NEWMODEL.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Declining Use of Mixtec Among Oaxacan Migrants and Stay-At

UC San Diego Working Papers Title The Declining Use of the Mixtec Language Among Oaxacan Migrants and Stay-at-Homes: The Persistence of Memory, Discrimination, and Social Hierarchies of PowerThe Declining Use of the Mixtec Language Among Oaxacan Migrants and Stay-at-Homes: The Persis... Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/64p447tc Author Perry, Elizabeth Publication Date 2017-10-18 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Perry The Declining Use of the Mixtec Language 1 The Center for Comparative Immigration Studies CCIS University of California, San Diego The Declining Use of the Mixtec Language Among Oaxacan Migrants and Stay-at-Homes: The Persistence of Memory, Discrimination, and Social Hierarchies of Power Elizabeth Perry University of California, San Diego Working Paper 180 July 2009 Perry The Declining Use of the Mixtec Language 2 Abstract Drawing on binational ethnographic research regarding Mixtec “social memory” of language discrimination and Mixtec perspectives on recent efforts to preserve and revitalize indigenous language use, this study suggests that language discrimination, in both its overt and increasingly concealed forms, has significantly curtailed the use of the Mixtec language. For centuries, the Spanish and Spanish-speaking mestizo (mixed blood) elite oppressed the Mixtec People and their linguistic and cultural practices. These oppressive practices were experienced in Mixtec communities and surrounding urban areas, as well as in domestic and international migrant destinations. In the 1980s, a significant transition occurred in Mexico from indigenismo to a neoliberal multicultural framework. In this transition, discriminatory practices have become increasingly “symbolic,” referring to their assertion in everyday social practices rather than through overt force, obscuring both the perpetrator and the illegitimacy of resulting social hierarchies (Bourdieu, 1991). -

Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Season of 1997

2440 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 127 Eastern North Paci®c Hurricane Season of 1997 MILES B. LAWRENCE Tropical Prediction Center, National Weather Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Miami, Florida (Manuscript received 15 June 1998, in ®nal form 20 October 1998) ABSTRACT The hurricane season of the eastern North Paci®c basin is summarized and individual tropical cyclones are described. The number of tropical cyclones was near normal. Hurricane Pauline's rainfall ¯ooding killed more than 200 people in the Acapulco, Mexico, area. Linda became the strongest hurricane on record in this basin with 160-kt 1-min winds. 1. Introduction anomaly. Whitney and Hobgood (1997) show by strat- Tropical cyclone activity was near normal in the east- i®cation that there is little difference in the frequency of eastern Paci®c tropical cyclones during El NinÄo years ern North Paci®c basin (east of 1408W). Seventeen trop- ical cyclones reached at least tropical storm strength and during non-El NinÄo years. However, they did ®nd a relation between SSTs near tropical cyclones and the ($34 kt) (1 kt 5 1nmih21 5 1852/3600 or 0.514 444 maximum intensity attained by tropical cyclones. This ms21) and nine of these reached hurricane force ($64 kt). The long-term (1966±96) averages are 15.7 tropical suggests that the slightly above-normal SSTs near this storms and 8.7 hurricanes. Table 1 lists the names, dates, year's tracks contributed to the seven hurricanes reach- maximum 1-min surface wind speed, minimum central ing 100 kt or more. pressure, and deaths, if any, of the 1997 tropical storms In addition to the infrequent conventional surface, and hurricanes, and Figs. -

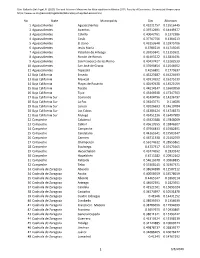

No. State Municipality Gini Atkinson 1 Aguascalientes Aguascalientes

Cite: Gallardo Del Angel, R. (2020) Gini and Atkinson Measures for Municipalities in Mexico 2015. Faculty of Economics. Universidad Veracruzana. https://www.uv.mx/personal/rogallardo/laboratory-of-applied-economics/ No. State Municipality Gini Atkinson 1Aguascalientes Aguascalientes 0.43221757 0.15516445 2Aguascalientes Asientos 0.39712691 0.14449377 3Aguascalientes Calvillo 0.40042761 0.1372586 4Aguascalientes Cosío 0.37767756 0.1304213 5Aguascalientes El Llano 0.43253648 0.15975706 6Aguascalientes Jesús María 0.3780219 0.11715045 7Aguascalientes Pabellón de Arteaga 0.39355841 0.13155921 8Aguascalientes Rincón de Romos 0.41403222 0.15831631 9Aguascalientes San Francisco de los Romo 0.40437427 0.15282539 10Aguascalientes San José de Gracia 0.37699854 0.12548952 11Aguascalientes Tepezalá 0.4256891 0.1779637 12Baja California Enseda 0.43223187 0.16224693 13Baja California Mexicali 0.43914592 0.16275139 14Baja California Playas de Rosarito 0.42097628 0.14521059 15Baja California Tecate 0.44214147 0.16600958 16Baja California Tijua 0.45446938 0.17347503 17Baja California Sur Comondú 0.41404796 0.14236797 18Baja California Sur La Paz 0.36343771 0.114026 19Baja California Sur Loreto 0.42026693 0.14610784 20Baja California Sur Los Cabos 0.41386124 0.14718573 21Baja California Sur Mulegé 0.42451236 0.16497989 22Campeche Calakmul 0.45923388 0.17848009 23Campeche Calkiní 0.43610555 0.15846507 24Campeche Campeche 0.47966433 0.19382891 25Campeche Candelaria 0.44265541 0.17503347 26Campeche Carmen 0.46711338 0.21462959 27Campeche Champotón 0.56174612 -

Programa Para El Desarrollo Del Istmo De Tehuantepec

Programa para el Desarrollo del Istmo de Tehuantepec CMIC Conferencia Binacional de Infraestructura 17 de junio de 2019 Antecedentes • El desarrollo del país no ha sido justo ni equitativo; se han incrementado las desigualdades entre regiones y grupos sociales • El desarrollo económico no propició el bienestar de las mayorías • El desarrollo debe incluirnos a todas y a todos; y mejorar las condiciones en que vivimos, en especial de los más desprotegidos • Es necesaria otra forma de generar el desarrollo de la economía y orientarla hacia una nueva manera de crecer y distribuir los resultados 2 El Istmo de Tehuantepec Es una región que crece Incluye 79 municipios: 33 mucho menos que otras y de Veracruz y 46 de tiene una población con Oaxaca graves carencias sociales, Es el punto de acceso a en comparación con otras la región a la región regiones del país Sur-Sureste, que comprende una cuarta parte de las entidades del país 3 Ventajas competitivas del Istmo de Tehuantepec Es un punto de cruce de flujos económicos de y hacia el Sur-Sureste del país Une dos océanos con una franja de 300 km; por lo que es estratégica para el mundo Tiene un gran posicionamiento en rutas mundiales de transporte marítimo Es un punto crítico de la ruta para el abasto de electricidad, petróleo y petrolíferos al centro y norte del país Tiene competitividad en el tránsito de mercancías: costo. distancia, tiempo de traslado Dispone de recursos naturales: agua, tierra, aire, costas, energéticos para sustentar el desarrollo El nuevo modelo de desarrollo en el Istmo debe: -

Hironymousm16499.Pdf

Copyright by Michael Owen Hironymous 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Michael Owen Hironymous certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Santa María Ixcatlan, Oaxaca: From Colonial Cacicazgo to Modern Municipio Committee: Julia E. Guernsey, Supervisor Frank K. Reilly, III, Co-Supervisor Brian M. Stross David S. Stuart John M. D. Pohl Santa María Ixcatlan, Oaxaca: From Colonial Cacicazgo to Modern Municipio by Michael Owen Hironymous, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2007 Dedication Al pueblo de Santa Maria Ixcatlan. Acknowledgements This dissertation project has benefited from the kind and generous assistance of many individuals. I would like to express my gratitude to the people of Santa María Ixcatlan for their warm reception and continued friendship. The families of Jovito Jímenez and Magdaleno Guzmán graciously welcomed me into their homes during my visits in the community and provided for my needs. I would also like to recognize Gonzalo Guzmán, Isabel Valdivia, and Gilberto Gil, who shared their memories and stories of years past. The successful completion of this dissertation is due to the encouragement and patience of those who served on my committee. I owe a debt of gratitude to Nancy Troike, who introduced me to Oaxaca, and Linda Schele, who allowed me to pursue my interests. I appreciate the financial support that was extended by the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies of the University of Texas and FAMSI. -

Climatology, Variability, and Return Periods of Tropical Cyclone Strikes in the Northeastern and Central Pacific Ab Sins Nicholas S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School March 2019 Climatology, Variability, and Return Periods of Tropical Cyclone Strikes in the Northeastern and Central Pacific aB sins Nicholas S. Grondin Louisiana State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Climate Commons, Meteorology Commons, and the Physical and Environmental Geography Commons Recommended Citation Grondin, Nicholas S., "Climatology, Variability, and Return Periods of Tropical Cyclone Strikes in the Northeastern and Central Pacific asinB s" (2019). LSU Master's Theses. 4864. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4864 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIMATOLOGY, VARIABILITY, AND RETURN PERIODS OF TROPICAL CYCLONE STRIKES IN THE NORTHEASTERN AND CENTRAL PACIFIC BASINS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Nicholas S. Grondin B.S. Meteorology, University of South Alabama, 2016 May 2019 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my family, especially mom, Mim and Pop, for their love and encouragement every step of the way. This thesis is dedicated to my friends and fraternity brothers, especially Dillon, Sarah, Clay, and Courtney, for their friendship and support. This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and college professors, especially Mrs. -

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Lamoreux, J. F., McKnight, M. W., and R. Cabrera Hernandez (2015). Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. xxiv + 320pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1717-3 DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2015.SSC-OP.53.en Cover photographs: Totontepec landscape; new Plectrohyla species, Ixalotriton niger, Concepción Pápalo, Thorius minutissimus, Craugastor pozo (panels, left to right) Back cover photograph: Collecting in Chamula, Chiapas Photo credits: The cover photographs were taken by the authors under grant agreements with the two main project funders: NGS and CEPF. -

ISTMO DE TEHUANTEPEC: DE LO REGIONAL a LA GLOBALIZACIÓN (O Apuntes Para Pensar Un Quehacer) *

ISTMO DE TEHUANTEPEC: DE LO REGIONAL A LA GLOBALIZACIÓN (o apuntes para pensar un quehacer) * Nemesio J. Rodríguez Programa Universitario México Nación Multicultural ________________________________________________________________________________ (*) Segunda edición electrónica. Una versión impresa fue publicada en 2003, con el mismo título, por la Secretaría de Asuntos Indígenas (SAI) del Gobierno del estado de Oaxaca. 2 INDICE INDICE.................................................................................................................................................................2 Prólogo ................................................................................................................................................................4 Introducción General .........................................................................................................................................13 El Istmo Revisitado o los Contextos de un Texto Añejo de 6 Años ..............................................................13 NOTAS:..........................................................................................................................................................20 1. PROGRAMA INTEGRAL DE DESARROLLO ECONÓMICO PARA EL ISTMO DE TEHUANTEPEC (OAXACA-VERACRUZ) ....................................................................................................................................37 1.1 PROPUESTA DE LA CONSULTORÍA MAESTRA.................................................................................37 -

El Istmo Veracruzano: Notas Para Una Historia De La Construcción De Una Región*

EL ISTMO VERACRUZANO: NOTAS PARA UNA HISTORIA DE LA CONSTRUCCIÓN DE UNA REGIÓN* MARTÍN AGUILAR SÁNCHEZ LEOPOLDO ALAFITA MÉNDEZ** Introducción En esta reunión nos interesa destacar las características económicas de la subregión veracruzana del Istmo de Tehuantepec, poniendo mayor énfasis en la zona Minátitlán-Coatzacoalcos y su área de in fluencia en los años que van de 1880 a 1911. Particularmente, nues tro interés en el periodo de esta región se justifica para entender el presente de una zona industrial estratégica para el país por su ubi cación espacial, por el papel de las rutas marítimas y fluviales, por el tipo de producción que se desencadena entre la etapa colonial y el siglo XIX; en fin, por su integración a través del ferrocarril y la pe netración a partir de la explotación petrolera. Nuestro interés en el pasado de esta región es válido sobre todo en tanto nos sirva para entender el presente de una zona industrial, clave para el conjunto del país. En este sentido se privilegian tres momentos en la conformación de la subregión Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán: * Este trabajo fue presentado por los autores, investigadores del Instituto de Investigaciones Histórico-Sociales de la UV, en el Seminario sobre el desarrollo del capitalismo, realizado en Gudulajara, Jal., México, en octubre de 1993. ** Realizado con la colaboración de Ricardo Corzo Ramírez, Instituto de Investigaciones Histórico-Sociales, UV, Xalapa, Ver., México. 67 1. El que se definió por la posición de las vías naturales de comuni cación que la condujo a una situación en la que se convierte en puente por su ubicación de cara al mar. -

DIAGNÓSTICO REGIONAL Región Costa

1 M4. Proyecto Piloto: Alfabetización con mujeres indígenas y afrodescendientes en el estado de Oaxaca Diagnóstico regional M4. Proyecto Piloto: Alfabetización con mujeres indígenas y afrodescendientes en el estado de Oaxaca DIAGNÓSTICO REGIONAL Región Costa Municipios Pinotepa de Don Luis San Juan Colorado Santiago Tapextla Coordinadora Áurea Marcela Ceja Albanés Diciembre 16, 2011 2 M4. Proyecto Piloto: Alfabetización con mujeres indígenas y afrodescendientes en el estado de Oaxaca Diagnóstico regional ÍNDICE Introducción I. Contexto regional Región costa Distrito de Jamiltepec II. Contexto local y diagnóstico situacional La población mixteca 1. Pinotepa de Don Luis a) Contexto local b) Situación de las mujeres en el municipio 2. San Juan Colorado a) Contexto local b) Situación de las mujeres en el municipio La población afrodescendiente 3. Santiago Tapextla a) Contexto local b) Situación de las mujeres en el municipio III. Propuesta de intervención IV. Conclusiones Referencias bibliográficas 3 M4. Proyecto Piloto: Alfabetización con mujeres indígenas y afrodescendientes en el estado de Oaxaca Diagnóstico regional Introducción Oaxaca ocupa el tercer lugar en analfabetismo a nivel nacional según el XIII Censo de Población y Vivienda, INEGI 20101. Casi 17 de cada 100 personas no saben leer y escribir. Al mismo tiempo, según el PNUD 20062, Oaxaca se encuentra en el lugar 31 de los 32 estados de la República mexicana en materia de desarrollo con respecto al género. Esto significa que el acceso a los derechos fundamentales de las mujeres, incluyendo el derecho a la educación, no está garantizado. También es importante mencionar que el 34% de la población del estado es indígena, y de cada 100 personas indígenas, aproximadamente 52 son mujeres3. -

Movilidad Y Desarrollo Regional En Oaxaca

ISSN 0188-7297 Certificado en ISO 9001:2000‡ “IMT, 20 años generando conocimientos y tecnologías para el desarrollo del transporte en México” MOVILIDAD Y DESARROLLO REGIONAL EN OAXACA VOL1: REGIONALIZACIÓN Y ENCUESTA DE ORIGÉN Y DESTINO Salvador Hernández García Martha Lelis Zaragoza Manuel Alonso Gutiérrez Víctor Manuel Islas Rivera Guillermo Torres Vargas Publicación Técnica No 305 Sanfandila, Qro 2006 SECRETARIA DE COMUNICACIONES Y TRANSPORTES INSTITUTO MEXICANO DEL TRANSPORTE Movilidad y desarrollo regional en oaxaca. Vol 1: Regionalización y encuesta de origén y destino Publicación Técnica No 305 Sanfandila, Qro 2006 Esta investigación fue realizada en el Instituto Mexicano del Transporte por Salvador Hernández García, Víctor M. Islas Rivera y Guillermo Torres Vargas de la Coordinación de Economía de los Transportes y Desarrollo Regional, así como por Martha Lelis Zaragoza de la Coordinación de Ingeniería Estructural, Formación Posprofesional y Telemática. El trabajo de campo y su correspondiente informe fue conducido por el Ing. Manuel Alonso Gutiérrez del CIIDIR-IPN de Oaxaca. Índice Resumen III Abstract V Resumen ejecutivo VII 1 Introducción 1 2 Situación actual de Oaxaca 5 2.1 Situación socioeconómica 5 2.1.1 Localización geográfica 5 2.1.2 Organización política 6 2.1.3 Evolución económica y nivel de desarrollo 7 2.1.4 Distribución demográfica y pobreza en Oaxaca 15 2.2 Situación del transporte en Oaxaca 17 2.2.1 Infraestructura carretera 17 2.2.2 Ferrocarriles 21 2.2.3 Puertos 22 2.2.4 Aeropuertos 22 3 Regionalización del estado -

The Economy of Oaxaca Decomposed

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2015 The conomE y of Oaxaca Decomposed Albert Codina Sala Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Growth and Development Commons, Income Distribution Commons, International Economics Commons, Macroeconomics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Codina Sala, Albert, "The cE onomy of Oaxaca Decomposed" (2015). University Honors Program Theses. 89. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/89 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Economy of Oaxaca Decomposed An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in Department of Finance and Economics. By Albert Codina Sala Under the mentorship of Dr. Gregory Brock ABSTRACT We analyze the internal economy of Oaxaca State in southern Mexico across regions, districts and municipalities from 1999 to 2009. Using the concept of economic convergence, we find mixed evidence for poorer areas catching up with richer areas during a single decade of economic growth. Indeed, some poorer regions thanks to negative growth have actually diverged away from wealthier areas. Keywords: Oaxaca, Mexico, Beta Convergence, Sigma Convergence Thesis Mentor: _____________________ Dr. Gregory Brock Honors Director: _____________________ Dr. Steven Engel April 2015 College of Business Administration University Honors Program Georgia Southern University Acknowledgements The first person I would like to thank is my research mentor Dr.