A Comparative Study with the Opet Festival- Masashi FUK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Ancient Egypt

THE ROLE OF THE CHANTRESS ($MW IN ANCIENT EGYPT SUZANNE LYNN ONSTINE A thesis submined in confonnity with the requirements for the degm of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civiliations University of Toronto %) Copyright by Suzanne Lynn Onstine (200 1) . ~bsPdhorbasgmadr~ exclusive liceacc aiiowhg the ' Nationai hiof hada to reproduce, loan, distnia sdl copies of this thesis in miaof#m, pspa or elccmnic f-. L'atm criucrve la propri&C du droit d'autear qui protcge cette thtse. Ni la thèse Y des extraits substrrntiets deceMne&iveatetreimprimCs ouraitnmcrtrepoduitssanssoai aut&ntiom The Role of the Chmaes (fm~in Ancient Emt A doctorai dissertacion by Suzanne Lynn On*, submitted to the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 200 1. The specitic nanire of the tiUe Wytor "cimûes", which occurrPd fcom the Middle Kingdom onwatd is imsiigated thrwgh the use of a dalabase cataloging 861 woinen whheld the title. Sorting the &ta based on a variety of delails has yielded pattern regatding their cbnological and demographical distribution. The changes in rhe social status and numbers of wbmen wbo bore the Weindicale that the Egyptians perceivecl the role and ams of the titk âiffefcntiy thugh tirne. Infomiation an the tities of ihe chantressw' family memkrs bas ailowed the author to make iderences cawming llse social status of the mmen who heu the title "chanms". MiMid Kingdom tifle-holders wverc of modest backgrounds and were quite rare. Eighteenth DMasty women were of the highest ranking families. The number of wamen who held the titk was also comparatively smaii, Nimeenth Dynasty women came [rom more modesi backgrounds and were more nwnennis. -

International Selection Panel Traveler's Guide

INTERNATIONAL SELECTION PANEL MARCH 13-15, 2019 TRAVELER’S GUIDE You are coming to EGYPT, and we are looking forward to hosting you in our country. We partnered up with Excel Travel Agency to give you special packages if you wish to travel around Egypt, or do a day tour of Cairo and Alexandria, before or after the ISP. The following packages are only suggested itineraries and are not limited to the dates and places included herein. You can tailor a trip with Excel Travel by contacting them directly (contact information on the last page). A designated contact person at the company for Endeavor guests has been already assigned to make your stay more special. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS: The Destinations • Egypt • Cairo • Journey of The Pharaohs: Luxor & Aswan • Red Sea Authentic Escape: Hurghada, Sahl Hasheesh and Sharm El Sheikh Must-See Spots in: Cairo, Alexandria, Luxor, Aswan & Sharm El Sheikh Proposed One-Day Excursions Recommended Trips • Nile Cruise • Sahl Hasheesh • Sharm El Sheikh Services in Cairo • Meet & Assist, Lounges & Visa • Airport Transfer Contact Details THE DESTINATIONS EGYPT Egypt, the incredible and diverse country, has one of a few age-old civilizations and is the home of two of the ancient wonders of the world. The Ancient Egyptian civilization developed along the Nile River more than 7000 years ago. It is recognizable for its temples, hieroglyphs, mummies, and above all, the Pyramids. Apart from visiting and seeing the ancient temples and artefacts of ancient Egypt, there is also a lot to see in each city. Each city in Egypt has its own charm and its own history, culture, activities. -

Teacher's Guide for Calliope

Teacher’s Guide for Calliope Majestic Karnak, Egypt’s Home of the Gods September 2009 Teacher’s Guide prepared by: Nancy Attebury, B.S. Elementary Ed., M.A. Children’s Literature. She is a children’s author from Oregon. In the Beginning pg. 4 (Drawing conclusions) Use pgs. 3 and 4 and the facts below to get answers. FACT: Karnak structures are north of Luxor today, but were inside the city of Thebes long ago. QUESTION 1: How would the area of Thebes compare in size to the city of Luxor? FACT: Karnak was the site of local festivals. QUESTION 2: What good would it do to have Karnak in the middle of Thebes instead of on the edge? FACT: King Montuhotep II, a 11th Dynasty king, conquered many centers of power. QUESTION 3: Why could Montuhotep II unify Egypt? FACT: Set and Horus poured “the waters of life” over the pharaoh Seti I. QUESTION 4: Why were the “waters of life” important to a ruler? Karnak Grows pg. 5 (Gathering information) Place Hatshepsut, Senwosret, Amenhotep III, Thurmose III, and Amenhotep I in the correct blanks. Ruler’s name What the ruler did Added a new temple to honor Mut, Amun’s wife. Added a building that became the Holy of Holies. It was called Akh-Menu Remodeled a temple that had been damaged by floodwaters. Made a temple four times larger than it was before. Destroyed the front of Senwosret’s old temple. A Beehive of Activity pg. 8 (Deducing) Use the article from p. 8 and the map plans on p. -

Patterns of Evidence: Exodus Lesson 1 – Timeline Watch First 20 Minutes

Patterns of Evidence: Exodus Lesson 1 – Timeline Watch first 20 minutes on Right Now media Exodus Story – Biblical Summary ◦ Joseph moved his family to Egypt during the 7-year famine ◦ Israelites lived in the land of Goshen ◦ Years after Joseph died, a new pharaoh became fearful of the large numbers of Israelites. ◦ Israelites became slaves ◦ Moses was 80 when God sent him to Egypt to free the Israelites ◦ After Passover, the Israelites wandered in the desert for 40 years ◦ Israelites conquered the Promised Land An Overview of Egyptian History Problems with Egyptian History ◦ Historians began with multiple lists of Pharaoh’s names carved on temple walls ◦ These lists are incomplete, sometimes skipping Pharaohs ◦ Once a “standard” list had been made, then they looked at other known histories and inserted the list ◦ These dates then became the accepted timeline Evidence for the Late Date – 1250 BC • Genesis 47:11-12 • Exodus 18-14 • Earliest archaeological recording of the Israelites dates to 1210 BC on the Merneptah Stele o Must be before that time o Merneptah was the son of Ramses II • Ten Commandments and Prince of Egypt Movies take the Late Date with Ramses II Evidence for the Early Date – 1440 BC • “From Abraham to Paul: A Biblical Chronology” by Andrew Steinmann • 1 Kings 6:1 – Solomon began building temple 480 years after the Exodus o Solomon’s reign began 971 BC and began building temple in 967 BC o Puts Exodus date at 1447 BC • 1 Chronicles 6 lists 19 generations from Exodus to Solomon o Assume 25 years per generation – Exodus occurred -

Nilotic Livestock Transport in Ancient Egypt

NILOTIC LIVESTOCK TRANSPORT IN ANCIENT EGYPT A Thesis by MEGAN CHRISTINE HAGSETH Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Chair of Committee, Shelley Wachsmann Committee Members, Deborah Carlson Kevin Glowacki Head of Department, Cynthia Werner December 2015 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2015 Megan Christine Hagseth ABSTRACT Cattle in ancient Egypt were a measure of wealth and prestige, and as such figured prominently in tomb art, inscriptions, and even literature. Elite titles and roles such as “Overseer of Cattle” were granted to high ranking officials or nobility during the New Kingdom, and large numbers of cattle were collected as tribute throughout the Pharaonic period. The movement of these animals along the Nile, whether for secular or sacred reasons, required the development of specialized vessels. The cattle ferries of ancient Egypt provide a unique opportunity to understand facets of the Egyptian maritime community. A comparison of cattle barges with other Egyptian ship types from these same periods leads to a better understand how these vessels fit into the larger maritime paradigm, and also serves to test the plausibility of aspects such as vessel size and design, composition of crew, and lading strategies. Examples of cargo vessels similar to the cattle barge have been found and excavated, such as ships from Thonis-Heracleion, Ayn Sukhna, Alexandria, and Mersa/Wadi Gawasis. This type of cross analysis allows for the tentative reconstruction of a vessel type which has not been identified previously in the archaeological record. -

On the Orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

On the orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. On the orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor. Philica, Philica, 2018. hal-01700520 HAL Id: hal-01700520 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01700520 Submitted on 4 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. On the orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor Amelia Carolina Sparavigna (Department of Applied Science and Technology, Politecnico di Torino) Abstract The Avenue of Sphinxes is a 2.8 kilometres long Avenue linking Luxor and Karnak temples. This avenue was the processional road of the Opet Festival from the Karnak temple to the Luxor temple and the Nile. For this Avenue, some astronomical orientations had been proposed. After the examination of them, we consider also an orientation according to a geometrical planning of the site, where the Avenue is the diagonal of a square, a sort of best-fit straight line in a landscape constrained by the presence of temples, precincts and other processional avenues. The direction of the rising of Vega was probably used as reference direction for the surveying. -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'archéologie Orientale

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE BULLETIN DE L’INSTITUT FRANÇAIS D’ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne BIFAO 117 (2017), p. 9-27 Omar Abou Zaid A New Discovery of Catacomb in Qurnet Murai at Thebes Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 A New Discovery of Catacomb in Qurnet Murai at Thebes omar abou zaid* introduction The New Theban Tombs Mapping Project (NTTMP)1 intends to contribute to the ar- chaeological and topographical exploration of the Theban necropolis and to understand its layout as a World Heritage Site. -

255 Memnon, His Ancient Visitors and Some

255 MEMNON, HIS ANCIENT VISITORS AND SOME RELATED PROBLEMS Adam Łukaszewicz Memnon is known from ancient Greek sources as a king of Ethiopia.1 e notion of Ethiopia in Greek literature is very large and sometimes includes also the ebaid. In Egypt the name of Memnon is notori- ously associated with two famous colossal statues of Amenhotep III of the 18th Dynasty in Western ebes which once stood in front of an enormous temple, now almost completely vanished. At present, the temple is object of German excavations and many elements of it re- emerge on the site. e name of Memnon is a Greek misinterpretation of an Egyptian royal epithet. e Ramesside epithet Mery Amun pronounced approx- imately Meamun produced the Greek distortion into Memnon. Strabo states that the other name of Memnon is Ἰσµάνδης. at agrees with the names of a king called Usermaatre (Ἰσµάνδης) Meryamun (Μέµνων).2 e original Memnon was not Amenhotep III. Only the proximity of the colossi of Amenhotep III to the Memnonium of Ramesses II (Ramesseum), the Memnonium of Ramesses III (Medinet Habu) and to the western eban area called Memnoneia a£er these temples, encouraged the interpretation of the colossi of Amenhotep as statues of Memnon. e name of Memnoneia concerned particularly the area of Djeme,3 with the temple and palace complex of Medinet Habu built by Ramesses III. In the Later Roman period the temple precinct of 1 For the idea of two Memnons, the Trojan and the Ethiopian, Philostratus, Her. 3, 4. An extensive discussion of Memnon can be found in Letronne 1833; cf. -

Chicago House Bulletin IV, No.2

oi.uchicago.edu CHICAGO HOUSE Volume IV, No.2 BULLETIN AprilJO, 1993 Privately circulated Issued by The Epigraphic Survey of The Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago THE CHANGING FACE OF CURRENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL CHICAGO HOUSE WORK IN LUXOR: THE WEST BANK By Peter Dorman, Field Director By Ray Johnson, Senior Artist Chicago House (Concluded from the Winter Bulletin) April 4, 1993 Busy as the east bank seems, the west bank is even busier Dear Friends, these days. With the end of another season, the house seems eerily The director of the Canadian Institute in Cairo, Ted Brock, silent and a bit forlorn; the normal sounds of activity have and his wife, Lyla Pinch Brock, resumed their work in the begun to fade away as our artists, photographers, and Valley of the Kings in the tomb of Merneptah this month, where epigraphers leave for their homes in America and Europe. In they are cleaning and recording the fragments of an enormous Luxor the signs of spring, which we greet with such relief and shattered sarcophagus. Also in the Valley of the Kings, Drs. anticipation in Chicago after the hard freezes of winter, are Otto Schaden and Earl Ertman managed to gain entrance into instead harbingers of the end of our field work, and they the lower chambers of the poorly understood tomb of king presage the frenzy of last-minute work and harried packing. Amenmesse and recorded in photograph and in hand copy On our own compound, the bauhinia trees burst into small, some of the ruined wall paintings there. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology and the Book of Genesis

Answers Research Journal 4 (2011):127–159. www.answersingenesis.org/arj/v4/ancient-egyptian-chronology-genesis.pdf Ancient Egyptian Chronology and the Book of Genesis Matt McClellan, [email protected] Abstract One of the most popular topics among young earth creationists and apologists is the relationship of the Bible with Ancient Egyptian chronology. Whether it concerns who the pharaoh of the Exodus was, the background of Joseph, or the identity of Shishak, many Christians (and non-Christians) have wondered how these two topics fit together. This paper deals with the question, “How does ancient Egyptian chronology correlate with the book of Genesis?” In answering this question it begins with an analysis of every Egyptian dynasty starting with the 12th Dynasty (this is where David Down places Moses) and goes back all the way to the so called “Dynasty 0.” After all the data is presented, this paper will look at the different possibilities that can be constructed concerning how long each of these dynasties lasted and how they relate to the biblical dates of the Great Flood, the Tower of Babel, and the Patriarchs. Keywords: Egypt, pharaoh, Patriarchs, chronology, Abraham, Joseph Introduction Kingdom) need to be revised. This is important During the past century some scholars have when considering the relationship between Egyptian proposed new ways of dating the events of ancient history and the Tower of Babel. The traditional dating history before c. 700 BC.1 In 1991 a book entitled of Ancient Egyptian chronology places its earliest Centuries of Darkness by Peter James and four of dynasties before the biblical dates of the Flood and his colleagues shook the very foundations of ancient confusion of the languages at Babel. -

I General for Place Names See Also Maps and Their Keys

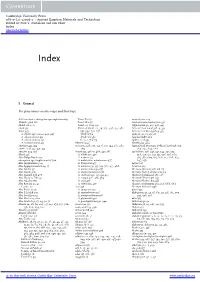

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12098-2 - Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology Edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw Index More information Index I General For place names see also maps and their keys. AAS see atomic absorption specrophotometry Tomb E21 52 aerenchyma 229 Abbad region 161 Tomb W2 315 Aeschynomene elaphroxylon 336 Abdel ‘AI, 1. 51 Tomb 113 A’09 332 Afghanistan 39, 435, 436, 443 abesh 591 Umm el-Qa’ab, 63, 79, 363, 496, 577, 582, African black wood 338–9, 339 Abies 445 591, 594, 631, 637 African iron wood 338–9, 339 A. cilicica 348, 431–2, 443, 447 Tomb Q 62 agate 15, 21, 25, 26, 27 A. cilicica cilicica 431 Tomb U-j 582 Agatharchides 162 A. cilicica isaurica 431 Cemetery U 79 agathic acid 453 A. nordmanniana 431 Abyssinia 46 Agathis 453, 464 abietane 445, 454 acacia 91, 148, 305, 335–6, 335, 344, 367, 487, Agricultural Museum, Dokki (Cairo) 558, 559, abietic acid 445, 450, 453 489 564, 632, 634, 666 abrasive 329, 356 Acacia 335, 476–7, 488, 491, 586 agriculture 228, 247, 341, 344, 391, 505, Abrak 148 A. albida 335, 477 506, 510, 515, 517, 521, 526, 528, 569, Abri-Delgo Reach 323 A. arabica 477 583, 584, 609, 615, 616, 617, 628, 637, absorption spectrophotometry 500 A. arabica var. adansoniana 477 647, 656 Abu (Elephantine) 323 A. farnesiana 477 agrimi 327 Abu Aggag formation 54, 55 A. nilotica 279, 335, 354, 367, 477, 488 A Group 323 Abu Ghalib 541 A. nilotica leiocarpa 477 Ahmose (Amarna oªcial) 115 Abu Gurob 410 A. -

Dates and Precursors of the Opet Festival

Dates and precursors of the Opet Festival 著者 Fukaya Masashi journal or 哲学・思想論叢 publication title number 33 page range 128(1)-100(29) year 2015-01-31 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2241/00126612 Dates and precursors of the Opet Festival Masashi FUKA Y A* Introduction The Festival of Opet was one of the most major religious celebrations in Egypt. It lasted as many as twenty-seven days in the middle of the inundation season under Ramses III in the Twentieth Dynasty (Table l). In this paper, I will first attempt to examine dates attested in various texts from the New Kingdom onwards, and their association with the cycles of the Nile and the moon. the latter of \vhich has not been explored in the context of this celebration. Secondly, its historical development from before the New Kingdom is explored in view that some earlier rituals foreshadowed the Opet Feast. Egyptian calendrical system was very complex, and thus detailed discussion on this subject is beyond the scope of this article.uJ However. it is useful to delineate the civil calendar, because it is relevant to the essential part of the present examination. Often wrongly designated 'the lunisolar calendar'. it was neither based on the lunar cycle nor the solar cycle in a strict sense. The year consisted of 365 days, divided into three seasons: Inundation Ub.t), Emergence (of crops: p1~t). and Harvest CS'mw). Each season was a group of four months of thirty days. To complement these 360 days, five days, which modern scholars call the epagomenal days, were added to the end of the year.