Spindle Whorls from El Palmillo: Economic Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: a Macroregional Approach

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 24 Number 24 Spring 1991 Article 4 4-1-1991 New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: A Macroregional Approach Gary M. Feinman University of Wisconsin-Madison Linda M. Nicholas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Feinman, Gary M. and Nicholas, Linda M. (1991) "New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: A Macroregional Approach," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 24 : No. 24 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol24/iss24/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Feinman and Nicholas: New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: A Macroregi NEW PERSPECTIVES ON PREHISPANIC HIGHLAND MESOAMERICA: A MACROREGIONAL APPROACH1 GARY M. FEINMAN LINDA M. NICHOLAS Many social scientists might question the potential role for ar- chaeology in the study of world systems and macroregional politi- cal economies. After all, the principal contributions to this con- temporary research domain have come from history and other social sciences (e.g., Braudel 1972; Wallerstein 1974; Wolf 1982). In addition, most of the world systems literature to date has fo- cused on Europe and other regions of the Old World. This paper takes a somewhat novel tack, one that integrates contemporary findings in archaeology and history to expand and contribute to current debates concerning the nature of ancient world systems and interregional relations. Yet, the geographic focus is not Rome or Greece or even the area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, but rather prehispanic Mesoamerica, an area that encom- passes the southern two-thirds of what is now Mexico, as well as Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras, Costa Rica, and El Salvador. -

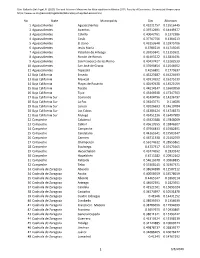

No. State Municipality Gini Atkinson 1 Aguascalientes Aguascalientes

Cite: Gallardo Del Angel, R. (2020) Gini and Atkinson Measures for Municipalities in Mexico 2015. Faculty of Economics. Universidad Veracruzana. https://www.uv.mx/personal/rogallardo/laboratory-of-applied-economics/ No. State Municipality Gini Atkinson 1Aguascalientes Aguascalientes 0.43221757 0.15516445 2Aguascalientes Asientos 0.39712691 0.14449377 3Aguascalientes Calvillo 0.40042761 0.1372586 4Aguascalientes Cosío 0.37767756 0.1304213 5Aguascalientes El Llano 0.43253648 0.15975706 6Aguascalientes Jesús María 0.3780219 0.11715045 7Aguascalientes Pabellón de Arteaga 0.39355841 0.13155921 8Aguascalientes Rincón de Romos 0.41403222 0.15831631 9Aguascalientes San Francisco de los Romo 0.40437427 0.15282539 10Aguascalientes San José de Gracia 0.37699854 0.12548952 11Aguascalientes Tepezalá 0.4256891 0.1779637 12Baja California Enseda 0.43223187 0.16224693 13Baja California Mexicali 0.43914592 0.16275139 14Baja California Playas de Rosarito 0.42097628 0.14521059 15Baja California Tecate 0.44214147 0.16600958 16Baja California Tijua 0.45446938 0.17347503 17Baja California Sur Comondú 0.41404796 0.14236797 18Baja California Sur La Paz 0.36343771 0.114026 19Baja California Sur Loreto 0.42026693 0.14610784 20Baja California Sur Los Cabos 0.41386124 0.14718573 21Baja California Sur Mulegé 0.42451236 0.16497989 22Campeche Calakmul 0.45923388 0.17848009 23Campeche Calkiní 0.43610555 0.15846507 24Campeche Campeche 0.47966433 0.19382891 25Campeche Candelaria 0.44265541 0.17503347 26Campeche Carmen 0.46711338 0.21462959 27Campeche Champotón 0.56174612 -

Movilidad Y Desarrollo Regional En Oaxaca

ISSN 0188-7297 Certificado en ISO 9001:2000‡ “IMT, 20 años generando conocimientos y tecnologías para el desarrollo del transporte en México” MOVILIDAD Y DESARROLLO REGIONAL EN OAXACA VOL1: REGIONALIZACIÓN Y ENCUESTA DE ORIGÉN Y DESTINO Salvador Hernández García Martha Lelis Zaragoza Manuel Alonso Gutiérrez Víctor Manuel Islas Rivera Guillermo Torres Vargas Publicación Técnica No 305 Sanfandila, Qro 2006 SECRETARIA DE COMUNICACIONES Y TRANSPORTES INSTITUTO MEXICANO DEL TRANSPORTE Movilidad y desarrollo regional en oaxaca. Vol 1: Regionalización y encuesta de origén y destino Publicación Técnica No 305 Sanfandila, Qro 2006 Esta investigación fue realizada en el Instituto Mexicano del Transporte por Salvador Hernández García, Víctor M. Islas Rivera y Guillermo Torres Vargas de la Coordinación de Economía de los Transportes y Desarrollo Regional, así como por Martha Lelis Zaragoza de la Coordinación de Ingeniería Estructural, Formación Posprofesional y Telemática. El trabajo de campo y su correspondiente informe fue conducido por el Ing. Manuel Alonso Gutiérrez del CIIDIR-IPN de Oaxaca. Índice Resumen III Abstract V Resumen ejecutivo VII 1 Introducción 1 2 Situación actual de Oaxaca 5 2.1 Situación socioeconómica 5 2.1.1 Localización geográfica 5 2.1.2 Organización política 6 2.1.3 Evolución económica y nivel de desarrollo 7 2.1.4 Distribución demográfica y pobreza en Oaxaca 15 2.2 Situación del transporte en Oaxaca 17 2.2.1 Infraestructura carretera 17 2.2.2 Ferrocarriles 21 2.2.3 Puertos 22 2.2.4 Aeropuertos 22 3 Regionalización del estado -

The Economy of Oaxaca Decomposed

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2015 The conomE y of Oaxaca Decomposed Albert Codina Sala Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Growth and Development Commons, Income Distribution Commons, International Economics Commons, Macroeconomics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Codina Sala, Albert, "The cE onomy of Oaxaca Decomposed" (2015). University Honors Program Theses. 89. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/89 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Economy of Oaxaca Decomposed An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in Department of Finance and Economics. By Albert Codina Sala Under the mentorship of Dr. Gregory Brock ABSTRACT We analyze the internal economy of Oaxaca State in southern Mexico across regions, districts and municipalities from 1999 to 2009. Using the concept of economic convergence, we find mixed evidence for poorer areas catching up with richer areas during a single decade of economic growth. Indeed, some poorer regions thanks to negative growth have actually diverged away from wealthier areas. Keywords: Oaxaca, Mexico, Beta Convergence, Sigma Convergence Thesis Mentor: _____________________ Dr. Gregory Brock Honors Director: _____________________ Dr. Steven Engel April 2015 College of Business Administration University Honors Program Georgia Southern University Acknowledgements The first person I would like to thank is my research mentor Dr. -

Fuzzy Modeling of Migration from the State of Oaxaca, Mexico

Fuzzy Modeling of Migration from the State of Oaxaca, Mexico Anais Vermonden and Carlos Gay Programa de Investigación en Cambio Climático, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, CU, Mexico Keywords: Fuzzy Logic, Migration, Oaxaca, Mexico, ANFIS. Abstract: This study shows an important innovation with the use of fuzzy logic to develop models on the migration factors occurring in the state of Oaxaca, México, since fuzzy logic has not been applied in this field. Migration is a complex system as individuals make their own decision to migrate. The major factors causing migration are: higher employment in the primary sector, high grades of unemployment, high marginalization index, small communities, soil degradation, violence and remittance received. Another tendency shown in these models is that municipalities in Oaxaca with greater levels of education are having higher migration levels due to the lack of opportunities to continue studies or well-paid jobs. Climate change may impose greater movement of people as it can worsen the already precarious soil situation. Even if the models present some error in the calculation of the migration index, it made clear what other variables should be included to show the impacts of climate change on migration. 1 INTRODUCTION 2013). There are a number of causes for the migration Oaxaca is located in southwest Mexico; it is divided from Oaxaca, and some of the most significant are into 570 municipalities. Oaxaca is one of the poorest lack of economic development, need for states with 61.9% of the population living under the diversification of income (remittance), ecological poverty line and, has one of the highest rates of rural deterioration, lack of educational opportunities, migration. -

The Field Museum 2011 Annual Report to the Board of Trustees

THE FIELD MUSEUM 2011 ANNUAL REPORT TO THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES COLLECTIONS AND RESEARCH Office of Collections and Research, The Field Museum 1400 South Lake Shore Drive Chicago, IL 60605-2496 USA Phone (312) 665-7811 Fax (312) 665-7806 http://www.fieldmuseum.org - This Report Printed on Recycled Paper - 1 CONTENTS 2011 Annual Report ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Collections and Research Committee of the Board of Trustees ................................................................. 8 Encyclopedia of Life Committee and Repatriation Committee of the Board of Trustees ............................ 9 Staff List ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 Publications ................................................................................................................................................. 15 Active Grants .............................................................................................................................................. 39 Conferences, Symposia, Workshops and Invited Lectures ........................................................................ 56 Museum and Public Service ...................................................................................................................... 64 Fieldwork and Research Travel ............................................................................................................... -

OECD Territorial Grids

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES DES POLITIQUES MEILLEURES POUR UNE VIE MEILLEURE OECD Territorial grids August 2021 OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities Contact: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Territorial level classification ...................................................................................................................... 3 Map sources ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Map symbols ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Disclaimers .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Australia / Australie ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Austria / Autriche ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium / Belgique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ...................................................................................................................................................... -

A Geochemical Study of Four Prehistoric Quarries in Oaxaca, Mexico

A GEOCHEMICAL STUDY OF FOUR PREHISTORIC QUARRIES IN OAXACA, MEXICO. by MICHELLE L. TROGDON (Under the direction of Ervan Garrison) ABSTRACT Petrographic and geochemical analyses of chert quarries used in antiquity for stone tool production in the Mixteca Alta, Oaxaca, Mexico have shown some promising results. This study combines petrography, electron microprobe analysis, hydrofluoric acid treatment, and isotope analysis to identify differences between four quarries and build a database of characteristics associated with each quarry. Major elements in trace amounts (Al, Ca, Na, Mg, and K) and their distribution, fossils, and δ18O values were unable to distinguish unique characteristics of the four quarries presented. However, these methods did reveal interesting information regarding chert formation in general and specific processes that influenced chert formation in Oaxaca. INDEX WORDS: Archaeological Geology, Oaxaca, Mixteca Alta, Chert, Electron Microprobe Analysis, Stable Isotopes. A GEOCHEMICAL STUDY OF FOUR PREHISTORIC QUARRIES IN OAXACA, MEXICO. by MICHELLE L. TROGDON B.S., Allegheny College, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2007 © 2007 MICHELLE L. TROGDON All Rights Reserved A GEOCHEMICAL STUDY OF FOUR PREHISTORIC QUARRIES IN OAXACA, MEXICO. by MICHELLE L. TROGDON Major Professor: Ervan Garrison Committee: Samuel E. Swanson Stephen A. Kowalewski Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2007 DEDICATION To my mother. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my wonderful committee at the University of Georgia; UGA, Watts- Wheeler, CLACS, SAAS; special thanks to INAH; Dr. Ronald Spores and Dr. -

Social Inequality at Monte Alban Oaxaca: Household Analysis from Terminal Formative to Early Classic

SOCIAL INEQUALITY AT MONTE ALBAN OAXACA: HOUSEHOLD ANALYSIS FROM TERMINAL FORMATIVE TO EARLY CLASSIC by Ernesto González Licón B.A. Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1982 M.A. Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía, 1984 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2003 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Ernesto González Licón It was defended on March 12, 2003 and approved by Dr. Olivier de Montmollin ________________________________ Dr. Marc Bermann ________________________________ Dr. Katheryn Linduff ________________________________ Dr. Robert D. Drennan ________________________________ Committee Chairperson ii Copyright by Ernesto González Licón 2003 iii SOCIAL INEQUALITY AT MONTE ALBAN OAXACA: HOUSEHOLD ANALYSIS FROM TERMINAL FORMATIVE TO EARLY CLASSIC Ernesto González Licón, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2003 The main objective of this dissertation is to reconstruct patterns of social organization and degrees of social stratification in Monte Albán, the capital of the ancient Zapotec state in what is now the state of Oaxaca, Mexico. Social stratification has been defined as the division of a society into categories of individuals organized into hierarchical segments based on access to strategic resources. The study of social stratification is an important aspect to research about the development of complex societies, since stratification has its origin in differential access to strategic resources, and, once the state arises as a form of government, this inequality is institutionalized, and social strata or social classes are formed. This research is based on archaeological data from 12 residential units distributed throughout three different parts of the city and attempts to clarify the composition of the social structure at Monte Albán. -

Feinman CV-3

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Gary M. Feinman ADDRESS: Department of Anthropology The Field Museum 1400 South Lake Shore Drive Chicago, IL 60605-2496 TELEPHONE: Office: (312) 665-7187 Fax: (312) 665-7193 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: February, 1980 Ph.D. granted by the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. December, 1972 B.A. with High Honors from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. RESEARCH INTERESTS: Archaeological Method and Theory Craft Specialization Mesoamerica The Development of Complex Societies Regional Analysis China Demography Ceramic Production Southwestern United States Human Ecology Households DISSERTATION TITLE: The Relationship Between Administrative Organization and Ceramic Production in the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico. Dissertation Chairman: Dr. Gregory A. Johnson, Hunter College, CUNY. PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS: 2003- Adjunct Full Professor, Northwestern University 1999- Adjunct Full Professor, University of Illinois at Chicago 1999- Curator, The Field Museum 1999-06 Chair, The Field Museum 1992-99 Full Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1986-92 Associate Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1983-86 Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1982-83 Assistant Professor, Bloomsburg State College 1980-82 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Arizona State University 1978-79 Visiting Instructor, Arizona State University 1976 Adjunct Lecturer, Lehman College, CUNY 1974-75 Instructor, Queens College, CUNY FIELD AND RESEARCH POSITIONS: 2009- Project Director, Excavation at the Mitla Fortress, Oaxaca, Mexico 2008- Co Principal Investigator, The Lanyatai-Qingdao Regional Survey in Southeastern Shandong Province, China (with Hui Fang). 1999-08 Project Director, Excavation at El Palmillo, Oaxaca, Mexico. 1995-07 Co-Principal Investigator, Systematic Regional Survey in Southeastern Shandong Province, China (with Anne P. -

NEWMODEL.Pdf

1 2 3 Universidad Tecnológica de la Mixteca Directorio Dr. Modesto Seara Vázquez Rector M.C. Gerardo García Hernández Vice-Rector Académico C.P. José Javier Ruiz Santiago Vice-Rector Administrativo Lic. María de los Ángeles Peralta Arias Vice-Rectora de Relaciones y Recursos 4 5 First Spanish edition, May 2009. ISBN: 978-607-95222-1-6 Second Spanish edition, March 2010. ISBN: 978-607-95222-1-6 This is an updated translation into English of the book “Un Nuevo Modelo de Universidad. Universidades para el Desa- rrollo”, first published by the Universidad Tecnológica de la Mixteca in 2009, with a Second updated Edition in 2010. Diseño:Eruvid Cortés Camacho D.R. 2010 Modesto Seara Vázquez Universidad Tecnológica de la Mixteca Carretera a Acatlima, Km. 2.5. Huajuapan de León, Oax. C.P. 69000 6 Preface In the following pages I offer my conceptions of what a university should be. They are ideas generated by a long academic life in vari- ous countries and continents. However, I spent the longest period of time in Mexico, in Mexico City and the last twenty years in the state of Oaxaca. My academic background in the field of international relations has forced me to always keep an eye in what is happening on the world stage. This has allowed me to incorporate knowledge and experiences to the university project that I have had the enor- mous privilege to develop. As is natural, not everyone will agree with my opinions regarding the idea of university; I would be disappointed if they did. However, I want to invoke three things in my support: one, these are not im- provised ideas, but the fruit of a wealth of experience in the field of universities to various degrees; two, I hope to have demonstrated with the facts that these ideas work and the possibility of combining theory and practise is something that not many university theorists have been able to do; three, I have expressed my ideas with the same freedom with which I have been applying them over the decades. -

Ucla Archaeology Field School

THE OAXACA-PACIFIC RIM INTERDISCIPLINARY PROJECT: CONTACT, COLONIALISM, AND RITUAL IN SOUTHERN MEXICO Course ID: ARCH 330A June 16-July 13, 2019 FIELD SCHOOL DIRECTOR: Dr. Aaron Sonnenschein, California State University Los Angeles ([email protected]) CO-DIRECTORS: Dr. Danny Zborover, Institute for Field Research ([email protected]) Dr. John M.D. Pohl, California State University Los Angeles & UCLA ([email protected]) INTRODUCTION The role of the Pacific Ocean is taking on increasing importance in Pre-Columbian, Colonial, and Contemporary studies of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Recent research in regions as diverse as Mesoamerica, Central America, Ecuador, and the American Southwest are identifying significant forms of mutual social and economic interactions that are entirely changing our understanding of cultural transformations across the Americas. Lustrous turquoise, gold, and exotic shells; colorful dyes and feathers; and delicious cacao beans were extensively produced and exchanged between these cultural areas. Our project focuses on a key region within this vast system— the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca and its adjacent Pacific Coast— a rugged geography further shaped by millennia of population movements over land and sea. Oaxaca is home to 16 distinct ethnolinguistic groups who speak over 200 dialects, the most ethnically complex and biologically diverse state in Mexico. Operating within these transnational sociocultural networks, for over two millennia Oaxacan indigenous cultures constructed monumental sites here; ruled over vast city-states; invented complex writing systems and iconography; and crafted among the finest artistic traditions in the world, some of which are still perpetuated to this day. The clash of the indigenous and the European worlds in the 16th century created a unique culture, the legacy of which underlies the modern nation of Mexico.