Apparel Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Asian Garments in Small Museums

AN ABSTRACTOF THE THESIS OF Alison E. Kondo for the degree ofMaster ofScience in Apparel Interiors, Housing and Merchandising presented on June 7, 2000. Title: Identification ofAsian Garments in Small Museums. Redacted for privacy Abstract approved: Elaine Pedersen The frequent misidentification ofAsian garments in small museum collections indicated the need for a garment identification system specifically for use in differentiating the various forms ofAsian clothing. The decision tree system proposed in this thesis is intended to provide an instrument to distinguish the clothing styles ofJapan, China, Korea, Tibet, and northern Nepal which are found most frequently in museum clothing collections. The first step ofthe decision tree uses the shape ofthe neckline to distinguish the garment's country oforigin. The second step ofthe decision tree uses the sleeve shape to determine factors such as the gender and marital status ofthe wearer, and the formality level ofthe garment. The decision tree instrument was tested with a sample population of 10 undergraduates representing volunteer docents and 4 graduate students representing curators ofa small museum. The subjects were asked to determine the country oforigin, the original wearer's gender and marital status, and the garment's formality and function, as appropriate. The test was successful in identifying the country oforigin ofall 12 Asian garments and had less successful results for the remaining variables. Copyright by Alison E. Kondo June 7, 2000 All rights Reserved Identification ofAsian Garments in Small Museums by Alison E. Kondo A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master ofScience Presented June 7, 2000 Commencement June 2001 Master of Science thesis ofAlison E. -

Fashion Designers' Decision-Making Process

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2013 Fashion designers' decision-making process: The influence of cultural values and personal experience in the creative design process Ja-Young Hwang Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Hwang, Ja-Young, "Fashion designers' decision-making process: The influence of cultural values and personal experience in the creative design process" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13638. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13638 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fashion designers’ decision-making process: The influence of cultural values and personal experience in the creative design process by Ja -Young Hwang A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Apparel, Merchandising, and Design Program of Study Committee: Mary Lynn Damhorst, Co-Major Professor Eulanda Sanders, Co-Major Professor Sara B. Marcketti Cindy Gould Barbara Caldwell Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2013 Copyright © Ja Young Hwang, 2013. All rights -

Traditional Clothing of East Asia That Speaks History

AJ1 ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT / LOS ANGELES TIMES FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 2021 |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| Tel: 213.487.0100 Asia Journal www.heraldk.com/en/ COVER STORY Traditional clothing of East Asia that speaks history A hanfu enthusiast walking out of the house in hanfu Trying on different styles of kimono during the Korea-Japan Festival in Seoul 2019 neckline from the robe. Since the yukata which is the summer ver- early 2000s, Hanfu has been get- sion of the kimono. Unlike tra- ting public recognition in China to ditional kimono, yukata is made revive the ancient tradition. Many from cotton or linen to escape the have modified the style to the mod- summer weather. While the people ern fashion trends to be worn daily of Japan only wear kimono during A woman in hanbok, posed in a traditional manner - Copyright to Photogra- A girl in habok, standing inside Gyeongbokgung Palace - Copyright to pher Studio Hongbanjang (Korea Tourism Organization) Photographer Pham Tuyen (Korea Tourism Organization) and like Hanbok, people have start- special occasions like weddings or ed to wear the clothes for big events tea ceremonies, it is very popular Kingdom (37 BCE - 668 CE). But made up of different materials such ture as well, showcased by many such as weddings. for tourists to rent or experience JENNY Hwang the hanbok we know today is the as gold, silver, and jade, depend- K-Pop idols such as BTS, Black- Kimono is the official national kimono. Asia Journal style established during the Cho- ing on social class. The royal fam- pink, and Mamamoo. dress of Japan. -

Epapyrus PDF Document

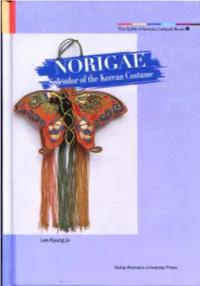

-The Spint or ""on-',,n Cultural Roots" Lee Kyung ja Ewha Womans University Press Norigae Splendor of the Korean Costume Lee KyungJa Translated by Lee Jea n Young Table of Contents CJ) '""d Foreword : A "Window" to Our Culture 5 .......ro ;:l 0.- ~ 0 I. What is Norigae? >-1 ~ History of Norignc 12 ~r1Q. l. 2. The Basic Form of Norigne 15 ~~ ~~ ll. The Composition of Norigae (6 l. Composition and Size 20 § 2. Materials 24 n 3. Crafting Techniques 26 0 C/l ill. The Symbolism of Norigae ~ 1. Shapes of Norignes 30 2. Charm Norignes 32 3. Wishing Norigncs 34 4. Norigncs for Eternal 36 Youth and Longevity 5. Noriglles for Practical Use 37 IV. Different types of Norigae l. Large Three-part Narigne 40 2. Three-part Norignc 46 3. Sil ver One-pa rt Norignc 60 4. White Jade One-part Norignc 63 5. Enameled One-part Norignc 66 6. Norignes to Wish fo r Sons 69 7. Ornamental Knife Norignc 72 8. Need le Case Norignc 76 9. Acupuncture Need le Case 79 (Cilill ltOllg) Norigac 10. Locust Leg(Bnllgndnri) Norigac 83 11. Perfume Case( Hynllg-gnp) Norigne 85 12. Perfume Bar Norignc 94 13. Tu rquoise Perfume Bead 98 Curtain Norignc 14. Embroidered Perfume 100 Pouch Nu rignc V. Norigaes and Customs 1. Wearing Norignc 11 0 2. Formal Rules 11 4 of Wearing Norignc 3. Norigne and the Seasons 116 4. Weddings. Funerals and Norigac ll9 VI. The Aesthetics of Norigae 1. The Aestheti cs of No rigllc 122 2. In Closing: Modern Hn ll bok 127 and the Norignc List of Pictures 132 I. -

2011 International Conference on Fashion Design and Apparel

2013 SFTI International Conference & The 18th International Invited Fashion Exhibition Proceeding July 07 - 15, 2013 Korean Cultural Center, Berlin, Germany Re-Union in Fashion The Society of Fashion and Textile Industry 2013 SFTI International Conference & The 18th International Invited Fashion Exhibition Proceeding “Re-Union in Fashion” July07-15, 2013 Korean Cultural Center, Berlin, Germany Organized by The Society of Fashion & Textile Industry (SFTI), Korea Korea Research Institute for Fashion Industry (KRIFI), Korea Eco Design Center, Dong-A University, Korea Sponsored by Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Korea Korean Cultural Center, Berlin, Germany German Fashion Industrie Foundation, Germany Willy Bogner GmbH & CO. KGaA Fashion Group Hyungji, Korea 1 Committee of 2013 SFTI International Conference and Exhibition President Yang Suk Ku (Kyungpook National Univ., Korea) Vice President EunJoo Park (Dong-A Univ., Korea) Sung Hye Jung (Inha Univ., Korea) Hye Kyung Kim (Wonkwang Univ., Korea) Chil Soon Kim (Kyung Hee Univ., Korea) Moon Young Kim (Keimyung Univ. Korea) Gilsoo Cho (YonseiUniv.,Korea) Byung Oh Choi (Fashion Group Hyungji Co.Ltd, Korea) Yong-Bin Jung (DaeguGyeongbukDesign Center, Korea) Choong-Hwan Kim (Korea Research Institute for Fashion Industry, Korea) Sangbae Yoon (Shinpung Textile Co.Ltd, Korea) Conference Chair Jin Hwa Lee (Pusan National Univ., Korea) Exhibition Chair Sung Hye Jung (Inha Univ., Korea) Field Trip Chair Hye Kyung Kim (Wonkwang Univ., Korea) Program Committee Chil Soon Kim (Kyung Hee Univ., Korea) DaeGeun Jeon (Andong Univ., Korea) Eun A Yeoh(Keimyung Univ., Korea) Eun Jung Kim(Mongolia International Univ., Mongolia) Eunjoo Cho (Honam Univ., Korea) Ho Jung Choo(Seoul National Univ., Korea) Hsueh Chin Ko(National Pingtung Univ. -

Study on the Recent Status of Rental Hanbok Jeogori for Women 111 Increased Their Numbers to 955 Hanbok Rental Sites Which Domestic and Foreign Tourists

Journal of Fashion Business Vol.22, No.3 Study on the Recent Status of — ISSN 1229-3350(Print) Rental Hanbok Jeogori for Women ISSN 2288-1867(Online) — J. fash. bus. Vol. 22, † No. 3:109-121, July. 2018 Sanghee Park https://doi.org/ 10.12940/jfb.2018.22.3.109 Dept. of Fashion Industry, Baewha Women's University, Korea Corresponding author — Sanghee Park Tel : +82-2-399-0759 Fax : +82-2-737-6722 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords Abstract rental jeogori, design, size, Recently, it is one of the popular fashion and cultural events that people of pattern the younger generation put on a hanbok and take a picture together with communicating by SNS. For this reason, the rent-hanbok market takes a big part of the Korean traditional costume market. Therefor, the recognition of hanbok is changed from the style of uncomfortable and ceremonial clothes, to becoming popular as everyday dress in the younger generation. The various designs of the rental hanbok show two different opinions. One is the increasing popular and general public interest and demand for wearing and showing off traditional hanbok fashions in a positive outlook. Another is the case of the wrong stereotype and knowledge for traditional costume which results in a negative outlook for this type of fashion statement. This study is to look into renting hanbok jeogori for women in Seoul and in Junju. There are 39 styles available in joegori. That being noted, the traditional jeogori has seop and git with dongjung. But it is seen that rental jeogoris do not have the seop, or have the dongjung position as similar to the Po as seen on the men’s coat. -

Hanbok, Our Beloved

Special hanbok How to get to exhibition Cheongwadae Around the Sarangchae exhibition space Hanbok, Our Subway ⑨ ⑦ ⑥ From Gyeongbokgung Station, Line 3, Exit No.4, turn around and head ⑤ Beloved ⑪ ⑧ towards the elevator. Walk about 800 meters and you will find Cheongwadae ⑫ ⑩ ④ Sarangchae in front of Cheongwadae fountain. ② ③ ① ⑬ Bus From bus stop Hankook Ilbo, 20 minutes on foot (1.4km) 1500, 272, 406, 708, 8272, 7022, 7025, 8710 ⑮ ⑭ ⑯ From bus stop Gyeongbokgung, 15 minutes on foot (1km) 171, 272, 708, 109, 601, 1020, 7025 From bus stop Hyoja-dong, 5 minutes on foot (350m) ① Exhibition Entrance 0212, 1020, 1711, 7016, 7018, 7022 ② Hanbok, Flows with the Time: 70 Years of Hanbok Looked Back upon with Photographs ③ Hanbok, Embraces the World: President Park Geun-hye’s Cultural Diplomacy ④ Hanbok, Recovers Light: Hanbok Worn by Rhee Syng-man, the First President, and First Train Special hanbok exhibition Lady Francesca Donner Rhee At Seoul Station Bus Transfer Center, near Exit No.9, take bus 1711 or 7016 celebrating the 70th anniversary of independence ⑤ It Is Called Nostalgia: Hanbok from the 1920s before Liberation and get off at bus stop Hyoja-dong. Walk for 5 minutes (350m). ⑥ Hanbok Fashion of the Stylish, Jeogori: Hanbok in 1950s-60s ⑦ Hanbok Fashion of the Stylish, Chima: Hanbok in 1950s-60s ⑧ Hanbok Fashion of the Stylish, Chima Jeogori: Hanbok in 1950s-60s hanbokcenter ⑨ Style Added to Class: Hanbok in 1950s-60s Tel: 02-739-4687, 02-739-0505, www.hanbokcenter.kr ⑩ The Golden Era of hanbok: Hanbok in 1970s-80s ⑪ Hanbok and the Korean Wave: Hanbok in Hallyu Dramas ⑫ Learn from the Past and Create New, Reinterpretation of Hanbok: Venue: Cheongwadae Sarangchae Hanbok in 1990s and on Cheongwadae Time: Sep. -

Perbandingan Songpa Sandaenori Dengan Yangju Byeolsandaenori

PERBANDINGAN SONGPA SANDAENORI DENGAN YANGJU BYEOLSANDAENORI HIKMAH MALIA NIM 153450200550013 PROGRAM STUDI BAHASA KOREA AKADEMI BAHASA ASING NASIONAL JAKARTA 2018 PERBANDINGAN SONGPA SANDAENORI DENGAN YANGJU BYEOLSANDAENORI Karya Tulis Akhir Ini Diajukan Untuk Melengkapi Pernyataan Kelulusan Program Diploma Tiga Akademi Bahasa Asing Nasional HIKMAH MALIA NIM 153450200550013 PROGRAM STUDI BAHASA KOREA AKADEMI BAHASA ASING NASIONAL JAKARTA 2018 PERNYATAAN KEASLIAN TUGAS AKHIR Dengan ini saya, Nama : Hikmah Malia NIM : 153450200550013 Program Studi : Bahasa Korea Tahun Akademik : 2015/2016 Menyatakan dengan sesungguhnya bahwa Karya Tulis Akhir yang berjudul Perbandingan Songpa Sandaenori dengan Yangju Byeolsandaenori merupakan hasil karya penulis dan penulis tidak melakukan tindakan plagiarisme. Jika terdapat karya tulis milik orang lain, saya akan mencantumkan sumber dengan jelas. Atas pernyataan ini penulis bersedia menerima sanksi yang dijatuhkan kepada penulis, apabila dikemudian hari ditemukan adanya pelanggaran atas etika akademik dalam pembuatan karya tulis ini. Demikian surat pernyataan ini dibuat dengan sebenar-benarnya. Jakarta, Agustus 2018 Hikmah Malia ABSTRAK Hikmah Malia, “ Perbandingan Songpa Sandaenori dengan Yangju Byeolsandaenori”. Karya tulis akhir ini membahas tentang perbandingan yang terdapat pada Songpa Sanadenori dengan Yangju Byeolsandaenori dimana keduanya merupakan cabang dari Sandaenori. Sandaenori merupakan nama lain dari tari topeng yang dikenal luas dengan nama Talchum (탈춤). Terdapat perubahan pada jenis Sandaenori. -

ASIAN ART MUSEUM UNVEILS COUTURE KOREA First Major Exhibition of Korean Fashion in U.S

PRESS CONTACT: Zac T. Rose 415.581.3560 [email protected] ASIAN ART MUSEUM UNVEILS COUTURE KOREA First Major Exhibition of Korean Fashion in U.S. Showcases Traditional Styles Alongside Contemporary Designs, Highlighting Global Influence from Seoul to San Francisco San Francisco, October 5 — Couture Korea presents historic and contemporary fashion from Korea and beyond, exclusively at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco from November 3, 2017 to February 4, 2018. The result of a partnership between the Seoul-based Arumjigi Culture Keepers Foundation and the Asian Art Museum, this original exhibition introduces American audiences to the incomparable artistry and the living legacy of Korean dress. Couture Korea — whose title borrows from the French to convey Korea’s comparable tradition of exquisite, handcrafted tailoring — weaves together courtly costume from centuries past with the runways of today’s fashion capitals. The exhibition features more than 120 works, including a king’s ethereal robe, various 18th- century women’s ensembles and layers of silk undergarments, alongside contemporary clothing stitched from hardworking denim and even high-tech neoprene. Re-creations of Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) garments using handmade fabrics are juxtaposed with modern styles by celebrated Korean designers Jin Teok, Im Seonoc and Jung Misun as well as looks from Chanel’s Karl Lagerfeld that were inspired by Korean artistic traditions. “Couture Korea elegantly interlaces the traditions of the past with contemporary clothing design to illuminate the ways Koreans — and fashion aficionados around the world — express themselves and their cultural affiliations through dress today,” explains exhibition curator and King Yeongjo's outer robe (dopo), 2015. -

A Study on the Items and Shapes of Korean Shrouds

IJCC, Vol. 3 No. 2, 100 ~ 123(2000) 26 A Study on the Items and Shapes of Korean Shrouds Min-Yi Nam* and Myung-Sook Han *Instructor, Joong Bu University Professor, Dept, of Clothing and Textiles, Sang Myung University Abstract The purpose of this research was to understand changes in Korean shrouds and to enhance practical usage of them by examing the items and shapes of Korean shrouds classified into two categories, traditional and current. We first examined the history of shrouds and funeral ceremonies from the prehistoric age to the Chos 6n dynasty, and second, examined the items and shapes of traditional and current shrouds. As for the items, no big changes were recognized though there had been some changes in the way of using Keum(^), Po(袍L and Kwadu(裏月j). Overall, the items had became somewhat simplified. The traditional shapes of shrouds are relatively -well-maintained despite some changes in current shrouds Aksu, Yeom이'女慨 etc, which had been made easier to put on. Key words : traditional shrouds, current shrouds, the items of shrouds, the shapes of shrouds, funeral ceremonies. and generally shown in everyday life as well as I ・ Introduction in funeral rites. Therefore, 'death' is a mournful thing but at the same time a rite that makes us Since Koreans have believed in the idea of feel reverence for the next world. the next world from ancient times, in which The rite of washing the deceased and clothing death is regarded as a departure towards a new them in ceremonial costumes is a mode of world rather than an end, they have practiced living of all times and a part of Korean culture. -

Summer School Korean-American Children

홀 매eong뻐ek City , {장 • · The host organiz gement organization 윷 Pyeongtaek Ci ongtaek Cultural Center .59 3.A. ·Date · Location 1st : 31 Uuly] ∼ 3[Aug] Wootdali culture Village ‘ 2nd: 7lAug ∼ 10 [Aug] 컵 1 .s9 !nts 고 43.A. 니 l. ::>cnedules /l 니 Q $$m 1| Q 이 잉 미e ‘、/,,、] ] 2 낀 q 까 [ 미 m / D m어 e ] 」 3 口 2. Learning Class (1) Taekwondo Class (Korean T 「 aditional Ma 「 ti al A 「 ts) · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 4 (2) English Drama Class (Korean T 「 aditional Fai 「Y Tale) · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 6 (The Wenny Man and the Three Goblins, Heungbu And Nolbu) 口 3. Experience Korean Culture ( 1) National Museum of Korea 12 (2) Where did old people live? 13 (3) Rice and farming tools 15 (4) Weapon and Warriors · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 16 (5) The National Folk Museum of Ko 「 ea · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 17 (6) Korean fol k tale ‘ Heungbu and Nolbu’ . 18 (7) Ko 「 ean t 「 aditional game ” Y ut-no 「 i ” 19 口 4. Experiential learning of Korean Traditional Culture ( 1) Jinwi Hyanggyo · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 21 (2) Korean Traditional Clothes(Hanbok) · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 22 (3) k orean t 「 a ditional bow · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 25 (4) Making miniature Sotdae and Jangseung · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 27 (5) Rubbing Copi e s ” Takbon ” (Ko 「 ean custom painting) · · · · · · · · · · · -

White Hanbok As an Expression of Resistance in Modern Korea

[ Research Paper] EISSN 2234-0793 PISSN 1225-1151 Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles Vol. 39, No. 1 (2015) p.121~132 http://dx.doi.org/10.5850/JKSCT.2015.39.1.121 White Hanbok as an Expression of Resistance in Modern Korea † Bong-Ha Seo Dept. of Stylist, Yong-in Songdam College Received August 29, 2014; Revised September 28, 2014; Accepted October 20, 2014 Abstract All aspects of clothing, including color, are a visible form of expression that carries invisible value. The pur- pose of this work is to study the expression of resistance in the white Hanbok in modern culture, specifically after the 1980s. Koreans have traditionally revered white color and enjoyed wearing white clothes. In Korea, white represents simplicity, asceticism, sadness, resistance against corruption, and the pursuit of innocence. This paper looks at: (i) the universal and traditional values of the color white, (ii) the significance of traditional white Korean clothing, (iii) the resistance characteristics of white in traditional Korean clothes, and (iv) the aesthetic values of white Hanbok. The white Hanbok often connotes resistance when it is worn in modern Korea. It is worn in folk plays, worn by shamans as a shamanist costume, worn by protestors for anti-establi- shment movements, and worn by social activists or progressive politicians. The fact that the white Hanbok has lost its position as an everyday dress in South Korea (instead symbolizing resistance when it is worn) is an unusual phenomenon. It shows that the white Hanbok, as a type of costume, is being used as a strong means of expression, following a change in the value of traditional costumes as it take on an expressive function.