e il quartiere di San Francesco a Pisa Giugno 2020 CIP (Cataloguing in Publication) a cura della Biblioteca della Toscana Pietro Leopoldo La chiesa e il quartiere di San Francesco a Pisa / Franco Mariani, Nicola Nuti ; [presentazioni di Eugenio Giani, Michele Conti, Fra Giuliano Budau]. - [Firenze] : Consiglio regionale della Toscana, 2020 1. Mariani, Franco 2. Nuti, Nicola 3. Giani, Eugenio 4. Conti, Michele 5. Budau, Giuliano 726.50945551 Chiesa di San Francesco <Pisa> Volume in distribuzione gratuita In copertina: facciata della chiesa di San Francesco a Pisa del Sec. XIII, Monumento Nazionale e di proprietà dello Stato. Foto di Franco Mariani. Consiglio regionale della Toscana Settore “Rappresentanza e relazioni istituzionali ed esterne. Comunicazione, URP e Tipografia” Progetto grafico e impaginazione: Patrizio Suppa Pubblicazione realizzata dal Consiglio regionale della Toscana quale contributo ai sensi della l.r. 4/2009 Giugno 2020 ISBN 978-88-85617-66-7 Sommario Presentazioni Eugenio Giani, Presidente del Consiglio regionale della Toscana 11 Michele Conti, Sindaco di Pisa 13 Fra Giuliano Budau, Padre Guardiano, Convento di San Francesco a Pisa 15 Prologo 17 Capitolo I Il quartiere di San Francesco a Pisa 19 Capitolo II Viaggio all’interno del quartiere 29 Capitolo III L’arrivo dei Francescani a Pisa 33 Capitolo IV I Frati Minori Conventuali 45 Capitolo V L’Inquisizione 53 Capitolo VI La chiesa di San Francesco 57 Capitolo VII La chiesa nelle guide turistiche -

I General for Place Names See Also Maps and Their Keys

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12098-2 - Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology Edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw Index More information Index I General For place names see also maps and their keys. AAS see atomic absorption specrophotometry Tomb E21 52 aerenchyma 229 Abbad region 161 Tomb W2 315 Aeschynomene elaphroxylon 336 Abdel ‘AI, 1. 51 Tomb 113 A’09 332 Afghanistan 39, 435, 436, 443 abesh 591 Umm el-Qa’ab, 63, 79, 363, 496, 577, 582, African black wood 338–9, 339 Abies 445 591, 594, 631, 637 African iron wood 338–9, 339 A. cilicica 348, 431–2, 443, 447 Tomb Q 62 agate 15, 21, 25, 26, 27 A. cilicica cilicica 431 Tomb U-j 582 Agatharchides 162 A. cilicica isaurica 431 Cemetery U 79 agathic acid 453 A. nordmanniana 431 Abyssinia 46 Agathis 453, 464 abietane 445, 454 acacia 91, 148, 305, 335–6, 335, 344, 367, 487, Agricultural Museum, Dokki (Cairo) 558, 559, abietic acid 445, 450, 453 489 564, 632, 634, 666 abrasive 329, 356 Acacia 335, 476–7, 488, 491, 586 agriculture 228, 247, 341, 344, 391, 505, Abrak 148 A. albida 335, 477 506, 510, 515, 517, 521, 526, 528, 569, Abri-Delgo Reach 323 A. arabica 477 583, 584, 609, 615, 616, 617, 628, 637, absorption spectrophotometry 500 A. arabica var. adansoniana 477 647, 656 Abu (Elephantine) 323 A. farnesiana 477 agrimi 327 Abu Aggag formation 54, 55 A. nilotica 279, 335, 354, 367, 477, 488 A Group 323 Abu Ghalib 541 A. nilotica leiocarpa 477 Ahmose (Amarna oªcial) 115 Abu Gurob 410 A. -

Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2002 Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B. Smith Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE ALBERTO ARINGHIERI AND THE CHAPEL OF SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST: PATRONAGE, POLITICS, AND THE CULT OF RELICS IN RENAISSANCE SIENA By TIMOTHY BRYAN SMITH A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2002 Copyright © 2002 Timothy Bryan Smith All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Timothy Bryan Smith defended on November 1 2002. Jack Freiberg Professor Directing Dissertation Mark Pietralunga Outside Committee Member Nancy de Grummond Committee Member Robert Neuman Committee Member Approved: Paula Gerson, Chair, Department of Art History Sally McRorie, Dean, School of Visual Arts and Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the abovenamed committee members. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I must thank the faculty and staff of the Department of Art History, Florida State University, for unfailing support from my first day in the doctoral program. In particular, two departmental chairs, Patricia Rose and Paula Gerson, always came to my aid when needed and helped facilitate the completion of the degree. I am especially indebted to those who have served on the dissertation committee: Nancy de Grummond, Robert Neuman, and Mark Pietralunga. -

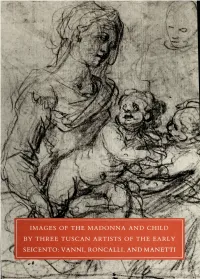

IMAGES of the MADONNA and CHILD by THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS of the EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, and MANETTI Digitized by Tine Internet Arcliive

r.^/'v/\/ f^jf ,:\J^<^^ 'Jftf IMAGES OF THE MADONNA AND CHILD BY THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS OF THE EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, AND MANETTI Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/innagesofmadonnacOObowd OCCASIONAL PAPERS III Images of the Madonna and Child by Three Tuscan Artists of the Early Seicento: Vanni, Roncalli, and Manetti SUSAN E. WEGNER BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART BRUNSWICK, MAINE Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 86-070511 ISBN 0-91660(>-10-4 Copyright © 1986 by the President and Trustees of Bowdoin College All rights reserved Designed by Stephen Harvard Printed by Meriden-Stinehour Press Meriden, Connecticut, and Lunenburg, Vermont , Foreword The Occasional Papers of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art began in 1972 as the reincarnation of the Bulletin, a quarterly published between 1960 and 1963 which in- cluded articles about objects in the museum's collections. The first issue ofthe Occasional Papers was "The Walker Art Building Murals" by Richard V. West, then director of the museum. A second issue, "The Bowdoin Sculpture of St. John Nepomuk" by Zdenka Volavka, appeared in 1975. In this issue, Susan E. Wegner, assistant professor of art history at Bowdoin, discusses three drawings from the museum's permanent collection, all by seventeenth- century Tuscan artists. Her analysis of the style, history, and content of these three sheets adds enormously to our understanding of their origins and their interconnec- tions. Professor Wegner has given very generously of her time and knowledge in the research, writing, and editing of this article. Special recognition must also go to Susan L. -

'Scènes De Gynécées' Figured Ostraca from New Kingdom Egypt: Iconography and Intent

‘Scènes de Gynécées’ Figured Ostraca from New Kingdom Egypt: iconography and intent Joanne Backhouse Archaeopress Egyptology 26 Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-345-4 ISBN 978-1-78969-346-1 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and Joanne Backhouse 2020 Cover image: Drawing on limestone. WoB.36: Louvre E 14337 (photograph by Joanne Backhouse). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Severn, Gloucester This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................................ iv General Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................................ vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................................viii Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... ix Chapter 1 Deir el-Medina: