Fashion Designers' Decision-Making Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jackson: Choosing a Methodology: Philosophical Underpinning

JACKSON: CHOOSING A METHODOLOGY: PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERPINNING Choosing a Methodology: Philosophical Practitioner Research Underpinning In Higher Education Copyright © 2013 University of Cumbria Vol 7 (1) pages 49-62 Elizabeth Jackson University of Cumbria [email protected] Abstract As a university lecturer, I find that a frequent question raised by Masters students concerns the methodology chosen for research and the rationale required in dissertations. This paper unpicks some of the philosophical coherence that can inform choices to be made regarding methodology and a well-thought out rationale that can add to the rigour of a research project. It considers the conceptual framework for research including the ontological and epistemological perspectives that are pertinent in choosing a methodology and subsequently the methods to be used. The discussion is exemplified using a concrete example of a research project in order to contextualise theory within practice. Key words Ontology; epistemology; positionality; relationality; methodology; method. Introduction This paper arises from work with students writing Masters dissertations who frequently express confusion and doubt about how appropriate methodology is chosen for research. It will be argued here that consideration of philosophical underpinning can be crucial for both shaping research design and for explaining approaches taken in order to support credibility of research outcomes. It is beneficial, within the unique context of the research, for the researcher to carefully -

Applications of Systems Engineering to the Research, Design, And

Applications of Systems Engineering to the Research, Design, and Development of Wind Energy Systems K. Dykes and R. Meadows With contributions from: F. Felker, P. Graf, M. Hand, M. Lunacek, J. Michalakes, P. Moriarty, W. Musial, and P. Veers NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. Technical Report NREL/TP-5000-52616 December 2011 Contract No. DE -AC36-08GO28308 Applications of Systems Engineering to the Research, Design, and Development of Wind Energy Systems Authors: K. Dykes and R. Meadows With contributions from: F. Felker, P. Graf, M. Hand, M. Lunacek, J. Michalakes, P. Moriarty, W. Musial, and P. Veers Prepared under Task No. WE11.0341 NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. National Renewable Energy Laboratory Technical Report NREL/TP-5000-52616 1617 Cole Boulevard Golden, Colorado 80401 December 2011 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. -

D8 Fashion Show Letter

D8 4-H CLOTHING & TEXTILES EVENTS General Rules & Guidelines OVERVIEW The 4-H Fashion Show is designed to recognize 4-H members who have completed a Clothing and Textiles project. The following objectives are taught in the Clothing and Textiles project: knowledge of fibers and fabrics, wardrobe selection, clothing construction, comparison shopping, fashion interpretation, understanding of style, good grooming, poise in front of others, and personal presentation skills. PURPOSE The Fashion Show provides an opportunity for 4-H members to exhibit the skills learned in their project work. It also provides members an opportunity to increase their personal presentation skills. ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS 1. Membership. Participants must be 4-H members currently enrolled in a Texas 4-H and Youth Development county program and actively participating in the Clothing & Textiles project. 2. Age Divisions. Age divisions are determined by a participant’s grade as of August 31, 2015 as follows: Division Grades Junior 3*, 4, or 5 *Must be at least 8 years old Intermediate 6, 7, or 8 Senior 9, 10, 11, or 12* *Must not be older than 18 years old 3. Events. There are five (5) events conducted at the District Fashion Show: Fashion Show 3 age divisions (Junior, Intermediate, Senior) Natural Fiber Seniors only Fashion Storyboard 3 age divisions (Junior, Intermediate, Senior) Trashion Show 2 age groups (Junior, Intermediate/Senior) Duds to Dazzle 2 age divisions (Junior/Intermediate, Senior) 4. Number of Entries. Participants may enter a maximum of one division/category in each of the four (4) events. Fashion Show Buying or Construction Division Natural Fiber Cotton or Wool/Mohair/Alpaca Fashion Storyboard Accessory, Jewelry, Non-wearable, Pet Clothing, or Wearable Trashion Show There are not separate categories/divisions. -

Choosing a Mixed Methods Design

04-Creswell (Designing)-45025.qxd 5/16/2006 8:35 PM Page 58 CHAPTER 4 CHOOSING A MIXED METHODS DESIGN esearch designs are procedures for collecting, analyzing, interpreting, and reporting data in research studies. They represent different mod- R els for doing research, and these models have distinct names and procedures associated with them. Rigorous research designs are important because they guide the methods decisions that researchers must make dur- ing their studies and set the logic by which they make interpretations at the end of studies. Once a researcher has selected a mixed methods approach for a study, the next step is to decide on the specific design that best addresses the research problem. What designs are available, and how do researchers decide which one is appropriate for their studies? Mixed methods researchers need to be acquainted with the major types of mixed methods designs and the common variants among these designs. Important considerations when choosing designs are knowing the intent, the procedures, and the strengths and challenges associated with each design. Researchers also need to be familiar with the timing, weighting, and mixing decisions that are made in each of the different mixed methods designs. This chapter will address • The classifications of designs in the literature • The four major types of mixed methods designs, including their intent, key procedures, common variants, and inherent strengths and challenges 58 04-Creswell (Designing)-45025.qxd 5/16/2006 8:35 PM Page 59 Choosing a Mixed Methods Design–●–59 • Factors such as timing, weighting, and mixing, which influence the choice of an appropriate design CLASSIFICATIONS OF MIXED METHODS DESIGNS Researchers benefit from being familiar with the numerous classifications of mixed methods designs found in the literature. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Model Commodities: Gender and Value in Contemporary Couture

Model Commodities: Gender and Value in Contemporary Couture By Xiaoyu Elena Wang A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Wendy L. Brown, Chair Professor Shannon C. Stimson Professor Ramona Naddaff Professor Julia Q. Bryan-Wilson Spring 2015 Abstract Model Commodities: Gender and Value in Contemporary Couture by Xiaoyu Elena Wang Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Wendy L. Brown, Chair Every January and June, the most exclusive and influential sector of the global apparel industry stages a series of runway shows in the high fashion, or, couture capitals of New York, Milan, London and Paris. This dissertation explores the production of material goods and cultural ideals in contemporary couture, drawing on scholarly and anecdotal accounts of the business of couture clothes as well as the business of couture models to understand the disquieting success of marketing luxury goods through bodies that appear to signify both extreme wealth and extreme privation. This dissertation argues that the contemporary couture industry idealizes a mode of violence that is unique in couture’s history. The industry’s shift of emphasis toward the mass market in the late 20th-century entailed divestments in the integrity of garment production and modeling employment. Contemporary couture clothes and models are promoted as high-value objects, belying however a material impoverishment that can be read from the models’ physiques and miens. 1 Table of Contents I. The enigma of couture…………………………………………………………………………..1 1. -

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Weronika Gaudyn December 2018 STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART Weronika Gaudyn Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor School Director Mr. James Slowiak Mr. Neil Sapienza _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Ms. Lisa Lazar Linda Subich, Ph.D. _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Sandra Stansbery-Buckland, Ph.D. Chand Midha, Ph.D. _________________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT Due to a change in purpose and structure of haute couture shows in the 1970s, the vision of couture shows as performance art was born. Through investigation of the elements of performance art, as well as its functions and characteristics, this study intends to determine how modern haute couture fashion shows relate to performance art and can operate under the definition of performance art. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee––James Slowiak, Sandra Stansbery Buckland and Lisa Lazar for their time during the completion of this thesis. It is something that could not have been accomplished without your help. A special thank you to my loving family and friends for their constant support -

How Fashion Erased the Politics of Streetwear in 2017

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Capstones Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Fall 12-15-2017 Mask On: How Fashion Erased the Politics of Streetwear in 2017 Frances Sola-Santiago How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gj_etds/219 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Mask On: How Fashion Erased the Politics of Streetwear in 2017 By Frances Sola-Santiago Hip-hop culture dominated the fashion zeitgeist in 2017. From a Louis Vuitton and Supreme collaboration to Gucci’s support of Harlem designer Dapper Dan’s store reopening, the fashion industry welcomed Black culture into the highest echelons of high fashion. Rapper Cardi B became the darling of New York Fashion Week in September after being rejected by designers throughout most of her career. Marc Jacobs traded the runway for the street, staging a show that included bucket hats, oversized jackets, and loads of corduroy on a large number of models of color. But while the industry appeared to diversify by acknowledging the indomitable force of hip-hop culture, it truly didn’t. The politics of hip-hop and Black culture were left out of the conversation and the players behind-the-scenes remained a homogeneous mass of privileged white Westerners. Nearly every high fashion brand this year capitalized on streetwear— a style of clothing born out of hip-hop culture in marginalized neighborhoods of New York City and Los Angeles, and none recognized the historical, cultural, and political heritage that made streetwear a worldwide phenomenon, symbolizing power and cool. -

Theoretically Comparing Design Thinking to Design Methods for Large- Scale Infrastructure Systems

The Fifth International Conference on Design Creativity (ICDC2018) Bath, UK, January 31st – February 2nd 2018 THEORETICALLY COMPARING DESIGN THINKING TO DESIGN METHODS FOR LARGE- SCALE INFRASTRUCTURE SYSTEMS M.A. Guerra1 and T. Shealy1 1Civil Engineering, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, USA Abstract: Design of new and re-design of existing infrastructure systems will require creative ways of thinking in order to meet increasingly high demand for services. Both the theory and practice of design thinking helps to exploit opposing ideas for creativity, and also provides an approach to balance stakeholder needs, technical feasibility, and resource constraints. This study compares the intent and function of five current design strategies for infrastructure with the theory and practice of design thinking. The evidence suggests the function and purpose of the later phases of design thinking, prototyping and testing, are missing from current design strategies for infrastructure. This is a critical oversight in design because designers gain much needed information about the performance of the system amid user behaviour. Those who design infrastructure need to explore new ways to incorporate feedback mechanisms gained from prototyping and testing. The use of physical prototypes for infrastructure may not be feasible due to scale and complexity. Future research should explore the use of prototyping and testing, in particular, how virtual prototypes could substitute the experience of real world installments and how this influences design cognition among designers and stakeholders. Keywords: Design thinking, design of infrastructure systems 1. Introduction Infrastructure systems account for the vast majority of energy use and associated carbon emissions in the United States (US EPA, 2014). -

Traditional Clothing of East Asia That Speaks History

AJ1 ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT / LOS ANGELES TIMES FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 2021 |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| Tel: 213.487.0100 Asia Journal www.heraldk.com/en/ COVER STORY Traditional clothing of East Asia that speaks history A hanfu enthusiast walking out of the house in hanfu Trying on different styles of kimono during the Korea-Japan Festival in Seoul 2019 neckline from the robe. Since the yukata which is the summer ver- early 2000s, Hanfu has been get- sion of the kimono. Unlike tra- ting public recognition in China to ditional kimono, yukata is made revive the ancient tradition. Many from cotton or linen to escape the have modified the style to the mod- summer weather. While the people ern fashion trends to be worn daily of Japan only wear kimono during A woman in hanbok, posed in a traditional manner - Copyright to Photogra- A girl in habok, standing inside Gyeongbokgung Palace - Copyright to pher Studio Hongbanjang (Korea Tourism Organization) Photographer Pham Tuyen (Korea Tourism Organization) and like Hanbok, people have start- special occasions like weddings or ed to wear the clothes for big events tea ceremonies, it is very popular Kingdom (37 BCE - 668 CE). But made up of different materials such ture as well, showcased by many such as weddings. for tourists to rent or experience JENNY Hwang the hanbok we know today is the as gold, silver, and jade, depend- K-Pop idols such as BTS, Black- Kimono is the official national kimono. Asia Journal style established during the Cho- ing on social class. The royal fam- pink, and Mamamoo. dress of Japan. -

Epapyrus PDF Document

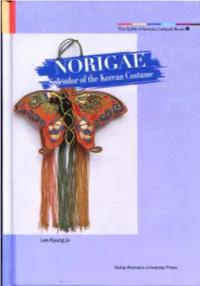

-The Spint or ""on-',,n Cultural Roots" Lee Kyung ja Ewha Womans University Press Norigae Splendor of the Korean Costume Lee KyungJa Translated by Lee Jea n Young Table of Contents CJ) '""d Foreword : A "Window" to Our Culture 5 .......ro ;:l 0.- ~ 0 I. What is Norigae? >-1 ~ History of Norignc 12 ~r1Q. l. 2. The Basic Form of Norigne 15 ~~ ~~ ll. The Composition of Norigae (6 l. Composition and Size 20 § 2. Materials 24 n 3. Crafting Techniques 26 0 C/l ill. The Symbolism of Norigae ~ 1. Shapes of Norignes 30 2. Charm Norignes 32 3. Wishing Norigncs 34 4. Norigncs for Eternal 36 Youth and Longevity 5. Noriglles for Practical Use 37 IV. Different types of Norigae l. Large Three-part Narigne 40 2. Three-part Norignc 46 3. Sil ver One-pa rt Norignc 60 4. White Jade One-part Norignc 63 5. Enameled One-part Norignc 66 6. Norignes to Wish fo r Sons 69 7. Ornamental Knife Norignc 72 8. Need le Case Norignc 76 9. Acupuncture Need le Case 79 (Cilill ltOllg) Norigac 10. Locust Leg(Bnllgndnri) Norigac 83 11. Perfume Case( Hynllg-gnp) Norigne 85 12. Perfume Bar Norignc 94 13. Tu rquoise Perfume Bead 98 Curtain Norignc 14. Embroidered Perfume 100 Pouch Nu rignc V. Norigaes and Customs 1. Wearing Norignc 11 0 2. Formal Rules 11 4 of Wearing Norignc 3. Norigne and the Seasons 116 4. Weddings. Funerals and Norigac ll9 VI. The Aesthetics of Norigae 1. The Aestheti cs of No rigllc 122 2. In Closing: Modern Hn ll bok 127 and the Norignc List of Pictures 132 I. -

Innovating a 90'S Streetwear Brand for Today's Fashion Industry

FOR US BY US: INNOVATING A 90'S STREETWEAR BRAND FOR TODAY'S FASHION INDUSTRY A Thesis submitted to the FAculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partiAl fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MAsters of Arts in CommunicAtion, Culture And Technology By Dominique HAywood, B.S WAshington, DC May 26, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Dominique HAywood All Rights Reserved ii FOR US BY US: INNOVATING A 90'S STREETWEAR BRAND FOR TODAY'S FASHION INDUSTRY Dominique HAywood, BS Thesis Advisor: J.R. Osborn, Ph.D ABSTRACT This thesis is a cAse study of how a vintAge fashion brand cAn be innovated through humAn centered design for the current fashion industry. IDEO, global design and innovation company, has clAssified humAn centered design as A method for identifying viAble, feAsible and desirable solutions with the integration of multidisciplinary insights (IDEO). For this thesis, the brand of focus is FUBU, for us by us, a 90’s era streetweAr brand that is a product of New York City hip-hop culture. A succinct proposAl for FUBU’s resurgence in the fashion industry will be designed by first identifying the viAbility of the fashion industry and feAsibility of the brand’s revival. ViAbility will be determined by detAiling the current stAte of the fashion and streetweAr industries. This is to estAblish the opportunities and threAts of new and returning entrants into the industry. FeAsibility will be declAred by reseArching the history and current stAte of the brand, its cultural relevancy, and its strengths and weAknesses.