Barocci's Immacolata Within 'Franciscan' Umbria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Artwork Tear Sheet

Federico Barocci (Urbino, 1535 – Urbino, 1612) Man Reading, c. 1605–1607 Oil on canvas (old relining) 65.5 x 49.5 cm On the back, label printed in red ink: Emo / Gio Battist[a] Provenance – Collection of Cardinal Antonio Barberini. Inventory 1671: "130 – Un quadro di p.mi 3 ½ inc.a di Altezza, e p.mi 3 di largha’ Con Mezza figura con il Braccio incupido [incompiuto] appogiato al capo, e nell’altra Un libro, opera di Lodovico [sic] Barocci Con Cornice indorata n° 1-130" – Paris, Galerie Tarantino until 2018 Literature – Andrea Emiliani, "Federico Barocci. Étude d’homme lisant", in exh. cat. Rome de Barocci à Fragonard (Paris: Galerie Tarantino, 2013), pp. 18–21, repr. – Andrea Emiliani, La Finestra di Federico Barocci. Per una visione cristologica del paesaggio urbano, Bologne (Faenza: Carta Bianca, 2016), p. 118, repr. Trained in the Mannerist tradition in Urbino and Rome, Federico Barocci demonstrated from the outset an astonishing capacity to assimilate the art of the masters. Extracting the essentials from a pantheon comprising Raphael, the Venetians and Correggio, he perfected a language at once profoundly personal and attuned to the issues raised by the Counter-Reformation. After an initial grounding in his native Urbino by Battista Franco and his uncle, Bartolommeo Genga, he went to Rome under the patronage of Cardinal della Rovere and studied Raphael while working with Taddeo Zuccaro. During a second stay in Rome in 1563 he was summoned by Pope Pius VI to help decorate the Casino del Belvedere at the Vatican, but in the face of the hostility his success triggered on the Roman art scene he ultimately fled the city – the immediate cause, it was said, being an attempted poisoning by rivals whose aftereffects were with him for the rest of his life. -

Girolamo Muziano, Scipione Pulzone, and the First Generation of Jesuit Art

journal of jesuit studies 6 (2019) 196-212 brill.com/jjs Girolamo Muziano, Scipione Pulzone, and the First Generation of Jesuit Art John Marciari The Morgan Library & Museum, New York [email protected] Abstract While Bernini and other artists of his generation would be responsible for much of the decoration at the Chiesa del Gesù and other Jesuit churches, there was more than half a century of art commissioned by the Jesuits before Bernini came to the attention of the order. Many of the early works painted in the 1580s and 90s are no longer in the church, and some do not even survive; even a major monument like Girolamo Muzia- no’s Circumcision, the original high altarpiece, is neglected in scholarship on Jesuit art. This paper turns to the early altarpieces painted for the Gesù by Muziano and Scipione Pulzone, to discuss the pictorial and intellectual concerns that seem to have guided the painters, and also to some extent to speculate on why their works are no longer at the Gesù, and why these artists are so unfamiliar today. Keywords Jesuit art – Il Gesù – Girolamo Muziano – Scipione Pulzone – Federico Zuccaro – Counter-Reformation – Gianlorenzo Bernini Visitors to the Chiesa del Gesù in Rome, or to the recent exhibition of Jesuit art at Fairfield University,1 might naturally be led to conclude that Gianlorenzo 1 Linda Wolk-Simon, ed., The Holy Name: Art of the Gesù; Bernini and His Age, Exh. cat., Fair- field University Art Museum, Early Modern Catholicism and the Visual Arts 17 (Philadelphia: Saint Joseph’s University Press, 2018). -

What Remains of Titan in Le Marche Tiziano Who Is Name in English Is Titian, Is Well Known in England and in Many Countries

What remains of Titan in Le marCHE Tiziano who is name in English is Titian, is well Known in England and in many countries. His canvases have been displayed in many museums because he worked in many countries of Europe and in Le Marche region. Some of his paintings can be seen by cruise passengers in the summer season because the local museum and Saint Domenic church are open in Ancona. In our region there are unsual imagines because they have deep colours. If we didn’t have his pictures we couldn’t explain many things about our artistic culture between mannerism and the Baroque period. In fact artists used to paint their images using light colours such as yellow, white, green ect.. He influenced the style of Federico Zuccari in Spain who was commissioned by Philip II to paint an “Annunciation”. His painting was destroyed by the Imperor due to its deep colours. He had been chosen because of his bright colours. Also Painters were used to paint their subjects on canvas which was made with a herringbone texture. Princes, Popes and Doges were portrayed by Titian. His career is characterized by a lot of artistic experimentation. After a few years in Venice working with Giovanni Bellini, He began to paint with big mastery. Also, He met Giorgione from Castelfranco who renewed the artistic culture in the city of Venice. We can say that Titian was the “true and great” master. In fact, He collaborated with Giorgione at “Fondaco dei Tedeschi a Rialto”. He used to paint with bright colours because it gave dynamism to his style. -

La Chiesa E Il Quartiere Di San Francesco a Pisa

Edizioni dell’Assemblea 206 Ricerche Franco Mariani - Nicola Nuti La chiesa e il quartiere di San Francesco a Pisa Giugno 2020 CIP (Cataloguing in Publication) a cura della Biblioteca della Toscana Pietro Leopoldo La chiesa e il quartiere di San Francesco a Pisa / Franco Mariani, Nicola Nuti ; [presentazioni di Eugenio Giani, Michele Conti, Fra Giuliano Budau]. - [Firenze] : Consiglio regionale della Toscana, 2020 1. Mariani, Franco 2. Nuti, Nicola 3. Giani, Eugenio 4. Conti, Michele 5. Budau, Giuliano 726.50945551 Chiesa di San Francesco <Pisa> Volume in distribuzione gratuita In copertina: facciata della chiesa di San Francesco a Pisa del Sec. XIII, Monumento Nazionale e di proprietà dello Stato. Foto di Franco Mariani. Consiglio regionale della Toscana Settore “Rappresentanza e relazioni istituzionali ed esterne. Comunicazione, URP e Tipografia” Progetto grafico e impaginazione: Patrizio Suppa Pubblicazione realizzata dal Consiglio regionale della Toscana quale contributo ai sensi della l.r. 4/2009 Giugno 2020 ISBN 978-88-85617-66-7 Sommario Presentazioni Eugenio Giani, Presidente del Consiglio regionale della Toscana 11 Michele Conti, Sindaco di Pisa 13 Fra Giuliano Budau, Padre Guardiano, Convento di San Francesco a Pisa 15 Prologo 17 Capitolo I Il quartiere di San Francesco a Pisa 19 Capitolo II Viaggio all’interno del quartiere 29 Capitolo III L’arrivo dei Francescani a Pisa 33 Capitolo IV I Frati Minori Conventuali 45 Capitolo V L’Inquisizione 53 Capitolo VI La chiesa di San Francesco 57 Capitolo VII La chiesa nelle guide turistiche -

Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2002 Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B. Smith Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE ALBERTO ARINGHIERI AND THE CHAPEL OF SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST: PATRONAGE, POLITICS, AND THE CULT OF RELICS IN RENAISSANCE SIENA By TIMOTHY BRYAN SMITH A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2002 Copyright © 2002 Timothy Bryan Smith All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Timothy Bryan Smith defended on November 1 2002. Jack Freiberg Professor Directing Dissertation Mark Pietralunga Outside Committee Member Nancy de Grummond Committee Member Robert Neuman Committee Member Approved: Paula Gerson, Chair, Department of Art History Sally McRorie, Dean, School of Visual Arts and Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the abovenamed committee members. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I must thank the faculty and staff of the Department of Art History, Florida State University, for unfailing support from my first day in the doctoral program. In particular, two departmental chairs, Patricia Rose and Paula Gerson, always came to my aid when needed and helped facilitate the completion of the degree. I am especially indebted to those who have served on the dissertation committee: Nancy de Grummond, Robert Neuman, and Mark Pietralunga. -

Stephen Ongpin Fine Art

STEPHEN ONGPIN FINE ART GIOVANNI BATTISTA CASTELLO, CALLED IL GENOVESE Genoa 1547-1639 Genoa Saint Jerome in Prayer Bodycolour, heightened with gold, on vellum. 149 x 117 mm. (5 7/8 x 4 5/8 in.) Provenance Private collection. Literature Elena de Laurentis, ‘Il pio Genovese: Giovanni Battista Castello’, Alumina, April-June 2012, illustrated p.29. Giovanni Battista Castello apprenticed in the studio of Luca Cambiaso in Genoa, probably in the 1560s, following an initial period of training with his father Antonio, a goldsmith. (His younger brother, the painter Bernardo Castello, also studied with Cambiaso.) Castello began his career as a goldsmith and indeed it was not until 1579, when he was already in his thirties, that he began working primarily as an illuminator and miniature painter. Certainly, his grounding in the goldsmith’s art is evident in the jewel- like qualities of much of his oeuvre. His earliest works are indebted to the example of the miniaturist Giulio Clovio and, through him, Michelangelo. Castello became one of the foremost miniaturists of the day, and his colourful religious scenes, usually on vellum, were widely admired and much praised. Indeed, his fame spread as far as Spain, where around 1583 he was summoned by Philip II to work on the illumination of several choir books for the Royal monastery of El Escorial. Although Castello apparently produced over two hundred choir book illuminations (‘corali miniati’) while at the Escorial, none of these appear to have survived. Castello was back in Genoa by 1586, and for much of the remainder of his long career – he died when he was in his nineties - was at the peak of his artistic activity. -

News Release the Metropolitan Museum of Art

news release The Metropolitan Museum of Art For Release: Contact: Immediate Harold Holzer Norman Keyes, Jr. SCHEDULE OF EXHIBITIONS - JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1994 EDITORS PLEASE NOTE: Information provided below is subject to change. To confirm scheduling and dates, call the Communications Department (212) 570-3951. For Upcoming Exhibitions, see page 3; Continuing Exhibitions, page 8; New and Upcoming Permanent Installations, page 10; Traveling Exhibitions, page 12; Visitor Information, pages 13, 14. EDITORS PLEASE NOTE: On April 13, the Metropolitan will open for the first time sixteen permanent galleries embracing the arts of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Tibet, Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Burma, and Malaysia. The new Florence and Herbert Irving Galleries for the Arts of South and Southeast Asia will include some 1300 works, most of which have not been publicly displayed at the Museum before. Dates of several special exhibitions have been extended, including Church's Great Picture: The Heart of the Andes (through January 30); A Decade of Collecting: Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 1984- 1993 (through January 30); and Tang Family Gifts of Chinese Painting (indefinite close). Museum visitors may now for the first time enter the vestibule or pronaos of the Temple of Dendur in The Sackler Wing, and peer into the antechamber and sanctuary further within this Nubian temple, which is one of the most popular attractions at the Metropolitan. Three steps have been installed on the south side to facilitate closer study of the monument and its wall reliefs; a ramp has been added on the eastern end for wheelchair access. (Press Viewing: Wednesday, January 19, 10:00 a.m.-noon). -

Exhibition Checklist: a Superb Baroque: Art in Genoa, 1600-1750 Sep 26, 2021–Jan 9, 2022

UPDATED: 8/11/2020 10:45:10 AM Exhibition Checklist: A Superb Baroque: Art in Genoa, 1600-1750 Sep 26, 2021–Jan 9, 2022 The exhibition is curated by Jonathan Bober, Andrew W. Mellon Senior Curator of Prints and Drawings National Gallery of Art; Piero Boccardo, superintendent of collections for the City of Genoa; and Franco Boggero, director of historic and artistic heritage at the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio, Genoa. The exhibition is organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and the Scuderie del Quirinale, Rome, with special cooperation from the City and Museums of Genoa. The exhibition is made possible by the Robert Lehman Foundation. Additional funding is provided by The Exhibition Circle of the National Gallery of Art. The exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Press Release: https://www.nga.gov/press/exh/5051.html Order Press Images: https://www.nga.gov/press/exh/5051/images.html Press Contact: Laurie Tylec, (202) 842-6355 or [email protected] Object ID: 5051-345 Valerio Castello David Offering the Head of Goliath to King Saul, 1640/1645 red chalk on laid paper overall: 28.6 x 25.8 cm (11 1/4 x 10 3/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection Object ID: 5051-315 Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione The Genius of Castiglione, before 1648 etching plate: 37 x 24.6 cm (14 9/16 x 9 11/16 in.) sheet: 37.3 x 25 cm (14 11/16 x 9 13/16 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Ruth B. -

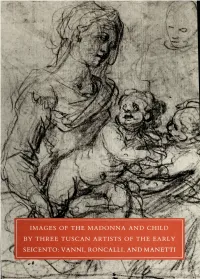

IMAGES of the MADONNA and CHILD by THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS of the EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, and MANETTI Digitized by Tine Internet Arcliive

r.^/'v/\/ f^jf ,:\J^<^^ 'Jftf IMAGES OF THE MADONNA AND CHILD BY THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS OF THE EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, AND MANETTI Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/innagesofmadonnacOObowd OCCASIONAL PAPERS III Images of the Madonna and Child by Three Tuscan Artists of the Early Seicento: Vanni, Roncalli, and Manetti SUSAN E. WEGNER BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART BRUNSWICK, MAINE Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 86-070511 ISBN 0-91660(>-10-4 Copyright © 1986 by the President and Trustees of Bowdoin College All rights reserved Designed by Stephen Harvard Printed by Meriden-Stinehour Press Meriden, Connecticut, and Lunenburg, Vermont , Foreword The Occasional Papers of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art began in 1972 as the reincarnation of the Bulletin, a quarterly published between 1960 and 1963 which in- cluded articles about objects in the museum's collections. The first issue ofthe Occasional Papers was "The Walker Art Building Murals" by Richard V. West, then director of the museum. A second issue, "The Bowdoin Sculpture of St. John Nepomuk" by Zdenka Volavka, appeared in 1975. In this issue, Susan E. Wegner, assistant professor of art history at Bowdoin, discusses three drawings from the museum's permanent collection, all by seventeenth- century Tuscan artists. Her analysis of the style, history, and content of these three sheets adds enormously to our understanding of their origins and their interconnec- tions. Professor Wegner has given very generously of her time and knowledge in the research, writing, and editing of this article. Special recognition must also go to Susan L. -

Preliminary Inventory to the David Coffin Papers, 1918-2003

Preliminary Inventory to the David Coffin Papers, 1918-2003 Collection includes: 11 boxes of notebooks; 3 boxes of offprints; 3 boxes of catalog cards; 7 boxes of negatives; 3 boxes of slides; 11 boxes of unprocessed materials, papers and photographs. The collection has not been processed and is only partially rehoused. Biographical note: David Coffin (1918-2003) was an American historian of Renaissance gardens and landscape architecture. Coffin taught at Princeton University from 1949-1988, serving as chair of the art and archaeology department from 1964-1970. In addition, Coffin was the first chairman of the Garden Advisory Committee for Dumbarton Oaks, which led to the establishment of a scholarly program for garden and landscape studies in 1971. Coffin also organized the first garden symposium at Dumbarton Oaks in 1971, which focused on his métier, Italian gardens. Scope and Content: The collection consists of Coffin's personal papers and materials relating to his teaching career at Princeton University and his scholarly research interests in Renaissance architecture and garden history. Materials include notebooks, index cards, correspondence, typescripts, course syllabi, class and lecture notes, and offprints. Of particular note are Coffin's notebooks, which contain extensive research notes on English, French, and Italian gardens. There is also a significant amount of visual material, including photographs, slides, microfilm, and negatives. Inventory of Notebook Boxes: Box #1: Notebooks #1 – 13 + one unidentified Notebook #1 (brown): -

Our Lady of Mercy

doors Our Lady with the Child ceramic bas-relief of Saint Jesus (in the centre) and musi- Maria Giuseppa Rossello 3 , cal angels. foundress of the Daughters of Our Lady of Mercy. The third chapel e Shrine hosts a masterpiece by Built in the same year as the Domenichino (Domenico Apparition (1536) following a Zampieri; 1581 - 1641), the design by the architect Antonio Presentation of Mary in the Sormano Pace, the works lasted Temple 4 , a classical work until 1540. The interior of the of the Bolognese school. building with three naves, a On the left wall is a bust crypt and a very raised pres- of Saint Giuseppe Marello bytery is in Lombard medieval 3 canonized in 2005. style, perhaps as a sign of ven- The fourth chapel con- eration for the old cathedral of school. Behind the altar is tains a Crucifi xion 5 by G.B. Savona, which in those years was a magnifi cent wooden choir Paggi (1554 - 1627) from destined to be demolished by 1 with two orders of stalls the Genoese school. the Genoese Republic. In fact to carved by P. Grassi in the year The first chapel on a large extent the Shrine mirrors 2 1644 (his are also the cup- 5 the left as you enter the 7 the shape, size and elevation of boards in the sacristy which Shrine is dedicated to the this Cathedral. Apparition of 18th March 1536. date to 1643) and inlaid in The apse above the organ has Annunciation 6 . The can- artist from Genoa, and it is The crypt is reached through a This is where Pope Pius VII, the nineteenth century by the frescoes of musical angels by Eso vas is attributed to Andrea the oldest work present in the beautiful marble porch sculpted at the end of his imprisonment Savona family of Garassino. -

SS History.Pages

History Sancta Sanctorum The chapel now known as the Sancta Sanctorum was the original private papal chapel of the mediaeval Lateran Palace, and as such was the predecessor of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City. The popes made the Lateran their residence in the early 4th century as soon as the emperor Constantine had built the basilica, but the first reference to a private palace chapel dedicated to St Lawrence is in the entry in the Liber Pontificalis for Pope Stephen III (768-72). Pope Gregory IV (827-44) is recorded as having refitted the papal apartment next to the chapel. The entry for Pope Leo III (795-816) shows the chapel becoming a major store of relics. It describes a chest of cypress wood (arca cypressina) being kept here, containing "many precious relics" used in liturgical processions. The famous full-length icon of Christ Santissimo Salvatore acheropita was one of the treasures, first mentioned in the reign of Pope Stephen II (752-7) but probably executed in the 5th century. The name acheropita is from the Greek acheiropoieta, meaning "made without hands" because its legend alleges that St Luke began painting it and an angel finished it for him. The name of the chapel became the Sancta Sanctorum in the early 13th century because of these relics. Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) provided bronze reliquaries for the heads of SS Peter and Paul which were kept here then (they are now in the basilica), and also a silver-gilt covering for the Acheropita icon. The next pope, Honorius III, executed a major restoration of the chapel.